Ars est celare artem, according to the Latin proverb—art lies in the concealment of art. It ain’t necessarily so; but after reading through The Oxford Book of Comic Verse one is certainly forced to the conclusion that the finest comic effects, put into meter, are deadpan, not apparently aware of themselves as comic. This may happen in two ways. In the eighteenth century wit was the thing, rather than what was merely “comick,” and verse reflects this in the taut and dazzling couplets of Pope and Swift, which we are to admire as performance rather than indulge in any sort of mirth, let alone a horse laugh. One of the best and rarest specimens John Gross provides is an extract from Matthew Green’s The Spleen.

Sometimes I dress, with women sit,

And chat away the gloomy fit;

Quit the stiff garb of serious sense

And wear a gay impertinence…

Talk of unusual swell of waist

In maid of honour loosely laced,

And beauty borrowing Spanish red,

And loving pair with separate bed,

And jewels pawned for loss of game,

And then redeemed by loss of fame…

And thus in modish manner we

In aid of sugar, sweeten tea.

Green, who died in 1737 aged forty-one, no doubt suffered from the spleen, and found wit and gossip among women a relief from it, as many others have done. No doubt it was also a relief to compose quick bright verses in celebration of such occasions.

The second way of not horsing about in comic verse and thus inviting the sort of laughter that clowns get—a deplorable habit with nineteenth-century poetasters like Thomas Hood, and even, on an off day, the great W.S. Gilbert himself—is to give not the slightest indication that the lines you are writing are intended to be funny. A.E. Housman, classical scholar and author of A Shropshire Lad, was very good at this. He once woke up dreaming that he had written some melancholy little verses that began:

When I was born into a world of sin

Praise be to God it was raining gin.

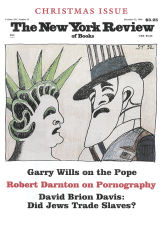

His parodic “Fragment of a Greek Tragedy” is just as straight-faced, and so is the “Fragment of an English Opera,” which John Gross finds room for here, together with Housman’s lines on the Pope.

It is a fearful thing to be The Pope.

That cross will not be laid on me, I hope.

Not only does the intention to be “comical” seem absent with this poet, but there is a kind of grave absent-mindedness about the business. His real work is elsewhere. Had Einstein the gift of language he might have written little bits on relativity in the same vein, for the comic in this deadpan sense makes no attempt to mock, or to poke fun at serious matters, but complements and completes them. It is a fearful thing to be the Pope, no doubt, and Housman’s way of drawing attention to the fact makes us see it in a new light: personal relief mixed with just a little anxiety in case it should actually happen.

The comic in verse depends, and sometimes too much, on the zany felicities or infelicities of rhymes. Gross might have included almost any stanza from Byron’s Don Juan, but Byron’s rhymes love to draw deliberate attention to themselves, part of their overall pose and swagger, whereas the best comic rhymes seem an accident which produces the unexpected and the unforeseen. What ever caused them to see the light? Gelett Burgess (1866–1951), author of “The Purple Cow,” obviously had no idea.

Trapping fairies in West Virginia:

I think I never saw fairies skinnier.

And that’s it. Part of the comic point is its own inadequacy, which the rhyme manages to couple effectively with the surreal, so that the outcome is a kind of grave, surprised sobriety with a repressed giggle in it. Edward Lear knew the formula and overdid it, which is why his better limericks quoted here are not his “best,” that is the most Lear-like and well-known: these are what everyone knows such an anthology wisely avoids, for nothing destroys the comic in verse more than notoriety: a well-known verse joke ceases to be a joke and becomes a bore. Humor in prose may stand repetition, but the comic in verse must be a glorious surprise; and imprisoned as it is in its own felicitousness it can only do that the first time. The Cabots and the Lowells, Mabel and the martinis, Stevie Smith not waving but drowning, and Elinor Glyn on the tiger skin, become with time, alas, worse than a yawn: they become an embarrassment. They were, literally, too good to last.

