In 1982, when Blake Morrison and Andrew Motion published their Penguin Book of Contemporary British Poetry, Seamus Heaney exploded. He had had enough. He was not British, and he was fed up with being called British, or anything other than Irish. But since his work had first appeared with Faber in 1966, it had regularly been called British, and it had appeared in such anthologies as Edward Lucie-Smith’s British Poetry Since 1945 (1970), Jeremy Robson’s The Young British Poets (1971), Michael Schmidt’s Eleven British Poets (1980), and even, in 1968, Karl Miller’s Writing in England Today: The Last Fifteen Years. It was time to set the record straight.

Heaney’s riposte to Morrison/Motion took the form of a 198-line poem, “An Open Letter,” headed by a quotation from Gaston Bachelard: “What is the source of our first suffering? It lies in the fact that we hesitated to speak…. It was born in the moment when we accumulated silent things within us.” And the poem itself tells us that Heaney had thought about this matter for weeks, months, that he was embarrassed to bring the whole thing up because Morrison had been his “good advocate” in writing a book on him, that he was disappointed particularly because he had understood that the anthology was going to be called Opened Ground, a phrase from one of his poems. He had wondered whether to let the matter drop:

Anything for the quiet life.

Play possum and pretend you’re deaf.

When awkward facts nag like the wife

Look blank, go dumb.

To greet the smiler with the knife

Smile back at him.1

But Heaney felt that if he dithered, Hamlet-like, he would pay for it in Act Five, that silence was an abdication, that he had to refuse the adjective “British.” And so he administered a “simple lesson”:

Caesar’s Britain, its partes tres,

United England, Scotland, Wales,

Britannia in the old tales,

Is common ground.

Hibernia is where the Gaels

Made a last standAnd long ago were stood upon—

End of simple history lesson.

As empire rings its curtain down

This “British” word

Sticks deep in native and colon

Like Arthur’s sword.

Heaney was unhappy with the Burns stanza he had chosen, which leads him into many awkwardnesses, as here where he seems to overlook the fact that there were also Gaels who made their last stand in Scotland. And do we imagine that, writing in prose, he would have distinguished Catholic from Protestant by calling one lot native and the other colon? It seems unlikely.

There were twenty poets in Morrison/ Motion, six of whom came from Northern Ireland. Heaney specifically says that he is speaking only for himself, not on behalf of the whole group:

(I’ll stick to I. Forget the we.

As Livy said, pro se quisque.

And Horace was exemplary

At Philippi:

He threw away his shield to be

A naked I.)

This has more grandeur and passion than the context might seem to justify, but the decision to speak only on his own behalf was an important one for Heaney in another respect. For years he had been resisting the pressure to speak for the Republican movement. In his new collection, a poem called “The Flight Path” recalls meeting a Republican on a train in 1979 during the “dirty protest” at Long Kesh and being challenged with:

“When, for fuck’s sake, are you going to write

Something for us?” “If I do write something,

Whatever it is, I’ll be writing for myself.”

He will not, he is saying, put his poetry at the service of the cause. He will only speak as an individual. Nevertheless, in “An Open Letter,” he comes close to flag-waving when he says:

be advised

My passport’s green.

No glass of ours was ever raised

To toast

The Queen.

The vehemence of this refusal to be called British took many people by surprise and made Morrison/Motion look a little foolish. Heaney was the star show in their anthology, the one they deliberately placed first, the one they hailed as the most important new poet of the previous fifteen years. Nor was it the only time that Morrison had written of Heaney as being British. In his book, also published in 1982, he said that Heaney “grew up in the North of Ireland, which technically at least makes him British.” He calls his blend of sexual passion and domestic affection “unique in modern British poetry” and, writing about Field Work (1979), he says the sequence “marks Heaney’s return not just to the countryside but to the mainstream of English Poetry: having begun in imitation of Ted Hughes and then looked more to his own countrymen, he now takes his place in an English lyric tradition that includes Wyatt at one end and Wordsworth at the other.”2

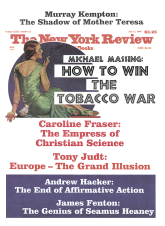

Advertisement

Morrison and Motion had naturally hoped that their anthology would be seen as a kind of landmark. They wanted it to be, for its time, what Al Alvarez’s The New Poetry had been in its day. “British poetry,” they said in their introduction, had taken “forms quite other than those promoted by Alvarez,” and a part of the reason for this was the “emergence and example of Seamus Heaney…. Heaney is someone Alvarez could not foresee at the time and someone he has attacked since.” And they contrasted the nakedness of the style of poetry Alvarez admired with the obliquity they detected in Heaney.

