1. In his new book about saving Social Security, Restoring Hope in

America, the writer Sam Beard, an inner-city organizer turned fiscal conservative, indulges in a few tricks of the political pamphleteer’s trade. “It’s time to stop relying on government for handouts. It’s time to break the bonds of dependence on Washington,” he tells us. “There’s a better way. We are a prosperous, industrious nation, and we are capable of instituting a plan that can—quite literally—turn every hard-working American into a millionaire.”

Beard wants us to believe, of course, that it is government that is holding us all back. Forty-five years from now, Beard calculates, an average worker who has invested his Social Security contributions in a privately administered portfolio of stocks and other securities instead of handing it over to the government will become a millionaire twice over—if only in nominal rather than inflation-adjusted dollars. What Beard omits to say is that if Social Security maintains its currently mandated benefits, it will also make the typical recipient a millionaire in forty-five years, without the risk of investing in the volatile stock market. By the year 2040, a typical Social Security beneficiary will receive about $92,000 a year in the dollars of that year, on the basis of assumptions similar to Beard’s. To buy an annuity in that year paying the same annual amount until death would cost nearly $1 million.1 Even today, a package of Social Security and Medicare benefits is worth half a million dollars to the typical retired couple.

Like much of the new literature on the subject, Beard’s book transforms a genuine but soluble problem concerning Social Security’s financing into an ideological crusade. Beard insists that Social Security must be “radically reformed.” Time Magazine entitles its recent cover story on the subject, “The Case for Killing Social Security.” The economist Thomas J. DiLorenzo writes in a short book called Frightening America’s Elderly that “unless changes are made soon, the entire program will collapse by the year 2029.” DiLorenzo doesn’t bother to tell us precisely what he means by collapse. His thesis is that lobbyists have frightened the elderly to the point where they will not entertain constructive reforms of the retirement system. He readily uses fear to promote his own ends, however. One looks through his pamphlet in vain for documentation of Social Security’s coming collapse. Such writers understand that a mere declaration of a coming catastrophe in Social Security is sufficient to frighten a public long made skeptical of government promises by large federal deficits, lost jobs, and two decades of stagnating wages. One survey finds that two out of three Americans aged twenty-five to thirty-four believe it is unlikely that they will receive their Social Security benefits when they retire. Critics of the current system like to point out that more young Americans believe in UFOs than in the security of their public retirement benefits.

Before we take a cooler look at the facts, we should remind ourselves how much has been accomplished by the Social Security system that so many are eager to change. About 90 percent of elderly Americans today receive Social Security benefits, which average about $8,000 per person or $14,000 per couple a year. For 60 percent of these recipients, the benefits make up more than half of their income. The program has reduced the proportion of elderly with incomes below the federally defined poverty line from 35 percent as recently as the mid-1950s to about 12 percent today, i.e., about the same percentage as that among working adults. As a result, millions of the elderly no longer have to live with their middle-aged, middle-class children, who can now presumably devote more resources to their own children and their own lives. Today, the income of 50 percent of the elderly would fall below the poverty line if they did not have Social Security benefits.

One reason Social Security has been so successful in reducing poverty among the elderly is that the system has never been designed to produce the highest feasible financial return on each worker’s contributions. It is not a conventional pension plan but a social program in which taxpayers pay benefits owed to retirees more or less as they come due. Retirement benefits are distributed progressively so that lower-wage earners receive a greater proportion of their lifetime earnings than do higher-wage earners. For example, a worker who has earned half of the nation’s average wage can expect to receive about 56 percent of his or her average earnings in Social Security benefits while the typical earner would receive only about 42 percent of his average income and the high-wage earner only 28 percent. Other important benefits of the program are apparently easily forgotten or have come to be taken for granted. For example, 98 percent of all children whose working parents die receive a cash benefit averaging $700 a month. And all of this is accomplished with administrative costs that come to less than a penny per dollar of benefits. The often-praised private social security system in Chile costs a minimum of 15 cents to administer for every dollar of benefits.

Advertisement

Is this a system bound to collapse? Certainly there is much to worry about. In twenty-five to thirty-five years we can expect a significant shortfall in the funds needed to meet Social Security obligations. The two reasons for this have been widely discussed. First, as the baby boomers born in the 1940s and 1950s retire, beginning in about fifteen years, too few workers will be available to pay Social Security contributions to support the swelling number of retirees. In 1960, there were five workers for every retiree. This ratio will fall to three to one in 2020 and, after the baby boomers are nearly fully retired in 2030, to less than two per retiree. Second, and more important over the long run, life expectancies of the elderly are rising rapidly, which requires that Social Security payments be significantly extended.

