1.

No recent book has blown a bigger hole in the proposition that the US must follow a policy of “positive engagement” with China than The Coming Conflict with China. It is a mark of the wound they inflicted on Peking that the authors, ex-reporters in Peking, Richard Bernstein for Time magazine and Ross Munro for the Toronto Globe and Mail, have been identified by Xinhua, the official New China News Agency, as

extremely domineering and conceited…viewing things with prejudice and racial discrimination… and defaming China’s socialist system because it did not collapse as they wished after the collapse in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe.

The essential question raised by their book is how to deal with China. Should American criticisms of Chinese behavior, whether toward Taiwan or Hong Kong, American exports, or China’s own dissidents, be offered behind a diplomatic screen, so to speak, where they are allegedly most effective in a culture that values “face”? Or should Peking be confronted like any other country when it challenges basic American interests? Bernstein and Munro want the US to be much more willing to openly oppose Chinese policies than the Clinton administration has been. They speak in large geopolitical terms of China’s prospects for gaining a dominant, and intimidating, power in Asia; and they even foresee that in some circumstances it may be necessary to have a “face-off” with China, for example if Peking were to attempt to take over Taiwan by force.

If the kinds of threats from Peking the authors anticipate become realities, however, I believe it will be too late to deter China. And going to war is unthinkable. But President Clinton has stated that the United States will “stand with those who stand for freedom in Asia,” and he has included Hong Kong on his list. I will argue here that Washington should immediately establish Hong Kong as a test case, making plain to Peking that unless it adheres to its treaty obligations there, it will encounter American obstacles to its full international acceptance.

The authors believe that China’s intentions are plain: it is an “unsatisfied and ambitious power whose goal is to dominate Asia.” Such a goal, they write, is “directly contrary to American interests.” The most important of these interests is that the US maintain its position as “the preeminent power in Asia….” This is the kind of statement that gives Xinhua the opportunity for a counterpunch at Bernstein and Munro. “They feel,” the Chinese agency says, “extremely happy about their country’s hegemonic acts throughout the world.” Their attack on China’s motives “represents a typically indecent way of thinking—gauge a noble heart with one’s own mean measure.” By the end of its attack Xinhua has slid from The Coming Conflict with China to America itself. “The United States is acting like a villain who sues his victim before he himself is prosecuted. Its ultimate goal is to stifle China.”

The racist innuendo aside, Xinhua is correct: Bernstein and Munro want the present Chinese system to collapse. Indeed they regard its collapse as inevitable if China becomes more democratic—although they doubt it will. But it is not “China’s socialist system” they attack. China, they claim, “seems moving toward some of the characteristics that were important in early-twentieth-century fascism.” These include a cult of the state, for which the individual must sacrifice himself; the emergence of a powerful army with both political and economic authority; a disciplined ruling party, whose leaders and their children control state corporations, weapons’ manufacturing, and banking; and “a powerful sense of wounded nationalism.”

There is little in traditional or modern Chinese “political culture,” they say, that would welcome democracy. And democratic reforms in China—opposition parties, free elections, a free press—would force its present leaders to yield power, which they do not intend to do. Indeed, China’s leaders “are probably sincere in their equation of democratic reform with social chaos.” If what Bernstein and Munro would like to see happen in China comes about—namely democracy—the current system, in their view, could not survive. Still, they write that “the ultimate American objective on China is to induce China to behave responsibly and to become more democratic.” Democracies, they say, are less likely to start wars.

In the last paragraph of their last chapter Bernstein and Munro suddenly veer away from their apocalyptic vision and from the very title of their book, saying they have met many young Chinese “for whom antagonistic nationalism has no appeal.” American diplomats should remain in contact with such “cosmopolitan and liberal segments of the vast Chinese nation,” who can steer China onto a less dangerous path. If there are so many and it is so easy to meet them, perhaps the authors are too pessimistic. But they do not explore this possibility in the body of their book.

