1.

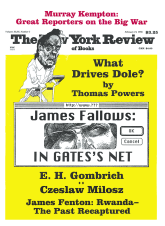

The most effective aspect of Bill Gates’s new book is its cover. A wonderful photograph, taken by Annie Leibovitz, shows a friendly-looking and casually dressed Gates standing on an isolated highway somewhere in the West. With his crew-neck sweater and penny loafers, with his warm expression and relaxed pose, Gates looks like the brainy young nephew in whom a family reposes its future hopes. Behind him, toward a horizon of pastel blues and pinks, the highway stretches straight, promising much. The image recalls other American fantasies of the next frontier and the open road. The message is, of course, that the competent, unthreatening Gates will guide us toward the information frontier.

The book itself is a less artful attempt to convey the same message. Within the computer industry there has been some puzzlement about why Gates would want to write a book at all. The advance paid for The Road Ahead is reported to have been $2.5 million, but Gates is the rare author of a best-seller who could have made more money by sticking to his day job. Depending on the valuation of Microsoft stock, Gates’s fortune is said to be worth at least $10 billion, and perhaps significantly more. Gates is dividing his royalties with two co-writers, and has announced that he will give his share of the money to charity. (The collaborators are Nathan Myhrvold, a highly respected computer scientist at Microsoft, of which Gates is chairman, and Peter Rinearson, a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist and software developer. For the record, Rinearson and I were friends and colleagues when we both were based in Japan.)

It seems unlikely that Gates’s primary motive in writing the book was to reveal the major insights he had developed in two decades of astonishing business success or to disclose his canniest ideas about future technologies and markets. (Gates, who turned forty last fall, was nineteen when he founded Microsoft with his partner Paul Allen in 1975.) The book seems meant mainly as a primer for people just beginning to be interested in the computer industry. Yet even on those limited terms it is puzzling, for the electronic landscape that Gates wants to describe has changed dramatically since the time he decided to write the book.

The Road Ahead was published just before Christmas 1995, but it had originally been scheduled to appear one year earlier. Gates observes sardonically in his foreword that writing a book turned out to be slower and more complicated than he had envisioned. “I innocently imagined writing a chapter would be the equivalent of writing a speech,” he says; but while he could crank speeches out easily at the office, “to complete the book I had to take time off and isolate myself in my summer cabin with my PC.”

In retrospect Gates may actually be grateful that writing the book proved to be so slow. The computer industry changed so much in 1995 that if The Road Ahead had appeared on schedule, late in 1994, its “vision” of the future might already seem seriously out of date, much like that of a book about Europe written just before the collapse of the Berlin Wall.

Through 1993 and 1994, computer industry analysts were deeply interested in the likely convergence of the video-game, computer, and cable-TV industries. Video-game machines, from companies like Nintendo, Sega, Atari, and 3DO, are present in far more households in America than are personal computers. Although Bill Gates’s Microsoft has become the best-known corporate name of the computer era, the Nintendo Corporation, of Japan, was in the early 1990s earning annual profits comparable to Microsoft’s by selling arcade-style games like Donkey Kong and the machines to play them on.1 Video-game machines are cheaper than personal computers and much faster at certain specialized functions, especially producing rapidly changing graphic displays.

Therefore, people who had a “vision” about the future of computing two or three years ago often speculated that the “set-top box”—essentially a combination of a video-game machine and a cable-TV controller, which sits on top of a household TV—might challenge or even displace the personal computer as the high-volume product of the electronic age. According to this view, the information that people wanted would come to their homes along existing cable-TV lines, which can carry vastly more data than ordinary phone lines can. People would sit in front of their TVs and choose various information offerings, much as they now channel-surf. An improved version of the remote controls for today’s TVs, equipped with a keypad, would allow people to send commands to the set-top box, providing a limited degree of “interactivity.”

Very few people put much emphasis on this possibility any more. During the last year the technical and financial excitement of computing has all concerned “the Net” and “the Web.” “The Net” is, of course, the shorthand term for the Internet, which was originally a scheme sponsored by the Defense Department to link its labs with American universities in an ingenious and robust way. Instead of connecting computers in a hierarchical, trunk-and-branch fashion, comparable to a city’s electric or water-supply network, the Internet ties computers together in an entirely decentralized system, analogous to a grid of streets crisscrossing a city. As a message leaves a computer in, say, Boston, bound for another one in Seattle, it is broken into a series of small “packets” of several characters apiece. Each packet is sent along the route of interconnected computers that is, at the instant of its dispatch, less crowded than any other path. At the receiving end, the packets, which may have come by completely different paths, are reassembled into a complete message.

