I grew up in the 1950s in Wexford, on the southeast coast of Ireland. It was a small town with a history. Here, in the twelfth century, a gang of Anglo-Norman robber barons, seeking land and Lebensraum in an as yet unplundered territory, had made the short sea-crossing from Wales and set up an enclave which they were to defend with unflinching tenacity in the face of an outraged but disorganized Irishry and a suspicious and jealous English king. So was inaugurated that connection between Britain and Ireland which was to bring eight hundred years of troubles to these islands, troubles that are with us to this day. There are historians who argue that, ironically, it was not greed that impelled Henry II of England to take control of Ireland—the English Pope Adrian IV had, with characteristic papal insouciance, “granted” the island to him in the bull Laudabiliter in 1155—but fear that the Norman lords would set up a power base on the other side of the Irish Sea from which to challenge his authority. Thus, stumblingly, does history blight the generations.

Every summer in that postwar decade of my childhood my family would decamp to the seaside resort of Rosslare, some ten miles south of Wexford, where we would spend a month or six weeks huddled in a rented wooden chalet consisting of two or three rooms, with scant bathing facilities and an outside lavatory (one such accommodation was a wheel-less railway carriage set down in a corner of a field: utter magic for a small boy). The Fifties were a straitened time in Ireland, as it was elsewhere in Europe, and we were lucky to be able to afford this annual holiday. In my memory of them these summer weeks are bathed in a golden light, the effect no doubt of lapsed time rather than the Irish climate. One event, however, generated a particular and inimitable glow. This was the Protestant Church of Ireland summer fête. It was held in a tussocky field adjoining a venerable and rather pretty stone church. Here, on trestle tables, would be displayed for sale the products of polite endeavor: homemade jam, pots of honey, bunches of vegetables, cakes, tarts, hand-embroidered table napkins, all laid out in cheerful, confident disorder.

I never missed a fête day. I would go there by myself, and tell no one where I had been. This secrecy was due partly to an unwillingness to share this magical event with siblings or friends, and partly to an obscure unease. As a child of the Catholic lower middle class, I regarded Protestants with a mixture of apprehensiveness and fascination. In those days, in our Republic, which was, as it still is, 95 percent Catholic, we were forbidden to enter a Protestant church under pain of unspecified consequences. It would have been possible, at our level of society, to go through an entire childhood without ever having met, knowingly, one of our “separated brethren.” But what splendid specimens they seemed to me, these brisk, equine ladies in their flowered frocks, and kindly-eyed gentlemen in brogues and “good” but threadbare tweeds, languidly celebrating their annual fête galante. I might have been among the gods. I imagined them, at day’s end, bumping in their shooting-brakes up the long avenues to their ivy-covered, many-windowed mansions, where already the servants—kinsmen and kinswomen of my parents—were lighting the candles and setting out the canopied dishes for dinner.

Afterward there would be port, and games of bridge, and desultory conversation by the fireside. Then one among them would rise and “retire to his study,” there to take up his pen and add another few effortless paragraphs to his journal, or write a witty letter to The Times, or finish off that never to be published essay on trout fishing, or the Gallipoli campaign, or the influence of the Brehon Laws on medieval Irish bardic poetry. And if I were back there now, in that lost Rosslare of my childhood, I could put a face to that imagined figure leaning at his lamplit desk. The face would be that of Hubert Butler.

This humane, elegant, and subtle writer was born in Kilkenny in 1900, and died there in 1991. His people had been part of the first wave of English settlers who arrived in Ireland after Henry II’s annexation. The Butlers were one of the leading Anglo-Irish families, mutating with time into the Dukes of Ormonde who maintained vast estates and built Georgian Dublin. Hubert Butler, although always quick to point out that his family was a very minor cadet branch of the dynasty, was proud of his name and all that it signified; he founded the Butler Society, and was an assiduous editor of the society’s journal until his death in 1991. Like many of his class, he was educated in England, at Charterhouse and Oxford. Returning to Ireland at the end of his college years, he worked in the Irish County Library Service, one of the great civilizing institutions of the new Free State of the 1920s. Later, in the Thirties, he traveled widely in Europe, and worked as a teacher of English in Egypt and Russia. In the mid-Thirties he spent three years in Yugoslavia on a scholarship from the London School of Slavonic Studies.