Advertisement

This is a mistake which threatens their thesis. Except for their anomalous last paragraph, the authors give the impression of a Maoist China of one mind, certain of its intention. Recent visitors give a different impression, of a Peking and indeed of a country in which factions compete to make internal and international policy. Lucian Pye, of MIT, puts it well:

The leitmotiv of Mao’s China was orthodoxy, conformity and isolation, a whole people walking in lock-step, seemingly with only one voice, repeating one mindless slogan after another…. In amazing contrast, Deng’s China was a congeries of elements, not an integrated system at all…. Above all, economics and politics seemed to be adhering to different rules, so that there was openness here, controls there…. A “fragmented authoritarian” system in Kenneth Lieberthal’s well-chosen words.1

Apart from their last-minute optimism, the authors see China as an enemy of the United States. They quote a senior Chinese analyst: “In the coming fifteen years there won’t be fundamental conflicts between the United States and China but after that fundamental conflict will be inevitable.” They quote, too, a famous remark in 1996 of General Mi Zhenyu, Vice-Commandant of the Academy of Military Sciences: “[As for the United States] for a relatively long time it will be absolutely necessary that we quietly nurse our sense of vengeance…. We must conceal our abilities and bide our time.” For Bernstein and Munro the primary American objective is therefore quite clear: “to prevent China from becoming the hostile hegemon …in Asia.” (The word “hegemon” here especially nettles Peking, which formerly used it against both the Soviet Union and the United States, and now reserves it for the US alone.)

The authors do not predict that a military collision between China and the US is bound to come—unless Peking continues to press its claims to dominate the sea lanes in the East China Sea or, more dangerously, if it attempts to retake Taiwan by force. If Washington allows Taiwan to fall, they ask, “what will be the implications for the survival of credible American power elsewhere in Asia and the Pacific?” American power, they make it clear, will be undermined and the East Asian nations will increasingly submit to Chinese domination. This foreboding is not eased by Peking. In its criticism of The Coming Conflict, Xinhua refers to Foreign Minister Qian Qichen’s recent statement that there was no possibility of a US-China war—“unless the United States violates China’s territorial integrity and sovereignty….” China considers Taiwan an integral part of its territory.

But military collision apart, Mr. Bernstein and Mr. Munro argue that political conflict “seems to us to be the most likely condition of Chinese-American relations for the foresee-able future.” They criticize those prominent American politicians, academics, and businessmen who claim that to openly criticize or oppose Chinese behavior is to provoke China for no visible return. Those who hold this view usually maintain that China has a weak army, is not expansionist, and does not menace the interests of the United States or China’s neighbors, while, at the same time, its growing economy presents important opportunities for trade with the US. According to their argument, China, with its traditional regard for “face,” is easily insulted, but really needs the US as a guarantor of stability in East Asia. “Over the long run, China and the United States are fated to be global partners, even if…there are periods of tension.”

The authors call the exponents of this view “The New China Lobby,” which they say ignores that China “is in so many ways an adversary, a dictatorship, an emerging superpower whose interests are at odds with those of the United States.”2 Among the members of this lobby the authors cite former Secretaries of State Henry Kissinger, Alexander Haig, and Lawrence Eagleburger, as well as former National Security Adviser Brent Scowcroft. Some of these men, the authors write, have represented American companies doing business in China; but they do not claim that their views have been determined by their financial interests. Bernstein and Munro refer also to “a contingent of a half a dozen or so senior scholars of China whose careers have flourished…in part because they have been granted access at a high level in China.” They fear being cut off from that access if they offend Peking and so on sensitive subjects they find it best “either to flatter or to remain silent.” The authors, who are explicit in referring to ex-officials who have business connections in China, are reticent about the identity of these “senior scholars of China.”

