A literary category much more common in Europe than in America depends on its unliterary charm. The author seems to take being a writer as a purely social phenomenon, without either the trouble of a sought-for vocation or the wish to make money by writing books. He writes as he might eat good food, wear good clothes, visit the right people and the right places. Sometimes a writer like Byron or Pushkin, who half despises the medium his genius compels him to work in, makes a nostalgic gesture toward the other sort of gentlemanly life he would half prefer to be living. “I hate a fellow who’s all author,” said Byron, with feeling, longing in patrician disdain to stand apart from the inky tribe.

The opposite attitude toward the literary vocation—or was it really quite the opposite?—was taken by Robert Lowell when he spoke of himself in a poem as “one life, one writing.” One suspects that what Lowell really meant was that his life was so absorbing to him—its ancestry, its relationships, its social detail—that he knew as if by instinct that it must be more important to others than anything else. The sheer confidence of Life Studies is more than regal. And it comes, in the last resort, from assumptions that royalty or aristocracy make about themselves. Or used to make. Today there is bound to be a faint air of the ancien régime about any writing of the sort one finds in Life Studies.

The same air of confidence hangs rather bewitchingly about the memoir by James Merrill, who was himself of course, with his well-to-do family, not far from the world of Robert Lowell. Lowell might himself have recognized, I suspect, the sheer ease with which Merrill’s memoir begins, the endearing lightness and self-confidence which has absolutely no need for defense or aggression, no need to explain or to apologize for itself.

Meaning to stay as long as possible, I sailed for Europe. It was March 1950. New York and most of the people I knew had begun to close in. Or to put it differently, I felt that I alone in this or that circle of friends could see no way into the next phase. Indeed, few of my friends would have noticed if the next phase had never begun: they would have gone on meeting for gossipy lunches or drinking together at the San Remo on MacDougal Street, protected from encounters they perhaps desired with other customers by the glittering moat, inches deep, of their allusive chatter. I loved this unliterary company; it allowed me to feel more serious than I was. Other friends, by getting jobs or entering graduate schools, left me feeling distinctly less so. On the bright side, I had taught for a year at Bard College, two hours by car from MacDougal Street. My first book of poems had been accepted by the first publisher I sent it to. And I had recently met the love of my life (or so I thought), who promised to join me in Europe in the early summer.

A different phase, a dedicated, literary, unsocial phase, is about to begin, but the reader already knows that it won’t go as planned. And the writer knows that the reader knows. The Jamesian charm of this opening depends on the immediacy of this relationship, so swiftly and unerringly established, as much as on what seems the wholly natural felicity of the writing. (The fact that the “glittering moat” should only be “inches deep,” where the metaphor seems to call for something much more hyperbolical, is just one instance of this unobtrusive felicity.)

And so begins Europe, and psychoanalysis, and a long affair with Claude, unagonizing and affectionate, with all the implications of that “or so I thought”; and the round of rich Americans in Rome. It is like eating a dish which has taken someone time and trouble to prepare, but whose deliciousness depends on its simplicity and lack of pretension. And the “phase” is always the same phase: “one life, one writing,” again though in a very different style from Lowell’s. The “unliterary company” too is a blessing: such a relief from the contemporary climate of literature which is solely concerned with its own possibilities in being literature.

Merrill’s memoir is in one sense as simple as a diary in which events appear to lead their own lives, as it were, and to be greeted in passing by the author’s unfailing sense of good manners. Even an acute attack of dysentery in the Greek islands is treated by the author with his usual unfailing and exquisite politeness; and the treatment given in Athens by white nuns and French-speaking doctors is described as meticulously and courteously as the beautiful little needle case given him quite casually one day by a friend who has had it since she was a child. He is never intense, never anxious: if he has any anxiety at all it seems to be the fear of boring the reader, and right from the first page we know that is not likely to happen. For one thing he is easily bored with himself, by himself; and that goes with his sunny lightness of touch, and his sense of humor.

Advertisement

So he starts dreaming about “poor plain pious Mademoiselle,” who had been his governess in his childhood, and had boarded out her own daughter in East Hampton the better to care for him. “At nine and ten, when my mother’s troubles gave her scant time for me, I transferred, day by day, more and more love to this good soul.” One day he made the mistake of telling her he loved her more than his mother, and after that nothing was quite the same again. When his parents separated “it was felt that I could do with masculine supervision.” A young Irishman was hired—“handsome as Flash Gordon”—but this was a failure. The youthful Merrill behaved so badly that the young man gave up (“and how badly in that Depression year he must have needed the job”). Through slitted eyes the author used to watch him undress, as he had with Mademoiselle, and he had often ached to lie in the arms of both of them.