Advertisement

During the cold war the great advantage of this approach was that it made the Internet virtually indestructible, even by an atomic blast. An electric network can be knocked out if you destroy its central station, but in principle the Internet could simply send messages on new paths if some of its nodes were destroyed. The same design concept now makes the Internet surprisingly “scalable”—able to absorb dramatically increasing traffic without becoming frozen by its version of gridlock. Still, the last year’s increase in traffic has been so tremendous that using the Internet now requires great patience. After learning the commands and protocols necessary to make connection with the Internet, after determining which Internet sites they might want to visit, and after typing in the proper site addresses, which are known as “URLs” (“uniform resource locators”) and which usually begin with the obscure code “http://www.,” most users still have to twiddle their thumbs and stare at the computer screen as they wait for data and images to rumble across the overburdened phone lines.

“The Web” is shorthand for the World Wide Web, a system allowing users to move from one Internet site to another and to inspect the information that is available there without remembering complicated commands and protocols. The Macintosh computer, applying concepts developed by Xerox, greatly simplified computing a decade ago by substituting a little picture of a disk-drive or a printer for the more complex commands that were necessary to work those devices. The sudden popularity of the Web has had a similar streamlining effect. While using a Web “browser,” a software program such as Netscape or Mosaic, you can inspect the information available at different sites—for instance, the full text of all pending legislation at the Library of Congress’s Web site, called Thomas, or a catalog of paintings held by the Louvre. To get an idea of where, among the world’s Web sites, which are increasing by many thousands per week, the information you want might be, you rely on specialized search programs like Yahoo and Webcrawler, which attempt to keep a current master list of Web sites.

When a person or a company sets up a “home page,” or Web site, it uses the Web’s “HTML,” or Hyper-Text Mark-up Language, to link information together in ways that might be interesting to the user. The Atlantic Monthly’s Web site, for instance, posts articles from its current issue—but includes links to related reference material. If you read an article about abortion, one link would take you to the original text of the Roe v. Wade decision, which is, for computer use, physically stored on a law school computer at Case Western Reserve, and another might take you to magazine articles on the subject from the 1920s. The concept of such “hypertext” links is not revolutionary—the physicist Vannevar Bush described it in his article “As We May Think” fifty years ago—but they have caught on in practice only in the last two years.

At the moment, many people and companies experiment with the Web more because it’s a novelty than for immediate practical benefit. The different ways of finding the information you may need remain limited. Web-based shopping experiments have generally proven disastrous, since people find it easier and more satisfying to call a 1-800 number if they don’t want to go to the store. The whole system can seem a nightmarish extension of cable TV: five million channels, but not much one wants to see. In interviews Bill Gates has scoffed at some of the current euphoria surrounding the Internet. An idea that would sound stupid on its own, he says, suddenly becomes attractive if the words “for the Internet” are tacked on. In his book he envisions a broader, all-embracing data network that will use wireless communications to transmit information to devices much smaller and more portable than even the most miniature of today’s portable computers. Which aspects of the Web will eventually prove most useful, popular, and profitable will not be clear for years. Nonetheless it already seems evident that the last year’s developments in networked computing will have a significant effect on the way we use computers in the future.

Advertisement

This brings us back to the “vision” of Bill Gates’s new book. When Gates signed the contract to write The Road Ahead two years ago, very few people foresaw how radically the Internet would be changing the computer business by 1995. Those prescient few probably did not include Gates; through 1994 and 1995, as talk about the Net became more and more dominant in the industry, Microsoft was slower than Sun, Netscape, and arguably even stodgy IBM in shifting its emphasis to Internet products. (Through the fall of last year, IBM’s chairman, Louis V. Gerstner, was giving speeches that increasingly stressed IBM’s commitment to a nework-related approach. Gates gave a similar news conference in December.) Therefore, whatever Gates may have had in mind in 1993 as a vision for computing has probably been under reconsideration as well.