This is a good anthology because it seems tacitly to understand the point; and although it has had to include some too famous items for the sake of appearances, its choicest items are rarer and more obscure. Having avoided satire the editor nevertheless tells us in his brief introduction that he would like to have put in more Pope, such as the account of the merchant Balaam in the Moral Essays. But, he justly says, the piece changes course in mid-poem, and in place of the comic we find ourselves confronted with pure venom. The merchant is comfortably ridiculous, but his daughter pays the penalty for social climbing and for marrying a dissolute viscount—“She bears a Coronet and Pox for life”—and we must agree with Gross’s judgment when he says that “in the end I just couldn’t find a place in an anthology of comic verse for that.” G.K. Chesterton’s digs at grocers or atheists come out, on the other hand, unexpectedly well, for they manage to combine absurdity with sunny good nature: there seems no more private bile in them than overt desire to be brilliant, and to show off. I like his quatrain on Middleton Murry’s pompous farewell to the deity in a book Murry simply called God.

Advertisement

Murry, on finding le Bon Dieu

Chose difficile à croire

Illogically said “Adieu,”

But God said “Au Revoir.”

But why is it, I wonder, that modern comic verse writing is not usually very successful when compared to the Victorians, to whose poets it came by nature and who did it with a natural zest. Is modern poetry too self-conscious to gambol with any degree of happy spontaneity? There are wonderful exceptions like John Betjeman and sometimes Philip Larkin, who are, as it were, Victorian by nature, and who combine a modern topic with the most careful old-fashioned craftsmanship. Free verse rarely goes with the comic effect: rhyme is all but essential to it.

M is for Marx

and Movement of Masses

and Massing of Arses

and Clashing of Classes.

That little gem is by Cyril Connolly, and is as comic in its own way as the thought of trapping fairies in West Virginia. Both reach the absolute of incongruity without apparently trying. On the other hand Richard Usborne’s “Epitaph on a Party Girl,” excellent as it is, clearly took a lot of time, effort, and careful ingenuity, of the sort that a graveyard poet in any era might have expended.

Lovely Pamela, who found

One sure way to get around

Goes to bed beneath this stone

Early, sober, and alone.

But it has no character in the sense that C.S. Calverley had his own in the 1840s and 1850s, and Larkin, Betjeman, and Ogden Nash have had theirs in our time. It was probably no trouble to T.S. Eliot to write old-style comic verse about cats, for which he has become more widely famous than for his real poetry, and yet to be an original comic poet is probably as rare and as difficult as it is to be a serious one. This admirable anthology shows us how that can be, and gives many fine and little-known examples of little-known poets who have succeeded, including, naturally, Mr. and Mrs. Anon.

Of course it might be argued that good serious poetry is in its own way comic, and vice versa. John Betjeman, like Edward Lear, is continuously both romantic and funny—a very rare combination—though there is about him none of the professional comic poet, which is also a rare and in our time all but obsolete species. Sir Max Beerbohm was not romantic and funny, but he was demure and funny, a combination which at its best can be equally exhilarating. Many of his verses have dated a little together with their subjects, but the wonderful poem called “A Luncheon” takes off from Thomas Hardy in the same way that Betjeman’s memorable verses take their inspiration from Hardy’s Mellstock choir. So good is it, and so briefly subtle, that it should be quoted as a whole.

Lift latch, step in, be welcome, Sir,

Albeit to see you I’m unglad

And your face is fraught with a deathly shyness

Bleaching what pink it may have had.

Come in, come in, Your Royal Highness.Beautiful weather?—Sir, that’s true,

Though the farmers are casting rueful looks

At tilth’s and pasture’s dearth of spryness.—

Yes, Sir, I’ve written several books.—

A little more chicken, Your Royal Highness?Lift latch, step out, your car is there,

To bear you hence from this antient vale.

We are both of us aged by our strange brief nighness

But each of us lives to tell the tale.

Farewell, farewell, Your Royal Highness.

