In response to:

The Revenge of the Repressed: Part II from the December 1, 1994 issue

To the Editors:

We were distressed to find The Courage to Heal trashed in Frederick Crews’ review “The Revenge of the Repressed” [NYR, December 1, 1994]. Crews’ article was rife with inaccuracies, only a few of which we will address here.

1.) Crews says The Courage to Heal is not about “surmounting one’s tragic girlhood” but about remaining an embittered victim. This is absolutely false and it is beyond our imagination how anyone who has ever so much as skimmed The Courage to Heal could come to that conclusion. The Courage to Heal is a compassionate, forthright book about healing, reclaiming one’s life, and ultimately, moving on.

2.) We never have said, nor do we believe, that “repressed abuse is more pervasive than remembered abuse.” Contrary to Crews’ representation, our book is not primarily about memory. Its six hundred pages cover a wide range of topics of relevance to survivors: self-esteem, sexuality, trusting yourself, parenting, relationships, intimacy, feelings, grief and family issues.

3.) Although we are feminists and proud of it, we have no idea what Crews is talking about when he says our book is based on reports of sexual abuse reported in “women’s collectives.” What women’s collectives is he referring to?

4.) There is nothing anti-male in The Courage to Heal. We certainly do not believe, and have never put forth the idea that “all men are rapists at heart.” The problem of child sexual abuse transcends gender. We discuss abuse by women, men who support women’s healing, and are further gratified that our book has been helpful to so many male survivors.

5.) It is ignorant to ridicule non-physical sexual abuse. If an adult forces a small child to watch pornographic films, but never lays a hand on her, it is sufficient to inflict grievous harm on that child.

6.) Crews says that our knowledge base comes from women who’d always remembered their sexual abuse. This is not true. The survivors we interviewed for The Courage to Heal represented a broad range of experiences. Some had always remembered their abuse. Some remembered portions, but not all of their experiences. And those who did recover memories in later life rarely did so in the context of therapy or a support group, as Crews erroneously states.

7.) And lastly, we are not “nervous” about damage suits. Both of the suits filed against us in the past year were immediately thrown out of court. Nor are we “nervous” about the backlash. We are, however, seriously concerned about the effect it is having on survivors and on child victims today. Survivors who are coming forward today to talk about their experiences are facing a climate of disbelief and disdain, in large part due to attitudes like the one expressed in your article.

Although we believe there is—and should be—room for debate and honest differences of opinion in what has become a fierce media battle over recovered memories, Crews’ article unfortunately presents nothing but more of the same nastiness and mean-spiritedness which has characterized so many backlash articles.

One cannot help but wonder what would motivate someone to insult, misrepresent, and ridicule everything about The Courage to Heal in the name of a book review, rather than point out both the strengths and weaknesses of the book. Isn’t that what book reviews are for?

Despite Mr. Crews’ rather jaundiced opinion, The Courage to Heal has helped hundreds of thousands of survivors deal with the past and establish healthy, satisfying lives. Crews fails to pay even lip service to the good our book has done. By filling his review with misinformation and taking such a vitriolic stance, he undermines his own credibility and does a disservice to your readers.

Ellen Bass

Laura Davis

Co-authors, The Courage to Heal

Santa Cruz, California

Frederick Crews replies:

In their letter, Ellen Bass and Laura Davis present themselves as innocents who are unaware of any social damage caused by The Courage to Heal. Their chapters, after all, consist mostly of tender advice and instructive stories and testimonials, all designed to comfort and guide victims of sexual molestation. Where, they want to know, is the harm in that?

The catch is that, by and large, the “Survivors” to whom their book makes its strongest appeal are not women who have always remembered early sexual abuse. Most such women have long since forged their individual strategies for coping with painful memories and emotional wounds. By contrast, those who desperately cling to Bass and Davis’s counsel are struggling to convince themselves or to stay convinced, in opposition to everything they have previously believed or recalled, that they were chronically raped in childhood, usually by their fathers and/or other related males. The active core of The Courage to Heal is precisely its “supportive” encouragement of that belief. The authors’ exhortations to self-esteem are thus quixotically premised on a shattering of their readers’ prior sense of identity and trust. And the recommended path to healing is strewn with tragic confrontations and with the civil or criminal prosecution of heartbroken relatives.

