Santayana’s warning that those who forget the past are condemned to repeat it has become a stock cliché of political criticism. But what about those who remember the past all too well yet choose to repeat its mistakes nonetheless?

One of the more remarkable developments of the 1996 presidential campaign has been the resurrection of a call for a large across-the-board tax cut, a plan once again justified by “supply-side economics.” Sixteen years ago Ronald Reagan endorsed the proposal, introduced by then-Congressman Jack Kemp and Senator William Roth, for an across-the-board 30 percent reduction in personal income tax rates. Mr. Reagan continued to advocate this idea after taking office; and that summer Congress voted to cut rates by 25 percent in three steps. Of course a lesson one might draw from this earlier episode is that proposing an across-the-board tax cut helps get a candidate elected president; but in retrospect it is hard to believe that Mr. Reagan defeated Jimmy Carter just because he had endorsed the Kemp-Roth plan.

The more compelling lesson to be drawn from the tax cut and what happened afterward is not political but economic. In conjunction with the Reagan administration’s other tax and spending policies, the Kemp-Roth tax cut led to record-size budget deficits and borrowing, higher real interest rates, and reduced investment in new factories and machinery. US productivity growth was also disappointing despite several favorable developments—such as falling energy prices and the increasing experience of American workers—that should have boosted it. That experiment from fifteen years ago, moreover, has left behind a legacy of swollen government debt, a shrunken capital stock, depressed productivity and real wages, and a large net balance that we now owe to foreigners in place of the balance foreigners used to owe to us.

Remarkably, Bob Dole has now proposed that we try a similar gamble once again. Almost simultaneously with his selection of Jack Kemp as his running mate in August, Mr. Dole called for a 15 percent across-the-board reduction in personal income tax rates. Since then he has made the tax cut proposal central to his election campaign. Is there serious reason to think that an experiment that failed in the 1980s would work differently today? And what, aside from his opposition to cutting tax rates by 15 percent, is President Clinton offering as an alternative?

Apart from the obvious fact that nobody likes paying taxes, a sizeable tax cut is especially appealing for many Americans today. During the last two decades, the real incomes of most families in our country have stagnated, and the real wages of most working Americans have declined. Last year a family just at the middle of the US income distribution earned $40,600. Despite the healthy increase both last year and the year before, the median US family income was still almost unchanged from twenty years earlier after allowing for inflation.

The average family with $40,600 in gross income has taxable income of about $24,400 after all exemptions and deductions, and pays about $3,600 in federal income tax at today’s rates. Social Security and other taxes take about the same amount. A 15 percent cut in income tax rates would boost the family’s after-tax income by about $540, or from $33,400 to nearly $34,000. For people who realize that they are barely earning today what their parents earned in real terms twenty years ago, even though two people may be at work now where one worked then, an extra $540 would certainly be welcome.

But if we ask how well-off people will be twenty years from now, compared to today, the fact that a tax cut would increase the typical family’s current cash in hand by this amount is far less important than how it would affect the economy’s long-term growth prospects. Federal tax and spending policies can, and often do, have a profound influence on the economy’s ability to achieve productivity gains and thereby provide real increases in wages and incomes. As most people have already recognized, it is by those effects that we should judge whether any particular set of budget proposals would make good public policy.

In assessing the Dole-Kemp proposals, two such effects are especially important. First, people respond to incentives. If they will receive more pay for doing so, most people are more willing to work additional hours, or take an extra job, or accept a promotion even when that means relocating their families. And when they consider such decisions, most people know that when less of their wage is lost in taxes the effect is exactly the same as a raise in before-tax pay. Similarly, most businesses, if they see an enhanced prospect for profit, are more likely to build a new factory, or modernize an existing plant, or spend money to train their employees. Incentives matter, and taxes affect incentives. From this perspective, the lower the taxes the better.

Advertisement

Second, the relationship between taxes and what the government spends is also important, mostly because the borrowing the government has to do to finance its budget deficit will often have the effect of crowding out private investment. Government borrowing absorbs saving that would otherwise be available to finance the investment in new factories and machinery that would make US workers more productive, or would add new homes to house our growing population, or would even make a down payment on our collective debt to foreign lenders. The larger the government’s deficit, the more it borrows, and the less of our scarce saving is available for private businesses and individuals to invest for any of these useful purposes. From this perspective, the smaller the deficit the better.