Advertisement

When his father died, in 1941, Hubert Butler returned to live in Maidenhall, the family’s modest but handsome Georgian house set amid the rich pasturelands of County Kilkenny. A few years later he revived the Kilkenny Archaeological Society, an influential group in Irish historical studies that had lapsed for half a century. He was a fine linguist, and translated Leonid Leonov’s The Thief (a perceptive essay on Leonov is included in Independent Spirit), and Chekhov’s The Cherry Orchard, a translation still regarded by many critics as one of the finest English versions of this play.

His main literary legacy, however, is the body of essays on a wide range of subjects, written over some sixty years for newspapers and magazines (although some pieces remained unpublished in his lifetime, and seem to have been written simply for the pleasure of the exercise) but not gathered into book form until 1985, when Escape from the Anthill, the first of four volumes, was published by the Lilliput Press in Dublin. For this endeavor, the world owes a debt of gratitude to Lilliput’s director, Antony Farrell, whose energy and enthusiasm spurred Butler to agree to the assembling of these wonderfully rich and stimulating collections, from which the essays in the anthology under review have been selected.

Hubert Butler was a very particular kind of Irishman. He liked to describe himself as a Protestant Republican, but the historian Roy Foster has suggested that a more accurate formulation would be “Ascendancy Nationalist” or “Anglo-Irish Nationalist” (the essays return again and again to the theme of nationalism as a positive force). He was also, as a writer and as a citizen, quintessentially European. In an elegantly Butlerian introduction to In the Land of Nod, the fourth, posthumous, Lilliput volume, Neal Ascherson writes:

Hubert Butler was what in Central Europe they call a feuilleton writer. The word has misleading echoes of leafy lightness and even weightlessness. But for a century and a half it has meant a special kind of intellectual journalism, witty and often angry, elegant but piercing, and revealing great learning lightly borne, interested in the “epiphanies” which make currents of social and political change visible through the lens of some small accident or absurdity.

The breadth of Butler’s interests and concerns is remarkable, even for a writer whose career spanned the greater part of this tumultuous century. So, as late as 1984, he is writing in fond detail about his house at Maidenhall and the “many beautiful little towns along the Nore,” while from forty years before is preserved a frank, racy, and startlingly evocative account of his time as a not very successful language teacher in Leningrad. “In the end,” he wrote, “I came to the conclusion that almost all those whom I was able to see constantly had obtained the consent of the GPU and were under obligation to report my movements.” Of the agent assigned to keep a “conscientious record of my unmemorable sayings and doings,” Butler writes:

He was, in fact, the ideal spy. It was a disinterested pleasure to him to gossip, and it was a bonus for him to feel patriotic. He never did us any harm. Indeed, hovering on the edge of our little group, he was a kind of insurance that we should not be molested. He liked his lessons and wished us well. He once publicly refuted a rival teacher’s allegation that I had “a terrible Irish accent.”

Butler’s travels take him from the Kilkenny of his childhood to China in the 1950s, from his years working on the literary magazine The Bell in Dublin in the 1940s to the right-to-life debates of 1980s America. Yet, as he declares in his introduction to Escape from the Anthill, reprinted here, “even when these essays appear to be about Russia or Greece or Spain or Yugoslavia, they are really about Ireland…. This focus for me has never varied.” Indeed, he states elsewhere, his focus is narrower still: “I have always believed that local history is more important than national history.”

This last is one of many variations on an abiding theme: the fatuousness of our modern-day concern for the universal at the expense of the particular:

Science has enormously extended the sphere of our responsibilities, while our consciences have remained the same size. Parochially minded people neglect their parishes to pronounce ignorantly about the universe, while the universalists are so conscious of the worldwide struggles of opposing philosophies that the rights and wrongs of any regional conflict dwindle to insignificance against a cosmic panorama. They feel that truth is in some way relative to orientation, and falsehood no more than a wrong adjustment, so that they can never say unequivocally, “That is a lie!” Like the needle of a compass at the North Pole, their moral judgment spins round and round, overwhelming them with information and telling them nothing at all.