Despite Bass and Davis’s protestation to the contrary, very little “moving on” is to be found in their Survivor narratives. As they admit, “Some women…go through an emergency stage that lasts several years…. [T]hey still feel suicidal, self-destructive, or obsessed with abuse much of the time.” The authors can’t comprehend that this suffering is typically brought on by their own suggestions and by those of the reckless therapists whom they have urged, in their words, to “believe the unbelievable” about their patients’ histories.

Bass and Davis now insist on the “compassionate” character of their book. Among accused parents, however, The Courage to Heal is known with good reason as The Courage to Hate. “First they steal everything else from you,” it says, “and then they want forgiveness too? Let them get their own…. It is insulting to suggest to any survivor that she should forgive the person who abused her.” Instead, the authors prescribe a cultivation of rage:

A little like priming the pump, you can do things that will get your anger started. Then, once you get the hang of it, it’ll begin to flow on its own…. You may dream of murder or castration. It can be pleasurable to fantasize such scenes in vivid detail. Wanting revenge is a natural impulse, a sane response. Let yourself imagine it to your heart’s content…. Suing your abuser and turning him in to the authorities are just two of the avenues open…. Another woman, abused by her grandfather, went to his deathbed and, in front of all the other relatives, angrily confronted him right there in the hospital.

Bass and Davis’s compassion, it seems, extends only to the women whom they have helped to wall off from the solicitude of their grieving families.

The authors dispute my account of the “knowledge base” underpinning The Courage to Heal, but they misrepresent both my argument and the known sources of their movement. In the early 1980s, both Bass and Judith Herman, who says that her intellectual home for the past two decades has been the Women’s Mental Health Collective in Somerville, Massachusetts, belonged to an informal Boston-area network of militant feminists who were gathering (always recalled) molestation stories from workshops, patient surveys, and support groups. By the mid-1980s, influenced in part by such writers as Alice Miller, Diana Russell, and Jeffrey Masson, those theorists of trauma were adding repression and dissociation into the mix, with the result that virtually any unhappy woman, with a little effort and assistance, could now lay claim to full membership in the corps of Survivors.

In her recent book Trauma and Recovery, Herman notes the contribution of social pressure in the eliciting of previously unconscious material:

As each group member reconstructs her own narrative, the details of her story almost inevitably evoke new recollections in each of the listeners. In the incest survivor groups, virtually every member who has defined a goal of recovering memories has been able to do so. Women who feel stymied by amnesia are encouraged to tell as much of their story as they do remember. Invariably the group offers a fresh emotional perspective that provides a bridge to new memories.*

One might say that the recovered memory movement was born when Herman, along with Bass and other anti-patriarchal activists, failed to greet such “new memories” with appropriate skepticism.

Bass and Davis’s third edition (1994) does show a dawning awareness that some of the accused and reviled may be innocent after all. Meanwhile, however, the authors display an ominous new interest in supposed women perpetrators and boy victims. As their gender bias thus becomes less prominent, the net of their inquisition continues to widen. And their fallacious diagnostic reasoning—epitomized in one quoted Survivor’s rhetorical question, “Why would I be feeling all this anxiety if something didn’t happen?”—remains as virulent as ever.

The authors of The Courage to Heal profess themselves indifferent to the threat of damage suits. I will take their word for it. Along with the False Memory Syndrome Foundation, I disapprove of prosecuting writers for the content of their ideas; the only proper response to Bass and Davis is to show how they have deceived themselves and others. No one, however, should underestimate the reverberating havoc they have unleashed upon vulnerable women and their families.

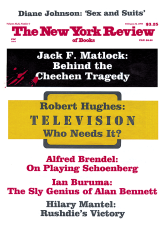

This Issue

February 16, 1995

-

*

Judith Lewis Herman, Trauma and Recovery (Basic Books, 1992), p. 224. For further insight into the movement’s origins, see chapter 3 of Mark Pendergrast’s Victims of Memory: Incest Accusations and Shattered Lives (Upper Access, 1995).

↩