Tucked away in the northwest of Bosnia lies a rural landscape of verdant rolling hills and golden fields of wheat. If one were to remove the minarets which pop up from behind the hills regularly, it could easily be mistaken for the Sussex downs in the south of England. The region is known as the Bihac pocket, centered as it is on the city of Bihac. The ruddy-faced workers who farm the land intensively there in preparation for a miserable winter seem jolly peasants straight from central casting. They have plenty of food, and, should they need them, medical supplies.

Their urban relatives who live on the periphery of the Bihac pocket are somewhat less fortunate. The town of Bosanska Krupa, for example, which is divided by the River Una has become the scene of permanent sniper war between the Serbs on the east bank and the Muslims on the west. The industrial district of the town of Bihac itself has been largely obliterated by Serb shells, while the road between the central town of Cazin and Bihac is too dangerous to travel. Despite this, the Bihac pocket is without question the safest Muslim-controlled region in all of Bosnia-Herzegovina. One town, Velika Kladusa, home to the giant food-processing concern Agrokomerc, has been completely spared any fighting.

At first this seems odd, since the pocket is a fat wedge some forty miles in width blocking travel between part of the Serb-controlled Krajina in Croatia to the west and the Bosnian Serb stronghold of Banja Luka to the east. But for a variety of reasons, the local Serbs, of whom ten and a half thousand out of twelve thousand quietly left Bihac in June last year, have not waged serious war against the region.

The curiously static atmosphere is hard to imagine while Sarajevo is being strangled to the south. Over Turkish coffee in the midday sun with a group of professional people, educated at Harvard, Cambridge, and the Sorbonne, a professor of philosophy came closest to a description. “Are you acquainted with the Beckett play Waiting for Godot?” he asked. “Well, he’s already been here and left, and we’re waiting to see if he comes back.” Nothing is what it seems in Bihac.

The city of Bihac is protected by hills and plateaus to the south and east. According to a senior member of the French battalion, which patrols the entire region under the auspices of the UN, the Serbs would have great difficulty keeping their supply lines open to the city if they attempted to take it. Instead they have concentrated on disabling the military potential of the Muslims in Bihac. The most spectacular example of this occurred last May when the retreating Yugoslav People’s Army blew up the complex system of underground runways of Bihac’s airport, which at a cost of $50 million was the most sophisticated military airbase in all of the former Yugoslavia.

The character and history of Bihac’s Muslim population have also had much to do with the region’s fate during the current war. “The Muslims here bear little or no relation to their cousins in Zepce or Zavidovici,” says the prime minister of Bihac, Ejub Topic, referring to towns north of Sarajevo. “We are much more Westernized and in particular more secular—religion is essentially a private matter and not a motivating ideology as it is in parts of central Bosnia.” (He was referring mainly to the rural parts of central Bosnia where religion is a more powerful influence than it is in towns like Sarajevo and Mostar.)

Living at the very tip of the Ottoman arrow which pierced the predominantly Catholic and the Eastern Orthodox regions in the Balkans, the Muslims of Bihac have become some of the most ingenious traders of Europe. Their politics have always been more flexible than those of other national groups in Bosnia and, significantly, during the Second World War, the legendary Muslim militia leader from Bihac, Hussein (Huska) Miljkovic created the so-called Huskina Krajina (Huska’s District), which was independent of both the Croat fascists, the Ustasha, and the Serb-dominated partisans. Although Huska was not always able to control his own forces, he ensured the survival of his statelet by cooperating with everybody, particularly in matters of trade.

The current war has witnessed the ghostly resurrection of the Huskina Krajina. The man largely responsible is Fikret Abdic, the Godfather of the Cazinska Krajina (to give the region its proper name). Abdic, or Babo (Father) as everyone affectionately calls him, is a remarkable personality, a brilliant fixer who has turned the Bihac pocket into one enormous black market.

Meeting him in Bihac, I found a stocky man with a square face and a cheeky smile. He doesn’t talk at all like a politician, and uses only the language of the hustler. He wants to make a deal with the Serbs and Croats because he believes it will save Muslim lives. Beside himself with anger, he denounces President Alija Izetbegovic and his allies in Sarajevo for what he says is their readiness to sacrifice Muslims in order to hold on to power: “The time for experiments is over. We must go to Geneva and participate in these tortuous negotiations. This is much more important than the issue of political positions, which is what the narrow Sarajevo circle of Bosnian potentates is fighting for. They’re not fighting for the Bosnian state, not for their people and their lives, but for their people’s deaths and for their own seats of power.”

Advertisement

He is alternately loved and hated by the Bihac Muslims. He gives a great deal, and he takes everything that he can. “He is a family man and we are his family,” says one. “He’s the only Muslim leader interested in saving lives and not losing them,” says another. “He’ll talk with the devil if there’s a buck to be made,” according to a third. “He is the devil,” says a Muslim hard-liner.

Babo first became notorious in the former Yugoslavia when the country’s largest postwar financial scandal blew up in the late summer of 1987. Abdic was director of Agrokomerc, a state-affiliated conglomerate which had become one of the country’s most successful companies, providing food to large parts of Croatia and Bosnia and employing almost all the inhabitants in the town of Velika Kladusa and its environs. Agrokomerc stood accused of issuing $1 billion in unbacked promissory notes (a fancy type of IOU) and sucking dry part of the Yugoslav banking system as he did so.

