An Explanation of My Title: Historical scholarship, that ragbag of myth, holds that once in 1927, while recording at the Columbia Studios, Bessie Smith had run through all her prepared material and then found herself with enough time left for another song and no way to use it except by making up the lyrics as she went along.

The result was “Lost Your Head Blues” and one of Bessie’s supposed improvisations was:

Once ain’t for always

And two ain’t but twice.

The beauty of the lines was inexplicable and so was their meaning. Exegeses of Bessie’s work have always tended to err in the direction of the coarse; and we pursued the mystery of the import of these words for the longest while among esoterica of sexual reference far beyond our own puny experience.

But we never solved their puzzle; and it teased me into late middle age until suddenly I understood. Bessie had meant to speak not about some unfamiliar variety of sexual congress but about a human condition that, if it is not universal, has inescapably been my own.

To say that once ain’t for always is to remind us that to have done what we ought to have done is no assurance that we will do it the next time we ought and that to have left undone what we ought to have done is no condemnation to the leaving of all future oughts undone.

“Lost Your Head Blues” has since resided in me as the revelatory text for a life history that has been a continual process of confronting and suppressing one bad part of my character and then finding and struggling to suppress quite another bad part on and on and probably unto the last breath.

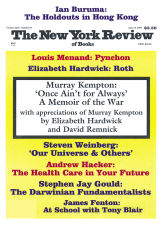

Now it has occurred to me that I may not be alone in this condition and that it might, as Clarendon put it, be not unuseful to the curiosity if not the conscience of mankind to attempt a memoir each of whose chapters would record some new discovery and transient overcoming of another deformed aspect of my nature. That is what I will try to do if the Lord has the kindness to allow me time to complete my recitals of successive combats with devils who once surprised with their newness and are now old and apparently old, gone, and replaced. Only His hand can finally spare me from unexpected encounters with some next one.

I came back from the war with nothing scarred about my person except a cartridge clip shot from my fatigue trouser pocket north of Bataan in February of 1945.

In the years before its disappearance I would occasionally happen upon it in a bureau drawer and be reminded less of how close life’s wounds scrape than how unaware they take us when they do.

We had been whiling an afternoon away in a firefight where we had, as amateurs do, been wasting our stocks of ammunition, and a squad of Japanese stragglers had been, as professionals must, disciplinedly conserving theirs. Now and then we would subside from our clamors, and one of them would fire a single round to set us off again and advance the hour when we would have used up our stores and be forced to let them be.

Somewhere in the midst of these futilities, I felt a light slap, smelled smoke at my haunch, and looked down to see the .45 caliber cartridges ascending and scattering from my side pocket. If you make the most of the noise long enough, you settle into the delusion that there is no one in the room except yourselves.

And so I at once took it for granted that someone in our troop had shot too close from my rear and yelled out to straighten the line. A Philippine scout as raw as we and fatally more anxious to please stood up to obey my unfranchised command, was shot under the eye, and fell among his brains.

The work of the day went profitlessly on for another hour before his comrade scouts picked up the body and carried it for deposit upon the bamboo porch where his mother was standing. He had died the soldier’s death in a war scarcely half a kilometer from the ground where he had learned to walk. I told the mother and brothers and sisters around her that he had been brave. All he had been, of course, was dumbly respectful of a thoughtless, hasty, and unauthorized order. I also said how sorry we all were, which commonplace and guilt-unconscious nicety could hardly, since I had no Tagalog, have reached her there among the mute and immutable sorrows of the East.

Back at our outpost, I looked at my violated cartridge clip. Its lips had been parted so neatly as to give free play to its spring. The top cartridge must have exploded, which would explain the clap and the smoke. The shot had then come from the front and would near to a certainty have passed by unnoticed if it hadn’t struck this piece of metal jutting out too far behind my own flesh to have served it for shielding.

