1.

Along Schlobstrasse in the Berlin neighborhood of Steglitz, prosperous shoppers swarm past bright show windows crammed with gleaming appliances, pastel-colored clothing, and fragrant pastries. Though the German economy has sputtered, and sometimes staggered, in recent years, no one here would suspect that. Middle-aged couples, modestly dressed, happily pay prices twice or three times as high as they would be in an American mall—one sees parents casually laying down a hundred dollars a pair for German blue jeans for their teenaged children.

Nothing—not the constant, rapid movement of the traffic, not the flat grey brutality of the modern buildings built here in the Sixties and after, not the mirror-surfaced memorial recently erected to the Jewish residents of Steglitz who died in the Holocaust—interferes with the constant movement of people and goods. This is the Germany built by the Wunderkinder of Germany’s Wirtschaftswunder—the Germany that the writers of the Sixties denounced, that the radicals tried to blow up, and that the rest of Europe and America dumbly envied.

A few blocks away, in the thickly wooded gardens around a local Gymnasium, or high school, it is quiet. In a dark log hut, invisible from the street, a young alumnus of the school takes the leather hood off the head of a falcon. Brilliant eyes burn through the twilit interior as other hunting birds step off their perches to show their fierce faces and utter their characteristic warlike sounds. Outside the hut, geese, ducks, and sheep run and squawk. In the middle of one of Europe’s largest, busiest cities—a city which now has the largest construction site in the world as its center—gentle breezes blow across a tiny farm. It is not the only one: in radical Kreuzberg, several kilometers and even more social classes removed from Steglitz, another city farm welcomes school trips. The children enjoy not only the farm’s animals, but also the totem poles at its corners, erected and consecrated by an American Indian sachem called in by the squatters who created the farm to protect it from the greedy hands of Berlin city planners. Tiny fingers of the German countryside and forest penetrate the wilderness of stone and asphalt.

Berlin yields its secrets slowly. A city of preternaturally ugly buildings, old and new, it bristles with the scars of its violent past. In the old urban center to the east, a vast open space stretches out where the palace of the Hohenzollerns, with its twelve hundred rooms, spectacular sculptured courtyard, and high dome, once dominated the cityscape. The grimy, grey façades of many nearby buildings still show the holes and chips left after the last great battle of World War II and the damage done more recently by pollution. Empty lots and lumpish dark-glass modules of East Bloc Moderne jostle with the colorful fronts and bright signs of recently opened Western businesses. Off to the east stretch the once ornate, now crumbling wedding-cake façades of the “Lockers for Workers” that lined East Berlin’s great boulevard, the Stalin- (later Karl-Marx-) Allee. The eastern city’s vast ceremonial center is the Alexanderplatz—where ill-assorted tall buildings, one of them covered with a wilderness of sheet metal tortured into modernist shapes, surround an enormous central space. Teenagers kicking beer cans, unemployed men drinking, and tourists eating lavish pastries at a Viennese cafe all vanish into insignificance.

In the rich districts to the west, late nineteenth-century villas and apartment buildings line grand streets, their pastel-colored façades swarming with mythological figures, eyes and muscles bulging in warlike fury. Next to them glass and steel skyscrapers admit sunlight through enormous conservatories into offices of gleaming, barren white. In the center of the western city, the Daimler-Benz emblem turns, slowly, on top of the massive mall that once beamed capitalist messages to the captive East; beside it, its base overwhelmed by crowds of scruffy kids, rises the broken spire of the bombed Memorial Church. Between the former east and west zones, in the Potsdamer Platz, once the busiest and later the saddest, emptiest place in Europe, bright pastel water lines, jagged scaffolding, and enormous cranes turn the skyline into an eerie image of destruction and construction, a Jurassic Park of machines that ramp and tear. Not far away from the flying dust and noise of Sony’s rising urban theme park lie the Reichstag and Hitler’s bunker, the “Topography of the Terror,” a cleverly designed set of signs and displays in the empty lot which once housed, and now commemorates, the headquarters of the Gestapo, and Tresor, the one-time vault which now harbors a famous East Berlin club. A little to the north, the ruins of the former Jewish quarter enclose Berlin’s liveliest scene, where the nights in local bars begin long after midnight for German students and Irish construction workers.