One turns to Alvarez’s review of Field Work,3 which was not only an attack on Heaney but also an attack on his English admirers in academe, people like Christopher Ricks and John Carey, who had recognized Heaney’s gifts from the beginning of his career (I think that what they were recognizing was a successor to Ted Hughes) and were now declaring that in Heaney “Britain has, at last, another major poet.” This seemed grossly disproportionate to Alvarez. Heaney’s current reputation amounted to

a double betrayal: it lumbers him with expectations which he may not fulfill and which might even sink him, if he were less resilient; at the same time, it reinforces the British audience in their comfortable prejudice that poetry, give or take a few quirks of style, has not changed essentially in the last hundred years.

And now comes the passage which, if he read it, would most have stuck in Heaney’s craw:

If Heaney really is the best we can do, then the whole troubled, exploratory thrust of modern poetry has been a diversion from the right true way. Eliot and his contemporaries, Lowell and his, Plath and hers had it all wrong: to try to make clearings of sense and discipline and style in the untamed, unfenced darkness was to mistake morbidity for inspiration. It was, in the end, mere melodrama, understandable perhaps in the Americans who lack a tradition in these matters, but inexcusable in the British.

In other words, Heaney’s “abrupt elevation into the pantheon of British poetry” was a symptom of what was wrong with British culture. Our critics were dedicated to “safety, sweetness and light.” They showed “a curiously depressing refusal of everything that is mysterious and shaking and renewing in poetry.” And they reminded Alvarez of Ophelia:

Thought and affliction, passion, hell itself,

She turns to favor and to prettiness.

There is an interesting example, in what Alvarez says, of the use of Eliot for purposes of cultural intimidation: if it is right to admire Heaney, then Eliot must have lived in vain, and not only Eliot but Lowell and Plath as well. This is the line. This is the tradition. This is the canon being wheeled into action. Astonishingly absent is any interest in the Irish dimension, except in this: Alvarez tells us that “since Congreve and Sterne there has always been at least one major Irish star on the British literary scene.” At the time he is writing, it should be Beckett, but Beckett is too radical and experimental. Heaney is “far less unsettling.”

The implication seems to be that that is therefore all Heaney is—an Irish entertainer on the British cultural scene, a symptom of what is wrong with British culture. It must have been exasperating to Heaney. If you look at what Alvarez had recommended, in the influential introduction to The New Poetry, as a “new seriousness”—defined as “the poet’s ability and willingness to face the full range of his experience with his full intelligence”—and you see how Alvarez preferred the example of Hughes to that of Larkin, you might well have expected him to recognize in Heaney the sort of poet he had had in mind, had campaigned for. One might have predicted that North at least would have appealed to him.

Most exasperating of all, though, would be to feel that these misapprehensions about your nationality were, in part, your fault. For it would never have been so easy for the British to take whatever they liked from Ireland and call it British if a protest had been lodged a little earlier. That was the significance of the quote from Bachelard. Heaney was in a weak position, and knew it, which is one reason why “An Open Letter” is not a good poem (the other being that its versification is atrocious).

“An Open Letter” was a poor poem but an important event. It made its point and its point was not forgotten. It made its point on behalf of one writer, but established that point on behalf of a whole group. One no longer assumes—this is the crucial difference between then and now—that the political geography of the United Kingdom is coterminous with the cultural geography.

Advertisement

In the last of his Oxford lectures, given in 1993, Heaney says

…I wrote that my passport was green, although nowadays it is a Euro-, but not an imperial, purple. I wrote about the colour of the passport, however, not in order to expunge the British connection in Britain’s Ireland but to maintain the right to diversity within the border, to be understood as having full freedom to the enjoyment of an Irish name and identity within that northern jurisdiction. Those who want to share that name and identity in Britain’s Ireland should not be penalized or resented or suspected of a sinister motive because they draw cultural and psychic sustenance from an elsewhere supplementary to the one across the water.

