In response to:

Misjudgment at Nuremberg from the October 7, 1993 issue

To the Editors:

It is possible to agree with most of István Deák’s criticisms of Nuremberg [“Misjudgment at Nuremberg.” NYR, October 7] without leaping to his conclusion that the effort to establish an international tribunal to try those responsible for war crimes and crimes against humanity in the wars in the former Yugoslavia “smacks of cynicism and hypocrisy.” Indeed Deák even seems to endorse the self-serving claim by Bosnian Serb leader Radovan Karadzic, a prime candidate for prosecution before such a tribunal, that its establishment “would completely destroy the UN’s credibility.”

None of the complaints that Deák makes against the Nuremberg tribunal apply to the tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. The most important criticism of Nuremberg, which was widely voiced at the time and ever since, is that it violated a fundamental principle of law by holding the defendants accountable for acts that had not been designated in advance as crimes. The charge of waging aggressive war was particularly vulnerable to this complaint. In addition, the concept of crimes against humanity was a novelty in international law, though it had certain antecedents. At Nuremberg, only the charges of war crimes—such as killing prisoners of war—clearly involved the application of established international law that was known before the crimes were committed to be binding on the parties to the conflict.

The plan for a tribunal for the former Yugoslavia that the United Nations approved on May 25, 1993 does not have that defect. The crimes that would fall within its jurisdiction are all well-established in international law. They are violations of international humanitarian law, of which the most important are the provisions of the Third and Fourth Geneva Conventions of 1949 and of Protocol I of 1977 specifying that certain acts are “grave breaches,” or war crimes. Violations of the Genocide Convention, which entered into force in 1951, are also part of the jurisdiction of the tribunal. Finally, the tribunal has the authority to try the defendants before it for crimes against humanity. Although this was a new category of crimes at Nuremberg, it has long since become accepted in international law. Indeed, despite the faults of Nuremberg, one of its great contributions was in establishing that thereafter certain crimes, when committed on a large-scale and systematic basis against particular racial, religious or political groups, would be considered crimes against humanity under international law.

Another standard complaint against Nuremberg, which Deák echoes, is that it constituted “victor’s justice.” One implication is that the tribunal could not be impartial. Again, that is not the case of the tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. None of the judges comes from a country which has been a party to the conflict. Moreover, most of the prospective defendants are leaders and officers of the victorious parties to this conflict: first and foremost the Serbs and secondly, the Croats. Putting them on trial would send a quite different message than the one that emanated from Nuremberg. Far from saying that losing a war means being put in the dock, it would say that victory does not guarantee absolution.

Another aspect of the complaint about victor’s justice is the one to which Deák devotes much of his article: that the victorious allies during World War II themselves committed many acts during the war which, under present-day international humanitarian law, would be war crimes. Deák mentions the bombing of Dresden and Hamburg, which created firestorms that killed many tens of thousands of civilians in these cities. If his article had also dealt with the war with Japan, he could have mentioned the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki as well as many other examples of attacks by the allies in which great numbers of civilians were killed indiscriminately. At least arguably, such attacks were also prohibited at the time of Nuremberg by the provision of the Fourth Hague Convention of 1907 barring the “bombardment, by whatever means, of towns, villages, dwellings or buildings which are undefended.”

Today, of course, the prohibition is unmistakable. Protocol I of 1977 provides that war crimes include: “making the civilian population or individual civilians the object of attack” and “launching an indiscriminate attack affecting the civilian population or civilian objects in the knowledge that such attack will cause excessive loss of life, injury to civilians or damage to civilian objects.” Though the allies did not stand trial for Dresden after World War II, there is no such act in this war attributable to those who will sit in judgment in connection with the crimes committed in the former Yugoslavia that should make them hesitate to judge those responsible for the indiscriminate attacks on Vukovar, Sarajevo and other communities that suffered bombardments during extended sieges.