Advertisement

Visitors used to Western European order, cleanliness, and beauty often recoil at the first encounter with this city of bloat, wreck, and shadow. If one stays a while, however, Berlin can captivate and charm. The belt of lakes and forests that surrounds the city, its ranks of trees replanted after the war in rows of military straightness, makes Berlin greener than any other great city in Europe. For all the damage done by invaders and architects, some Berlin neighborhoods retain a highly individual appeal. In the western neighborhood of Schöneberg, a center of Berlin’s lively gay culture, and in the Savignyplatz not far away, ornate façades rise over tiny, attractive shops and restaurants. In warm weather, customers swarm about the outside tables with all the northerner’s desperate need for light and air. Squares temporarily become extensions of dwelling places, streets are not passed through, but lived in—just as in the Tuscan piazzas that all cultured West Berliners long for.

Far to the east, in the Rosa-Luxemburg-Platz, the urban scene is equally distinctive, but evokes a radically different—and much more local—set of urban visions. Battered Bauhaus apartment buildings with shops, offices, and places of entertainment on their ground floors, their once-sleek oval balconies leaking stucco on passers-by, call to mind Weimar planners’ dreams of the self-contained machine for living that would make life in Metropolis modern and efficient. Behind the graffiti on some eastern streets in the center one even finds stairwells and courtyards in the old Prussian style, austere and classical, which was mostly buried by the empires of Wilhelm II and Hitler. They quickly catch one’s attention.

So does the city’s odd mix of extreme provincialism and high sophistication. While no newspaper or magazine of high quality is published in Berlin, the city’s museums, operas, and orchestras are superb. It has scholarly and literary book publishers that New York and Boston can only envy. Berlin cabdrivers, many of whom are students, often show a knowledge of Hegel and Nietzsche that would put American professors to shame. (Admittedly, Berlin intellectuals have a propensity to fall for theories once fashionable in Paris or Berkeley, when they arrive, a few years late, at the Zoo Station.) Berlin cuisine is not high: its characteristic dish—pig’s knuckles, eaten with a Teutonic version of polenta and washed down with corn liquor and thin beer—will never threaten the popularity of choucroute garnie. But the city’s language is sharp and powerful. Berliners cherish a peculiar gallows humor, best expressed in the local dialect, with its characteristic substitution of j for the hard g (guten morgen becomes yuten moryen in Berlinerisch) and its Yiddishisms, so chilling to the American who does not expect them. “You can’t eat as much as you would like to throw up”—Max Liebermann’s famous remark about the Nazis marching through the Brandenburg Gate epitomizes a satirical, gallows-humored turn of thought that remained alive even in the spy-haunted wastes of East Berlin (West child to East child: “We have bananas, you don’t.” East child: “So? We have socialism.” West child: “Big deal: we’ll get socialism too.” East child: “Then you won’t have any bananas either”).1

Like Thomas Wolfe’s Brooklyn, Berlin refuses to be known as a whole. Even Walter Benjamin, who traced the paths of memory into lost streets, cafés, and apartments, and expressed his love for his lost city in prose of delicate beauty, could not speak the local dialect—as his friend Gershom Scholem, whose language and temperament were permanently marked by his own Berlin upbringing, noted with amusement. Other European cities describe their pasts in a visual language that lends itself to decoding. In Vienna, as Carl Schorske has shown, the Athenian parliament building and Gothic city hall on the Ring still record the aspirations of nineteenth-century liberals to build the civic institutions which their imperial city had never possessed, and to connect these with a history Vienna had not experienced. The concrete antiaircraft towers built in World War II, never torn down, dominate parts of the skyline, huge mushrooms of grey concrete which make the city’s collective effort to forget its Nazi period even more starkly visible than its failed experiment with liberalism. In Berlin, by contrast, every neighborhood speaks with a slightly different inflection, hard to record or explain. For all the precision of the city maps that enable the newcomer to find addresses in Berlin’s maze of homonymous streets, the profile of the city as a whole remains hard to trace, harder still to decipher.