Reconciling these two goals has become the central tension of fiscal policy in almost all modern industrialized economies. Of course the desire to have both low taxes and a small deficit would create no difficulty if nobody cared about the benefits of government spending. But people do care—about defense, about law enforcement, about income support and medical care for the elderly, about air traffic control, about scientific research and space exploration, about interstate highways and disaster relief, about disease control and national parks and hurricane tracking. And so the tension is real. That most taxpayers can readily identify government programs that do not benefit them personally, and that they therefore would not miss were they to be eliminated, is of little help.

1.

The central point of the Dole-Kemp “Plan for Economic Growth” is the proposed 15 percent across-the-board reduction in personal income tax rates. In their book Trusting the People and their campaign position paper “Restoring the American Dream,” Mr. Dole and Mr. Kemp have estimated that this reduction would lower federal tax revenues, compared to what the government would receive at current rates, by $406 billion over the six fiscal years 1997-2002, and that the other Dole-Kemp tax cut proposals add up to a further $142 billion in reduced revenues.1 These other proposals include a tax credit of $500 for children under age nineteen, expanded Individual Retirement Accounts, lowering the maximum capital gains tax rate to 14 percent (it is now 28 percent), and making more of Social Security benefits tax-free for taxpayers earning more than $44,000 per year.

Because the Dole-Kemp plan would phase in the 15 percent rate reduction in three steps, the six-year total estimated reduction in federal revenues of $406 billion over six years, compared to what would be collected under current rates—or a total of $548 billion when we include the other proposed cuts—is not the best measure of what tax reduction on this scale implies. On average, during fiscal years 2000-2002, once the three-step rate cut was fully in place, the estimated effect of all of the Dole-Kemp tax proposals would be to reduce government revenues, from what they would be at current rates, by an average of $126 billion each year. After 2002, the gap between tax revenues under the Dole-Kemp plan and revenues under current tax rates would continue to widen as taxable income and profits grew.

Public discussion of the Dole-Kemp plan thus far, including much-publicized statements by Nobel Prize-winning economists on both political sides, has mostly concentrated on its claim (1) that its combination of tax cuts, deregulation, and freedom from lawsuits would increase the average pace of real economic growth beyond the modest 2.2 percent per year assumed by the Congressional Budget Office and (2) that between 1997 and 2002 such faster growth would generate additional tax revenues of $147 billion, thereby offsetting about one fourth of the proposed tax cut. The contrast between this claim and that made for the Kemp-Roth tax cut fifteen years ago—when President Reagan himself stated that the tax cut would so stimulate economic growth as to make the deficit smaller rather than larger—is a reassuring sign of progress in understanding. Even so, there is ample ground for questioning whether even these scaled-down estimates may be still too optimistic.

The principal source of doubt is simply that an across-the-board personal income tax cut—that is, a tax cut not aimed at any specific activity—is a very blunt instrument with which to stimulate work, or saving, or investment. The Dole-Kemp proposal does not reduce taxes specifically for workers who take on additional jobs, or firms that hire new workers or build new factories. It simply lowers each family’s or individual taxpayer’s rates.

Nearly three fourths of Americans who pay federal income taxes are in the 15 percent bracket, and most of the rest are in the 28 percent bracket. (For the most recent year for which complete tax return data are available, only 11 percent of married couples and just 4 percent of single individuals reported enough income to be in a bracket higher than 28 percent.) If we include an additional 6.2 percent for Social Security, 1.45 percent for federal health insurance, and an average of 3 percent for state income tax, someone in the 15 percent federal bracket faces about a 26 percent overall “marginal tax rate”—i.e., the rate paid on each additional dollar of income—and hence gets to keep 74 cents out of each additional dollar earned.

Advertisement

Under the Dole-Kemp proposal, the federal income tax rate of those now in the 15 percent bracket would fall to 12.75 percent and the overall marginal tax rate to 23.75 percent, thereby boosting the take-home share of any additional dollar earned from today’s 74 cents to 76.25 cents—a net gain of about 3 percent. That 3 percent gain would of course be welcome, but it is far-fetched to claim that it would be a large incentive spurring people to work harder or save more.

The story is not all that different for taxpayers in the 28 percent bracket. For the great majority, who earn less than $61,200 per person and therefore must pay Social Security tax on all their earnings, the overall marginal tax rate (including the 28 percent federal income tax plus Social Security, federal health insurance, and state income tax) is about 39 percent. The Dole-Kemp proposal would cut the 28 percent federal income tax rate to 23.8 percent and the overall marginal tax rate to 34.8 percent. Doing so would raise the take-home share of an additional dollar earned from 61 cents to 65.2 cents—an increase of not quite 7 percent. Even for taxpayers in the 31 percent bracket, the equivalent increase is still barely 7 percent. These higher-income taxpayers would of course enjoy their 7 percent gain even more than those with lower incomes would enjoy their 3 percent gain; but it again stretches the imagination to suppose that the additional work effort, or saving, or investment induced by this modest incentive would have a large impact on the economy’s overall growth.