However, he is conscious too of the dangers of blinkered parochialism. Perhaps the finest essay in this collection is “The Invader Wore Slippers,” written in 1950, when the tone of wartime propaganda still pervaded public life. Butler recalls how, during the war, “we in Ireland heard much of the jackboot and how we should be trampled beneath it if Britain’s protection failed us,” and how “our imagination, fed on the daily press, showed us a Technicolor picture of barbarity and heroism.”

Advertisement

We did not ask ourselves: “Supposing the invader wears not jackboots, but carpet slippers, or patent-leather pumps, how will I behave, and the respectable X’s, the patriotic Y’s and the pious Z’s?” How could we? The newspapers told us only about the jackboots.

He then goes on to examine the reaction of the native populations of the Channel Islands, of Brittany and Croatia, when the delicately shod Nazi invaders came strolling in. He is particularly scathing about the way in which the Channel Islanders accepted German occupation and settled back to their comfortable lives as before.

The readers of the Guernsey Evening Post were shocked and repelled no doubt to see articles by Goebbels and Lord Haw-Haw, but not to the pitch of stopping their subscriptions. How else could they advertise their cocker spaniels and their lawn mowers or learn about the cricket results?

Although he does not say so directly, it is obvious that Butler harbored very grave doubts about how Ireland would have behaved if there had been an invasion. Elsewhere he quotes a telling declaration made in the Irish parliament in 1943 by Oliver J. Flanagan, who as a member of Fine Gael, the second-largest party in the country, was to be a self-appointed guardian of Irish faith and morals into the 1980s:

“There is one thing,” he said, “that the Germans did and that was to rout the Jews out of their country.” He added that we should rout them out of Ireland: “They crucified our Saviour 1,900 years ago and they have been crucifying us every day of the week.” No one contradicted him.*

In the essay “The Artukovitch File,” Butler follows the postwar trail of the Minister of the Interior in Ante Pavelitch’s unspeakably brutal regime in Croatia under the Nazis. After the fall of Pavelitch, Andrija Artukovitch escaped via Austria and Switzerland, eventually settling in California. On the way to America he had lived for a year in Ireland under an alias. US visas for him and his family were procured through the Irish government, who provided him with false papers. Butler’s outrage at this enormity on the part of his own countrymen is expressed with his usual understated elegance (“The process by which a great persecutor is turned into a martyr is surely an interesting one that needs the closest investigation”), but we are left in no doubt about his contempt for the “patriotic Y’s and the pious Z’s” who would connive at the escape from justice of a man who had taken an active part in some of the most terrible deeds of the war.

Butler acknowledges the centrality to our time of the Nazi death camps—Auschwitz, he declares, is the greatest single crime in human history—but he is determined that even such heinousness will not overshadow the many other atrocities this century has witnessed. He was one of the first in the West to draw attention to the campaign of forced conversion to Roman Catholicism of 2.5 million Orthodox Serbs under the reign of Pavelitch. The campaign resulted in the slaughter of untold tens of thousands of Orthodox Serbs. He quotes from a memorandum from exiled Serbs to the United Nations in 1950:

It is stated that a Franciscan had been commandant of Jasenovac, the worst and biggest of the concentration camps for Serbs and Jews (he had personally taken part in murdering the prisoners…). The memorandum relates how the focal centre for the forced conversions and the massacres had been the Franciscan monastery of Shiroki Brieg in Herzegovina (Artukovitch had been educated there), and how in 1942 a young man who was a law student at the college and a member of the Crusaders, a catholic organization, had won a prize in a competition for the slaughter of the Orthodox by cutting the throats of 1,360 Serbs with a special knife. The prize had been a gold watch, a silver service, a roast suckling pig and some wine.

