Christopher Ricks, one of a number of English academics who abandoned Britain during the Thatcher years, is now professor of English at Boston University. He is quintessentially English, in the critical line of Johnson, Coleridge, Arnold, and Empson; an anti-theorist with eclectic tastes (Philip Larkin, Bob Dylan), and a master of the art of close reading, whose books The Force of Poetry, Milton’s Grand Style, and the hectic and illuminating Keats and Embarrassment, are of great originality. Beckett’s Dying Words is the text of his Clarendon Lectures delivered at Oxford in 1990.

The last thing one expects from critical exegeses is the pleasure of laughter. However, Professor Ricks’s study of Samuel Beckett’s last-gasp fiction, poetry, and drama is not only a superb work of criticism but also an extremely funny book. Ricks is not afraid of playing to the gallery. (“There is one thing,” he writes, “which all of Beckett’s consciousnesses are freely and unremittingly given: pause.”) The comedy is cumulative, a matter of courting danger, of sustained wordplay and delicately executed linguistic leaps, a performance that is at the very least admirable, even if one’s reaction to the more daring aerial turns may be a whispered Ouch! Reading Ricks is like watching an elegantly frenetic clown performing somersaults on a highwire. Here he is meditating on a couple of lines from one of Beckett’s late, brief prose works, The Lost Ones. The lines are: “that here all should die but with so gradual and to put it plainly so fluctuant a death as to escape the notice even of a visitor.” Ricks’s gloss is dazzling:

A triumph of mortification, the scourging word “fluctuant,” and it contrives, very oddly since you may very well never have met this exact word before, “to put it plainly.” If, lying there, you were to overhear that your pulse fluctuated, this might not mean the end; but fluctuant. And when nurses and doctors, nearests and dearests, are unnoticing, there may be the more attentive eye of the stranger. What should not escape our notice is Beckett’s penchant for locating the word “escape” in the immediate vicinity of “death.”

Death is fluctuant as birth, both necessitating contractions.

The funny moments of the book, it should be said, are incidental to Ricks’s main thesis. He is too much the pragmatic and commonsensical Englishman to attempt to erect a grand theory, yet there is a general theme, which is stated with admirable if sinuous force in the opening pages:

Most people most of the time want to live for ever. This truth is acknowledged in literature, including Beckett’s. But like many a truth, it is a half-truth, not half-true but half of the truth, as is the truth of a proverb. For, after all, most people some of the time, and some people most of the time, do not want to live for ever.

Quoting Eliot’s well-known dictum that poetry “is not the expression of personality, but an escape from personality,” Ricks goes on to claim that for Beckett, “last-trumping even the escape from personality and emotions, and constituting the only entire escape from them, must be the escape from consciousness, and in particular the guaranteed form of this, the escape into death.” It is, then, the yearning toward death that Ricks sees as a—perhaps the—central concern of Beckett, the underground river coursing through the depths of all his work, that same stream flowing in Philip Larkin’s line that Ricks quotes: “Beneath it all, desire of oblivion runs.”

In pursuing his argument Professor Ricks follows the curve of Beckett’s work from the mordant gaiety of the early novel Murphy, in which the eponymous antihero ends up bound by scarves to his rocking chair and “dying burnt to bits,” through the robotic somnambulism of Watt and the decrepitudes of Molloy, Moran, and Malone of the Trilogy, to the compressed, heartbreaking, magnificent late texts such as Company and Ill Seen Ill Said—last things, indeed.

The urge toward death is to be found everywhere in Beckett and is most beautifully expressed in his prose fragment From an Abandoned Work:

How often have I said, in my life, before some new awful thing, It is the end, and it was not the end, and yet the end cannot be far off now, I shall fall as I go along and stay down or curl up for the night as usual among the rocks and before morning be gone. Oh I know I too shall cease and be as when I was not yet, only all over instead of in store, that makes me happy, often now my murmur falters and dies and I weep for happiness as I go along and for love of this old earth that has carried me so long and whose uncomplainingness will soon be mine. Just under the surface I shall be, all together at first, then separate and drift, through all the earth, and perhaps in the end through a cliff into the sea, something of me.1

Yet Ricks’s reading of Beckett, close though it may be, is, I believe, itself a half truth, “not half-true but half of the truth.” For Ricks “death” means physical extinction, whereas in Beckett’s writings it is something at once more complex and less final, a state of being–beyond, of extension into a netherworld below the lip of language, a place or state of grace (as the old Catechism used to describe Limbo) where the souls of the departed linger, talking to themselves. At the end of the Trilogy’s second volume, Malone Dies, Malone does indeed die in faltering and ever-diminishing steps:

Advertisement

never there he will never

never anything

there

any more2

but immediately the Molloy/Moran/Malone voice starts up again: “Where now? Who now? When now? Unquestioning. I, say I.”3 In Beckett the yearning is always toward not for death; a kind of infinitesimal calculus is at work whereby the life of the characters approaches nearer and nearer to extinction yet never quite disappears into the final black hole.