Still, Gates’s account of the different phases of his career during the last twenty years gives his book some coherence. During the first half-dozen years of Microsoft’s existence, in the mid- and late 1970s, personal computers (then called “microcomputers”) were a hobbyist’s oddity. Through the next dozen years, from the introduction of the IBM Personal Computer in 1981 and Apple’s Macintosh in 1984 to around the beginning of the Clinton administration in 1993, personal computers began to be like cars. They were simultaneously a mass commodity; a source of shared lore and experience; an opportunity for tinkering and status competition primarily among men; a means of speeding up the operations of countless other industrial processes, from the lay-out of magazine pages to the handling of bank transactions; and a major industry in their own right. The stadium where the San Francisco Giants and 49ers play, née Candlestick Park, was recently renamed 3Com Park, after a company that supplies components for computer networks. Traditionalists complained about the shameless commercialization of sports. But that trend has been underway for decades. The real significance of the change was to show that computer companies were joining the makers of beer, cigarettes, soft drinks, and automobiles in wanting name-brand recognition with the mass public.

Unlike cars in recent decades, computers have been a symbol of America’s technical dynamism compared to the rest of the world’s. At the beginning of this mass-commodity stage, Bill Gates’s name was hardly ever in the paper and Microsoft was just another struggling firm with forty employees. By the end, to many Americans Bill Gates was as identified with the computer era as Henry Ford was with the automobile age and Thomas Edison with electric light.

As with other products that profoundly changed daily life—the automobile, TV—the computer has assumed so powerful a position that it is provoking second thoughts. Gates must have sensed that the next round of public questions about computers would not be, “How do they work?” or “How big is yours?” but “Are they good for society?” or, “In what ways might they be bad?”

Within the computer industry Gates has already experienced a wave of second-guessing. Since the early 1980s, as many people (led by Gates) have made fortunes, especially in software, those who follow the computer industry and are interested in new computer developments—“the computer culture”—have been torn between adulation of the new, rich, young entrepreneurs and resentment of them when they seem too rich, or too powerful. IBM was hated when it muscled its way into the fledgling personal computer industry in 1981. With its quasi-monopoly power it seemed destined to crush all competitors.

For years Bill Gates enjoyed a dragon-slayer’s image in the industry, because of the universal perception that at age twenty-five he had talked mighty IBM into the most disastrous contract in its corporate history. This was the deal by which IBM agreed to by from tiny Microsoft the operating system for its new personal computer, the software that was to become the world’s standard. Speculation has gone on for years about exactly why IBM made this fateful decision, which gave Microsoft its crucial break and was a significant factor in IBM’s difficulties throughout the 1980s.

The most convincing explanation, presented in the authoritative biography of Gates by Stephen Manes and Paul Andrews, is that the inventive, anti-bureaucratic team within IBM that was developing the original PC wanted to get the machine on the market as quickly as possible. It seemed faster and easier to buy an operating system from an outside vendor than to rely on the competent but slow IBM establishment to produce it. Fifteen years later, Gates and Microsoft still enjoy some of its fresh-faced youthful-upstart image in the national press. But within the computer culture, Microsoft has become IBM: its concentration of power is feared by all its competitors.2 The Road Ahead can, I think, best be seen as a preemptive effort to explain that Gates himself, the company he has built, and the industry he symbolizes are all benign forces to be trusted and believed in.

2.

Gates’s presentation of himself in the book is consistent with the blandness of his formal speeches and most of the interviews he has given over the years. But it is also puzzling. Even the competitors who most fear and resent Microsoft’s dominance of the industry seem genuinely in awe of what Gates has done. They admire him not for the boy-inventor qualities usually stressed in TV or magazine profiles but for the relentlessness with which he has exploited his advantages, seen where potential profits might lie, and kept his company toughly competitive when it could have become lax. What impresses many people about Microsoft is less that it has produced three billionaires—Gates, the company’s co-founder, Paul Allen, and Gates’s longtime associate and second-in-command, Steve Ballmer—than that it has produced many hundreds of millionaires. These people are, of course, rich because of the value of Microsoft stock: so great has been the financial market’s opinion of Microsoft that the company’s stock market valuation has in the last year been roughly equal to IBM’s, even though IBM’s annual revenues have been about twelve times larger. (More than $60 billion for IBM, versus about $5 billion for Microsoft.)