When, after the war, Butler sought to bring these frightful crimes to public attention, he found himself ostracized in his own country. The Catholic Church had refused to acknowledge that the conversions of the Orthodox Serbs had been forced or had involved violence. At a public meeting in Dublin Butler attempted to read a paper on the issue, but after a few sentences the Papal Nuncio walked out, whereupon the meeting was halted. Next morning the Irish edition of the Sunday Express carried the headline: “Pope’s Envoy Walks Out. Government to Discuss Insult to Nuncio.”

All the local government bodies of the city and county held special meetings to condemn the “Insult.” There were speeches from mayors, ex-mayors, aldermen, creamery managers. The county council expelled me from one of its subcommittees, and I was obliged to resign from another committee. Although my friends put up a fight, I was forced to give up the honorary secretaryship of the Kilkenny Archaeological Society, which I had myself revived and guided through seven difficult years.

It was, in that place, in those times, a familiar story.

The account of this “scandal” makes for lively if dispiriting reading. Butler is one of those rare figures whose mild tone masks their steely resolve. Rarely does he raise his voice—he does not need to, so incisive are his perceptions and so corrosive is his wit. When he does so he falters. Like many humanists, he displays an implacable animosity toward science. “The Children of Drancy,” an essay on the deportation of 4,051 Jewish children to Auschwitz in 1942, through the transit camp at Drancy near Paris, opens out into a superb, angry meditation on public indifference to the fate of the Jews during the war, in which Butler excoriates the champions of scientific progress, such as the novelist C.P. Snow, who in the 1960s drew attention to the widening chasm between the “Two Cultures.” Snow was an indifferent novelist and an undistinguished thinker, but in this matter Butler misses the point.

Anti-Semitism, the idea which killed the Children of Drancy, was small and old and had existed for centuries in small pockets all over Europe. If humane ideals had been cultivated as assiduously as technical ones it would long ago have died without issue in some Lithuanian village. But science gave it wings and swept it by aeroplane and wireless and octuple rotary machines all over Europe and lodged it in Paris, the cultural capital.

The fact is, “science” did not destroy the Children of Drancy. Nor did technology, which Butler fails to distinguish from theoretical science. The technical means of transporting the millions of European Jews to the camps were primitive. Even Zyklon B, the gas used in the killing rooms, required no great scientific skill to produce. No: in the camps, as in every murder site, what killed people was people. Butler, quoting François Mauriac, believes that “the eighteenth-century dream of a future enlightened by the discoveries of science died at Drancy,” and probably he is right—but Drancy, and all the other Drancys, was as much the result of the self-deluding social dreams of the Enlightenment as it was of the technological optimism of the past two and a half centuries. Humanism, before it points to the mote in the eye of science, should look to the beam in its own.

Butler’s vision is all of a piece. Whether he is writing about wartime atrocities or local history, the slaughter of the Jews or Celtic hagiography, he speaks with authenticity. In this he is a member of a dying species. A constant theme, a kind of keening lament throughout most of these essays, is the decline of the Anglo-Irish aristocracy, or “Ascendancy,” whose heir he is. He believed, with sorrowful passion, that the Anglo-Irish reneged on their responsibilities after the War of Independence in 1920 by allowing the Catholic lower middle class to take over entirely the running of the country. After all, he points out, the history of Ireland in the past three hundred years shows that it was the Anglo-Irish, Protestant thinkers and men of action who fought hardest for Irish independence.

The Irish with the defeat and flight of their ruling classes became a peasant people ashamed of their native language, which they associated with subjection and poverty. It was the nineteenth-century scholars and writers, mainly men of Anglo-Irish stock, who first gave it dignity and honour.

This is not untrue—but it is not the whole truth. In a fine essay on Wolfe Tone, the Protestant rebel condemned to death after the 1798 Rising, Butler acknowledges that “Tone’s rebellion… was an utter calamity and ushered in one of the worst of Irish centuries.”

The Irish Parliament, corrupt and unrepresentative but at least Irish, was dissolved; the Orange Order, seeing no tyranny but Popish tyranny, swept away the last traces of that Protestant Republicanism of the North on which Tone had based his hopes of a United Ireland. The Catholic Church in Ireland became increasingly segregationist, and it was considered godless for a Catholic Irishman to be educated alongside his Protestant compatriots. The Irish people, whose distinctive character the eighteenth century had taken for granted, lost its language and, after the Famine, many of its traditions. A period of industrial expansion was followed by one of poverty and emigration. Finally, the partition of Ireland in the 1920s set an official seal on all the historical divisions of our country, racial and cultural and religious, which Tone had striven to abolish.