Ricks is rightly contemptuous of such postmodernist critics as John Pilling and Victor Sage who see Beckett’s work as no more than a series of language games utterly detached from reality—or “reality,” as the post-modernists like to frame it (Ricks: “the usual treatment, the infected hygiene, iatrogenic, of inverted commas…”). Yet I believe that in his conviction that Beckett’s theme is humankind’s desire to “escape from consciousness…escape into death,” Ricks misses, or chooses to miss, the point that Beckett’s narrators make over and over again: that their prime concern is not the death of the organism but the life-in-death of the word, the collapse into silence that always threatens but never quite occurs. As the voice in From an Abandoned Work neatly puts it,

Over, over, there is a soft place in my heart for all that is over, no, for the being over, I love the word, words have been my only loves, not many.

A large number of the fictions, and almost all of them from The Unnamable onward, seem to be uttered by voices from beyond the grave. Even as early as the short story “The End” from the late 1940s death seems already to have occurred, from the ambiguous layingout of its opening (“They clothed me and gave me money. I knew what the money was for, it was to get me started.”) to the book’s close aboard the old boat that might once have been Charon’s, when

now in the stern-sheets, my legs stretched out, my back well propped against the sack stuffed with grass I used as a cushion, I swallowed my calmative. The sea, the sky, the mountains and the islands closed in and crushed me in a mighty systole, then scattered to the uttermost confines of space. The memory came faint and cold of the story I might have told, a story in the likeness of my life. I mean without the courage to end or the strength to go on.4

In works such as the late, Dante-esque piece The Lost Ones and the novel How It Is, the action, what there is of it, takes place in a netherworld far below even that semi-comatose state that Beckett’s nay-sayers call life. And yet, miraculously, these works, “posthumous” in their own, special sense, speak to and of us, the living, in ways that are immediate, poignant, and familiar. Beckett is that Spinozan wise man who thinks constantly of death yet whose thinking is always a meditation on life.

But “life” in this sense is bestowed on the living by language and only by language; words are Beckett’s life-support system; where there is speech there is life (as The Unnamable has it: “It will be I, it will be the silence, where I am, I don’t know. I’ll never know, in the silence you don’t know, you must go on, I can’t go on, I’ll go on”). The essential drama of Beckett’s writing derives from the spectacle of a literary artist putting his head into the lion’s mouth of silence again and again and always surviving, just about. After the collapse into incoherence at the close of Malone Dies (1956) no advance seems possible, yet when we contemplate the writer’s career we realize that this was only the halfway point of his middle period. Still to come were The Unnamable, How It Is, Godot, and Endgame, and the great late works—his final prose piece was called Stirrings Still. Beckett’s heroic venture along the darkling border between language and silence has more relevance to our everyday lives than most of the thick tomes of “realistic” (the hygiene of inverted commas is justified here, I think) fiction this century has produced. As Adorno says:

Advertisement

The unresolved antagonisms of reality reappear in art in the guise of immanent problems of artistic form. This, and not the deliberate injection of objective moments or social content, defines art’s relation to society.5

I do not say that Professor Ricks is unaware of these aspects of Beckett’s achievement, nor do I think he would greatly disagree with the emphasis I am placing on them here. The strength and the pleasure of Ricks’s style lie in its quickness, the lightness and sureness of its touch. The book is commodious in its brevity by virtue of a linguistic athleticism which in places approaches the mastery it celebrates in the work of its subject. I do not know of any living critic who can combine obsessively close reading with such gaiety and intricacy of expression. Perhaps in places the prose does become self-indulgent, even self-dramatizing (“This intimated darkly the depths of death’s oblivion,”) but the sustained linguistic brilliance and playful solemnity of tone contribute to the creation of a perfect medium with which to scrutinize Beckett’s grave illuminations and humor.