This represents a considerable rewriting of “An Open Letter.” The notion that there might be such an entity as Britain’s Ireland was specifically ruled out by the insistence that Britannia is Britannia and Hibernia is Hibernia and that’s that. The lines “No glass of ours was ever raised/To toast The Queen” have an aggressive Republican tone quite different from the statement: I draw cultural and psychic sustenance from an elsewhere supplementary to the one across the water, as if, for the Northern Ireland Catholic, his Irishness were a kind of wheat germ which he sprinkled every morning on his—what would it be? on his Britishness?

The embarrassment behind the rewrite, so many years later, of a poem which he published only in pamphlet form, is indicative perhaps of a lingering sense that, though he had no alternative but to make his stand, the stand itself was some kind of betrayal, or some kind of slap in the face of people to whom he was, in various ways, obliged. “Now they will say I bite the hand that fed me” is a Heaney line in a slightly different context—a bitter anticipation of reproach. But Heaney as a person and as a poet has a terrific sense of obligation and often expresses guilt that he might not have lived up to the clearly impossible standards he set for himself or that others have been happy to set for him.

The general praise that greeted his being awarded the Nobel Prize last year might tempt one to forget that this immensely popular poet has often had a bumpy ride, that he has not been short of critics, not least among his fellow poets. “Certainly,” says the Protestant Ulster poet James Simmons, “it began long ago. In those old gatherings under the auspices of Philip Hobsbaum in Belfast it was obvious that Seamus was being groomed for stardom.”4 I would put this differently—not that I was over at those old gatherings (in which Hobsbaum, the English poet, gave encouragement and criticism to a generation of young Ulster writers). The fact is that no poet gets “groomed for stardom.” What on earth would the process be? But that he was tipped for stardom, that he gave, somehow, warning of the talent to come—that I can believe.

And behind this tipping for stardom lurked the awesome thought: Who will inherit the mantle of Yeats? And it appeared that Yeats had only one mantle, and that it was not to be divided. Certainly in Heaney criticism there is a topos: Why does Heaney get all the attention, when poet X or Y is so much more this, so much more that? It seems Heaney was thought to have had a knack of soaking up all the available attention.

Here is Simmons again, in the same, avowedly Cassius-like essay:

I remember feeling curiously angry and betrayed when I first reviewed Wintering Out. I had thought of Seamus as an ally in the general struggle to liberalise and reform Ulster, but he seemed to be retreating into the tribe, excluding Protestants, fostering resentment, betraying the tougher Catholic spokesmen of previous generations such as O’Faolain, O’Connor and Kavanagh. So many of the resentments he presents as specifically Catholic and Ulster are applicable to the poor universally, and there is a positive left-wing movement in which the human race has been trying to pull itself up by its bootstraps for centuries. Heaney’s feelings seem to operate in isolation from this.

Two betrayals here—betrayal of the joint political effort to liberalize Ulster, and betrayal of the tougher old Catholic writers of yore. Nor are these going to be the last betrayals on the list.

It is astonishing how often in the poetry of this century this theme of betrayal crops up. Pound of course is the big one—lucky to get away with his life. Then Auden was bitterly accused of betrayal when he moved to America. And was not Eliot’s espousal of England as a cause seen as a kind of betrayal? Sassoon betrayed his class, or wanted to. Lowell did betray his class, and in stirring style, when he refused to serve in a war whose prosecution, he thought, constituted a betrayal of his country (because the original war aims had been perverted to encompass the total destruction of Germany and Japan). He had his ancestors on parade when he announced his betrayal to no less a person than the President of the United States.

Heaney, so far in this story, has betrayed nationalism as represented by the IRA, liberalism as represented by Simmons, the tougher Catholic writers of yore, modernism as represented by Eliot, Lowell, and Plath—an impressive list of stabbings in the back. And it doesn’t end there. His move South was a betrayal of the North. Working in the States was Yankification. Everything turns out to be a betraying of something.