The affair rocked the Bosnian political establishment, leading to the suicide of the republic’s top political boss, Hamdija Pozderac, and Abdic spent almost two years in police custody while an investigation took place. The breakup of Yugoslavia made his release possible and he took up at Agrokomerc where he had left off. The enormous operation in buying, storing, and trading food and other items he has created since the war began has succeeded in feeding, clothing, and arming the local population, not to mention supplying it with drink.

He has persuaded the UN’s French battalion to carry oil and flour back and forth between the Bihac pocket and Croatia across Serb-held territory. The French know that he takes his cut of all transactions but they reason that he is the only man able to guarantee economic stability in the region. He negotiated the corridor with the Serbs who, of course, take their own cut. The Austrian interior ministry has issued a warrant for his arrest in connection with the misuse of over $8 million worth of funds, which Bosnian guest workers in Austria had collected for refugees in the Cazinska Krajina.

The people in Bihac were shifty when I asked them about the charges of the Austrian interior ministry. One man, however, was prepared to talk anonymously. “Fikret controls those funds because he controls everything that is used here through Agrokomerc. You have to understand that he has used that money to arm the people, to feed the people, and to keep them in contact with their families outside. Of course, he takes his 10 percent but if he didn’t none of this would happen.”

This sort of pragmatism has led to a deep division within Bosnia’s Muslim population. Abdic believes that the Muslims must negotiate their way out of the war and accept the reality of a three-way division of the country. On both sides one finds a mixture of self-interest and a genuine ideological difference. President Izetbegovic and the other leaders in Sarajevo have denounced Abdic for cooperating with the Serbs and the Croats. He has been accused of treason for breaking ranks and holding talks with the Bosnian Serb and Croat leaders, Radovan Karadzic and Mate Boban, over the territorial division of the republic. They have also attempted to undermine his control over the Bihac government by mobilizing the vocal minority of radicals in the towns, where residents tend to be much less susceptible to Abdic’s Godfather-like ways than the rural people near his stronghold of Velika Kladusa.

Abdic’s lieutenants give as good as they get. “Mr. Izetbegovic’s policy plays right into the hands of the Serbs,” says Ejub Topic, “and it will result in the physical extermination of Muslims in Bosnia.”

This division is now threatening the calm of Bihac. The man caught in the middle of the struggle between Abdic and Izetbegovic is the thirty-seven-year-old commander of the Bosnian Army’s Fifth Corps, Ramiz Drekovic. He will at some point have to decide whether he supports Abdic, who finances the army in Bihac, or the radicals in Sarajevo, who refuse to accept any carve-up of Bosnia-Herzegovina, arguing that to do so would not only reward aggression but leave them in two small “reservations,” which they compare to Bantustans in South Africa. Drekovic wears a uniform too small for him and his long and curly unkempt hair may make him seem distracted; but he is in fact an impressive military leader who has organized the chaotic farmers and tradespeople of Bihac into a disciplined and motivated force.

Advertisement

“Drekovic could go either way,” a UN official told me. “If he stays with Abdic, Bihac might come out of this unscathed although with no friends in Sarajevo. But if he moves against Abdic, this will become a very dangerous place.” With Sarajevo a badly crippled city and with Serbian and Croatian military domination established throughout most of Bosnia, the Bihac pocket may, as a result of Abdic’s wheeling and dealing, emerge as the last remaining stronghold of the Bosnian Muslims.

At the end of the Second World War, Hussein Miljkovic was murdered in predictably murky circumstances. Fikret may be corrupt and vain but so far he has saved the Cazinska Krajina almost single-handedly from destruction. In most parts of Bosnia, history has repeated itself as tragedy over the last eighteen months. In Abdic’s case, the best we can hope for is that it will end in farce.

—July 15, 1993

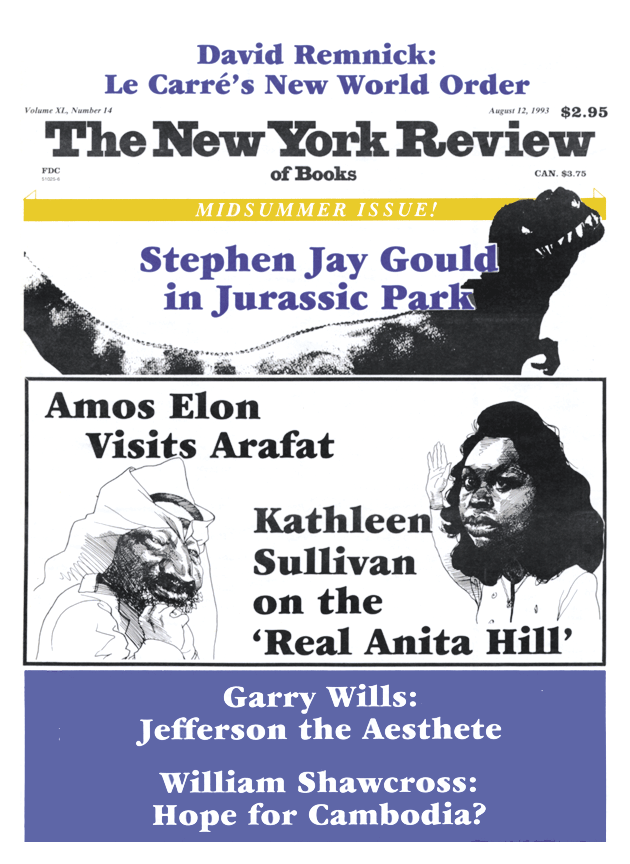

This Issue

August 12, 1993