Some Microsoft employees have viewed working for the company as an ordeal to be withstood until “vesting day,” the moment their stock options become valuable, and not a day longer. The plot of Douglas Coupland’s novel Microserfs, which depicted the lives of Microsoft programmers, involved the company-wide obsession with Microsoft current stock price and the countdown to one fortunate character’s “vesting day,” after which she planned to quit.3 Such a concentration of tension and greed could easily destroy a company, but Coupland’s book and most other accounts of Microsoft emphasize how skillfully Gates has been able to keep smart people trying their best to please him. One of the most illuminating of these accounts, I Sing the Body Electronic by Fred Moody, describes the torments that a team of young Microsoft programmers went through as they tried to get a product for children, called Explorapedia, ready in time for the announced sales deadline. They stayed up all night, they pushed themselves to the limit, they fought and cried—and still they slightly missed the deadline. After telling their story Fred Moody concludes:

Looking back at Explorapedia and its creation, I can see now that Gates and his managers had cunningly set goals and standards that would prove impossible to meet. By arbitrarily shortening [the schedule for one component], they guaranteed that the eventual success of its team would be seen by team members as a failure. It was exactly what Gates had done to them on Encarta [a predecessor encyclopedia]: while giving his employees the means to win, he also ensured that they would interpret their victory as defeat. There would be no laurels for them to rest upon; instead, they would dive immediately into their next project hoping to redeem themselves.

An informative if somewhat plodding business-school analysis of the company’s growth, Microsoft Secrets, by Michael Cusumano and Richard Selby, similarly contends that Gates has been brilliant in finding the economic and psychological methods that would best motivate fifteen thousand potentially fractious employees. The “Meeting with Bill” has become a legendary part of Gates’s management strategy. Before Microsoft decides to develop an important new program or release it to the market, the program’s developers undergo a kind of oral examination conducted by Gates. Again and again, the authors tell us, he immediately detects the weak or ill-thought-through aspect of the plan and then ridicules those responsible for the error. In many organizations this could lead to overcautious, embittered employees. At Microsoft it seems to encourage them to look extra-hard for weaknesses themselves. Smart people of the sort hired at Microsoft have no trouble coming up with ideas. Gates has instilled the belief that the only truly great ideas are the ones that sell. “This guy is awesomely bright,” one Microsoft manager told Cusumano and Selby. “But he’s unique in a sense that he’s the only really bright person I’ve ever met who was 100 percent bottom-line oriented—how do you make a buck?” The authors say that Gates’s instincts make him a gifted leader and “the most underrated manager in American industry today.”

In his business life the author of The Road Ahead is an interesting and complex figure, as driven and as capable of driving others as Lyndon Johnson was in politics. The memoirs of some members of his White House staff describe Johnson as stormy, wily, and manipulative, yet in his formal speeches he struck an unconvincingly prim, states-manlike pose. Gates has done something similar. The intense, intuitive man who ridicules sloppy thinking is missing from the book, replaced by someone determined to sound respectable in front of the grown-ups. He is trying to sound like the man on the jacket, rather than the man dominating the Meetings with Bill.

The most interesting comments in Gates’s book are in a chapter called “Race for the Gold,” in which he sizes up the prospects for making money on the Internet, and also in the passages displaying the unself-conscious fascination with gadgets that characterizes Gates’s vision of the ideal future. The clearest example of the latter occurs in his description of his dream house in Seattle, which has been under construction for the last three years at an estimated cost of some $30 million. People who come to visit the house will get personalized badges or pins at the door, coded with a list of all their tastes and access rights—how warm they like a room to be, into which rooms they may and may not go. The following account is not intended to describe how Gates plans to drive his guests crazy but to express his brave new ideas of hospitality.

If you regularly ask for light to be unusually bright or dim, the house will assume that is how you want it most of the time. In fact, the house will remember everything it learns about your preferences. If in the past you’ve asked to see paintings by Henri Matisse or photographs by Chris Johns of National Geographic, you may find other works of theirs displayed on the walls of rooms you enter. If you listened to Mozart horn concertos the last time you visited, you might find them on again when you return…. We’ll also be able to “tell” the house what a guest likes. Paul Allen is a Jimi Hendrix fan and a head-banging guitar lick will greet him whenever he visits.