For the small proportion of upper-income Americans who currently pay taxes at either the 36 percent rate or the 39.6 percent rate, the story becomes more interesting. For those in the 36 percent bracket (with taxable income, after all deductions, greater than $143,600 for married couples last year), a 15 percent rate cut would boost the take-home share of an additional dollar earned by 9 percent. For those in the 39.6 percent bracket (with taxable income greater than $256,500), the gain would be almost 11 percent.

These larger gains plausibly provide more of an incentive than the increases in take-home pay that most taxpayers would receive. Even so, they are small compared to the tax changes enacted under President Reagan, which reduced the marginal rate paid by America’s highest earners from 50 percent (70 percent on interest and dividends) to 28 percent. And we know in retrospect that even those much larger rate cuts failed to stimulate the “supply side” surge either in work, or savings, or investment that their advocates had promised.

From a broad economic perspective, questions like these about the incentive effects that would or would not be induced by the tax cuts in the Dole-Kemp proposal are very much to the point. From a budgetary standpoint, however, whether or not the proposed package would stimulate sufficient economic growth to generate the $147 billion of additional tax revenues claimed over six years—i.e., about one fourth of the size of the proposed tax cut—is really misplaced. Whether faster growth would produce this amount of extra revenue or perhaps only half as much—indeed, whether any extra growth would result at all—is less important than whether the plan credibly offsets the remaining three fourths of the tax cut.

But here is precisely where the Dole-Kemp plan fails to warrant confidence. Most of the proposal’s budget savings, $136 billion, would reportedly come from unspecified cuts in “non-defense administrative costs” and reductions in unnamed “other spending programs.” The proposal also includes $34 billion that the federal government would receive from a one-time sale of broadcast frequencies. (This is in addition to the $19 billion already anticipated from such sales in last spring’s congressional budget resolution.) For budgetary purposes such sales do offset federal expenditures, and so they would reduce the deficit; but because they absorb the private sector’s saving they act just like deficits in crowding out private investment. Moreover, any revenues that such a one-time sale did provide would not recur to help offset the even larger revenue loss after 2002. (That the sales would actually take place is dubious anyway because most Republicans in Congress have strongly opposed them.) The closest the plan comes to specifying actual spending cuts is to call for reducing the Commerce Department’s budget by $15 billion and the Energy Department’s by $32 billion.

Finally, the Dole-Kemp plan also assumes that the entire, much debated list of spending cuts endorsed by the Republican congressional majority last spring will be passed—including large cuts in Medicare. Most Republican members of Congress voted for these cuts six months ago, but only insofar as they were included in Congress’s annual Budget Resolution. The Republican leadership has never presented legislation cutting specific programs such as Medicare for a yes or no vote; and in the current political atmosphere, we may well doubt whether they can count on their majority to pass such cuts.

The proposal to finance a large tax reduction with mostly unidentified spending cuts, while specifically exempting defense and Social Security, is strikingly reminiscent of the failed Reagan strategy. Then, as now, it would have been possible to cut taxes and yet avoid enlarged deficits by cutting government spending in sufficiently large amounts. But in the 1980s the Reagan administration decided instead to increase military spending, and from its first days in office it ruled expensive domestic programs like Social Security and Medicare “off the table.” Mr. Dole has likewise called for increased military spending, and the Dole-Kemp proposal flatly states that “Medicare, Social Security, and Defense are ‘off-the-table.”‘

Moreover, it will be much harder today than it was fifteen years ago for a new Congress or administration to find other genuine spending cuts to offset a major tax cut. Last year defense, Social Security, Medicare, and interest payments on the national debt accounted for 67 percent of all federal spending. Everything else that the government does added up to only one third of the total. By contrast, in 1980 the three currently “off-the-table” programs, plus interest payments, amounted to only 57 percent of the budget. Even so, President Reagan and the Congress at that time—with a Republican majority in the Senate and a dominant coalition of Republicans and conservative Southern Democrats in the House—failed even to come close to offsetting the Kemp-Roth tax cut by reducing the remaining 43 percent of federal spending.