While unmistakably polemical, The Coming Conflict with China is also persuasive. Its chapter on the Chinese army, for example, shows that while Peking’s declared military spending is $8.7 billion, a pittance compared to the $265 billion spent by the US, the Government Accounting Office in Washington concludes that it is actually three times greater. And the authors “believe that the multiple is much higher—indeed that it is between ten and twenty times the official figure.” Published military budgets, they point out, exclude nuclear weapons development, the purchase in 1995 of $2.8 billion worth of Soviet fighter jets, arms sales abroad, and the PLA’s earnings from its roughly twenty thousand companies. If China’s military budget is ten times higher than it acknowledges, this would put China’s defense spending at $87 billion, or nearly one third of the American figure. The authors note that “whether or not China ‘catches up’ to the West is not the important question.” China already has the largest military force in Asia and “the only one which has deployed nuclear weapons.”3

Advertisement

But despite such ominous evidence, Mr. Bernstein and Mr. Munro contend, Washington has “sent a clear message that in any test of wills” with China, “the United States will back down in the face of the inflexible determination not to yield.” Except when it sent two aircraft carriers to the Taiwan Strait in March 1996 after Peking began military maneuvers during the presidential elections on the island, the US nowadays prefers to say little or nothing when China sells weapons of mass destruction to what Washington calls “rogue nations” such as Libya, violates the human rights of those inside its borders, isolates Japan as an Asian power by constantly raising the question of war guilt, and extends its power throughout Asia, as “a powerful economy creating a credible military force.”

The authors urge Washington to remain militarily strong in Asia. The US should make clear that it is willing to defend Taiwan and to assist Japan in becoming a counterweight against the growth of Chinese power in the western Pacific. It should use economic pressure by annually reviewing China’s Most Favored Nation trade status and delaying its entry into the World Trade Organization. Because Peking “is using billions of American dollars to buy state of the art weapons systems from Russia and Western Europe,” its trade surplus with the US of nearly $40 billion should be reduced.

Nonetheless, Bernstein and Munro favor Clinton’s policy of separating human rights from trade relations. They believe that neither imprisoned dissidents nor Tibetans should be allowed to threaten America’s long-term economic or military interests.4 But they insist that Washington should continue to stand up for human rights by using the UN and other international forums to scrutinize and publicize Chinese human rights violations. The US should provide funds for Radio Free Asia and maintain “cool and correct” relations with the men President Clinton once called “tyrants.” It should not turn meetings between high-level leaders into “a festival of friendship.”

The authors occasionally mention Hong Kong as important, and describe it as one of the two places—Tibet is the other—“where human rights concerns either do or might bedevil relations between Washington and Beijing.” Even before the takeover of Hong Kong, China is “ensuring that its control would be unquestioned.” Peking, they predict, will probably curtail human rights there, arresting dissidents, closing down newspapers, and so on. This would present the United States with “the usual dilemma: wanting to take steps to stop the violations but having little real power to do so.” The authors correctly point out that Peking is bound by its 1984 treaty with Britain to allow Hong Kong considerable autonomy and a separate way of life; they might have pointed out as well that this denies the Chinese the opportunity to dismiss remonstrances about Hong Kong as an “intrusion into our internal affairs,” their usual riposte to any criticism from abroad. The US, therefore, because of its economic and other interests in Hong Kong, should “insist that China respect its commitments and protest loudly and vigorously if it doesn’t.”

2.

This analysis is perceptive as far as it goes. But in my view the authors do not sufficiently appreciate what is at stake in Hong Kong. American policy toward the takeover, which has been contradictory so far, may deeply affect US relations with China and Asia for years to come.

What will China do? Professor Michael Yahuda of the London School of Economics, in his subtle book Hong Kong: China’s Challenge,5 thinks that Peking stands to profit by retaining Hong Kong’s present way of life.

If China’s communist leaders were able to honor the pledge of allowing Hong Kong to maintain its rule of law and basic freedoms…China would continue to benefit from the enormous contribution the territory makes to its modernisation…. Such a display of tolerance for an autonomous Hong Kong would consolidate its new relations with Chinese communities outside China, strengthen Beijing’s stance regarding Taiwan, reduce anxieties in Southeast Asia, ease China’s relations with the USA and Japan…and improve China’s international standing generally.

Professor Yahuda is much more hopeful than I am. Peking, in my judgment, has seen Hong Kong as a major source of sedition since June 1989, when a million of its people turned out in demonstrations against the Tiananmen killings. It fears the growth of a democratic movement, visible especially in the results of the two elections for the Legislative Councils that were held since 1991, when the leaders of the 1989 demonstrations were able to form the Council’s largest bloc.