Gates’s version of his company’s history sounds more respectable but less interesting than the unvarnished truth would have been. He alludes only in passing to the factor that, according to both friendly and hostile observers of Microsoft, was indispensable to the company’s success—his determination to control the standards for computer programming.

Most Americans are familiar with the war over standards in the VCR business a decade ago. Sony devised a “Beta” format for its VCRs. By some technical measures this was superior to the VHS format promoted by Matsushita. The Matsushita format had an early edge in the market because its cassettes could record longer programs—and once it had a small edge, it soon had a huge edge. Customers wanted to buy the machine that would play the widest variety of movies, and movie companies wanted to produce cassettes that would play in the greatest number of machines. Ultimately the Beta machines all but disappeared.

Long before the VCR story played out, Gates applied a similar logic to the emerging personal computer business. In the early 1980s there were at least half a dozen “operating systems” for personal computers, plus a variety of disk formats for storing information. (The difference among formats is roughly comparable to the difference among 33, 45, and 78 rpm records—when there were records.) Gates knew that one of these systems would become standard, and he was determined that it be his. The history of the software industry is largely the story of how Gates achieved that goal. In The Road Ahead he passes off this accomplishment as a fortunate combination of “great software” and hardwork. Other accounts have emphasized the importance of Microsoft’s aggressive pricing strategies (including one discontinued last year, as part of a consent decree with the Justice Department), its courting of the computer industry trade press, and other tactics that finally drove competing standards from the field.

While it skimps on explaining how Microsoft got control of the industry’s standards, The Road Ahead does a remarkably good job of explaining the fundamentals of the computer revolution to people who remain hazy about what has really happened. For example, the concept of “binary notation”—that any number can be expressed as a combination of 0s and 1s—is the foundation of everything that computers do. The concept is now taught to third-graders across the country but remains off-putting to many adults; this book contains as lucid a description of binary notation and its consequences as I have ever seen.

Also with great clarity Gates explains the implications of “Moore’s Law,” which has had about as big an impact on the computer era as Boyle’s Law had on the age of steam engines. Moore’s Law, actually a rule of thumb, was propounded three decades ago by Gordon Moore, a founder of the dominant semiconductor company Intel. Moore estimated that the computing power available for a given price would double at a regular interval, which now seems to be about eighteen months. The compounding effect of Moore’s law means that the ordinary $2500 personal computer of today can process information 250 times faster than a comparably priced machine at the time the Macintosh was introduced. People who use computers don’t appreciate how fast the machinery itself has become, since much of the increase in speed has been sopped up by the demands of ever more complex software. But computing power is now so cheap that it is invisibly built into devices all around us, Gates says. The inescapable voice-mail systems of the 1990s are run by computer chips that would have cost thousands of dollars apiece a dozen years ago. A dozen years from now, computers should be 250 times as powerful, or one-250th as expensive, as they are today. American life has already been changed by computers, but what has happened in the last fifteen years is, Gates says, barely an introduction to what the era of practically free computing power will mean.

3.

What will it mean? The Road Ahead provides answers of two sorts. It has a detailed discussion of the appliances and tools we might be able to buy a decade from now, and a cursory consideration of whether we will like everything the tools bring in their wake.

The one device that symbolizes all the others is the “wallet PC,” a miniature computer that will cover your information and communication needs. The wallet PC will let you send and receive messages, like one of today’s pagers, and view them on its tiny screen. You will be able to play games on it. You can get tips on where the nearest gas station, restaurant, or automatic cash machine may be. You may not even care about the cash machine, since the wallet computer will carry virtual electronic cash that you can use for any purpose that cash is used for today. Gates says: “At a meeting you might take notes, check your appointments, browse information if you’re bored, or choose among thousands of easy-to-call-up photos of your kids.”

Like some of Gates’s other predictions, this one combines small extensions of existing functions with unlikely technological leaps. Many people already send electronic mail or check stock quotes by means of portable computers and wireless modems. But how about jotting notes on a little pad the size of a postcard, and then having the computer convert handwritten scrawls into usable data? Programs capable of reliably converting many different styles of handwriting into a standard, readable text, like programs that can translate German into English or programs that can recognize spoken commands from a wide variety of speakers, are often said to be five or ten years away from perfection—and will probably stay that way for decades.