The title of the essay in which this thumbnail sketch of Irish history occurs, “The Common Name of Irishman,” is taken from Tone himself, whose dream it was to mold the Irish into one nation in which Catholic, Protestant, and Dissenter would play their equal parts irrespective of creed. That dream, and the similar dreams of the Protestant scholars and writers who followed Tone, “could not stand up to the Gaelic dream of Patrick Pearse [leader of the 1916 Rising], for it had been sanctified in blood. Now that dream too has faded, though the blood sacrifice still goes on, like the fire that smolders slowly towards the forest when the picnic is over.” How to account for this catastrophic failure of nerve on the part of the Anglo-Irish gentry? Butler believes it was partly due to the “brain drain” caused by the departure for England throughout the nineteenth century and the early decades of the twentieth of the finest Ascendancy minds and spirits. Another reason was partition.

It reduced the Protestants of the South to political helplessness. The majority clutched nostalgically at the shadows of vanished things, at property and privilege and ancient political loyalties. Imperceptibly they became not more Protestant, as [G.B.] Shaw anticipated they would, but less. Sometimes they seemed not to live in Ireland at all but in a little cocoon woven of ancient prejudices.

A glance at the state of the two Irelands today will show the truth of this. One does not have to be an IRA supporter to acknowledge that partition has been a disaster. As Butler says:

Without the Protestant North we have become lopsided. We lack that vigorous and rebellious northern element which in the eighteenth century was responsible for both our nationalism and our republicanism. And without the South the North has become smug….

Would matters have been otherwise had the Anglo-Irish minority, South and North, kept its nerve, prevailed on its most capable members to stay in Ireland, and seized on a position of responsibility in the new state as Butler believes it was their duty to do? Perhaps. Yet there are many nationalists in Ireland today—not all of them extremists—who would say, who do say, that it was precisely the likes of Butler, the civilized, landed gentry, the descendants of those “nineteenth-century scholars and writers” extolled in these pages, who had to be, if not got rid of, then neutralized, cordoned off behind their yew hedges, in the fastness of their leaf-shadowed drawing rooms, if the “new” Ireland created in the 1920s was to forge its own, native version of itself. The Ireland of de Valera and the Roman Catholic bishops was not graceful, these nationalists would say; it had scant wit, scorned a well-turned sentence, cared nothing for the fate of far-off nations with unpronounceable names; yet the road it has traveled over the past seventy years was its own road, however harsh.

If that is so, then the end of one phase of the journey is now in sight, and perhaps the time is not impossibly far off when, unlikely as it seems now, the Protestant minority will take its rightful place in the life of this island, political and social, and cease looking to a mythologized “England” which cares little for it. Ireland is in sore need of the energies that Shaw’s “violent and arrogant” Protestantism would inject into our national life, should the Anglo-Irish—by which I mean the Southern “Ascendancy,” what is left of it, and the still dauntingly vigorous Northern Unionists—finally release themselves from that “little cocoon woven of ancient prejudices.” The question is, of course, would the majority have the largeness of imagination to welcome them?

It is splendid that a collection of Butler’s essays is now available in the US; but they should also be widely read, as I fear they are not, by Southern Irish politicians, both the professional and the amateur kind. He and some few others like him were, and are, far more substantial than that dream version of them that I, and surely others, used to conjure up among the prize leeks and the genteel accents of the fête Sundays of forty years ago.

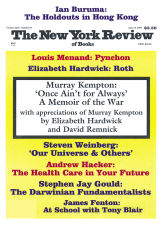

This Issue

June 12, 1997

-

*

The late Oliver J., as he was universally known, would no doubt be bemused and not a little dismayed to find his name appearing in the pages of the dangerously broad-minded New York Review; he once famously declared that before the coming of television “there was no sex in Ireland.” Of course, one does see what he means .

↩