Advertisement

We spoke of the dead scout that evening with too much more sentimentality than sentiment, and then so far forgot him as not even to wonder about the funeral where we might have formed a useless but not unfeeling guard of honor. He had died to make no difference between his freedom from harsh but seldom-seen conquerors and his deference to callous liberators it had been his misfortune to understand too little and to trust too much.

We would soon forget everything about him except the startling ruddiness of the heap of his brains. Young men are careless people and never so much a danger to themselves and others as when most of what they are seeking is relief from boredom.

For what else but boredom could have brought me to such engagements uncompelled by the will and irrelevant to the desires of my commanders and driven to them by that least bearable of boredoms, the one that turns life to lead for those who feel denied every function of use and value?

I had come to the South Pacific doubly deprived of purpose because my military speciality and my assigned duty had already withered into obsolescence. My training had been as a radio operator assumedly equipped to send and receive International Morse Code at a speed of twenty-five words a minute. My wrist was stiffer and my fist infirmer than this rating attested; and these disabilities might have troublesomely betrayed themselves if the continuous wave transmissions of dots and dashes had not been outmoded by voice radio awhile back.

Since the Signal Corps had so small a residual need for my superseded skills, it could not be blamed for shuffling me off to its even-worse-superseded ground-observer service. There had existed an age when the air spotter had been a valued instrument for early warning of a hostile flight’s approach and had occasionally earned himself a modest portion of legend. But the development of radar had long since pushed him nearer and nearer to wherever the observation balloon had gone before him.

Even so radar had its blind spots; and ground-observer teams went on being deployed to points of isolation on the unlikely chance that some Japanese plane might fly between mountains and hedgehog over peaks and so conceal itself from the radar’s beam that only human eyes could detect it. It was so hard to take pride in having no excuse for being except as insurance against all-but-inconceivable circumstances that I took to self-identification as “Forward Observer attached to the Air Force,” a desperate essay at being mistaken for those artillerymen who had something real to do and did it under conditions that could stand a man’s hairs on end. Everyone else with a title to dignities larger than our own went on speaking of us as “groundhogs.”

It did not take long, for the burden of being survivor and relic not just of one but of two of the auxiliary arts of warfare so weighed me down with my uselessness that I took to bobbing up whenever two or three were to be gathered together for adventures lurid as anticipation and pallid as experience.

For awhile at Lae in New Guinea, I took to patrolling with an Australian Sixth Division squad fleshed out by veterans of the European Theater. Two or three among them had been harried from Greece through Crete and at last turned fiercely to bay in North Africa. Then, having followed and endured the gloomy Anzac destiny of profiting the Empire’s interests more abundantly than their own, they had been recalled to face up to the Japanese advance upon their own home continent.

They had walked from Port Moresby over the Kakota Trail and down toward Buna, formed themselves as though on parade, and, singing “Waltzing Matilda,” marched straight forward until the Japanese opened up from the embankments that would be as close to Australia as they would ever thereafter go. Whatever the case, such was the legend, told, as always with the Aussies, by others than themselves. The reality was sufficiently superb, for in that week, the Australian Sixth and the American 23nd had won the Battle of Buna and decided the New Guinea campaign two years before I threw my feather’s weight into the balance.

My Aussies knew that their business was done, that they were indisposed to further goes, and had settled into nights of reminiscence and days of desultory patrols, whose unoffending objective was to remind the enemy’s leftovers that they were beaten and would be senseless to act otherwise. There are more fruitful ways to pursue the illusions of adventure than with companions who have already nobly undergone the destruction of most of their own. And so we spent our days scouring for nothing; and I can barely recall sensing, let alone confronting, a foe armed and dangerous.

Advertisement

My comrades could have taught me all manner of craft; and I have no doubt that they would have handsomely done so if some laboratory exercise had been forced upon them. As it was I picked up only two lessons. One was never to set forth for marsh or crag without first shining your shoes. The other was what I came to think of as the “Lick.”