But I suppose that one is not accused of betrayal unless one is recognized as a leader, and behind many of these attacks there is a recognition of a preeminence either presaged or already gained. The attacks were certainly not afraid to wound. Ciarán Carson, another Ulster poet, wrote that in North Heaney seemed “to have moved—unwillingly, perhaps—from being a writer with the gift of precision, to become the laureate of violence—a mythmaker, an anthropologist of ritual killing, an apologist for ‘the situation,’ in the last resort, a mystifier.”5 One is curious, coming across such a passage, to look up where it came from. “Laureate of violence” is a killing phrase, and one expects a sustained argument to support it. But the review turns out to be as much an attack on the Faber publicity machine as on Heaney: it is the usual fraternal animus against an excessively hyped book.

The other often-quoted passage from Carson’s review discusses the poem “Punishment” and the lines:

I who have stood dumb

when your betraying sisters,

cauled in tar,

wept by the railings,who would connive

in civilized outrage

yet understand the exact

and tribal, intimate revenge.

This comes at the end of one of the “bog poems” which form the first section of North in a description of a presumed adulteress drowned in the bog at some time in prehistory. Carson says that Heaney seems to be offering his “understanding” of the situation almost as a consolation. He goes on:

It is as if he is saying, suffering like this is natural; these things have always happened; they happened then, they happen now, and that is sufficient ground for understanding and absolution. It is as if there never were and never will be any political consequences of such acts; they have been removed to the realm of sex, death, and inevitability.

That might be fair criticism—of a passage which caused consternation among numerous critics, among them Blake Morrison and Edna Longley—but it does not make the case that he was a “laureate of violence.” Simmons goes much further:

The poet’s tenderness is troubled by the thought that he would have done nothing to save her had he been there: as he has not saved the local Catholic girls tarred and feathered for going out with soldiers; but suddenly we find he is on the side of the torturers. The “little adulteress” whose “tar-black face was beautiful” has “betraying sisters,” and the poet writes of his own public words condemning the torturers as “conniving.” He leaves us with the statement that he understands “the exact/and tribal, intimate revenge.” He does not seem to be confessing or apologizing. That’s where it stands. This is very exciting and interesting. You wish he would say more.

Note, with this piece of malicious provocation, how astonishingly far we have come from the Heaney depicted by Alvarez, the safe Irish entertainer playing to an essentially timid British audience. Here we have a laureate of violence who is on the side of the torturers. And Simmons’s malice is revealed by his affecting to welcome this revelation of the real, hitherto unsuspected Heaney—as if it would simply be healthier to thrash all this out in public. This is one of those “open minds as open as a trap” at work. Simmons knows perfectly well that Heaney is not on the side of the torturers. If the poems in the first part of North were worrying to his genuine (as opposed to ironical) admirers, it must be because they sometimes failed to reassure the reader about the difference between understanding the processes at work (understanding them, with a full sense of the terror involved) and understanding-as-forgiving or even as conniving.

Nothing would have been easier for Heaney, had he bought the Provisional IRA line, than to put his Muse at the service of the cause. As a young man, at the beginning of the civil rights protests, he wrote a ballad against the use of violence by William Craig, the head of the Black & Tans:

Come all ye Ulster loyalists and in full chorus join,

Think on the deeds of Craig’s Dragoons who strike below the groin,

And drink a toast to the truncheon and the armoured water-hose

That mowed a swathe through Civil Rights and spat on Papish clothes.We’ve gerrymandered Derry but Croppy won’t lie down,

He calls himself a citizen and wants votes in the town.

But that Saturday in Duke Street we slipped the velvet glove—

The iron hand of Craig’s Dragoons soon crunched a croppy dove….O William Craig, you are our love, our lily and our sash.

You have the boys who fear no noise, who’ll batter and who’ll bash.

They’ll cordon and they’ll baton- charge, they’ll silence protest tunes,

They are the hounds of Ulster, boys, sweet William Craig’s dragoons.6

Stirring stuff. One can almost smell the rain on the Aran sweaters of the protesters who would have sung it. And I do hope that when Heaney produces his collected poems he will allow us to see more of his work in that vein, including the song he wrote after Bloody Sunday in Derry, January 30, 1972, which has apparently never seen the light of day. But the point was that times changed, changed and grew worse, until to write that sort of stirring stuff was no longer an option.