The real significance of the wallet PC, however, is its “connectedness.” Gates emphasizes that with cheap computing and greatly expanded communications networks, you will be in touch with all the details of your life wherever you are. You can easily contact your family or associates. You can instantly call up any business, personal, or financial data you want. And since all the institutions that you deal with will be connected as well, the frustrations that are now summed up by the phrase “couldn’t get through” will fade from your life. When you decide what type of food you’d like to eat, your wallet PC will check the restaurant listings, even in a strange town, and tell you the least crowded place to go and the safest way to get there. It will deal with airline computers to find the fastest, cheapest way to reach your destination. It will schedule your meetings. Should you be hit by a bus, it can call up your lifetime medical records. Perhaps most important to Gates, it will provide a nearly perfect tool for matching buyers and sellers around the world.

You are in Oregon and want to buy a 1964 Mustang. I am in Florida and have a 1964 Mustang for sale. Under today’s circumstances each of us might be restricted to the buyers and sellers we could find locally. You might have to pay more for your car, and I might have to settle for less, than if we could search for the ideal customer no matter where he might be. According to Gates, the wallet PC and the communications structure for which it stands will let us do just that. As malls and national chain stores have displaced Mom-and-Pop stores, as catalog-sales companies with 1-800 numbers have created a national market in which customers can shop for the best price, what economists think of as the “imperfections” and inefficiencies of the market have been reduced. They will virtually disappear, Bill Gates says, when we all are wired. Total communications will give us what he calls “friction-free capitalism,” in which nothing will stand between willing buyers and sellers making the best possible deal.

This concept may, in unintended fashion, represent the greatest value of Gates’s book, because it foreshadows the most important arguments we will soon be having about computers. The most-noticed criticisms of the computer age that have appeared in the last two years have concerned its cultural effects. Sven Birkerts, in The Gutenberg Elegies (Faber and Faber, 1994), warned that writing, reading, and nervously “interacting” on a computer destroy the qualities of mind developed by writing on paper and reading books. Vartan Gregorian, the president of Brown, made a similar case in the Bulletin of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. “The popular prediction that electronic communication would create a global village has been shown to be wrong,” he said. “What is being created is less like a village than an entity that reproduces the worst aspects of urban life: the ability to retreat into small communities of the like-minded, where we are safe not only from unnecessary interactions with those whose ideas and attitudes are not like our own, but also from having to relate our interests and results to other communities.”4

Politicians warn that the Internet will expose children to pornography, and indeed there is porn available in amazing varieties. In January the Arts and Entertainment Network ran a documentary illustrating just how rapidly and creatively Internet entrepreneurs are working to satisfy sexual fantasies of every sort. The main consolation to parents worried that their children may stumble across pornography is that not much of the material is available for free. Like 1-900 sex-chat lines, the Internet porn sites usually charge steep fees and require the user to give a credit-card number. Clifford Stoll, a longtime computer expert, complains in Silicon Snake Oil that while computers seem to provide variety and choice, in fact they are robbing life of its savor. “Real mail has pretty stamps and post-marks,” Stoll said. “Here’s a pressed flower from some faraway summer. These letters bring back promises, memories, and smiles.” E-mail, by contrast, is machine-like and dead. Numerous writers have worried about the tendency of electronic exchanges to fly off into vituperation, or to be dominated by political extremists, most of them (as it happens) from the right wing.

Clearly computers will have large cultural effects, as will any shift in technology. Yet having myself worked with and written about computers for nearly twenty years, I can’t believe that their most important or their worst effects will be on contemporary culture. Most of what computers make possible is an extension of previous habits and functions. People once wrote letters; now they send e-mail. It is different, but it’s also the same. I would be surprised if computers change the tone of life more radically than the telephone did. Their cultural impact probably won’t be as great, and cannot be as bad, as that of TV.

The most worrisome cultural implication of the new developments may be the one least discussed in print so far: the sudden concentration of the number of “content providers,” as NBC allies itself with Microsoft, CNN is absorbed by Time, Disney buys ABC, and the once-diverse universe of broadcasters, publishers, software companies, and entertainment studios reduces itself to a handful of giant combines. But this trend toward concentration is not mainly caused by computers—which are, indeed, often described as the main instrument for a decentralized, nonhierarchical communication system.