Nevertheless, according to current projections, the Social Security taxes paid by baby boomers who will still be working in large numbers, plus interest income on assets, will be sufficient not only to meet Social Security’s obligations until 2019 but also to accumulate assets in the trust fund that will total $3.3 trillion. After that, in 2020, however, obligations in nominal dollars will begin to exceed the income from Social Security taxes by roughly $200 to $300 billion a year. The accumulated $3.3 trillion trust fund could theoretically be tapped at this point to meet Social Security obligations until 2029. But critics are persuasive in pointing out that it is unlikely that any such mountain of money will be available. The federal government is already borrowing from the trust fund to meet current needs, and if Social Security payments continue at the current rate, it will likely continue to do so.

Beginning in 2020, the federal government will have to make up for the spent portion of the $3.3 trillion by borrowing the money in the open market or raising taxes, if the fund is completely depleted, by an average of more than $300 billion a year over the decade in order to meet Social Security obligations. If we adjust for inflation, the amount needed comes very roughly to an average of $150 billion or so a year, about the size of the entire federal deficit today. The Social Security deficits will continue indefinitely.

What may surprise many who have been alarmed by the situation, however, is that even if the shortfall is allowed to occur, Social Security taxes will still be sufficient to meet 75 percent of the mandated benefits for seventy-five years. This would cause great hardship but it is not exactly a collapse of the system. It is also true that the expected shortfall could be entirely eliminated if Social Security taxes are raised today by about 2.2 percent. (Social Security payroll taxes currently equal 12.4 percent of payroll, split equally between employers and employees.) Such a tax increase would cost the average worker about $240 a year in addition to the current Social Security tax of about $1500, and would cost that worker’s employer another $240 a year. Provided the revenues are not diverted by the federal government for other expenditures, the 2.2 percent increase would make the system solvent for another seventy-five years. 2

Still, a 2.2 percent hike in Social Security payments is probably not politically practical in view of the deep public resistance to paying higher taxes; nor is it likely that the government would keep its hands off the additional buildup in trust fund assets that would result from such an increase between now and 2019. But there are less painful ways to meet the expected shortfall in Social Security funds while at the same time keeping to a minimum any buildup in the trust fund that Washington would likely squander. Nor would they require a significant reduction in the annual Cost of Living Adjustment for Social Security benefits that is so widely and rather flippantly discussed.3 An impressive book of analyses by experts on the subject, Social Security in the Twenty-First Century, edited by Eric R. Kingson of Boston College and James H. Shulz of Brandeis University, presents several moderate plans to insure that the Social Security revenues will be adequate to continue payments. Most of these proposals include a combination of modest reductions in benefits and revenue-raising measures such as a graduated tax increase or plans to invest trust fund assets in common stocks. They thus would have the effect of spreading the sacrifice among beneficiaries, taxpayers, and investors.

Robert J. Myers, the former chief actuary of Social Security, for example, suggests raising the retirement age gradually to seventy (it is already being raised from sixty-five to sixty-seven). This alone would reduce the anticipated Social Security deficit by about half. To make up the rest, he proposes a tax increase of one percentage point to take effect gradually beginning in 2015, and to be allocated equally between employers and employees.

Advertisement

Robert M. Ball, the former commissioner of Social Security, presents a different plan that would require a more modest reduction in benefits. He suggests incorporating the nearly four million government workers not now covered by Social Security into the system. This would raise contributions significantly more than it would increase expenditures on benefits. Ball also suggests imposing income taxes on benefits that exceed an employee’s contributions as well as changing slightly the basis on which lifetime income is computed. These three reforms, plus one or two others, would cut the expected deficit by well over half. The rest could be eliminated by a small hike in the Social Security tax, or, as we shall see, investing a portion of trust fund assets in common stocks. Both Meyers’s and Ball’s plans would make Social Security solvent for another seventy-five years, and minimize the danger of building up a phantom trust fund. The loss of this fund could prove the biggest political obstacle to adopting such plans, because both the Democrats and Republicans plan to use the trust fund to help balance the federal budget in coming years.

2.