2.

Historians, naturally, find Berlin’s elusiveness a challenge to their curiosity and industry. A number of them have recently followed different threads to what they see as the secret at the heart of Berlin’s stone labyrinth. Brian Ladd faces the city’s fragmented past and incoherent present head on. In his lucid study The Ghosts of Berlin, he explores the history of the built city, period by period, paying close attention to the numerous recent controversies about the meanings of form and space in the city—controversies which have surrounded everything from such very conspicuous, public projects as the new Jewish Museum designed by Daniel Libeskind, the future of which remains uncertain, to the renaming of obscure East Berlin streets after the fall of the Berlin Wall. His well-written and well-illustrated book amounts to a brief history of the city as well as a guide to its landscape.

Advertisement

Ladd shows particular sensitivity to the aesthetic and planning principles of the former East Germany—principles little appreciated in the West even before the collapse of communism, and now rapidly becoming indecipherable as the society in which they took shape disappears into the past. Tracing the creation of the Stalinallee and Alexanderplatz, for example, he carefully explains how East German planners deliberately placed their emphasis on the city center and tried to produce an imposing style for it, a showcase for Stalinism’s ability to mobilize men and resources (Ladd describes their chosen style as “an amalgam of Schinkel and Stalin”). The Stalinallee, with its falling Meissen façade tiles and kitsch excesses of scale, looks foolish now, an emblem of forlorn hopes for a future lost to tyranny and corruption. But in its period, the “first socialist boulevard,” symbolically running west to east and inhabited, to a great extent, by workers and war victims rather than apparatchiks, can be seen both as a high point of modernism and an ambitious attempt to muster civic energies.

Early Western observers praised the street as grander than anything in West Berlin; “the chameleon architect of high capitalism,” Philip Johnson, agreed with this when visiting Berlin as late as 1993. Ladd carefully and convincingly explains why the now desolate and rundown East German “satellite cities” on the edge of Berlin, like Marzahn, made social and economic, as well as aesthetic, sense as part of the all-embracing, cradle-to-the-grave system they served. Much East German public space—like the Alexanderplatz, a vast square laid out to house great, staged demonstrations and later reconfigured to buy popular loyalty with a range of consumer goods not to be found elsewhere in the East—now appears to be urban wasteland, broken and incoherent. Ladd does not suffer from what the Germans now call Ostalgie, nostalgia for the DDR, but he shows that its planners tried to achieve serious aesthetic and social goals—if with incongruous and loathsome methods that left their society and their ecology riddled with pollution of many kinds.2

Above all, Ladd makes clear just why the public planning of Berlin has become a battlefield. Intellectuals of the graying but still articulate Berlin left, who turned out in some numbers on the first weekend in June this year to commemorate the death of Benno Ohnesorg, the Berlin student killed thirty years ago during demonstrations against the Shah of Iran, remain determined that practically every horror of the Nazi past have some visible monument. But they now confront equally articulate intellectuals of the newly vigorous right, determined to feel and show pride in their German identity and convinced that enough, and more than enough, has been said and done to make good any crimes that Germans may have committed under Hitler. At the same time, the faceless barons of international business, who, like angels, have no memories, scramble to grab, mark, and rebuild prominent central sites, turning rubble laden with memories into pastel playgrounds for tourists as divorced from time and history as Disney’s new Times Square.

