“Another hour passed,” we read in Fitzgerald’s Last Tycoon. “Dreams hung in fragments at the far end of the room, suffered analysis, passed—to be dreamed in crowds, or else discarded.” Hollywood, long thought of as the dream factory, has probably more often been the cemetery of dreams, the place where possibilities flicker for a moment and die before they reach the world. By the 1970s the creation of discardable (and discarded) dreams appears to have become a major activity of the movie industry, the way it kept itself going. You made a film now and then, but mainly you made deals, put packages together, ran with them for a bit, and then at some lunch or meeting or other you dropped your package and picked up another one. “It had been a very creative deal,” Joan Didion wrote in The White Album of a movie that hadn’t happened, “and they had run with it as far as they could run and they had had some fun and now the fun was over, as it also would have been had they made the picture.”

Packages often started as concepts, drastic plot summaries yearning for a deal, a situation memorably parodied in Robert Altman’s film The Player, where all movie ideas are permutations of already permutated ideas, and the pitch, the talk of what the movie will be like, is everything. “It’s Out of Africa meets Pretty Woman,” one pair of writers says about one of their projects. “Like Ghost meets The Manchurian Candidate,” another writer says about his “psychic political thriller comedy—with a heart.” In Monster John Gregory Dunne defines “high concept” as “a picture that could be described in a single line, such as Flashdance (blue-collar woman steelworker in the Rust Belt becomes a ballerina) or Top Gun (cowboy Navy jet jockeys train and love at Mach 2), pushed along by a hit-music track.”

Dunne thinks the Hollywood writers’ strike of 1988 changed much of this, especially the pictureless running and the expensive fun. The studios wrote off “hundreds of projects in development, and the necessity of paying for them once the strike was settled.”

Once profligate in developing scripts, only a fraction of which ever went into production (it was not unusual for writers to make several hundred thousand dollars a year for years on end without ever seeing a picture go before the cameras), the studios…were in a feisty, fee-cutting mood.

The Disney studio, known locally, Dunne tells us, as Mouschwitz or Duckau, was particularly tough, and readers of The New York Review will recall the story Dunne relates in a previously published excerpt,* and now in this book, of the Disney executive and the monster. A writer is arguing about changes to a script. The executive, losing patience, says he has to take the monster out its cage. He pretends to produce “a small predatory animal” from under the table, waves the (invisible) creature in the air, and mimes its restoration to its cage. The executive asks the writer if he knows what the monster is. The writer shakes his head. The executive says, “It’s our money.”

Dunne doesn’t gloss this little parable except to say that the executive himself finally met the monster and got fired, but it is worth pausing over. No one can have thought the money was anyone else’s, so the monster is not the money or the possession of it but the naming of it, the pulling of rank and clout when you can’t win an argument another way. In fact, the situation in the story is one degree more oblique than that, since the executive doesn’t release the monster, only parades the possibility of its release.

This is bad enough, though, and it was in this unpromising climate that Dunne and his wife, Joan Didion, began their work, in 1988, on the Disney movie which was to become, in 1996, Up Close & Personal, directed by Jon Avnet and starring Robert Redford and Michelle Pfeiffer. Monster, Dunne says, is “a story about the making of that movie, about the reasons it took eight years to get it made, about Hollywood, about the writer’s life, and finally about mortality and its discontents.” That’s a fair description of the topics of the book, but it doesn’t represent the proportions of its interest or its tone.

About half the book is about not making the movie, about lulls and rewrites and haggling. The writer’s life is logged but not really evoked. There are deaths of friends and family within the time frame—those of the director Tony Richardson, the writer Andrew Kopkind, the producer Don Simpson, Joan Didion’s father, Frank Didion, the producer John Foreman, who first set up the project of Up Close & Personal—and Dunne himself has heart surgery with some scary consequent complications, while Didion suffers a detached retina. Death, Dunne writes, has become “the most implacable and cruelly effective monster,” making Disney look like small-time. We accept the truth of this but don’t feel the force of it, partly because the image is too predictable, and partly because Dunne, as a writer, is too cheerful, too irremediably breezy. This is what makes him so readable, but it doesn’t give him a voice for brooding. “I felt like Hans Castorp in The Magic Mountain,” he says of his spell in Columbia Presbyterian Hospital, but the context suggests an elegant screwball comedy, with death in the far background, all sadness displaced into the aura of nostalgia and then pretty much cancelled by Dunne’s amazing good humor: Adam’s Rib meets The Seventh Seal.