István Deák raises the question of whether those who sat in judgment at Nuremberg were morally qualified to do so, focusing particularly on the Russians for such crimes as Katyn and the thousands of rapes and murders committed by their troops in East Europe and Germany; the French for Vichy’s alliance with the Nazis; and the United States for the period when it maintained neutrality despite Nazi aggression. Though it seems peculiar to suggest that neutrality is analogous to Katyn and mass rape, the litany of charges against the allies could no doubt be extended. To cite just one example, the French encouraged or made clear that they tolerated mass rape by Moroccan troops in Italy. Yet the legitimate questions that Deák raises about the moral competence of those who sat in judgment at Nuremberg have no relevance to the former Yugoslavia unless, here too, he considers that neutrality is disqualifying. As it happens, I am one who wished that the international community had abandoned neutrality and had intervened militarily, at least in Bosnia, to halt the carnage. Even so, when it comes to sitting in judgment of war crimes and crimes against humanity, neutrality seems an advantage rather than a disqualification.

As an alternative to an international tribunal, Deák imagines that the aggressors might “be defeated and their leaders captured” and, in that eventuality, proposes that the United Nations “encourage the newly constituted authorities in the defeated country to deal with their own war criminals.” The prospect that anything of the sort could happen is so remote—indeed, fantastic—that it does not bear comment. There are still difficult obstacles to overcome, of course, before an international tribunal takes shape. The first danger is that the international mediators, Lord Owen and Thorvald Stoltenberg, will attempt to bargain away the tribunal as part of the price for getting a peace agreement. The second is that it will be difficult to obtain custody of the defendants. Nevertheless, the proposal for a tribunal has gained sufficient momentum that it may not be easy to incorporate an amnesty, or some equivalent, in a peace treaty. Also, if the international community imposes and maintains sanctions until indicted war criminals are turned over for trial, the pressure on those harboring such persons could prove irresistible. Moreover, even if trials could not be held, indictments—especially if accompanied by detailed statements of the supporting evidence—would serve a valuable purpose. They would make it impossible for the accused to venture beyond their own borders and stigmatize them in a manner that, over time, would create great embarrassment in their own states.

Deák concludes by writing that “the lesson of the Nuremberg trials is that there should be no other trials following the model of the Nuremberg trials.” A more apt conclusion would be that what was valuable about Nuremberg need not be accompanied by what was wrong about Nuremberg. Nuremberg held the authors of great crimes accountable; individualized guilt; and, despite all its defects, helped to restore a sense of justice. The proposed tribunal for the former Yugoslavia would build on those virtues of Nuremberg. Moreover, especially because the victors would be prominent among the defendants, it would be a giant step forward from Nuremberg. And, though the specific plan approved by the United Nations Security Council on May 25 has some flaws, it avoids the faults Deák finds with Nuremberg and none of the flaws would detract from the fairness of the proceedings, the principal basis for Deák’s complaint about Nuremberg.

Aryeh Neier

New York City

István Deák replies:

Before becoming president of George Soros’s important Open Society Fund, Aryeh Neier served for many years as director of Helsinki Watch and its umbrella organization, Human Rights Watch. He is an admirable democrat and humanitarian who fights injustice and opposes cruelty wherever they are. His is a difficult job which might explain his occasional impatience and hasty judgment. I did not, for instance, draw an analogy between the US declaration of neutrality in 1939 and the Stalinist massacres at Katyn and other places during World War II. I pointed out that by not condemning Nazi aggression in 1939 and by not siding with Poland, the victim of Nazi aggression, the US violated several international agreements. This raises a question about its qualifications to sit in judgment over Nazi aggression committed in 1939. Also, much of what I said in my review of Telford Taylor’s The Anatomy of the Nuremberg Trials only summarized, in an approving way, Taylor’s analysis of the event. That my article was first and foremost a book review got somehow lost in Mr. Neier’s letter.