Like all good imitations, it not only loves its original but is uplifted by it; in this case to a higher art of poetry than Beerbohm was usually able to manage, for all his verbal and pictorial skills. The resemblance to Hardy’s own musing tone and rustical-comic ironies is uncanny—“unglad” is a stroke of genius—and with Beerbohm’s usual delicacy the resemblance is exaggerated just enough to bring out the odd comedy of a real event. It was a visit in the summer of 1923 by the Prince of Wales, later and after his abdication the Duke of Windsor, who lunched with the Hardys on his way down to Cornwall. When Mrs. Hardy discreetly inquired what the Prince would like to eat, his secretary cabled back “chicken and whisky.” Half way through lunch the Prince retired to take off his waistcoat, chucking it at his valet with the words “It’s too damned hot! You wear the bloody thing yourself.” One hopes the poet heard this little exchange. Beerbohm catches the oddity there must have been in the brief encounter between two such very different persons and converts it into absolutely deadpan monologue, part interior, part what Hardy himself might actually have said. The result is unique, and one of the funniest things that Beerbohm ever wrote.

Advertisement

I owe the details about the luncheon party to the learned and meticulous notes of the editor, J. G. Riewald, who has performed a magnificent service in bringing together here all Beerbohm’s verses, nowhere else available as a whole, and copiously annotating them in an edition whose elegance would have satisfied the exacting standards of Beerbohm himself. I used to hear stories about Beerbohm’s kindness and friendliness of manner from my old teacher Lord David Cecil, who had been a great friend. The only time I encountered the great man himself was when he came to school to give a lecture, early on in the war. His talk was the most finished and charming performance imaginable, and in the course of it he told a story from his own schooldays about a boy who was put on to translate a line of Euripides in class, and came up hesitantly with the rendering “And a tear shall lead the blind man.” “Clever tear,” observed the schoolmaster wearily; but the youthful Max was struck by the strange poetry of the mistranslation, and when he afterward discovered what seemed to him similar effects in W. B. Yeats’s poetry, he composed, he told us, “a little piece of Yeats himself.”

From the lone hills where Fergus strays

Down the long vales of Coonahan

Comes a white wind through the unquiet ways,

And a tear shall lead the blind man.

Max’s parodic genius was equally at home with the poets of the fin de siècle, especially the one he had invented himself—the immortal Enoch Soames of Seven Men, perhaps its author’s most sustained feat in a genre he invented himself: the tale which is part parody, part exquisitely humorous sketch, and part psychological study. So acutely drawn are these perceptive portraits—A. V. Laider the fantasist, James Pethel the early motorist gambling with his own life and those of his passengers, Enoch Soames the failed poet who sold his soul to the devil for a glimpse of possible future fame—that they come to us as almost more real in Max’s prose than do his accounts of his own actual contemporaries. No doubt the sketches were based on men he had met, but they appear before us with a vividness only to be achieved by consummate art. They are, as it were, parodies come to life, in the way that Enoch Soames lives in the different styles of Nineties verse that he practices.

Lean near to life. Lean very near

—nearer.

Life is web, and therein nor warp nor woof is, but web only.

That is Soames essaying to write as a “Catholic Diabolist,” but in his second collection, Fungoids, he showed himself to be equally at home when celebrating a young woman so decadent she was almost nonexistent, or performing a rollicking nocturne with the Devil. Max also enjoyed a sly dig at a genuine contemporary, like George Moore, who was forever hinting at his female conquests.

That she adored me as the most Adorable of males

I think I may securely boast. Dead women tell no tales.

It is said that his knighthood was delayed for thirty years when his “Ballade Tragique” on the ennui of court life, with its refrains by a desparing male and female courtier—“The King is duller than the Queen,” and “The Queen is duller than the King”—was brought to the attention of Their Majesties King George and Queen Mary. “Kind friends sent it to them,” remarked its author dryly.

Max was no innovator. He seems indeed to have reveled in employing the stalest old verse fashions of his youth—triolet, limerick, and simpering ballad—but he gave them a new sort of life and bite, and he did the same for the almost equally venerable form of the Christmas annual or collection. A Christmas Garland woven by Max Beerbohm assembles a collection of little essays on the theme of Christmas, not the ordinary little light jeux d’esprit favored by newspapers and periodicals at the time but brilliant imitations of the writers with whom all well-read members of the public were then familiar. “Imitations” is of course all too inadequate a word; again—and as in his verses—his peculiar genius breaks out in flights of fancy that seem to extend the range of the talented author they are understudying.