The past is certainly a foreign country, as L.P. Hartley observed, where they do things differently. Merrill’s formidable mother, who came intensely to resent her son’s homosexuality, seems to have made every mistake in the book. Or don’t the upper classes ever make mistakes, by definition? Merrill is hilarious about his psychiatrists, though not exactly unkind, and they are only wheeled on for a few deft moments. The Irishman supplanted Mademoiselle, but Dr. Detre urges his patient to remember that she had originally been hired “to supplant your mother, so that she would have more time to attend to your father’s needs.” But what about his father? By seeking custody after his parents’ divorce, “hadn’t he aimed at taking my mother’s place himself?” (” ‘We’re getting warm!’ Dr. Simeons would have exclaimed; Dr. Detre let me find my own footholds.”) But wait—hadn’t he become a supplanter himself—“according to an appendix in Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary, my very name, James, meant ‘the supplanter’ “—and what about Mademoiselle’s little daughter, boarded out in East Hampton? What, come to that, about the nice young Italian police cadet, Luigi, whose fiancée he’s attempting to supplant? Such people flicker in and out of the pages with extraordinary vividness but they don’t appear for long. As for this supplanting caper, after his visits to the psychiatrist, “Reaction set in on the bus home. How deeply, how unspeakably, such perceptions bored me.”

Dr. Simeons and Dr. Detre continue to appear occasionally, like the comic couple in a film, and they are always welcome. Once the author told Dr. Simeons the following true story. After their marriage in 1925 his parents lived in a brownstone on West Eleventh Street in New York. “By autumn my mother was, as they used to say, ‘expecting’—her close friends already knew the thrilling news.” The expectation was of course of young Merrill. One day an ex-beau named Frank Huckins, who was shortly getting married himself, came to tea. As the butler showed him in Mrs. Merrill got up with deliberate awkwardness (she was only three months pregnant) and taking his hand pressed it against her stomach. The young man was aghast as “his palm sank into a deep, unnatural softness.” Smiling mischievously she removed the down pillow she’d stuffed into her dress. When Dr. Simeons heard about this “his face was a study, his laugh reluctant.” Not surprisingly perhaps: but the psychiatrists must at least have discovered that the young man had inherited his mother’s sense of humor. I’ve always wanted to write a pillow book, he told Dr. Simeons.

Dr. Detre (he lived in Rome) was especially exercised when Robert turned up. He and Merrill had become lovers (“Over meals we talked inventively, self-delightingly—no tense misunderstandings, no restful silences”). But when Robert left for home (his grandfather had died: his mother needed him) the doctor was inclined to fear that his patient had been “creating a duplicate self out of Robert.” A different person again. But was that so bad? Wouldn’t he be learning to love himself?

“No doubt. But there is only so much to gain from paying court to the mirror.”

“None of it gained by the mirror…”

“Regrettably so. It is a onesided transaction.”

When Robert left, Merrill got down to his translations of two poems by Montale. He allows us here a quick glimpse of the hard professional within. It didn’t matter that he had to look up most of the words in an Italian dictionary; the “essential failure” lay, he felt, in the realization that he was not yet a complete master of his own language. Montale, Rilke, or Neruda do a lot of accidental harm to the budding poet, he ruefully concludes, by encouraging a sort of “baby talk” in them, based on the accessibility of a user-friendly version of these great poets.

Advertisement

Auden, that more openly tough egg, would certainly have agreed. At one point in the memoir there is an inspired recollection of his talk, and the kind of things he said. Auden is introduced characteristically, on a visit to Athens. “Catching sight of me, he smiles. Although we aren’t yet the intimates we shall become after his death, he approves of my work and fancies that I exemplify moderation to Chester.” (If so, to no avail alas, for Chester Kallman continued in his undefiant good-natured way an indefatigable pursuit of evzones, the Greek kilted soldiers.) Auden meets Merrill’s friend Maria Mitsotaki—“the closest I’ll ever get to having a Muse”—and is soon expounding to her his views on the shortcomings of Latins. “They can’t be bothered to learn our language, they’ve no conception of culture, ours or theirs. I mentioned guilt in a talk I once gave in Rome, and it was translated over the earphones as gold leaf. South of the Alps guilt has only its legal or criminal sense. The rest is all bella figura.”