Unfortunately, solvency is not the only problem Social Security will face in the future. Will America Grow Up Before It Grows Old? by the investment banker and former Commerce Secretary Peter G. Peterson, uses some of the same rhetoric as do other alarmist critics of the Social Security system; and he does not adequately consider the more moderate answers to the solvency question I have just mentioned. But he does have a view of several other consequences of an aging America that could threaten Social Security and the US economy in general, consequences that some of the reformers who concentrate narrowly on Social Security too often ignore. This larger picture includes the need not only to finance retirement benefits but also, as well we shall see, to shift public spending—from consumption to investment—as well as to limit mounting costs of medical care. Such comprehensive analyses cannot simply be dismissed.

For one thing, the US will have to deal with a deficit in the funding of Medicare that will ultimately exceed Social Security’s expected deficit in the next century. Peterson contends that it is ingenuous at best to believe the nation will be able to afford both. Michael D. Hurd of the State University of New York at Stony Brook agrees with this point of view. In another of the fine contributions to Social Security in the Twenty-First Century, Hurd estimates that, as a percentage of Gross Domestic Product (GDP), Medicare’s costs will more than triple from 2.53 percent in 1999 to 8.63 percent in 2040, while Social Security outlays will rise from 4.83 percent in 1994 to 6.66 percent in 2040. In total, then, Social Security and Medicare could absorb more than 12 percent of the nation’s GDP in 2020 and more than 15 percent in 2040. (Together, they absorb about 8 percent of GDP today.) Others estimate that taxes would have to rise to 25 percent to 30 percent of wages to fund both programs unless changes are made.

Peterson also argues that the US must divert funds from consumption programs such as Social Security toward government investment in research and development, early education, and job training, among other public programs, as well as toward balancing the federal budget. He would, in fact, prefer to see the federal budget have a surplus of revenue over expenditures to try to raise the nation’s pool of savings. Peterson has long warned the country about its low savings rate. But one does not have to sympathize completely with his passionate dedication to balancing the budget—his new book includes a proposal for a constitutional amendment to do so—to agree that the nation must increasingly shift government spending from consumption programs to long-term investment in order to raise the nation’s productivity.

In my view, and apparently in Peterson’s as well, public investment in infrastructure, research and development, education, and training can raise labor productivity, or output per hour of work, which has grown at less than half its historical rate for twenty-three years. This slow increase in productivity is the underlying cause of the nation’s torpid economic growth since the early 1970s, as well as of its stagnating standard of living. Peterson would demand that legislation for public investment programs include a “productivity statement” showing how they can improve the nation’s output per hour. This seems to me an excellent proposal; but I would expand the requirement to all major federal programs, including military spending (which would fare poorly).

Another widely shared concern of Peterson’s is that Social Security has become a poor investment for current workers, with results that are especially unfair to younger Americans. The ratio of Social Security benefits to taxes paid has in fact fallen significantly since the 1950s. It has done so, again, because of the ineluctable rise in the number of retirees per active worker, which has required substantial increases in Social Security taxes to pay for benefits that can no longer be raised more quickly than the cost of living. Studies cited in Social Security in the Twenty-First Century show that workers who retired in the 1960s, for example, have been receiving an average return of more than 12 percent a year on their contributions, adjusted for inflation. Those who retired in the 1980s have been receiving a return of about 6 percent. Those who retire today or in the future will receive an average return of perhaps only a couple of percentage points. Higher-paid workers may well get back less than they contribute.4

Social Security, as I have said, was never originally designed to give workers the highest possible return on their invested payments. But if returns are low, or even negative, political support for Social Security could seriously deteriorate. Concerns about whether citizens will get their “money’s worth” from Social Security are among the principal reasons why some experts are now proposing privatization of all or, more often, part of the Social Security system. These experts include seven of the thirteen members of the government’s Social Security Advisory Council. Advocates of privatization plans also believe it is the best way to insure that retirement funds will not be tapped in the future for other purposes, such as Medicare. Some, including several members of the Social Security Advisory Council, would also use the reform plans as a way to try to raise the nation’s pool of savings.