Advertisement

Every afternoon between three and four, high tea was served, while a cocktail pianist in black tie played such the dansant favorites as “Send in the Clowns” and “Isn’t it Romantic?”…I would be eating cake and drinking tea, a portable IV taped to my arm, dripping antibiotics into a vein, when a gurney would speed across my sight line, either conveying a patient to or bringing him or her from a medical procedure, while in the background the pianist played “Bewitched” or “Just One of Those Things.”

Mortality has its charms while it lasts. We can see why Dunne might be daunted, indeed must have been, but we can’t see where. This is a considerable attraction, especially if you weren’t particularly looking forward to the stuff about the discontents. Even the endless contractual hassles recorded here, which must have driven Dunne and Didion mad, appear as a tough but vivifying game, like boxing without gloves. “In twenty-seven years of writing movies,” Dunne says, “I…have never been through a contract negotiation that could not reduce me to a splenetic rage,” but the rage itself seems energizing, and Dunne speaks of ripe insults which “trip lightly off my tongue.” “This was a battle with the monster we were prepared to enjoy,” Dunne writes at one point. The monster here is Columbia Pictures, but death can expect the same resistance.

Mortality is undeniable, but this is a book about small wins against great odds. You win chiefly by being smart and keeping busy. “It takes approximately eight weeks to recover fully from open-heart surgery, and by the middle of May 1991, I was back working on my novel.” No malingering there; the monster will have to wait until there’s a space in the calendar. This book has two revealing, understated postscripts, one called an envoi, the other a coda. The envoi tells us what else Dunne and Didion worked on and completed during the eight years they were involved with Up Close & Personal: two novels (one each), six works of nonfiction, seven screenplays, many substantial, high-profile magazine articles. Dunne then adds: “We also had a good time.” The coda tells us that Up Close & Personal, which cost $60 million and had made $100 million within six months of its release (in March 1996), will in the end, “when the revenue from film rentals, video, cable, mainstream television, and all ancillary markets is com-puted…have made Disney a small profit.”

I’m not sure whose criterion of size is being used here, but the implied point is clear: it was a lot of work for not much, no one is grateful, but it didn’t get in the way of other work, or of enjoying life. We return to the discreet double meaning of Dunne’s sub-title. You can live off the monster if you are careful and industrious, and living off-screen has its attractions. “It was Michelle Pfeiffer, after all,” Dunne says, deciding to leave certain character developments to the actors and the director, “who was going to be twenty-five feet tall up there on the big screen in a darkened theater, not us.”

Michelle Pfeiffer, an intelligent actress with a string of wonderful performances to her credit, might also have preferred, in retrospect at least, to see someone else on the big screen in Up Close & Personal. The movie is very tame, and the fault is partly hers, because she can do ineptness and poise as a TV journalist but nothing in between, and the story is supposed to be about what’s in between, the development of the raw girl from Reno into a top national network newswoman. Her mentor is Robert Redford, a once-famous reporter rusticating in Miami, with a great future behind him. They fall in love, he teaches her everything he knows, and he dies on a dangerous assignment in Panama, back on the front line, but also killed before he can become an inconvenience to Pfeiffer’s rising star or the now-fading plot.

Advertisement

The movie has one fine, delicate moment. Pfeiffer finds herself caught up in a prison riot in Philadelphia, the only reporter inside. Redford, in a van outside, cues her with questions via the radio/computer equipment, then realizes she no longer needs the cues, that she is already asking the very questions he is feeding her. He sits back in his chair, smiles very slightly. Redford is good in this film, underplaying everything, at home everywhere, as if he is taking a holiday from All the President’s Men but is still in character. But the direction, apart from this moment, is heavy and slow. Maybe a sleazy agent, played by Joe Mantegna, can be allowed to get away with saying to Pfeiffer, “I was wondering when you would walk into my life,” but then if anyone is going to comment critically, as Kate Nelligan is made to, they need to say more than “Please,” and they need not be given what feels like about five minutes to do it.

Dunne and Didion have to bear some of the responsibility here, since they are the ones who wrote the lines, along with “I figured, if you’re hungry enough to fake it, you’re hungry enough to do it,” “Why didn’t we do this before?” and “When we’re not together…everything shuts down.” Monster is dispiriting reading in this respect. Having seen the movie, I was hoping to learn that the writers abandoned it to its fate, keeping their names on it only for reasons of credit and credibility. But no. They wrote and rewrote, and even helped with the cutting. A difficult relation with the apparently impossible Jon Avnet turned into a warm working friendship, even if mainly conducted by phone and fax.