Huge monuments disappear in weeks—as the Berlin Wall, once visible from outer space, vanished after 1989, leaving bicycle paths where barbed wire and armed guards had lain in wait for those trying to desert. Some of the most striking signs of Berlin’s past—Hitler’s bunker, for example—seem headed for oblivion, since no one can imagine how to preserve them and make them accessible without celebrating the unspeakable. Others—like Schinkel’s splendid classical guard house, the Neue Wache, and the still-unbuilt Holocaust Memorial—have become political litmus tests. Every effort to commission a monument calls forth storms of those long, anguished position statements which German intellectuals love to compose, and German newspapers to publish.

Yet other once-legible signs of past aesthetic and political programs—like the characteristic Nazi building complexes at Tempelhof Airport, Fehrbellinerplatz, and elsewhere, with their squared shapes, long colonnades, and impressive doors—have simply become a normal part of the city. During the 1980s Germany’s historians were locked in ferocious combat over the responsibility for the destruction of the Jews. During the Nineties they were torn by anguished conflict over the future shape of their capital—a conflict which flames up as more and more insist on Germans’ right to oblivion for the sins, and pride for the achievements, of the past. Meanwhile the shoppers have begun to stream east, into the well-lit, expensive shops of the Friedrichstrasse Passagen. Soon Steglitz will come to Potsdamer Platz. 3

3.

Ladd looks backward from the present; Peter Fritzsche, by contrast, plunges directly into the Berlin of 1900 to 1920. This new Babylon, a seemingly endless sprawl of factories and tenements, overwhelmed the lucid neoclassical Berlin of the early nineteenth century, the city of Karl Friedrich Schinkel, who had in his turn transformed the walled garrison city of the old Prussian aristocracy. Fritzsche seeks to decode the mysteries of the “Chicago by the Spree” that replaced Schinkel’s Prussian Athens. He takes his cue from the city’s most passionate and expert observers—the journalists who chronicled its growth in the feuilletons and news articles of the papers that all Berliners read on buses and in cafés. Like Franz Hessel—one of the most evocative and eloquent of these writers—Fritzsche sees Berlin as a dynamic hieroglyph, a powerful if mostly forgotten character in the visual language of Futurism.

A center of Germany’s first industrial revolution, Berlin harbored important factories, where Siemens and many others pioneered the modern world of work strictly defined by time clocks. But the whole city, not just its industrial work force, became a perpetual motion machine in the years around 1900. Buses and street railways hurled Berlin’s millions of inhabitants from home to work on weekdays and took them on weekends from the city’s dirty core to its magnificent beaches at Wannsee and its spectacularly landscaped complex of palaces at Potsdam. Developers pushed the city’s population into massive five-story housing complexes, organized around courtyards. They turned country into city, moving the border of the suburbs ever farther out, until the city swallowed them.

They moved people too. Every first of April and first of October, crowds carried their possessions through the streets as the Trockenmieter—the poor families who lived at reduced rents in new apartments whose plaster was still wet—changed to still newer “rent barracks” distinguishable from the old ones only because they were cheaper. Producers sent teams of dancers onto the stages of cabarets, their identical, high-kicking legs providing a human counterpart to the machines in factories—“A button is pressed,” wrote Siegfried Kracauer, “and the girl contraption cranks into motion, performing impressively at thirty-two horsepower.”4

Nothing, however, moved more quickly and regularly in Berlin than the word—especially the words that described the city itself. New editions of some papers appeared hourly. Columns at the corners of streets announced the arrival of circuses, the changes of program at theaters, and new acts at music halls in layer upon layer of vivid posters. The city and its interpreters deluged its inhabitants with sights and sounds and accounts of both. Berlin became the model of the modern urban experience—the experience without a larger narrative behind it, the unending flow of impressions that philosophers and feuilletonists struggled to evoke:

Hammers roar, machines rumble, the wagons of butchers and the carts of bakers roll past the house before daybreak. Countless bells wail uninterruptedly. Thousands of doors are slammed shut. Thousands of hungry people haggle and scream, they scream and argue beside our very ears and fill the streets of the city with their business and their trade. The telephone rings. The automobile horn honks. The streetcar screeches. A train rolls over the iron bridge. Straight through my aching head, straight through our finest thoughts.