By privatization, proponents usually mean that all, or more typically part, of a worker’s Social Security contributions would be owned and invested by him or her. The aim is to enable workers to earn a higher return than they will get from Social Security by putting their own funds in common stocks and other investments, as well as to assure them that they will receive their benefits without the threat that the federal government might one day use the money for something else. These plans are especially costly, however, because the current Social Security system must also be maintained while workers are still building up their own private savings accounts. And in the long run, a minimum set of benefits, usually known as the “first tier,” will have to be paid out by the government a) to protect those who make poor investments and b) to increase the retirement incomes of the large numbers of low-wage earners who cannot possibly save enough to provide even a reduced retirement income for themselves. The “second tier” of benefits would come from private investment of a portion of Social Security taxes or mandated savings of the retirees.

Consider the costs of one of the “two-tier” programs proposed by several members of the Social Security Advisory Council. It would require raising Social Security payroll taxes to 14 percent from 12.4 percent and, in addition, borrowing up to $1 trillion from the federal government to be paid back over the next thirty-five years. The privatized retirement plan in Chile, which is widely praised by most advocates of two-tier plans, including Peterson and Sam Beard, has only been able to absorb these high costs by borrowing heavily from its own government, which could afford it because it was running a large budget surplus at the time.

Advocates of privatization plans say they can increase the nation’s total savings in one of two ways: by reducing Social Security benefits substantially while maintaining the same level of taxes, or by imposing new taxes or mandatory savings plans. Sam Beard proposes a two-tier reform plan that would be financed by deferring receipt of Social Security benefits in exchange for what he calls Liberty Bonds. Those who can afford it will presumably voluntarily buy these bonds instead of collecting their Social Security benefits because they will want to pass this nest egg on to their heirs. If they don’t buy the bonds in sufficient numbers, however, Beard says he will make their purchase mandatory.

Peterson would both impose a mandatory savings plan and cut Social Security benefits significantly. His savings plan would require workers to save a hefty 4 percent to 6 percent of wages, part of which will be offset by a corporate contribution. The new savings accounts would be fully owned by workers who would manage them privately. At the outset, the savings plan would only be a supplement to Social Security. Peterson therefore says his is not a privatization plan. But as the new savings accounts grow in value, he anticipates that they could be substituted for Social Security contributions as long as a government-run minimum retirement program remains in place. This would indeed be privatization as it is currently defined.

His minimum program would be a reduced form of the existing one. In order to keep Social Security solvent without requiring additional funding, Peterson would raise the retirement age to seventy and sharply cut bene-fits for those retired households with incomes of $40,000 or more, which is, as he notes, about $5,000 more than the median family income. Peterson is a strong supporter of such means-testing. He is angry that so large a portion of Social Security benefits—about 40 percent—goes to retirees with incomes above the median. He would reduce all government benefits by 10 percent for every $10,000 of income that exceeds his $40,000 affluence test.

We should keep in mind, however, that median incomes are not middle-class incomes. Historically, middle class never meant the majority. To rise to the middle class was something to strive for. In fact, according to surveys, most Americans did not consider themselves middle class until the late 1950s. To live on $40,000 today is not easy. Peterson’s means test is a tough one.

Nor is it as certain as these reformers seem to believe that the nation’s pool of savings would be raised significantly if at all by these plans. Many economists believe that people have a more or less predetermined level of savings they seek to maintain. Mandatory savings plans would probably reduce voluntary savings. What is more, mandatory savings plans or Social Security tax increases could slow overall economic growth, holding back the rise in salaries and wages out of which additional savings must come. In my view, an incremental tax hike introduced at a very slow pace might well produce more savings for the economy because it would not deter growth and would gradually raise capital investment. This, in turn, might well increase growth in the long run. But such an assessment depends on many assumptions turning out to be accurate; and an increase in growth is not as predictable as some reformers claim.

Peterson and some likeminded reformers thus want to accomplish a great deal at the same time. They not only want to make Social Security solvent but also to increase the financial returns on workers’ contributions, raise the nation’s rate of savings, and insulate Social Security benefits from other government demands. Such ambitious programs, in my view, risk endangering the political prospects for doing anything at all. Most privatization programs are so costly that they are probably not politically feasible unless the government is willing to borrow still more money. What is more, if one of the main objectives of the reformers is to raise the return of Social Security for today’s workers, this can be accomplished at least as efficiently, and at lower cost, by having the government itself invest part of the Social Security trust fund in common stocks. This would be a departure from traditional American practice; but there was never before a large Social Security trust fund available for investment.