Arguably, and on the evidence of the Selected Poems, Auden was a better companion poet for Merrill than Robert Lowell. One cannot say more inspiring, because from his earliest volume Merrill’s verse was in its own way much too sure of itself to need such an inspiration. But he did indeed become intimate with Auden “after his death,” and the result can be seen in such a masterly poem as “The Blue Grotto,” from the 1985 collection, Late Settings. With its elegance and its dry but wholly forgiving humor the piece is pure Merrill. Everyone knows about the grotto. “That often sung impasse./Each visitor foreknew.” So how to confront the real spectacle?

But here we faced the fact.

As misty expectations

Dispersed, and wavelets thwacked

In something like impatience,

The point was to react.

The boatload react in their different ways. Don “tested the acoustics/With a paragraph from Pater.” “Jon shut his eyes—these mystics,” and thought about his mantra.

Jack

Came out with a one-liner,

While claustrophobiac

Janet fought off a minor

Anxiety attack.Then from our gnarled (his name?)

Boatman (Gennaro!) burst

Some local, vocal gem

Ten times a day rehearsed.

It put us all to shame:The astute sob, the kiss

Blown in sheer routine

Unselfconsciousness

Before one left the scene…

Years passed, and I wrote this.

The weight on the word “unselfconsciousness”; the deft and comprehensive modesty of the conclusion, and the frown of memory in the first line of the last verse which produces Gennaro’s name triumphantly in the second—these are the sorts of felicities not lightly achieved by any poet. In aggregate they produce the comprehensive grace of a long poem like The Changing Light at Sandover, or the shorter “Bronze,” which has its origin in the discovery in 1972, by a skin-diver off the Calabrian coast, of an arm thrust upward from the sandy bottom. It proved to be a Greek original, a god in bronze, but so encrusted with lime and silica that it took nine years to restore in Florence.

With characteristic acuteness Helen Vendler has observed that the “puns, ambiguities and the stanzaic shapes of English” have been used by Merrill as Matisse used the flat motifs of Muslim decorated art. The analogy sounds apposite but rather too heavyweight: Merrill’s lines are in fact as engagingly devoid of the repetitive as they are of compression or concentration. They “save themselves” as the French say, by a lightness of touch that Auden must have envied, and that is indeed one of his own special trademarks. (Incidentally Auden would have absolutely agreed with Dr. Simeons, author of Man’s Presumptuous Brain, still to be found in “holistic bookstores,” that every physical symptom—those of piles for example—is in fact psychological.)

Perhaps Merrill’s least successful verses are those which recall Lowell’s Life Studies, for Lowell etched every apparently throwaway line of those as deeply as an engraving. For Merrill, on the other hand, the significant gift of his teens was a Ouija Board. It “put me in touch with a whole further realm of language.” Messages were arresting from the start.

…born in Cologne

Dead in his 22nd year

Of cholera in Cairo, he had KNOWN

NO HAPPINESS. He once met Goethe, though.

Goethe had told him PERSEVERE.

“These lines, for all their parlor-game tone, turn out to be as crucial to my poetry as Aeschylus’s bringing on-stage an ‘answerer’…was to the development of Greek drama. Two voices—my narrative one in lower case, the young German ghost’s in upper—together compound the cozy lyric capsule. A promising start…” Certainly; and by a clear paradox a “cozy” one, but Dr. Detre did not wholly approve. Another “different person” had become involved.

The most vivid glimpse of all in this undeniably enchanting memoir is of the author’s father, “silver-haired, his round face lightly tanned, a small, compact figure in smart clothes.” Both clearly felt deep affection for each other, enhanced when traveling together in Italy by the absence of other company, beyond that of nurse and valet. Father “dreaded the company of his third wife, for love of whom he’d left my mother, and her absence from the scene added measurably to the charm of Naples and its bay. That was merely a smoking volcano in the distance, not Kinta with her whims and irascible vapors.” Kinta was to be compensated back in Southampton (“‘Don’t count on it,’ sighed my father”) by twenty identical models of her favorite shoes, made by a cobbler on Capri.

The complications of family life among the very rich are all around us, but the reader never feels excluded. The secret of this book was brilliantly summed up by Edmund White, who commented that Merrill has contrived in it “to trade in the family drama for the human comedy.” In a sense he could only do that by becoming a different person, while remaining in fact always very much himself. Nor is A Different Person in any sense a shallow book. Its “glittering moat” can safely be reckoned in fathoms, not in inches.

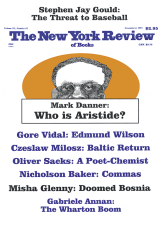

This Issue

November 4, 1993