Here is Heaney, in his Nobel address, published as Crediting Poetry, looking back on the days of internment:

I remember…shocking myself with a thought I had about [a] friend who was imprisoned in the Seventies on suspicion of having been involved with a political murder; I shocked myself by thinking that even if he were guilty, he might still perhaps be helping the future to be born, breaking the repressive forms and liberating new potential in the only way that worked, namely the violent way—which therefore became, by extension, the right way. It was like a moment of exposure to interstellar cold, a reminder of the scary element, both inner and outer, in which human beings must envisage and conduct their lives. But it was only a moment.

Only a moment, and if it was the only such moment then Heaney was lucky, since the situation was such as to provoke many such moments in many such people. And Heaney chooses to describe this particular moment immediately after recounting that unforgettable, one hates to say classic, story of the recent Troubles. Here it is as he tells it:

One of the most harrowing moments in the whole history of the harrowing of the heart in Northern Ireland came when a minibus full of workers being driven home one January evening in 1976 was held up by armed and masked men and the occupants of the van ordered at gunpoint to line up at the side of the road. Then one of the masked executioners said to them, “Any Catholics among you, step out here.” As it happened, this particular group, with one exception, were all Protestants, so the presumption must have been that the masked men were Protestant paramilitaries about to carry out a tit-for-tat sectarian killing of the Catholic as the odd man out, the one who would have been presumed to be in sympathy with the IRA and all its actions. It was a terrible moment for him, caught between dread and witness, but he did make a motion to step forward. Then, the story goes, in that split second of decision, and in the relative cover of the winter evening darkness, he felt the hand of the Protestant worker next to him take his hand and squeeze it in a signal that said no, don’t move, we’ll not betray you, nobody need know what faith or party you belong to. All in vain, however, for the man stepped out of the line; but instead of finding a gun at his temple, he was pushed away as the gunmen opened fire on those remaining in the line, for these were not Protestant terrorists but members, presumably, of the Provisional IRA.

In that same Oxford lecture which I have already quoted from, Heaney describes his mixed feelings of guilt at attending a formal dinner in Oxford in May 1981 at the time that Bobby Sands, the IRA hunger striker, had just died. Sands’s family had been friendly with the Heaneys, and though he would not, had he been in Ireland at the time, have joined Bobby Sands’s wake, yet he still felt it was a betrayal to be enjoying such hospitality at such a time. He was in, he said, “the classic bind of all Northern Ireland’s constitutional nationalists,” since his cultural and political ideals were “fundamentally Ireland-centred,” but at the same time he was always obliged to distinguish his aims from the means used by the IRA. And he compares his position, very properly, to that of John Hume (another Irishman deserving of a Nobel), who may well today be generally credited with brokering the recent ceasefire, whatever its current ambiguous state.

The difference is, of course, that Hume’s work has kept him largely on a shuttle between Ulster and London, while Heaney’s procedure has been parabolic: from Belfast and Dublin via County Wicklow, from Ulster to Stockholm via California and Harvard—rather in the manner of the Voznesensky poem in which Gauguin, in order to get from Montmartre to the Louvre, makes a detour through Java, Tahiti, and the Marquesas. And just as it turned out recently that one part of the solution to the Ulster peace process (assuming that that is what it is) lay in the United States, so it has turned out, for Heaney, that an important part of his becoming a major Irish poet took place in the environs of Harvard Yard. Engagement and flight—the twin subjects of “The Flight Path,” the recent poem already quoted—have been simultaneously necessary for him.

He often writes of the dissident poets of Russia, calling himself an inner émigré, in comparison with Mandelstam. It is an analogy boldly made, which works only in certain senses of the metaphor. That Heaney felt under unbearable pressure at times in Ireland, we can easily believe—but it would not have been a pressure from either government or party. I could imagine it, though, in either Belfast or in Dublin, as a ghastly encouragement of something false, an egging on to make your poetry instrumental. The problem would not be censorship or suppression. It would feel, rather, like an insistent urging not to let people down in their (improper) expectations.