I noticed early on that each of the squad’s elders had the habit of touching some part of his body—usually the crotch or abdomen—before entering some spot of brush where insecurities might hide. Later on, when I had strayed into patrols less secure against hazard, I caught myself now and then sweeping my hand across my forehead just above the eyebrow and could fairly hear the interior voice whispering that, if I were not hit there, I would be hit nowhere. And then I understood the tic for what it was, the talismanic gesture that restores the delusions of invulnerability and is the faint suggestion of recoil that defines the countenance of the him or the her who has known the supreme crisis.

I have recognized its look on the face of a woman just after her first child has been born and as surely I have marked it upon the drunken soldier with his forged leave pass and have noted his distinction from the arresting MP half again as tall and with his traded-for or extorted paratrooper boots crowing on his feet. From then on I understood that what had conveyed me to these wanderings had not merely been boredom but an almost possessed desire to earn that look and some lodgement with those who had been there.

To have departed ashamed of myself from as many places as I had before and would again had bound me as with iron to the need to leave this one at least without cause for apology. We always must of course, and so too would I soon and three times over, once for cowardice, once for the coarsest breach of the decencies of warfare, and a third time that would have been worse than either if I had not been summoned back from its almost overmastering temptations just in time.

And so, from dreams of being more than I could ever be, I went on volunteering for anything that was not kitchen police and, for what now seems to have been an eternity, I was cheated in each and all.

The B-17 crews gave me leave to ride a few times on their bomb runs to Wewak, whose official status as last bastion of the Japanese air arm in Australian New Guinea was already dissolving into an abstraction. I would sit at the .50 caliber machine gun station in the belly turret with naught to challenge and little to enchant me except the vistas of the coral seas.

I further played my spectatorial part in five or so assault landings upon beaches so obscure that most of them slip by without mention in the shorter histories of the war and even I cannot say for sure how many they were.

Upon discharge I was issued five campaign ribbons, three of them with the arrow that signified—and in my case oversuggested—repetitive encounters with hostile beachheads. One such arrow certified my service under conditions of combat in the Admiralty Islands, which I had never seen. But then the army is never so generous as with compliments that cost it nothing; and my papers credited me with ten D-Day landings, four of them over and done with while I was yet stateside.

But then, if I had indeed played these four fictional roles, it is hard to imagine them as much different from the routine our commanders would never vary and our enemies could never interrupt. We would tune our radios to a Japanese frequency that as usual told us precisely where we were going and as always promised to redden the seas with our blood when we got there. We would bed down as well as we might against bulkheads neither tropic air nor moonlight could soften until we made our half-slumbering way down the rope to the landing craft.

Military convention had fixed our appointment for two hours after the infantry’s first wave. The wait was a spectacle whose gauds never ceased to delight, with the great cruisers—we never rated a battleship—grumbling behind us and the little destroyers firing the streams of their rockets into vacant beaches. Then, as though to announce the break of day, the B-17s would let loose their bombs for majestic descent in orderly stacks into trackless forests while the infantry fanned out no farther than it needed to establish room for an airstrip, a communications system, supply tents, a hospital, space for the Salvation Army’s doughnut wagons, and like necessaries for this way station to the next leapfrog in General MacArthur’s vision.

We would debark to the anticlimax of flailing our shovels and tools against the coral and contriving foxhole enough to shelter us for a night’s sleep before being told, as we quite often wouldn’t be, what we were then supposed to do.

No image from these undifferentiated excursions has kept so vivid an impress in my memory as one from a half-lit morning off Sansopar when I was sitting in my stall in the landing craft and reading Victory. I had arrived at the passage where Axel Heyst, beset by peril on presumably civilized premises, remembers “with regret the gloom and the dead stillness of the forests at the back of the Geelvink Bay, perhaps the wildest, the unsafest, the most deadly spot on earth from which the sea can be seen.”

I looked up and there before me spread the forests at the back of the Geelvink Bay, wild and gloomy and still as the tomb to be sure yet all else but unsafe for me in my armor-surrounded immunity. No other moment in New Guinea drew me so close to an epiphany; and yet, having been received as it were on loan from Conrad, it was not enough my own to realize fulfillments more complete than those quasi epiphanies accessible to any tourist with his guidebook.