When Mr. Dole gives most of his proposed spending cuts labels like “cut in non-defense administrative costs” (in “Restoring the American Dream”), or “downsizing administrative and personnel costs” and “program reforms” (in Trusting the People), he is following the Reagan strategy of assuring the American public—or at least those who do not receive welfare assistance—that no one need make sacrifices to finance his proposed tax cuts. Apart from the Energy and Commerce Departments, the “other spending programs” to be cut are unspecified. The Dole plan names no other federal agencies whose funds would be reduced.

No doubt, as Mr. Dole and Mr. Kemp propose, cuts can be made in “administrative costs”; and some of the cuts would affect few others than the bureaucrats who do the administrating. But because payments other than those for defense, Social Security, Medicare, and interest now make up such a small part of what the government spends, it is implausible that genuinely large-scale cuts in expenditures for other purposes would be merely “administrative”; the newly proposed spending cuts by Mr. Dole and Mr. Kemp and the cuts already included in the Budget Resolution passed last spring by the Republican congressional majority add up to 19 percent of all the spending that the government would be doing between 1997 and 2002 under a continuation of current programs. Because of how these cuts are allocated, the average reduction in programs other than entitlements is 27 percent. And each time Mr. Dole exempts a politically sensitive program—as he did for veterans’ benefits when he addressed the Veterans of Foreign Wars convention, or for the Los Alamos and Sandia research labs when he visited New Mexico—the implied average reduction in all other programs becomes greater still.

Reductions on this scale clearly cannot be limited to administrative costs, but no one has yet said what they would involve: Fewer FBI agents? Fewer border patrols? Fewer air traffic controllers? Closing some federal prisons? Shutting some embassies? Ending the space program? To inveigh abstractly against bureaucracy and the government’s use of the taxpayers’ dollars does not help to answer these questions.

Radical cuts in such essential government programs are unlikely to occur for the simple reason that they would mostly be a bad idea if they did; and once they are spelled out most Americans will realize that. (Some of the proposed cuts would even be arithmetically impossible. As former Congressional Budget Office director Robert Reischauer has pointed out, the combination of the cuts already included in last spring’s Budget Resolution and the proposed further $32 billion cut in the Energy Department’s non-defense spending exceeds 100 percent of the department’s non-defense budget.) For just this reason, the “cut in non-defense administrative costs” and “reduction in other spending programs” that Mr. Dole has proposed to finance his tax cut have no more reality than the “future savings to be identified” and the “elimination of fraud, waste, and abuse” that President Reagan offered to finance his. In the end, the outcome would be the same.

Fifteen years ago, the Kemp-Roth tax cut set off a major surge in US consumer spending. Under the circumstances, that impact was welcome. Unemployment reached a postwar record high of almost 11 percent in 1982, and the US was using less than 72 percent of its industrial capacity, a record low. It would have been far better if the tax cut had produced a boom in investment spending, as its advocates had predicted. But with nearly eleven million Americans unemployed, and thousands of factories idle, stimulating consumption helped business to recover. (Indeed, when unemployment is as widespread as it was in 1982 and 1983, tax cuts that stimulate consumption probably help to stimulate investment too. In a severely underemployed economy, the positive influence of stronger demand for business products outweighs the negative effect of higher interest rates caused by enlarged deficits and increased government borrowing.)

Today’s circumstances are different. Although anemic growth in productivity continues to depress wages, unemployment is at a twenty-year low and the proportion of American adults who are working is at an all-time high. The percentage of American industrial capacity being used is also fairly high, as is typical in an economy that is at or approaching full employment. The opportunity to stimulate economic growth (and hence tax revenues) by simply putting people and factories back to work, as the Kemp-Roth tax cut did at first, is therefore highly limited.

The immediate consequences of a large across-the-board tax cut in today’s almost fully employed economy would depend on monetary policy. If the Federal Reserve were to hold short-term interest rates at their current levels, despite increased government borrowing and stronger consumer demand, business would grow faster—for a while—and unemployment would fall still further. That outcome would almost surely lead to renewed price inflation. Because most investors would readily anticipate this faster inflation, long-term interest rates (which the Federal Reserve does not control, but which are crucial for most kinds of investment) would rise. Whether investment would increase or decrease is difficult to know.

This overheated situation would be only temporary, of course. Before long, the Federal Reserve would have to tighten monetary policy, and interest rates, whether short-term or long-term, would rise; business would subside to normal levels, and investment would suffer more than would other kinds of spending. Worse yet, if past experience is an accurate guide, getting inflation back down to today’s modest level would then require a recession. That would mean even tighter monetary policy, even higher interest rates, and an even steeper decline in investment.