The real problem is economic. In a convincingly detailed and technical book called The Trouble with Computers, Thomas Landauer, the former director of Cognitive Science Research at Bellcore (the successor to Bell Labs), observed that through the 1980s, American industries invested billions of dollars in information technology with little visible payoff. Explanations for this “productivity paradox” varied. Perhaps, as Landauer argued, the equipment and programs were poorly designed. Perhaps the measures of productivity were imprecise.

Whatever the origin of that problem, it now appears to be ending. The evidence is precisely the wave of “downsizing” and apparently permanent job loss that has affected whitecollar America. The technical definition of rising productivity, of course, is more output with fewer workers. With the help of computer technology, US corporations have begun winning the productivity battle. The success is reflected in rising profits, in stock prices that soared in 1995—and, just as clearly, in layoffs. A dozen years ago, when steel and auto makers were announcing layoffs, Americans could explain away the loss of jobs as the death throes of badly managed, out-of-date industries. Now the most modern industries are the ones losing workers fastest. “The very companies most closely associated with building the Info Highway have been among those shedding jobs in the biggest numbers,” Daniel Burstein and David Kline write in Road Warriors:

IBM announced 85,000 job cuts between 1991 and 1995; AT&T, 83,000; NYNEX, 22,000; Hughes, 21,000; GTE, 17,000; Eastman Kodak, 14,000; BellSouth, 20,000; Xerox, 10,000; Pacific Telesis, 10,000; US West, 9,000. … It would appear that there is a new kind of macroeconomic Moore’s Law showing up: As the rate of new wealth creation fueled by digital technology rises, the number of people required to produce it is decreasing.

The most important fact about these layoffs is that they result not from corporate failures but from what is defined as success—progress toward a “friction-free” world of the most efficient production and distribution. But they create a society of winners and losers that is unpleasant even for the winners to live in.

Gates barely acknowledges the challenge of dealing with deep economic dislocations. “I’ve thought about the difficulties and find that, on balance, I’m confident and optimistic,” the richest man in America declares. In a chapter called “Critical Issues,” he emphasizes that the country needs to educate more of its people better. He is unable to move past that familiar and abstract prescription—but, in fairness, few other people have come up with specific plans to deal with the “downsizing” and “reengineering” that are made possible by computerization. In Road Warriors, Burstein and Kline conclude that continued improvements in technology will make continued loss of jobs inevitable—“unless, as a matter of social policy, we choose to steer the U.S. economy in a different direction” (their italics). They mean it as an exhortation; at the moment it seems instead a gloomy and so far unrefuted diagnosis.

This Issue

February 15, 1996

-

1

See my article on Game Over, David Sheff’s book about Nintendo, The New York Review, March 24, 1994.

↩ -

2

The best job yet of explaining the grounds for the fear was James Gleick’s article “Making Microsoft Safe for Capitalism,” in the New York Times Magazine, November 5, 1995. He explained that the dominance of Microsoft’s DOS and Windows operating systems gave the company de facto control of a worldwide industrial standard. Any company hoping to market a word-processing program or a spread-sheet must first be sure that it is compatible with Microsoft’s operating systems. The situation is very much as if one company had the right to determine the voltage that would be used in the nation’s electric power system, including the right to change the voltage when it chose—and yet was competing against other companies to sell electric appliances. Nonetheless, Gleick said, Microsoft staunchly maintained that its operating systems were its own proprietary assets, to use or change as it saw fit. Gates does not comment on this issue in his book; indeed, he says nothing whatever about competitors’ complaints against Microsoft, or about the federal antitrust actions against Microsoft during the last five years.

↩ -

3

“Most staffers peek at WinQuote [which shows the Microsoft price] a few times a day. I mean, if you have 10,000 shares (and tons of staff members have way more) and the stock goes up a buck, you’ve just made ten grand! But then, if it goes down two dollars, you’ve just lost twenty grand. It’s a real psychic yo-yo. Last April Fool’s Day, someone fluctuated the price up and down by fifty dollars and half the staff had coronaries” (p. 6).

↩ -

4

Vartan Gregorian, “A place Elsewhere: Reading in the Age of the Computer,” Bulletin of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, January 1996,p.56

↩