Again and again in Heaney you will find him returning to the myth of Orpheus. In the Nobel lecture he tells us that the day before his prize was announced he was sketching a votive relief, in the small museum in Sparta, in which Orpheus charms the beasts. But it is not only Orpheus the exerter of the magic power of music that draws Heaney to the myth. Not long ago I heard him read his translation of Ovid’s account of Orpheus being torn to pieces—and what came across most vividly was that he was utterly outraged that Orpheus (as if this had happened yesterday) had been torn to pieces.

Perhaps the feeling is that if you possess that power, you are going to have to pay for it. Certainly he possesses that power. I went to the reading he gave in Oxford, with Ted Hughes, at the end of his professorship and thought it the most exciting reading I had heard. It was exciting before it began, and it just went on from there. And now, with his new collection, The Spirit Level, he keeps up the provision of pleasure.

I don’t feel obliged to take all of Heaney (for instance, I like part two better than part one of North; my loss, no doubt, but I don’t much care for what he fishes out of bogs). I didn’t like what I conceived to be writing as if living under an Eastern European censorship. But 1989 seems to have put a stop to all that.

The poem which provides the title for the new collection, “The Errand,” arrived in proof form with an erratum slip. Originally it had read simply:

“On you go now! Run, son, like the devil

And tell your mother to try

To find me a bubble for the spirit level

And a new knot for this tie.”

It’s an evocation of one of those paradoxical injunctions that adults used to give to children, teasing their intelligence with an impossible order. A drearier form was “Go and ask for a long stand.” You were supposed to go down to the shop and say, “Can I have a long stand please?” and they would keep you standing until you got the joke.

I guess Heaney had thought that the idea of finding a bubble for the spirit level was a good metaphor for writing a poem, and that, having written the single stanza, he was under the impression that the poem was finished. But then he realized that the pleasure he was getting from the memory these lines evoked was all the more intense because of what was still going on inside his head, which the rest of us would not be able to intuit. The poem was, in other words, only half written. So he added:

But still he was glad, I know, when I stood my ground,

Putting it up to him

With a smile that trumped his smile and his fool’s errand,

Waiting for the next move in the game.

The erratum slip was inserted and uncorrected proofs dispatched. I shan’t be selling my copy in a hurry, because there is a great delight in seeing the way the whole meaning of the poem shifts. Now it is about father and son, the father taking pride in the son’s refusal to obey a nonsensical order, even as the son is foxed over what to do next. The notion of finding the bubble for the spirit level as finding the way to write the next poem has disappeared from sight. It is visible only in the title of the collection.

And here’s a poem which went straight into my personal anthology of the best of Heaney. It is called “The Butter-Print”:

Who carved on the butter-print’s round open face

A cross-hatched head of rye, all jags and bristles?

Why should soft butter bear that sharp device

As if its breast were scored with slivered glass?When I was small I swallowed an awn of rye.

My throat was like standing crop probed by a scythe.

I felt the edge slide and the point stick deep

Until, when I coughed and coughed and coughed it up,My breathing came dawn-cold, so clear and sudden

I might have been inhaling airs from heaven

Where healed and martyred Agatha stares down

At the relic knife as I stared at the awn.

“The pleasure and surprise of poetry,” says Heaney, is “a matter of angelic potential” and “a motion of the soul.” When I look at a poem like this for the first time, I ask myself: How did it do that? How did we get from the butter-print to heaven and back down to the “awn” so quickly? It’s like watching the three-card trick in Oxford Street. Suddenly the table is folded up under the arm and the trickster vanishes into the crowd—excepting that, when you tap your pocket, you find you have something valuable you could have sworn wasn’t there just a moment before.

This Issue

July 11, 1996

-

1

Seamus Heaney, An Open Letter, Field Day Pamphlet #2 (Derry: Field Day Theatre Company, 1983).

↩ -

2

Blake Morrison, Seamus Heaney (London: Methuen, 1982).

↩ -

3

The New York Review, March 6, 1980, p. 16.

↩ -

4

“The Trouble with Seamus,” reprinted in Elmer Andrews, editor, Seamus Heaney: A Collection of Critical Essays (St. Martin’s, 1990), p. 39.

↩ -

5

“Escaped from the Massacre?” in The Honest Ulsterman (Winter 1975).

↩ -

6

“Craig’s Dragoons,” as quoted in Neil Corcoran, Seamus Heaney (London: Faber, 1986), pp. 26-27.

↩