Whether that movement will be suppressed is an urgent matter for the city’s 6.1 million ethnic Chinese who for the most part are not enthusiastic about the Mao-Deng-Jiang Communist Party state, which will become their sovereign on July 1. In their 1984 agreement with the British the Chinese promised a “high degree of autonomy” other than in defense and foreign affairs and it gave similar assurances in the 1990 Basic Law, China’s mini-constitution for Hong Kong. But so far, China has given many signs of flouting its legal obligations to Hong Kong. This challenges the concepts of “positive engagement,” let alone partnership, that are frequently voiced in Washington and in the region. Such a challenge, if not countered immediately, will reveal as mere cant President Clinton’s guarantee of November 26, 1996, that “the United States will continue to stand with those who stand for freedom in Asia and beyond.” So also would the US be betraying the language of the United States-Hong Kong Policy Act of 1992, signed by President Bush, which states:

The human rights of the people of Hong Kong are of great importance to the United States and are directly relevant to United States interests in Hong Kong. A fully successful transition in the exercise of sovereignty over Hong Kong must safeguard human rights in and of themselves.

Those solemn-sounding undertakings may not be much publicized in the US today, but they are well-known in Hong Kong and in other parts of Asia. If the US government ignores them, it would be seen as weak and hypocritical.

Already Peking has condemned American concern about liberty in Hong Kong as “interference” in its sovereignty and as showing “hegemonic” insensitivity. And now, well before the takeover, it is undermining fundamental aspects of Hong Kong’s “autonomy” that are entirely unrelated to either foreign affairs or defense.

Peking has declared that at one second past midnight on July 1, Tung Chee-hwa, its Peking-appointed chief executive, will assume control. The wholly elected Legislative Council that now runs Hong Kong will be replaced by one appointed by Peking. A Chinese garrison, whose soldiers may not be subject to local laws if they commit civil crimes, will take over from the British one. The current laws guaranteeing rights will simply disappear, notably citizens’ rights to demonstrate without asking for police permission.

Also just after midnight on July 1, the National People’s Congress of China will become the de facto court of final appeal on what Peking, in its 1990 Basic Law, terms “acts of state.” No one has defined what these are, but it seems a safe bet that they will include active opposition. The Chinese have appointed their own Provisional Legislative Council which is already meeting to consider laws banning subversion, secession, and treason; some of these will apply to criticism published in the press. Elsie Leung, whom Mr. Tung appointed as secretary of justice for the post-July government, has said the new laws could make it illegal to shout, “Down with Premier Li Peng.”

In such circumstances how can President Clinton’s policy of “constructive engagement” be used to protect Hong Kong? It will be difficult, now that the officials and academics who advise the President have apparently convinced him that confronting China does not pay off, that China’s sensitivity to “face” means that it is unwise to do more in public than “regret” the imprisonment of dissidents or persecution in Tibet. When Clinton met President Jiang Zemin after the APEC meeting in the Philippines, none of those traveling with him I talked to would acknowledge that he even mentioned the plight of political prisoners. Indeed, since “constructive engagement” began in 1995 all Chinese dissent has been silenced or is heard only from abroad.

Washington may still wish for a “partnership” with such a regime. Warren Christopher was prepared to offer this explicitly in Shanghai in November until the word was dropped from his speech at the last minute. It is true that Peking rejects all foreign criticism as “violations of Chinese sovereignty which hurt the feelings of the Chinese people,” although it does not shrink from criticizing the US as power-hungry or from calling Hong Kong’s governor, Chris Patten, a “whore” and a man to be condemned “for 10,000 years.” Nor did it show any reluctance to fire missiles near Taiwan just before the elections there, or to conduct invasion exercises on the China coast opposite Taiwan.

The immediate question is what the Clinton administration will do to hold China to its freely given word on Hong Kong; and here the US has from time to time been making assurances similar to those that Bernstein and Munro call for. To take the most forthright example, much cited in Asia, Clinton spoke as follows at Bangkok’s Chulalongkorn University on November 26, just after he had avoided using such language when he met with Jiang Zemin in the Philippines.