History—so Delmore Schwartz remarked, as he lay awake through yet another intolerably busy, pounding New York night—was a nightmare during which he was trying to get a good night’s rest. He would have recognized the intellectuals of early twentieth-century Berlin as fellow sufferers writhing in modernity’s noose of noise. Like Schwartz, Fritzsche argues, the writers and readers of imperial and Weimar Berlin found themselves cocooned in signs that became more and more indecipherable. The ever-changing images of commodities and performances projected onto the screen of their consciousness merged into a single illegible stream. The writers most in sympathy with Berlin’s peculiar music—like Franz Hessel and Alfred Döblin—plunged into it like swimmers. They described the city’s indistinct mass, its endless, boring streets and dull suburbs, the life of its courts and back rooms, taking a ceaseless delight in prosaic detail, but not taking a position—critical or celebratory, historical or aesthetic—about the meaning or direction of the city’s endless motion.

Fritzsche, the coauthor of an excellent walking guide to Berlin, knows the physical city very well. He does a nice job of reconstructing the city of words that Ullstein and other publishers reared in the newspaper district on the Kochstrasse. At the same time, though, he exaggerates the passivity of observers before the unrolling noisy movie of city life. When Joseph Roth brought his all-seeing outsider’s eye to the poor, crowded streets of the Jewish quarter, he recorded their poverty with the hallucinatory vividness of a newsreel cameraman and the polemical verve of a fellow exile:

No street in the world is as sad. Hirtenstrasse does not even have the hopeless cheerfulness of more dirt…. There are no streetcars running along it. No buses. Rarely an automobile. Always trucks, the plebeians among vehicles. There are little taverns stuck in walls. Down at the bottom of steps. Narrow, dirty, worn-out steps, like the negatives of worn-down heels. There is rubbish in the hallways. Including rubbish that has been collected, bought. Rubbish as an object of trade. Old newspapers. Torn stockings. Soles of shoes.5

Gabriele Tergit, whose columns appeared between World War I and 1932 in the Berliner Tageblatt and the Weltbühne, used her reportage on Berlin courts and cafés as the basis for a lucid, powerful analysis and criticism—leftist, feminist, Jewish—of her chosen city. In Tergit’s sharp-edged feuilletons, whores and Communists, poor women and suspicious neighbors spoke in all their smudged humanity. She even accorded the Nazis their own strained voices. Only the Prussian officials who could not understand the suffering of the city’s poor women and children and the dangers posed by its right-wing radicals lay entirely outside the capacious borders of her sympathies. Writers like these traced the jagged, horrifying logic of the city’s social, political, and cultural collapse in the late 1920s and early 1930s as vividly as Christopher Isherwood did in his Berlin stories. They managed this feat while working at frantic Berlin speed, day by day, to provide copy for the newspapers, whose editors were often more interested in the length than the quality of the prose they received.6

Berlin artists also surveyed—and survey—the history of the city. Jules Laforgue, who spent the years 1881 to 1886, almost a quarter of his short life, in Berlin as French reader to Empress Augusta, found little to praise and much to ridicule as he observed the Berlin scene from the window of his bedroom in a palace on Unter den Linden, entering his observations in a journal which has just been nicely translated into English. Like many other foreigners, he mocked the enormous feet of the Berlin women (“The size of a woman’s foot is not a myth”) and the terrifyingly inedible food of the Berlin restaurants (“As soon as it gets warm, the waiter will recommend to you, instead of a potage, cold soup or ‘beer soup.’ Answer, ‘No, no, never!”‘). Berlin manners, with their combination of crudity and formality, filled him with fascinated horror: “I remember how astonished I was to hear a lady greeting a friend by saying, ‘How are you, Geheimräthchen?”‘; “A waiter speaking to another waiter: ‘Come here, Herr Colleague.”‘ The Berliners’ ignorance of Impressionist painting merely confirmed his low opinion of their general culture.