Robert Ball, who is also a member of the Advisory Council, proposes along with five other members of the Council that the trust fund gradually invest 40 percent of its holdings in an index fund of common stocks rather than investing it all in Treasury bonds with a smaller average return. An index fund is a statistically diversified portfolio of common stocks which is designed to rise and fall with the entire stock market. It would therefore not be dependent on any portfolio manager’s stock-picking abilities, and managerial fees would be very low. To invest Social Security funds in the stock market may at first sound risky. But if such a fund were built up gradually, a sharp but temporary drop in stock market values would, with high statistical probability, not be great enough to affect the ability to meet annual Social Security outlays.5

Some critics, including Peterson, point out that if Social Security funds are not invested in Treasury bonds, interest rates will rise to attract more investment in government bonds and the returns on stocks will fall. But even if we make an allowance for such a drop in returns, they would still provide a significant margin of difference that would raise returns on workers’ Social Security contributions substantially. In fact, there is good reason to believe that many workers would do far worse if their money was invested in the privatized accounts that have been proposed.6 According to Ball’s calculations, investing a large portion of trust fund assets in stocks would reduce the Social Security deficit by well more than a third. It would also have the great advantage of keeping the federal government’s hands off the money that goes into stocks.

3.

Nevertheless, privatizing Social Security, which was hardly discussed even two years ago, is rapidly gaining adherents. Distrust of government is high and growing while, at the same time, some of the schemes put forward seem to promise higher benefits. A report by a World Bank economist in late 1994 that favored such plans may have provided impetus for the idea.7 This may be one of those historical moments when the public is yearning for change—but if so, it would be a deeply unfortunate one. Even partial privatization threatens to increase social divisions in the US at a time when we are already divided enough by an increasingly unequal distribution of income, by falling wages for the less well-educated, as well as by rising levels of poverty, poor public schools, and inadequate health insurance for the working poor. As privatization programs mature, and more workers have private portfolios of invest-ments, it would only be natural that workers increasingly come to resent the 3 percent or 4 percent of their income that is diverted from their own retirement programs to support lower-paid workers.

As a result, these plans will tend to separate the better-off or even middle-income workers from the rest of the nation; and they could well undermine middle-class support for a Social Security system that will increasingly appear to be another welfare program. Subjecting Social Security to a severe means test, as Peterson proposes, might also reduce middle-class support for Social Security as the better-paid workers receive fewer benefits from the program. It may be intuitively obvious that well-to-do people, like Peterson himself, should receive diminished Social Security benefits, or none at all; and a means test for such retirees might make sense. But there are too few rich people to make the elimination of their benefits a significant help in reducing the coming Social Security shortfall. Because of the progressive distribution of benefits, high-income retirees will already receive poor or even negative returns on their Social Security contributions. To make a financial difference, Peterson’s plan must reach down almost to the median family income to start means testing, thus potentially weakening political support for the program among a vast number of Americans. The unspoken appeal of privatization may well be that it allows the middle class to reduce its commitment to help those who are less fortunate.

To Peterson’s credit, he concedes that such a problem may arise. His book is admirable for his willingness to take on critics. But he doubts Americans would become so callous. This, I think, disregards the support of most Americans for the recent welfare reform legislation that inflicts hardship on hundreds of thousands of children. If day care or early education programs were available to 90 percent of all American children, for example (as is Social Security to our poor and middle-class parents and grandparents alike), they would be far less likely to lose political support. Wilbur Cohen, President Johnson’s Secretary of Health, Education and Welfare, presciently warned nearly forty years ago that a program for the poor is usually a poor program.8

Defenders of the current publicly financed Social Security system should recognize, however, that the time may have come when the elderly, too, will have to pay some of the price for a workable and stable society now that resources simply are not increasing as they once did, and America’s children, one out of five of whom grow up in poverty, are so seriously neglected. For these reasons, cutting Social Security benefits moderately is necessary. For example, it would make sense to raise gradually the retirement age to seventy, while retaining some benefits for early retirement, and changing the earnings formula slightly to reduce average benefits. The majority of Social Security recipients already retire early. The right way to improve the value people get from Social Security and maintain the support of the middle class is not privatization but investing trust fund assets in common stocks. The sooner these changes are made, the faster will be the buildup in assets and the lower the future costs to maintain the system.9

As for Medicare and associated health care programs, it would be a mistake, in my view, to hold Social Security hostage to them. The rising costs of health care require imme-diate attention but they should for the most part be dealt with on their own. Among the remedies being proposed are raising the Medicare eligibility age, hiking taxes, and more far-reaching plans to encourage competition among medical care suppliers and to place a greater financial burden on beneficiaries, who will thus be encouraged to spend their money more cautiously. It is not at all clear as yet whether such changes will accomplish the goal, or do so equitably. But at the least a determined political effort is needed to dramatize the need for a new, more inclusive system, separate from Social Security, that keeps costs from rising at current rates. One exception might be for long-term care for the elderly. Its costs are rising astronomically, and these might eventually be funded, at least in part, by the Social Security program.