The United States is proud to have supported democracy’s march across Asia. We do not seek to impose our vision of the world or any particular form of government on others. But we do believe that freedom and justice are the birthright of humankind. The citizens of Thailand, Japan, Hong Kong, South Korea, the Philippines, Taiwan show us that accountable government and the rule of law can thrive in an Asian climate…. The brave reformers in Burma led by Aung San Suu Kyi remind us that these desires know no boundaries…. The United States will continue to stand with those who stand for freedom in Asia and beyond. Doing so reflects not only our ideals, it advances our interests. [italics added]

The same kind of expression of moral obligation tied to US interests can be found in the already mentioned US-Hong Kong Policy Act of 1992. This stipulates that beginning in 1993 the secretary of state, on the last day of March every year until the year 2000, shall report to the Congress on “the development of democratic institutions in Hong Kong,” and that “whenever the President determines that Hong Kong is not sufficiently autonomous to justify treatment under a particular law of the United States,” the President may suspend that law.

In fact, the US concern for what happens in Hong Kong has recently seemed, at least, to become more explicit in Hong Kong itself. Speaking to the Chinese Manufacturers’ Association of Hong Kong in March, the US Consul-General, Richard Boucher, referred to “the open free society which underpins its [Hong Kong’s] success,” and said of the commitments China made in the Joint Declaration of 1984 and the Basic Law of 1990, “these are good ones and we expect them to be fulfilled…. As July approaches, Americans will be watching Hong Kong’s return with intense interest.” In almost every meeting with Chinese officials, Mr. Boucher noted, “we…regularly stress the importance of Hong Kong remaining free and open….” [italics added]

If Peking and its agents in Hong Kong enforce their will in Hong Kong in the interests of avoiding “chaos” and ensuring “stability,” and if Mr. Tung gets his way and “obligations,” “the family,” and other “Chinese values” replace the liberties for which Hong Kong’s people and Legislative Council have repeatedly voted since Tiananmen, Mr. Clinton’s promise to “stand with those who stand for freedom in Asia and beyond,” which included Hong Kong, will be put to the test.

Secretary of State Albright suggested on Meet the Press in early March that the US is concerned but should not “overreact” to China’s legal and political rollbacks in Hong Kong. But if the US does not stand with Hong Kong, where China has clear international obligations, what of Taiwan? Will Peking, noticing that Hong Kong has been permitted to slip away without a struggle, now believe it can use military force to retake the island? Why should Taiwan, in such circumstances, heed American advice for patience? And what of Japan, which hopes for a Pacific in which no single power will be dominant? Will it continue to believe the Americans will keep their word? A senior American diplomat told me recently that if “Hong Kong goes bad, Taiwan will go its own way and the US will find itself all alone in a big black hole in this part of the Pacific.”

For all their warning about the Chinese military buildup, Bernstein and Munro agree that China will not soon be able to confront the United States militarily. In the meantime Peking’s leaders will be watching to see if Washington will blink as Peking tightens the screws on Hong Kong. They will wait to see if Washington’s negotiators are more likely to take a stronger stand over Hong Kong than they are over Chinese sales of weapons to Syria and Libya or poison gas to Iran. In Hong Kong I have the impression that Chinese officials and their local allies were startled by Consul-General Boucher’s firm statement, especially his warning that Washington “expects” China to fulfill its promise of a high degree of autonomy to Hong Kong’s open free society.

But strong statements are effective only if they indicate a readiness for stiffer action, the kind foreseen in the US-Hong Kong Policy Act, which says the president may suspend laws applying to China if Hong Kong’s autonomy is sufficiently impaired. Of course no American act, such as trade sanctions, should harm Hong Kong itself. But an effective list of possible retaliatory measures (which in accordance with “constructive engagement” could be discreetly explained to Peking) should include delaying the exchange of visits between Presidents Jiang and Clinton, annual review of Most Favored Nation status, which the Chinese badly want, and delay of China’s entrance into the World Trade Organization. When he visits Washington later this spring, Mr. Tung should be left in no doubt about American concerns.