Ricks’s book consists of four sections, “Death,” “Words that Went Dead,” “Languages, Both Dead and Living,” and “The Irish Bull”; there is also a short postscript in the form of an obituary written a year after Beckett’s death in December 1989. Ricks allows his argument to wander far and wide yet always he maintains a kind of rackety consistency. In his quest for real-life examples to set beside Beckett’s thanatological ambiguities he trawls through a large selection of Books of the Dead, with lively results. (My favorites are this, from James Steven Curl’s study of funerary architecture, A Celebration of Death: “Golders Green…is one of the most architecturally successful of all crematoria in Britain…built of a warm red brick,” and this, culled by Ricks from a London Times obituary: “At his death he was at work on his final thesis on the metaphysical significance of death.”)

Ricks also turns up from his wide reading many surprising and surprisingly apt prefigurings and echoes of Beckett’s morbid sprightliness, from sources as various as Spenser and Philip Larkin, Samuel Butler and Robert Lowell (“All’s well that ends”), Swift and Housman (“the lover of the grave, the lover/That hanged himself for love”).

Ricks is not really out to prove a preordained case of his own; on the contrary, he sticks always to the case in hand. He is before anything else a reader, and reading—by which I mean that self-forgetting, passionate scrutiny to which a great critic subjects the text—is the finest service he can perform, both for Beckett and for Beckett’s readers. His aim is to make the text resound, and re-sound, so that we shall hear it anew in its multi-tonal sonorousness. Here he is, unpicking the tight-packed chords of a couple of lines of Beckett’s verses after Chamfort:

Better on your arse than on your feet,

Flat on your back than either, dead than the lot.There “feet,” at the end of the first line, rounds at once, in sound and sense, on “Flat” at the start of the next; “feet” and “Flat” find themselves back to back, corporeally absurd, and compounded by the prompt apt “Flat on your back.” Clinched, finally, with “dead than the lot,” where the upshot is not only the whole kit and boodle but a humbling of the grander sense of the human lot.

This is dense commentary, yes, but not, I would insist, obscure.

And the humor? Ricks finds it in the unlikeliest places: in Beckett’s use of parentheses, for example. In the section “Words that Went Dead” he dwells on a passage from the early novel Mercier and Camier, which recounts with farcical solemnity the adventures of a lugubrious pair of friends who owe much to Flaubert’s Bouvard and Pecuchet, not to mention Laurel and Hardy, and prefigure Waiting for Godot’s doubled pairs of Didi/Gogo and Pozzo/Lucky:

With the hand that held the truncheon he drew a whistle from his pocket, for he was no less dexterous than powerful. But he had reckoned without Mercier (who can blame him?) and to his undoing, for Mercier raised his right foot (who could have foreseen it?) and launched it clumsily but with force among the testicles (to call a spade a spade) of the adversary (impossible to miss them).

On which Ricks comments with characteristic frolicsomeness: “Not to beat about the bush, these suspensions ( ) are notably scrotal.”

Beckett’s Dying Words is a wonderfully invigorating reading of a body of work too often regarded as bleak, pessimistic, life-denying. Ricks shows us where the seriously funny jokes are buried like truffles amid the rich loam of Beckett’s language. True, his book very nearly runs out of steam (or breath) in the penultimate section, a long and aimless gallop on the Irish bull (“A blunder, or inadvertent contradiction of terms, for which the Irish are proverbial”—Brewer) which no doubt was wonderful to listen to in the lecture hall but which could with profit have been dropped from the book or at least compressed.

Much can be forgiven Ricks, however, for the range and depth of his achievement. Beckett’s Dying Words is quick with life. He has read himself deep down into the texts to those places from which the laughter and the sorrows rise. As Belacqua, the main character of Belacqua, the main character of Beckett’s novel Dream of Fair to Middling Women, puts it, with characteristic ponderousness, “But in the umbra, the tunnel, when the mind went wombtomb, then it was real thought and real living.”

Ricks lifts this quotation from a critical study by Lawrence Harvey, itself based on the manuscript version of Dream of Fair to Middling Women. As the schoolboy humor of the title, making not very clever play with Chaucer, would suggest, Dream was Beckett’s first novel. It was written in Paris in the summer of 1932 when the author was twenty-six and is published now for the first time. When he had finished the book Beckett submitted it to a number of London publishers (including, he writes, “Shatton and Windup” and “The Hogarth Private Lunatic Asylum”), without success, unsurprisingly. (There would of course have been scant hope of publication in Ireland, censorship laws being what they were in those early years of what was known, inaptly, as the Free State.)6 He then put away this “chest into which I threw my wild thoughts,” but not before he had cannibalized it for material for the volume of short stories, More Pricks than Kicks, which was published in 1934. In 1961 Beckett gave the typescript to Lawrence Harvey, to assist him in the writing of his monograph, Samuel Beckett: Poet and Critic. In 1971 Harvey gave the manuscript, presumably with Beckett’s permission, to Dartmouth College, New Hampshire, where it remained until Beckett’s death.