Certainly the nation would benefit in the long run if it could raise its rate of savings. But even if it proves more practical politically to try to increase savings by using the Social Security system, privatization is surely not required. A modest hike in the Social Security tax so as to raise revenues slightly above what is needed to make the system solvent could accomplish this. At least it could do so if the federal government is kept from using for other, non-Social Security purposes the additional buildup in the trust fund that would result in such an increase.10

Reforming Social Security cannot accomplish everything that is needed to make the American economy work better, but some of the outspoken reformers seem to want to do just that. As a result the necessary, practical Social Security reform that is certainly needed could be sidetracked. Amid the current loosely argued and often heated debate, we should not lose sight of the central facts: that Social Security has worked extraordinarily well for sixty years; that it can be maintained with significant though not radical reforms; and that it is one of the few public programs that bring all Americans together.

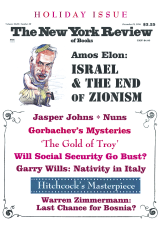

This Issue

December 19, 1996

-

1

Adjusted for inflation, the $92,000 in benefits is worth only about $15,000 today. The $1 million annuity is worth about $150,000.

↩ -

2

Needless to say, one has to be skeptical about any seventy-five year forecast, or a twenty-five year forecast for that matter. But the Social Security Administration (SSA) forecast is based on middle-of-the-road estimates of future wage growth, employment, and population increases; it is neither especially optimistic nor especially pessimistic. It assumes that the slow productivity growth of the last two decades will continue and that inflation will be on average higher than it currently is. But it assumes as well that wages will rise faster than they have.

↩ -

3

Although many observers, and even experts, take it for granted that the Consumer Price Index significantly overstates the actual rise in prices, government experts and some private economists who have examined the issue have found much less reason to support this point of view. The Boskin Commission of five private economists has issued a preliminary report claiming the index significantly overstates price rises; but it is based on no new empirical evidence. For now, it should be noted that there is still much debate over this issue.

↩ -

4

Yung-Ping Chen and Stephen C. Goss, “Are Returns on Payroll Taxes Fair?” in Social Security in the Twenty-First Century, p. 83.

↩ -

5

To make this plan work requires that Social Security be partially funded in advance. Ball’s plan would accomplish this by reducing benefits slightly, as discussed earlier, without reducing taxes.

↩ -

6

Some observers complain that stock investors, whose returns might fall, would be paying a share of Social Security’s costs. I see this as a benefit, not a drawback. The additional shared cost would be small, anyway. Moreover, if Social Security, which is some ten times larger than the largest pension fund, is willing to accept the higher risks of investing in stocks, risks which a very long-term fund like Social Security can absorb, it may indeed raise the nation’s rate of economic growth by promoting more risky, longer-term investment. This is a subject that, to my knowledge, hasn’t been carefully addressed by economic experts as yet. But an economy that can take more risks is likely, in the long run, to grow faster.

↩ -

7

Averting the Old-Age Crisis (World Bank, 1994).

↩ -

8

Eric R. Kingson and James H. Shulz, “Should Social Security Be Means-Tested?” in Social Security in the Twenty-First Century, p. 50.

↩ -

9

To put this in perspective, if we waited until 2029 to impose a tax increase to make Social Security solvent, it would have to be about double the 2.2 percent that would be required if the tax were imposed today.

↩ -

10

One reason Social Security is such an appealing way to raise the nation’s pool of savings is that Social Security taxes are not deductible. Any increase in those taxes is a net addition to savings, provided they don’t slow economic growth, because the federal government does not lose tax revenues. For a proposal along these lines, see the interesting piece by the economist Barry Bosworth, “What Economic Role for the Trust Funds?” in Social Security in the Twenty-First Century, p. 156.

↩