For just this reason, the Federal Reserve presumably would not allow a tax cut to set off a new consumption boom in the first place. Instead, the officials in charge of US monetary policy would (and should) raise short-term interest rates at the first clear indication that a surge in consumer spending was emerging. The resulting rise in interest rates, spreading from short-term rates to longer-term rates, would discourage both business investment and homebuilding. Unless countries abroad matched these interest rate increases, higher interest rates here would also increase the foreign exchange value of the dollar and make it harder for American businesses to export their products abroad or compete at home against foreign producers. All this would be simply a repetition of what happened in the 1980s following the Kemp-Roth tax cut, once the economy had returned to full employment.

2.

Just how much the deficit would widen, how far interest rates would rise, and how badly investment would decline under the Dole-Kemp proposal would of course depend on the extent of the failure to offset the tax cut. In the 1980s the deficit averaged 4.1 percent of America’s national income, compared to 0.8 percent in the 1960s and 2.3 percent in the 1970s. (After adjustment to allow for the influence of recessions as well as full employment, the “structural” deficit averaged 3.2 percent in the 1980s versus 1.5 percent and 2.2 percent in the 1960s and 1970s, respectively.) Interest rates on short-term business borrowing rose to 4.26 percent above the US inflation rate on average in the 1980s, compared to 1.85 percent above that rate in the 1960s and 1970s. And net investment in new factories and machinery declined from 3.7 percent of national income on average in the 1960s and 1970s to 2.8 percent in the 1980s.

The government’s deficit for the 1996 fiscal year (which just ended on September 30) was only 1.5 percent of national income, and so far this year real interest rates on business borrowing have averaged 3.3 percent. Net investment data are not yet available for 1996 (or 1995), but gross investment has been sufficiently strong that net investment has no doubt improved as well. Surely no one wants to go back to the experience of the 1980s, whether in the proportional size of the deficit or in the level of real interest rates or in the rate of investment as a share of our overall economy.

Moreover, just as under the Reagan-Kemp-Roth policy, the effects of the Dole-Kemp tax cut would leave their mark long after the initial mistake had been recognized and corrected. Deficits that are incurred year by year do not simply go away but add to the outstanding debt. The government still owes that debt, and still must pay interest on it, even if it succeeds in reducing its current deficit to zero.

Investments in factories and machines made in any year do not simply go away either. They become part of the nation’s stock of productive capital, which businesses can continue to use long after the initial investment is made. But conversely, when investment is inadequate, the result is a capital stock that remains diminished even after yearly investment has recovered to a more satisfactory rate. The risk posed by the Dole-Kemp tax proposal is therefore more than a matter of enlarged deficits and reduced investment over a period of perhaps a few years.

One easy way to see the legacy left behind by misguided and long abandoned budget policies is to consider the interest the US government is still paying on the debt it incurred between 1981 and 1992. That interest accounted for more than all of the government’s deficit for the 1996 fiscal year. The government’s outstanding debt at the beginning of fiscal 1996, after we deduct the amounts held in the government’s own trust funds, was $3.6 trillion. By contrast, the outstanding debt at the beginning of fiscal 1981 (again net of trust fund holdings) was only $710 billion. Most of the difference reflects the fact that the deficits the government incurred between 1981 and 1992 added up to $2.3 trillion. In other words, 63 percent of the entire national debt at the beginning of last year was the result of borrowing in order to finance just those twelve years’ deficits.

According to preliminary estimates by the Congressional Budget Office, the government paid $240 billion in net interest during the last fiscal year, of which 63 percent is $151 billion. But the CBO’s deficit estimate for last year is only $116 billion. If the government had balanced its budget during the twelve years between 1981 and 1992, therefore, last year’s budget would have been in surplus by $35 billion.

We cannot wish away the debt that our government incurred in the years following the Kemp-Roth tax cut. We also cannot wish into existence the factories our businesses did not build during these years of depressed investment, or the machines they did not buy. In recent years the amount of capital per worker in the American economy has grown much more slowly than it did earlier on in the post-World War II era—despite the fact that our labor force has grown more slowly since the baby-boom generation reached adulthood, which should have made it easier to maintain the growth of capital per worker.