And so it was as tourists still that we debarked upon the Luzon beaches off the Lingayen Gulf in January of 1945. We arrived, however, heartened by prospects of employments less empty than had been our lot. The air force had at last taken account of the inanition of its ground-observer teams and thought to change their duty to voice radio guidance for the fighter bombers in their works of close support for the infantry. We would transmit the grid coordinates of enemy positions to pilots who could then match them with their own flight maps and avoid mistaken inflictions upon our own troops.

These chores were sufficiently simple to accord with the generally low estimate of our competence; but they offered our first promise of actual service as far as, if no farther forward than, a battalion headquarters. We had even been indulged with a dress rehearsal directing P-51 sorties around the road to Bagulo and escaping serious damage to our credit.

But our sentence to limbo was not yet commuted; and we docilely resumed the ground observer’s otiose existence and went down the road toward Mazilla and stopped at Aglao to mount guard against the improbable apparition of a hostile plane that had eluded the radar’s notice and might take the advancing infantry unaware.

We were welcomed as liberators by the first authentic civilians to speak to us in the past thirteen months, established our outpost in their barrio’s most impressive hutch, and began keeping our object-unrewarded watch around the clock.

One early evening—our third in office—one of our new neighbors came on the run to report that he had sighted a full Japanese company half a kilometer away and grouping for an attack on Aglao.

There were four of us Yanks and at least fifteen Philippine scouts, the makings of a respectable garrison. We nonetheless panicked like so many tourists, stammered our excessive alarms in a message to the rear echelon, shot up our radio, snatched our codebook, and scuttled a full kilometer down the hill followed pell-mell by scouts overdependent on the leadership of Americans who could display no more inspiring symbol of leadership than the spectacle of their heels in flight.

We spent a haunted night in the brush until the sun was high enough to embolden us to sneak back to Aglao. We found her peaceable as ever and all our stores pillaged to the last K-ration can and all but the last thread. We had been well and thoroughly set up. The only enemy in the neighborhood had been the cunning hidden somewhere beneath the fair face of our welcomers.

We had earned ourselves a court-martial and would, I suppose, have gotten one if persons of substance had mistaken anything we did for stuff that mattered for good or ill. The rear echelon sent up a new radio and a fresh stock of rations and spared itself the bother of reproaches. We had been relieved of every inconvenience except the ignominy whose weight bore down upon each and all of us ever present and never spoken of.

Our looters had overlooked one of my shirts; and, since to ask supply for a reissue of clothing would have been to call further attention to my shame, I had to make do with that shirt and the one I had worn on that night of worst disgrace. And so the discovery of the little I would ever know about war was carried through with two shirts, one pair of fatigue trousers, and the last pair of socks that I would wash and let dry every night while I stood my watch barefoot.

If the war had ended that night, I doubt that I could thereafter have found stomach to mention my part in affairs that, after continually denying me all opportunity for tactile experience, had finally deprived me of all dignity. But life sometimes blesses us with reprieves; and, having encumbered myself with dishonor fleeing a fantasy of the Japanese, I would find a kind of redemption running away from the fact of them.

A squad from the 38th Division set up in Aglao the week after our debasement; and we joined its daily patrols in company with the scouts. Our searches brought us into five or so skirmishes, bloodied only twice on our side and, so far as I can judge, only once on theirs.

The Japanese had lost their corner of the war and were much too shrewd at cover and concealment for us to catch them unless boredom impelled them to stand and fight. I have often wondered why they cared. Perhaps it was the itch to instruct.

They were the only authentic, because the most fully completed, soldiers with whom I would in my dealings ever reach intimacy; and no apprentice could ever want for better teachers or reasonably expect to stay alive with ones less meagerly equipped with armament.