Admittedly, the passages on the international tribunal now being organized to try war crimes and crimes against humanity in former Yugoslavia reflected my own thoughts, and I would be distressed if my piece in any way harmed the efforts of Helsinki Watch and others in this affair. In fact, I had known next to nothing of Aryeh Neier’s and Jeri Laber’s drive to help set up the international tribunal. This exchange of letters might, at least, help awaken the interest of the public in the tribunal.

The shortcomings of the Nuremberg war crimes trial raise grave doubts, I argue in my review of Telford Taylor’s book, regarding the validity and prospects of the new international tribunal. Mr. Neier replies that important post–World War II developments in international law and the special situation in former Yugoslavia permit us to hope that something can indeed be done to apprehend, to bring to trial, and to punish the Serbian (and Croatian) mass murderers or at least to publicize their crimes.

I wish nothing more than that Mr. Neier will be proved right; but doesn’t he himself say that “it will be difficult to obtain custody of the defendants?” Difficult indeed. It is not very likely that President Milosevic, or President Tudjman, or their ministers and generals, would be arrested by some international law enforcement agency at the moment when they sign a solemn peace agreement, or address the United Nations, or pay an official visit abroad. Nor is it likely that, having wiped the state of Bosnia-Herzegovina off the map and having won United Nations approval for their misdeed, these leaders would voluntarily present themselves in court and await being sentenced, possibly to death.

Aryeh Neier mentions the possibility of another outcome: “even if trials could not be held, indictments…would serve a valuable purpose.” Aside from the doubtful legality and morality of conducting a court procedure and indicting persons without their being represented in court, one must again ask what is the purpose of it all. There is the sorry example of the 1967 Stockholm War-Crime Trial when, under the presidency of Jean-Paul Sartre, a seventeen-person jury listened to charges leveled against the United States. No testimony contradicting the predetermined conclusions was allowed, and after eight days, the tribunal solemnly declared the US guilty of war crimes in Vietnam. All this only dishonored the European left, and there is a danger that a new international indictment procedure, without defendants and without counsel for the defense, even if conducted under much more dignified conditions than that in Stockholm, would further undermine the reputation of the United Nations.

Mr. Neier is right to say that, because of the noninvolvement of the world in the massacres in Bosnia-Herzegovina, judges from countries other than Serbia and Croatia can be counted as “neutral.” Still, some of the judges already selected, for instance those from China and the United States, are likely to have different conceptions of neutrality from, say, the judge from Costa Rica. Finally, it is not impossible that the Serbian people themselves will one day be in a position to judge Milosevic and others who caused untold harm to their own nation and the region in general. The political situation in Serbia is highly volatile; a revolution might occur any time, in which case, as happened in Argentina, domestic courts could undertake to deal with the war crimes of their former leaders.

For several years now the great powers have tolerated the monstrous actions of the Serbian leaders against people who, until recently, had been their co-nationals and often their fellow Communist Party members. Moreover, the British, French, and Greek governments, if not also others, have been playing a most duplicitous role in this affair; they have, in effect, been supporting the murderers against their victims. I truly admire the heroic efforts of Helsinki Watch and other human rights organizations; but I doubt the honesty of the governments that seem likely to use the international tribunal as a face-saving measure and a substitute for action. As Mr. Neier himself points out, the tribunal is likely to be bargained away in the final settlement with the Serbian and Croatian leaders. Indeed, what else could be done if a peace treaty is arranged under the aegis of the United Nations? Mr. Neier admits that he himself used to be in favor of military intervention in Bosnia, yet he ridicules my argument that military intervention would be necessary to arrive at a decent and lasting solution. An even greater war is a very real possibility in the region because the dissolution of Bosnia-Herzegovina and the massacre and expulsion of most of its inhabitants will not solve the problem of Serbian expansionism and the conflict of diverse Balkan nationalisms. The effect of an international tribunal might be to allow the great powers to ignore this grave threat to world peace somewhat longer.

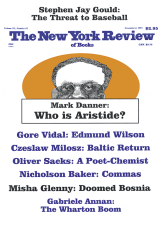

This Issue

November 4, 1993