At the end of 1992 US business had $62,900 in plant and equipment for every worker employed in the private sector of the economy. If between 1981 and 1992 we had simply kept on devoting to net new investment the same 3.7 percent of our national income that we had invested on average in the 1960s and 1970s, by 1992 our businesses would instead have had $76,000 of capital per worker—a difference of more than 20 percent. Even if we accept conservative estimates of how much physical capital adds to workers’ productivity, a difference of this magnitude does much to explain why American workers’ real wages have declined during this period, and American families’ real incomes have stagnated.

Factories and machines, of course, are not all that matters for workers’ productivity and real wages. If we had been investing especially heavily in education and worker training during these years, or in research and development, perhaps our productivity would have been high even without more plant and equipment. Even within the limited sphere of physical capital, perhaps our productivity would have advanced more rapidly if we had invested large amounts in roads and airports and other elements of our public infrastructure. But in fact we have neglected to make each of these kinds of investment, and our productivity and real wages have suffered accordingly. Under the Dole-Kemp plan, investment in infrastructure and worker training would suffer still more.

Over the six fiscal years between 1997 and 2002, the Dole-Kemp 15 percent across-the-board tax cut would reduce federal revenues by a total of $406 billion according to their own estimate; and all of the tax cuts they propose, taken together, would reduce revenues by $548 billion during the same period. That is, by 2002, the government would have collected $548 billion less than it would have under current tax rates. If output and prices were to rise thereafter at the rates projected by the Congressional Budget Office, the reduction in federal revenue over the subsequent six years would be another $918 billion, for a twelve-year total of $1,466 billion.

At an interest rate of 6.5 percent (an average of today’s prevailing rates on short- and long-term Treasury securities), this amount of extra debt would add $95 billion to the government’s interest payments each year. Even if we take at face value Mr. Dole’s estimate in Trusting the People that faster economic growth induced by these and other proposals would generate sufficient revenues to offset more than one fourth of the revenues lost through these tax reductions, the twelve-year debt total would still be $1,073 billion, and the resulting additional interest payments $70 billion each year.

Whether the government would actually incur this amount of additional debt, or only some fraction of it, would of course depend on whether Congress and the President would in fact cut spending to offset these reduced revenues. But the scale of the potential obligations involved in such a venture makes clear the stakes involved. In principle, the government could sustain any size tax cut and still not run a larger deficit by sufficiently cutting what it spends. Whether it would actually do so—and whether the public would support that action if it did—is another matter.

3.

What is President Clinton offering as an alternative to the Dole-Kemp plan? During the election campaign Mr. Clinton has proposed many new tax and spending initiatives, including, among others, eliminating capital gains taxes on sales of most homes; tax credits for college tuition; more flexible Individual Retirement Accounts; expanded “empowerment zones” to encourage business investment in depressed communities; helping the newly unemployed keep up their health insurance premiums; and funds to enable more schools to connect to the Internet. But implementing these ideas would have only a very small effect on the budget. And while many of these ideas might be good ones, their overall effect on the economy’s growth would be very small as well. For the most part, Mr. Clinton has chosen to run on the economic policies he already had enacted or has announced, implicitly including the budget plan that he proposed, but that Congress did not accept, last spring.

Especially in light of how the Dole-Kemp tax cut would be likely to affect the federal budget, it is important to bear in mind the progress made during Mr. Clinton’s term in narrowing the deficit from the record levels of the Reagan-Bush days. In fiscal year 1992 the deficit was $290 billion, or 4.9 percent of America’s national income. For the fiscal year that just ended, the Congressional Budget Office has estimated that the deficit was $116 billion, or just 1.5 percent of national income—the first time the US government’s deficit has been less than 2 percent of national income since Jimmy Carter was president.

Part of this improvement has resulted from the package of spending cuts (mostly in defense) and tax increases on high-income taxpayers that Congress adopted at President Clinton’s urging three years ago. The rest reflects the improvement in the economy since then. After adjustment to allow for the return to nearly full employment, the decline in the deficit has been only about 2 percent of national income.

For purposes of comparison to the Dole-Kemp proposal, however, the recovery of the economy since 1992 is very much to the point. Contrary to the dire warnings that critics of the 1993 Clinton budget package issued at the time, the increase in income-tax rates for high-income taxpayers did not arrest the economy’s recovery. Nor did it otherwise prevent tax revenues from rising sharply. Fears that high-income taxpayers in particular would somehow “go on strike,” and not work or invest, proved mistaken. (Since 1993 business investment has shown especially strong growth.) Today, conversely, there is little reason to believe that the proposed Dole-Kemp tax reduction, which would mostly benefit high-income taxpayers, would dramatically stimulate economic growth or otherwise prevent tax revenues from falling far short of what they would be at current rates.

