Murray Kempton wrote about eleven thousand newspaper columns in his time, and, like all practitioners of the trade, he devoted a fair percentage of them to the deflation of the pompous and the unmasking of the fake. Early in the campaign of 1992, he determined Bill Clinton to be a disappointment to integrity and the Democratic Party, and so Murray moved toward his Maker still sticking fine pins in the President’s bloviated self-esteem; it was with a healing smile that one read of Bill and Hillary’s declaration to the wire services of their heartfelt sadness at his passing.

But unlike most of his colleagues, Murray Kempton did not rise in the morning with the desire to attack. Part of what made him unique as a newspaperman was his impulse for praise and forgiveness, his pleasure in shining a light of glory on a legitimate hero (on Mose Wright or Adlai Stevenson) or, more difficult, to find a particle of worth in reputations routinely trammeled. He found instruction (if not glory) in Dave Beck and Jimmy Hoffa, Richard Nixon and Jean Harris. Were not their failings, their greed and jealousies, the failings of us all? Like Chekhov’s stories, Murray’s dispatches were finally about weakness, desperation, forgiveness, losing, and love. His technique was to begin with the immediate and the local—a shooting, a trial, a strike—and end with a greater speculation. When writing, for instance, about the myriad political misjudgments of Paul Robeson, he wondered if perhaps Robeson “was, at the end, one of those of us who turn back to our youth because it asserts itself in clouded memory as purer and freer of spite than pretty much everything we have met since. It wasn’t of course; but what else are we old men to do?”

Murray Kempton grew up on the left, but he was predictable only from a moral—and never a political—point of view. Which is to say he had no “character issue.” He was always dubious of the self-appointed saint pretending to absolute virtue. When Carmine DeSapio finally lost his municipal throne in September 1961, Kempton spent that election night at the side of the fallen Tammany king and finished his column with an arch warning against the pretensions of those masquerading in the cloak of reform. He describes how he took leave of DeSapio that night and “walked into the streets and noticed that there were no slums any more, and no landlords, and the Age of Pericles had begun because we were rid of Carmine DeSapio. One had to walk carefully to avoid being stabbed by the lilies bursting in the pavements. I wish the reformers luck—with less Christian sincerity than Carmine DeSapio does. I will be a long time forgiving them this one.”

There was, of course, high comedy in the way Kempton could pretend to find the redeeming feature in every low scoundrel: “Matthew Ianniello has been lost to Mulberry Street and on long-term lease to the federal prison system since 1986, and where are the scungilli of yesteryear?” Ianniello was a racketeer and a restaurateur in Little Italy who had “standards rare even for the respectable,” but now that he was in jail the sauce at Umberto’s had “lost its magic; the hot tasted like the medium, and the medium tasted like the sweet, and the sweet held no promise worth stooping to.” While the rest of the press exploited the Mafia for its easy narratives and saucy colors, Murray saw them as men of crime but who somehow, because they could not sue for damages, were blamed for everything. He accorded them a wry and stylized regard. Similarly, he withheld a too-easy regard for the self-righteous. Mario Cuomo, who always credited himself a vessel of civic virtue, once called Murray’s colleague at Newsday, Sydney Schanberg, and asked, “How do I get Murray Kempton to love me?” “Governor,” Schanberg replied, “why don’t you try getting indicted?”

Murray Kempton enjoyed toying with no character in public life more than he did with Murray Kempton. His projected self was no less distinctive and comic than that of Chaplin’s Tramp. Hapless and courtly, he bicycled his way through late-twentieth- century New York while the rhythms of Purcell and Gibbon played in his head. In a story called “My Last Mugging,” he described being held at knifepoint in his neighborhood around West End Avenue by two junkies he quickly thought of as Mutt and Jeff. Unfortunately, he had almost nothing with him:

I took out my wallet and showed it to them with an anxiety to please that, at the moment, at least, had curiously less to do with the knife than with the recurrent sense of my own inadequacy on social occasions. I felt like a welsher. They had done their job; they had pulled a knife, such as it was, and quite enough for me; and I wasn’t doing mine…. It seemed entirely proper to apologize.

“Gentlemen,” I said at last, “I feel like a shit.”

“Don’t you think we feel like shits?” Mutt answered. “We don’t like to do this kind of thing. All we’re looking for is a couple of bucks to get a shot of dope.”

Where I live, we are rather stiff-necked about permitting someone else to claim the moral advantage. They turned and left the lobby, with Mutt trailing the knife slackly against his trouser leg, the whole night yet before him and without the will to recover from the first mischance.

I felt the sixty cents still in my hand and called after them, “Well, anyway, take the change.”

And Mutt came back and took it, and we said good night, and I went home with no sense that I had made it up to them.

Fortunately, no columnist I know of has tried to mimic Kempton, for it would be impossible and a terrible embarrassment to the imitator. His is the syntax of someone who has absorbed with equal passion Proust, Mencken, the Earl of Clarendon, and the Book of Common Prayer. He could write about the Mafia with such brilliance because he knew his Machiavelli and Dante as well as he did the collected wiretaps of Simone Rizzo DeCavalcante. He knew his way to the library as well as to the Ravenite Social Club. He could write about Jimmy Hoffa because he began life as an organizer for the ILGWU and as a labor reporter at the New York Post alongside Victor Riesel. His book on the Thirties, Part of Our Time, is a classic not least because of his own experiences as a young man with the Communist Party. In his late seventies, he could write about the world of rap and Tupac Shakur not least because he had known Tupac’s mother, Afeni, a lifetime ago when she stood accused of robbing banks with the Panthers.

Advertisement

It is usually too much to ask of a columnist to break down the arguments for or against Earned Income Tax Credits or a new amendment on the reform of northern fisheries. Nine hundred words and a daily deadline do not leave much room for error or explanation. Murray Kempton could do infinitely better than that. He could do what only a few writers of any age can do. He could change your life. He wrote about character and its pursuit; he did it so convincingly, from the core of himself, that no less an authority than Anthony (Fat Tony) Salerno once passed along the ultimate compliment, that “Roy Cohn always stated that you were an honorable man.” And so he was.

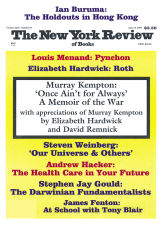

This Issue

June 12, 1997