These concerns about Hong Kong need to be made particularly plain in post-Deng Xiaoping Peking, where the leaders and the aspiring leaders are caught up in their own power struggle and would find it no less politically risky to loosen China’s hold on Hong Kong than its control of Tibet and Xinjiang. No doubt some of these politicians would like to make Hong Kong an example of successful Chinese control, testimony to the view that there is something in the Chinese character inimical to pluralist democracy and too volatile to be governed by anything but a supreme leader or group of leaders.

After living in Hong Kong for several years, I doubt a large number of Hong Kong citizens will submit quietly to that view. “Few Hong Kong residents will choose to deny their ‘Chinese’ ancestry,” Yale’s Professor Helen Siu recently pointed out in a speech.6 “But if estimates were right—that one out of every six persons marched in the wake of the 4 June incident—…it will not be easy for the Chinese government to claim their cultural identity or tempt them with purely economic gain.”

China cannot in any case promise cultural identity or economic gain to Hong Kong. The first has long been established and the second is beyond Peking’s gift. A spokesman for Mr. Tung told me recently, “They’re paranoid in Peking, you see. They thought Tiananmen was the Cultural Revolution all over again. When Hong Kong people hold vigils for Tiananmen every June 4, Peking sees that as the Cultural Revolution. People here have to learn to restrain themselves a bit until China catches up.”

This is nothing more than a sophisticated justification for oppression—and for the policy of “constructive engagement.” What Peking leaders want in Hong Kong is complete control. They themselves were once part of a small group of conspirators determined to change China, which they now regard as theirs to govern. They seem equally determined that whatever changes China undergoes in future will not start in Hong Kong and that the Asian nations will see Chinese power inexorably and efficiently asserted there.

America’s foreign policy invariably contains a moral component; and once the country undertakes clearly defensible moral obligations, failure to fulfill them has inescapable consequences. If we do nothing about Hong Kong and ignore China’s own clear pledges, Americans will have visibly failed themselves and disappointed the peoples and nations who look to them for leadership and democratic standards. If he is not to disgrace his country and his presidency, Clinton must hold to his pledge that the US will stand with Hong Kong’s democrats and their free institutions.

—March 27, 1997

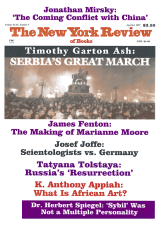

This Issue

April 24, 1997

-

1

Lucian Pye, “An Introductory Profile: Deng Xioping and China’s Political Culture,” in David Shambaugh, editor, Deng Xiaoping: Portrait of a Chinese Statesman (Oxford University Press, 1995), p. 4.

↩ -

2

They finished their book before the recent allegations that the Chinese government has sponsored attempts to funnel contributions to the Democratic Party in order to gain influence in the White House and Congress.

↩ -

3

Andrew Nathan of Columbia University, a great exponent of human rights and democracy in China, and Robert S. Ross of Boston College, in their thoughtful new The Great Wall and the Empty Fortress (Norton, June 1997), are far more optimistic that China can be reasoned with than the authors of The Coming Conflict. Nathan and Ross believe China’s military to be “the most backward among the great-power armies in East Asia, vulnerable to military challenges in its coastal waters, unable to win an air war against Taiwan, and unable to project power to defend its territorial claims.” Because of its inadequate military resources China cannot “establish regional domination” in the foreseeable future. But Mr. Nathan and Mr. Ross also see China as “a spoiler,” a disrupter of its neighbors’ security and of attempts to create regional and global orders. China, they conclude, is in many ways a vulnerable power, especially internally and even more so after the Deng era. Understanding this vulnerability and even insecurity—which can make it dangerous to its neighbors—”should help Western policymakers accommodate China when they should, persuade China when they can, and resist China when they must.”

↩ -

4

The authors say that China “probably has the largest number of political prisoners of any country in the world—it has officially admitted to three thousand.” Peking almost invariably says it holds not a single political prisoner, and that prisoners like Wei Jingsheng and Wang Dan are criminals. Organizations like Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch put the number of political prisoners much higher. In any event, since the legal process in China is a farce it is impossible to say who is not a political prisoner.

↩ -

5

Routledge, 1996.

↩ -

6

Published in Index on Censorship 1997 (January/February 1997).

↩