The narrowing of the government’s deficit over the last four years is a major accomplishment, for which Mr. Clinton can take much of the credit. But as most budget analysts in and out of government agree, under current tax and spending policies the deficit will widen almost continually from now on. Ten-year “baseline” projections by the Congressional Budget Office show revenues increasing by 54 percent versus a 68 percent increase in total spending between now and 2006. As has often been pointed out, much of this increase will be for entitlements, especially Medicare and Medicaid, each of which will more than double in cost during the coming decade. The challenge today is to change current policies so as to keep the deficit shrinking and not allow it to grow as a result of those rising costs.

A year ago, President Clinton agreed to legislation requiring him to submit a tax and spending plan that would lead to a balanced budget by 2002, as evaluated by the Congressional Budget Office. He agreed as well to base this projection on the CBO’s own economic assumptions (which at that time were less optimistic than the administration’s). Mr. Clinton’s first plan failed to meet this test; but after the administration revised it, the CBO certified that Mr. Clinton’s plan, like the Republican congressional proposal, indeed delivered a budget that would realistically be in balance by 2002.

In fact, at first glance the President’s plan looks not all that different from the congressional Republicans’. While their plan offers a tax credit for children up to age eighteen in families earning up to $150,000, his offers a credit for children up to age twelve in families earning up to $75,000. While theirs would cut Medicare by $158 billion and Medicaid by $72 billion over six years, his would cut Medicare by $116 billion (including “contingency provisions”) and Medicaid by $54 billion. While their plan proposed to save $53 billion through welfare reform, his proposed saving $38 billion. While theirs proposed to cut discretionary spending by $305 billion, his proposed $228 billion. These differences do not suggest deep disagreements over federal budget policy.

The real differences are twofold. First, the Republican plan, even without the Dole-Kemp 15 percent tax cut, would significantly lower taxes; and Mr. Clinton’s would not. It is true that Mr. Clinton promises “middle-class tax relief” amounting to $129 billion in tax cuts over six years and that this exceeds the $112 billion cut in taxes over the same period envisaged in the Republican plan. But in fact the Clinton plan would cut some taxes and increase others so as to leave the total amount of revenue nearly intact after the tax cuts are made.

Mr. Clinton would increase revenues $36 billion over six years by re-imposing some recently expired excise taxes, like the airport ticket tax, and he would raise another $54 billion through changes in corporate income taxes by closing loopholes the administration finds objectionable. The effect is to trim the plan’s net tax cut to just $38 billion. The Clinton plan includes further “contingency” tax increases to be imposed only if the plan, as enacted, does not result in sufficient deficit narrowing by 2000 to make a balanced budget likely in 2002. The CBO estimates that the likely trajectory of the deficit under the Clinton plan would trigger these further tax increases; and they would add up to another $32 billion in 2001 and 2002. Hence the Clinton plan would cut taxes by just $6 billion over the six years between 1997 and 2002, and not at all after 2002.

The second key difference between the Clinton plan and the congressional Republican plan, which does not show up in the budget estimates at all, concerns the different ways each plan would achieve its planned savings in Medicaid and especially in Medicare. The Clinton approach would preserve the universal coverage of elderly Americans under the Medicare program, achieving savings mostly by further tightening the reimbursement rates to hospitals and physicians. The Republican approach would instead give elderly citizens the option of receiving subsidies that they could use for purchasing private health insurance if they choose—and are able—to do so.

Congressional Republicans object that the cost savings promised by the administration are suspect. The administration objects that the Republican plan would ultimately gut Medicare, leaving a program with mostly high-cost patients unable to get insurance in the private market. Both criticisms are probably valid. In the end, it was differences like these over broad issues of public policy, more than disagreements over specific tax and spending totals, that prevented President Clinton and the Republican majority in Congress from reaching a budget agreement last spring.

A further difference, which might also have acted as an obstacle to agreement but on which Mr. Clinton gave way, was welfare reform. The welfare bill that the President signed last month brought to an end the open-ended guarantee of assistance for eligible indigents that was first enacted in 1936. The individual states will continue to administer the Aid to Families with Dependent Children program, as they have in the past, but henceforth the federal government will fund AFDC with a fixed-sum “block grant,” not an open commitment to support all eligible families. Moreover, each family will face a lifetime limit of five years of eligibility. Other cost-saving measures include allowing able-bodied non-elderly adults to receive food stamps for no more than three months in any three-year period, and eliminating the eligibility of non-citizens (including legal immigrants waiting to become citizens) for all means-tested entitlements.