All this is recounted in the foreword by Eoin O’Brien, one of the two editors (the other is Beckett’s friend Edith Fournier). In the 1970s when O’Brien was working on his fine photographic study, The Beckett Country,7 he “realised how deficient a book purporting to illustrate the origins of much of Samuel Beckett’s writing would be if Dream…was not referred to.” Shortly before his death Beckett told O’Brien that he wished Dream to be published, “but he did not want this to happen until he was gone ‘some little time.’ He asked me to hold the ‘key’ to the ‘chest’ until I thought fit.” Last year O’Brien’s Black Cat Press, amid some controversy, brought out an edition which was available only in Ireland; Arcade’s is the first international edition.

Eoin O’Brien, for whom I have the highest respect, describes Dream as “a major literary achievement”; I cannot fully agree. But we owe a debt of gratitude to O’Brien and Fournier (and to Beckett’s literary executor, Jérôme Lindon, and his longtime English publisher, John Calder) for making Dream available to readers scholarly and otherwise. The book is a fascinating document, wherein most of the themes and obsessions of Beckett’s later work are to be found in embryonic form. Whether it is a “major achievement” is another matter.

Certainly Dream could not have been written by anyone other than Beckett. That inimitable—or, rather, all too imitable—voice is there from the first lines: “Behold Belacqua an overfed child pedaling, faster and faster, his mouth ajar and his nostrils dilated, down a frieze of hawthorn after Findlater’s van, faster and faster till he cruise alongside of the hoss, the black fat wet rump of the hoss.” Even the quirkily rhythmic punctuation is prophetic of the mature Beckett. The story, if such it can be called, concerns the adventures of Belacqua, who like all young men is having Trouble with Girls, in his case the quaintly named Smeraldina-Rima and the Alba (both are preceded by the definite article, who knows why); there is also much toing and froing between Ireland and the Continent and, of course, Rows with Parents (in a moving and unexpectedly tender passage Belacqua carries home from France the gift of a bottle of perfume for his mother).

This is, indeed, a young man’s book. If I had not been told Beckett was in his twenties when he wrote it I would have said it was the product of an extraordinarily clever, over-educated eighteen-year-old with a tendency to melancholia and a gift for languages. There is much preciousness and striking of poses, and of course, since this was 1932, there is the obligatory impenetrable passage written in the manner of Finnegans Wake, or Work in Progress as it then was. Beckett, who at the time hero-worshiped Joyce, wrote a fine essay on the master’s last great work.

As Dream shows, Beckett took a long time to grow up as a writer. Some critics would hold that it was really not until 1945, with the completion of the extraordinary novel Watt, that the true Beckett voice was heard, even though he had already completed Dream, More Pricks than Kicks, and the dourly comic novel Murphy (about which Joyce wrote a scathing limerick that wounded the young Beckett deeply). It is always dangerous to read too directly from the life to the work of any artist, but it does seem that Beckett’s experiences during the Occupation in France, where he spent the war partly on the run from the Gestapo (he had done some work for the Resistance, which he characteristically dismissed as “schoolboy stuff”), had a profound effect on his writing. Thereafter in his art he had to find a way to “allow in the chaos,” and it is indeed his great achievement to have fixed our terrible century in works in which the light is more luminous for darkness’s inextinguishable presence.

For the Beckett enthusiast, Dream is an indispensable text; for new readers, however, or those renewing their acquaintance with one of the great figures of twentieth-century literature, this chest is likely to seem stuffed too full with dubious treasures.

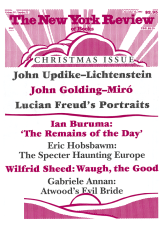

This Issue

December 16, 1993

-

1

Collected Shorter Prose 1945–1980 (John Calder, 1984), pp. 133–134.

↩ -

2

Molloy, Malone Dies, The Unnamable, one volume (Grove, 1958), p. 289.

↩ -

3

Molloy, Malone Dies, The Unnamable, p. 293.

↩ -

4

Collected Shorter Prose 1945–1980, pp. 51 and 69–70.

↩ -

5

Theodor Adorno, Aesthetic Theory (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1984), p.8.

↩ -

6

See Beckett’s essay “Censorship in the Saorstat,” in Disjecta, edited by Ruby Cohn (London: John Calder, 1983).

↩ -

7

Black Cat Press/Faber, 1986.

↩