Dunne is calm and amiable about the reviews the film got—a decorous response if you’ve taken some money off the monster, and the monster is happy, and you’re still alive. The negative reviews, he says, called the picture “schmaltzy, shallow, predictable, without conflict.” Dunne thinks this is true. The positive reviews called it “schmaltzy, shallow, and predictable, then added that it was a glamorous, old-fashioned, star-driven Hollywood love story.” “True again,” Dunne says. Scott Rudin, for much of the crucial preparation time the movie’s producer, kept reminding everyone what the film was really about: “It’s about two movie stars.” You can’t argue with such a likeable refusal to argue; you’re just left wishing someone could have found a little more steam somewhere, some glittering schmaltz, or dazzling shallows. After all, Pauline Kael called Citizen Kane a shallow masterpiece. Up Close & Personal has stars in it, but it isn’t star-driven. It isn’t driven at all.

Why wasn’t the movie completed earlier? Because Disney wouldn’t make it and wouldn’t kill it; because Dunne and Didion quit and were lured back, then quit again and came back again; because no producer before Scott Rudin looked as if he was going to make anything happen. All of this dizzying non-activity is related in detail and with relish, and is far more fun than the account of the making of the film which comes along later in the book. Dunne has a great ear for Hollywood idioms, and a style which expertly recreates and focuses them. “We feel this project has a lot of potential,” a Warner Brothers note begins; the translation, Dunne says immediately, “is file and forget.” “The best first draft I ever read” merely means this is “the first of many drafts.” Dunne and Didion are told by the producer Jerry Bruckheimer that they have made “a major contribution to the project, it was headed in the right direction, and…we were going to get paid in full, even for the changes and drafts and polishes we had not yet written.” The project was a movie called Dharma Blue, an action picture about a UFO cover-up.

“We just got fired,” I said to Joan when we hung up.

“No, we didn’t get fired, we’re getting full payment,” Joan said.

“Babe, you sound like Robert McNamara wondering if Lyndon Johnson had really fired him when he shipped him to the World Bank.”

Do you know what CEs are? Creative executives.

These are young men and women in their twenties and early thirties who function as readers, gate-keepers, and note-takers, a callow Swiss Guard working cruel hours six and seven days a week for an annual salary of forty to forty-five thousand dollars, and the remote possibility of one day sitting at high table with the decision makers…. Since studio vice presidents or Presidents in Charge of Production consider it beneath their dignity to jot down or even remember the thoughts they advance at script meetings, notes are transcribed by CEs, who often add their own spin to the mix. Jargon is a CE’s currency. A screenplay must have a “creative arc,” ending in “resolution,” or a “controlling idea” leading to “the inevitable climax”; major characters almost always lack “motivation,” and sometimes “basic motivation.”

“Or even remember” is a wonderful touch, and that lack of “basic motivation” makes you think your life might be a movie script that needs work. The most interesting of these Hollywood idioms involves the word “open,” whose meaning might seem obvious enough. Not so. “Open” means doing well at the box office “on the first weekend, more specifically on the first Friday night, of its release.”

Here we have yet another monster: it was our money, but it’s gone.

A picture that “opens”…gets the advertising and the promotion and the interviews and the television spots…. A bad Friday night, that is, a big picture that does not open, is the spectre the studios fear, the monster that rampages through jobs and careers, perks and bonuses.

And if Dunne is discreet and funny about his own health and his work, too relaxed to conjure up the truly monstrous darkness, he can certainly catch the manic energies of Hollywood players at their furious best. Here, in brilliant indirect speech and then in dialogue, is Dunne’s impression of Scott Rudin in action:

Deliver the moment, he would say. We need a stronger credit sequence, use the bookend frame, we have a POV [point of view] deficit, we want another beat here, deliver the moment, stretch it out, this is clunky, Houston is too one-note, up it, cut all the Washington chat in the S&L scene, but save her line, “Get the fuck out of my shot,” it’s who she is, lose the Taco Bell sequence, its OTN (for “on the nose”) or OTT (for “over the top”), split the first newsroom sequence, do it over two days,d eliver the moment, goose the scene, deliver the moment, put the sex back in the first act, get the sex going in the newsroom, deliver the moment, we need more romance, deliver the moment, deliver the moment, deliver the moment, there’s room for romance, it’s a love story.

I don’t do love, I finally told Rudin in some exasperation. That’s hilarious, Rudin said.

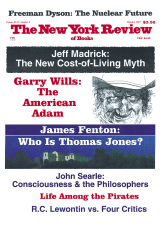

This Issue

March 6, 1997

-

*

The New York Review, October 17, 1996, pp. 25-29.

↩