They closed school on us one afternoon in March just after we hit upon a straggler scrounging in a comote patch. Our leadman shot him and he stumbled and presumably fell in a grove. We were too cautious to follow since one of him argued more of them; and we moved up to a hill overlooking a rice paddy and stretched ourselves prone in the skirmisher line.

And then just down and to our left we saw a Japanese soldier carrying on his back the comrade we had left wounded, and all down the line we opened up on him. There were at least twenty meters between him and any cover at all; and he walked them like a farmer at his plow with all that metal hurling death around without ever straining beyond the solemn and deliberate majesty of his stride. My war was not overabundant with specimens of bravery in its purest essence; but this one will do for a good many.

He kept walking and we kept firing enough to leave him dead ten times over and we never hit him once. Some guardian angel had saved us from the ultimate infamy of killing a soldier carrying a wounded man off the field. I am no witness to the end of this one’s trek, because we noticed two others setting up one of those rickety-ticky Japanese machine guns across the way and turned our weapons toward them. And then the ambush was sprung.

It was work of the highest art. They had used the interval of our malevolent distraction to emplace snipers in the trees behind and they were firing at us from the rear with reports so close and loud as to make me think that they were using my shoulder for a gun rest. The machine gun commenced to tap like a woodpecker; and we took our departure with sufficient discipline to pick a route for the rout as near as we could keep to the foliage at the rice paddy’s border.

I was next to last in the line of retreat with the Browning Automatic rifleman behind me; and I ran while that silly machine gun putt-putted behind me and the two carbines fairly burst my eardrums from overhead and the little shots were splitting apart when they hit the grass around me, until I at last fell gasping behind a tuft of cane stalks.

It was only fifty yards to absolute safety; and I was familiar enough with the woodpecker to know that its gunners could only fire five times before having to stop and push the drum back in order to start again. The full limit of demand upon me was to stay low, count five putts, and then get up and run ten or so yards toward total security. The gunners dealt their ration from what sounded like an increasingly comfortable distance; and then just as I was picking myself up for another dash, the BAR man called out that he had been hit.

The last minute or so had been consumed with desperate efforts to seem invisible to everyone behind me; and I dedicated the next ten seconds to seeming deaf as well. I lay there fixed in denial that I had heard this voice in its distress. I was in that moment as quit of the war as if the copy of my discharge papers had lain for a century in Washington’s files. My vow to go home with no grounds for apology had already been twice violated; and I should surely had done it a third time if the BAR man had not cried out against that awful silence, “Oh, don’t go away and leave me.”

No words other than those particular seven could have brought him my help or me some shoring-up of my honor in its ruins. But these served for the miracle of taking me back to where seconds before I would not have gone for God or man; and, when I went to see what might be done for him, I covered the distance erect and uncaring what the enemy might see in the numbed conviction that my life was now forfeit anyway.

His wound was in the right thigh and none too bad a one; but he was too damaged to walk and too large for me to carry. I fiddled with fingers scarcely more practical than sticks to mount his BAR and contrive some impression that he was yet fit for combat, wished him a peaceful wait, and, without time to waste with deals of concealment, I ran across what no longer resounded as the field of one-sided fire and down the trail to find bearers stronger than myself.

I found my comrades in a commendable condition of calm, and explained why we would have to return. They prepared to follow me without a flicker of dubiety; and before we went, I handed my Thompson machine gun to a scout and took his carbine instead. The Thompson had been my talisman; to watch the arc of .45 caliber bullets exiting its muzzle was to feel safe and shielded from all man’s malice. The carbine had no such claim on reason or superstition; but neither was of consequence by then and even weaponry wasn’t, because I knew to a dead certainty that here was the hour of my last breath. The carbine’s point was that it was lighter than the Thompson; a twig would have been better still.

We made our way through the heaviest of silences upward to where his mates gathered up the BAR man while I stood with my rifle pointed across that lately dreadful field in a counterfeit of the protective cover I had lost the will to provide. I had simply become a target. The enemy across the way let us be; the twenty minutes that had begun with our coarse denial of all gallantry toward one of them was ending with their free and easy tender of chivalry toward one of us.