Conrad was particularly flattered by the ironic little tale called “The Feast” that Max served up in his honor, remarking that he not only felt famous all of a sudden but that he had the sensation of reading himself at his best, “or even better.” Not all the authors Max parodied were possibly equally gratified by his attentions: Henry James was apparently not so much put out as perturbed by “The Mote in the Middle Distance,” in which two grave Jamesian infants ponder together the contents of their Christmas stockings. Did he really waste quite so much time and space in quite this way?

One or two of the pieces, for example that on the now forgotten historical novelist Maurice Hewlett, on G. S. Street, even on John Galsworthy, have necessarily less impact today than they must once have had. Even so there are things in all of them so felicitous that the reader chuckles without quite knowing what the grounds for amusement are, or originally were. One of the funniest is on A. C. Benson, in his time the doyen of “third leader” writers, an almost unconscious master of the amiable vacuities which in their time beguiled the middle-class breakfast table.

More and more, as the tranquil years went by, Percy found himself able to draw a quiet satisfaction from the regularity, the even sureness, with which, in every year, one season succeeded to another. In boyhood he had felt always a little sad at the approach of autumn…. Once, when he was fourteen or fifteen years old, he had overheard a friend of the family say to his father “How the days are drawing in!”—a remark which set him thinking deeply, with an almost morbid abandonment to gloom, for quite a long time. He had not then grasped the truth that in exactly the proposition in which the days draw in they will, in the fullness of time, draw out. That was a lesson that he mastered in later years.

The word “mastered” is almost as felicitous in its context as is “unglad” in the Hardy poem, and the full fatuity of poor Benson is so brilliantly caught that one can feel oneself insensibly lapsing into a state of mindless contentment, under the caress of the syllables. Benson’s writing was above all supremely harmless, a quality, as N. John Hall points out in a long and superb introduction, which Max neatly catches in the piece’s title, “Out of Harm’s Way.” As J. G. Riewald’s notation is the perfect commentary and companion to the Beerbohm verses, so Hall’s scholarly but unemphatic learning in the byways of the Edwardian literary scene leads us into this world which Max understood so well, and portrayed with such affably feline precision.

Yet that precision is purely creative: it never belittles what it touches, even when Max is suggesting that Kipling’s admiration for the “manliness” of men shows that he was really a lady novelist in disguise! No wonder James read the book “with wonder and delight,” and even claimed to feel ruefully from then on that he was “parodying himself.” But Max really did hate Kipling, and everything he seemed to stand for, and Kipling himself could only have winced at the parody, as he must have done at the marvelous cartoon of the irately mustached little comic demon, with a stately blonde on his arm who is wearing his bowler hat. The caption goes “Mr Rudyard Kipling takes a bloomin’ day aht, on the blasted ‘eath, along with Britannia, ‘is gurl.” (Interesting by the way that we all say “gurl” now, as cockneys are said to have done: better-class Edwardians said “gel” or “gal.”) What must poor A. C. Benson, himself, and rather significantly, a melancholy depressive, have thought of the placid sentences of “Out of Harm’s Way,” or the cartoon that represented “Mr Arthur Christopher Benson vowing eternal fidelity to the obvious”? That cartoon itself has apparently disappeared—perhaps Benson bought and destroyed it?

It is impossible to convey in a review the riches that lie “embedded and enjellied” (as Tennyson sang of the best veal and ham pies) in the admirable Beerbohm collections, and in the Comic Verse anthology too. One would like to think of Max himself pondering, with the appreciation of a connoisseur, those inimitable lines of Gelett Burgess about trapping fairies in West Virginia; and probably working out for himself (since he knew little of America although he was in his later years married to an American lady) the significance of fairies being skinnier in West Virginia than they would be elsewhere, while savoring the leisurely twang in the trapper’s ruminative couplet. An artist like Max would recognize a fellow artist at any distance. Tripping gravely through the ebullience of his own and others’ fancies was the chief occupation of a man upon whom Oscar Wilde said the gods had been generous enough to confer the gift of perpetual old age.

This Issue

December 22, 1994