4.

Laforgue approved whole-heartedly of one Berliner—the painter Adolph Menzel, “no taller than a cuirassier-guard’s boot, bedecked with pendants and orders, but also wearing the Legion of Honor, coming and going, knowing everyone, not missing a single one of these parties, moving among all these personages like a gnome.” Menzel—recently the subject of a splendid, little-publicized exhibit at the National Gallery in Washington—devoted much of his lengthy and successful career to creating a visual encyclopedia of nineteenth-century Berlin. For all his interest in the new art of photography, Menzel remained committed to paint, in which he could attain effects no camera could match, ranging from hallucinatory realism to bold, sketchy evocations of the city’s thousand moods. He applied his extraordinary technique to buildings and society alike. Though he knew the glittering squares and boulevards of Haussmann’s Paris—which he collected into a splendid pastiche of Parisian street life—he devoted loving attention to the dusty back yards, bare fire walls, and uniform façades of the new Berlin tenements—and to the building workers who reared them and the scaffolds on which they worked. When painting a court ball he not only rendered the brilliance of uniforms and decorations, ornate walls and bare female shoulders, with a deftness that excited Manet so much he copied the work, but also revealed a Tolstoyan gift for the analysis and description of character.

Yet Menzel did not accept the military and imperialist values of the imperial court, as his minutely detailed drawings of the dead of the Prussian wars of 1866 and 1870 clearly show. Like the best of the feuilletonists, Menzel followed the dizzying growth of Berlin from Prussian garrison town to imperial capital without ever losing his tough-minded, independent point of view—the same point of view that led him to rendering the rats he saw in the Berlin sewers as well as the animals he saw in the world-famous Berlin zoo, and to portraying the latter from the point of view not of its visitors but of its caged animals.

Menzel preserves a Berlin most foreigners do not know. George Grosz, by contrast, created a Berlin familiar to educated people throughout the West—though the images with which he is identified are anything but a simple and accurate representation of a historical city. As Frank Whitford shows in The Berlin of George Grosz, the catalog of an exhibition now at the Royal Academy in London, Grosz explored Berlin over a long period. Like Menzel, he followed the city in motion, living through and interpreting its passage from capital of the Wilhelmine empire to capital of the Nazi state. As a young art student living at the suburban edge of the city, Grosz worked with pencil, pen, and watercolors to express the melancholy quiet of dark streets and blank-walled apartment houses. As a middle-aged man anxious to support a family, he returned to watercolors to sketch the fashionable mothers and nannies of the west end of Berlin, strolling elegant streets and peering in the windows of expensive shops. Like so many painters of modern life from Manet and Degas onward, he loved and recorded cafés, circuses, and cabarets, vast beer halls and six-day bicycle races.

But the Grosz whose images have fixed themselves firmly in the historical imagination of the West—so firmly that they are regularly used, as Beth Irwin Lewis has pointed out,7 to give the thrill of authenticity to articles on any aspect of Weimar—was not a patient, attentive watercolorist. A radical and a dandy, conspicuous for his elegant clothes, powdered face, and skull-topped cane, Grosz fascinated the young artists and writers of his generation in part through a gift for performance art which made him stand out even in what he liked to call the Café Grössenwahn (Café Megalomania)—the Café des Westens, where he and other creatures of the artistic night congregated: “One night in 1915,” Erwin Blumenfeld recalled, “I went, slightly merry, to the urinal on Potsdamer Platz. A young dandy entered from the opposite side, put his monocle in his eye, opened his black and white checked trousers and traced my profile in one fell swoop on the wall in so masterly a fashion that I could not help exclaiming in admiration. We became friends.”