As the sharp public debate over this issue has made clear, the bill that the President signed poses a great many difficult problems. No one knows how states will enforce provisions like the five-year eligibility limit. Some of the projected savings will probably not materialize—for example, many non-citizens will now become American citizens—and some part of the rest will now be a cost to the states. Ironically, those who advocated this kind of welfare reform have shown little interest in providing job training or transportation assistance, much less job creation programs, to help move people from welfare to work. As James Q. Wilson, a respected conservative who is hardly a defender of the status quo in welfare policy, recently put it:

The great risk is that competition among the states for low tax rates and small welfare loads, coupled with our ignorance as to how to get large numbers of mothers off the program, will hurt children who never asked to be born into a welfare world.2

But these are questions of social policy, not budget policy. The bill that has now become law is very close to the original Republican proposal and very unlike the President’s. But the budgetary difference—$54 billion in savings over six years under the Republican bill versus $38 billion under the Clinton plan—was never very large. By giving way on this legislation, Mr. Clinton has removed it not only as a campaign issue but as a possible impediment to reaching a budget agreement. In retrospect, no one should have any illusions that the central disputes concerning welfare reform were over saving money.

One echo of the welfare debate that does remain at issue is the difference in how Mr. Clinton’s proposal for a $500 per child tax credit and the Republicans’ parallel proposal would affect the working poor. Because people who earn no income pay no income tax, of course neither proposal would benefit the poorest families. But because the Republican plan (at least as now spelled out by Mr. Dole) would allow families with low incomes to take advantage of the child credit only to the extent that they still owed tax after using the Earned Income Tax Credit, while the Clinton child credit applies to tax owed before using the EITC, their effects on the working poor would be quite different.

Robert Greenstein, of the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, has estimated that 28 million children, or 40 percent of all children in the country, are in families that have too little income to receive any benefit at all from Mr. Dole’s tax credit, and another 6 percent would receive only partial benefit. (Only 5 percent of the nation’s children are in families that would not benefit because their incomes are too high.) It is little wonder that the examples Mr. Dole and Mr. Kemp use to show how families would benefit from their tax plan, in Trusting the People, begin at family income of $30,000. By contrast, Clinton’s proposal would benefit many more families at the bottom of the income scale, because of the difference in how the child credit interacts with the EITC, and it excludes many more at the top because the upper limit on family income for receiving the child tax credit is $75,000 instead of Mr. Dole’s $150,000.

In principle, Mr. Clinton’s six-year budget plan remains before Congress, as does the plan contained in the Budget Resolution passed by the Republican majority last spring. Neither side, however, now seems to have much interest in resolving the differences before the election. Instead, the Clinton administration and the Congress agreed on a one-year budget for fiscal year 1997, without taking up any major new tax legislation. In light of the few real differences between the President’s six-year plan and the congressional Republicans’ plan so far as the size of the budget is concerned, continuing on in this way until after the voters have had their say probably makes little difference.

The gulf between the Clinton plan and the new Dole-Kemp plan, however, is far wider. The Dole-Kemp plan would cut taxes between 1997 and 2002 by $548 billion, not the $112 billion that the congressional Republicans had previously proposed. And, to the extent that the spending cuts it offers are real, it would add another $217 billion even beyond the six-year reduction in spending already envisaged by the congressional Republicans. Especially compared to the more modest Clinton plan, the differences are very large indeed.

But the most serious difference of all is that, whatever its flaws, the Clinton plan has a good chance of preserving and even extending the progress made over the last four years in narrowing the government’s deficit, and thereby fostering advances in investment and productivity and real wages in the years ahead. The Dole-Kemp proposal would almost certainly widen the deficit instead.

A large across-the-board tax cut that is not matched by credible spending cuts is a mistake we should not repeat. In light of past experience, it is astonishing that Mr. Dole would make this proposal. But he has, and as a result whether or not we shall make the same mistake twice has become the central economic issue in this year’s election.

—October 3, 1996

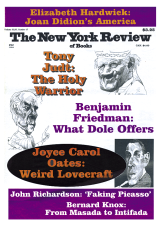

This Issue

October 31, 1996

-

1

Bob Dole and Jack Kemp, Trusting the People: The Dole-Kemp Plan to Free the Economy and Create a Better America (HarperCollins, 1996); “Restoring the American Dream” (Dole for President, Inc., August 5, 1996).

↩ -

2

“But who will find them work?” Times Literary Supplement, September 20, 1996, p. 15.

↩