A while afterward I came upon those pages where Antoine de St. Exupéry recalls his flight on reconnaissance to Arras to observe and report on the deployments of the French in a place from which the Germans had already driven them. He had come down for a closer look at the lines and, as he descended alone, naked and surrounded by the puffs from the antiaircraft guns, he became suddenly aware that war is the acceptance of death.

So I had lived once in that state of acceptance in that unforgettable paddy near Aglao and it would never happen again. I took to wondering how many occasions before the fatal last are allowed a soldier for feeling all his sensations distilled into those of the target that can no longer act for itself but only wait for death to dispose as it chooses. Once in hospital—for jungle rot—I put the question to Sergeant Herman Boetcher, a great soldier indeed; and he answered that he well knew the sense of the accepted death because he had undergone it five times. A few weeks after he came out of hospital, I read that he had been killed. So the limit for acceptances of death is perhaps six.

By sunset back in Aglao we were surprised by how much light we could make of the afternoon. There is a curious spiritual uplift in being done to so delicious a turn. The BAR man had been hurt just enough for a chance to go home and none of the rest of us was the worse for the day. We laughed more delightedly still when word came that the Japanese were walking guard formation in their renewed pride not a hundred yards away. And so they were, or anyway one of them imperturbably was, more than a hundred yards off but well within .30 caliber range.

I am embarrassed to confess that I did not render him the salute that was his due.

There could not have been more than six of them and there were never fewer than twenty of us; and our advantage in metallic weight was far crueler than in numbers. I myself carried more killing power on my shoulder than all of them could summon up with their .25 caliber single-shot carbines.

We had been taken by surprise but we had not entirely lost our heads; and it would be by no means unreasonable to inquire why, instead of withdrawing in order, we did not respond as patrols are expected to and simply turn our weapons on these overmatched enemies and transform their ambush into their terminal disaster. I have once or twice asked myself the same question. Respect for our betters perhaps; and in any case rather more than just as well.

They had made out of us the stuff of what must have been the last clear Japanese victory in the Pacific, and they deserved the satisfactions of a pride that had outlasted what may or not once have been their arrogance.

I recovered my Thompson and some of my aplomb; and we returned to our patrols the next day and for a week or so and, outside of an indecisive brush or so, never intimately engaged them. It was now near the end of March and we had been more than two months in Aglao. The normal span of our languid duties was D-Day plus 19. Our very existence had been forgotten; and, for two or three days, we went so far as to close down communications with net control and take off like the addicts we had become to join our old fellow travelers from the 38th on patrols around the Wewak Dam.

At last we were recalled to headquarters. I came down out of the hills as one who, while in no sense a tiger, had feasted and been near feasted upon by tigers and would never be the poor thing he had been before. I told myself with entire assurance that I had for all time to come dammed and copper-lined the turbulent bank-caving river of my life and that I would never again flinch or flee from anything and that, most especially, I would never go away and leave anyone. It had been true: once ain’t for always.

But it is a truth with two faces. One of them looks back and is a consolation. The other looks forward and is a warning. We had been back in the rear area for no more than a week when the sound of the guns awoke me in the night and I came out of the tent to see the little white tracers that identified what had to be the last airworthy Japanese Betty in the whole of Luzon. If I had really been what I thought I had become, I would have gazed serenely at her futile gallantry and tried to conceive whence she had come and to where she could possibly return. Instead I surrendered to my old thought-conquered self and scuttled in aimless terror from tree to tree. Once indeed ain’t for always.

I knew then that timidity and, yes, cowardice would be the permanent tenants of my interior and that I could never hope to trust my courage and would have to settle for preserving my dignity, a virtue whose keeping depends upon constant care to protect it from takings by surprise. It would be some years more before I discovered the equal worthlessness of my assurance that I would never again go away and leave anyone.

This Issue

June 12, 1997