It was no accident that Grosz created this brilliant effect on the side of a urinal. A meticulously trained artist who saw himself as the successor of Breughel and Hogarth, Grosz learned from Expressionists like Meidner, Futurists like Boccioni, and even the “metaphysical painter” De Chirico. But he needed a special visual idiom to convey both what he saw from very early in life as the irremediable ugliness of his fellow Germans and what he came to see, returning to Berlin after his brief military service, as the cold, gray capital city, the center of greed and violence.

Grosz—so he recalled in 1923—“studied the most direct utterances of the artistic instinct. I copied the folk drawings in urinals, because they seemed to me to convey strong feelings with the greatest economy and immediacy.” By doing so he developed what he described as a “blade-sharp” drawing style. He practiced this constantly, in the best fashion of the classical artist, sketching everything he saw on the street. Soon the art of the latrine became the only proper medium for depicting a society which Grosz saw as nothing more than a steaming heap of entrails and offal.

Grosz left unforgettable images of war, revolution, and inflation in the minds of his contemporaries—as well as our collective memory. Increasingly committed and combative, he attacked the militarism of the war years as a species of collective madness. The pulsing energies of the city spilled out into visions of riot and massacre. Death walked among the hard-faced, moustached soldiers, bearded Jews, elegant women, and crippled beggars of the Friedrichstrasse. Streets and cafés threatened more than they promised: windows opened on scenes of sex and murder. Gradually, the enemies of mankind took on a fixed, if generalized, identity: politicians with shit for brains steaming in little chamber pots; soldiers, pastors, and Philistine bourgeois, sometimes clutching their copies of Goethe; women, naked or seductively half-dressed, lying in their own blood or clinging to the oppressors of humanity. The poor, too, took on a collective face: a mask of misery, shown in profile, which Grosz insisted—in what became deliberate contravention of Communist aesthetic principles—was the natural result of centuries of oppression.

Only a visual language as unequivocal and accessible as this—so Grosz argued, in incendiary manifestos and public acts of outrage against the high art tradition—could make works of art into acts of opposition, clarifying images which would show the ordinary man who his enemies were. With the help of friends like Wieland Herzfelde, whose company, Malik Verlag, braved financial difficulties and risked censorship to publish Grosz’s graphic work, Grosz set himself to expose Ebert and Noske. These politicians, who called themselves Social Democrats, had supposedly erected a constitutional government. In fact, Grosz believed, they had crushed Germany’s one chance for real change, the revolutionary movement that began in 1918—the one time, so Kurt Tucholsky recalled, when Prussia’s frozen earth cracked and moved. The willing followers of reaction, they had caused the deaths of the Spartacists Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht. Later Grosz would turn the sharp edge of his pen against the new society that formed in the Berlin of the inflation years, the German Veneerings who frequented the city’s varied range of bars and brothels. Later still he would attack the Nazis—whose threat he understood earlier and better than most of Weimar’s other intellectuals.

Grosz’s caricatures struck home, but the political education he offered seldom inspired political action. Young intellectuals took his savage cynicism as a license to avoid constructive engagement with the Weimar Republic. “We young students,” Hannah Arendt recalled, “did not read the newspapers in those years. George Grosz’s cartoons seemed to us not satires but realistic reportage: we knew those types; they were all around us. Should we mount the barricades for that?”8 Viewed with the cold comfort of hindsight, Grosz’s images inspire other emotions as well. Grosz shared traits with the Nazis he detested and fought. Like them, he despised the Republic, with its constitutional guarantees and elective government, as much as its enemies. Like them, he dehumanized his opponents, using physical ugliness, rather than arguments, to make his political points. More recently, the role of women in Grosz’s work has provoked criticism. Why did this enemy of the bourgeois order, this hater of reaction, so often portray woman as coarse, mutilated, bleeding corpses?9

Scholars who admire Grosz’s artistic gifts and hatred of oppression insist, rightly, that he included himself in his condemnation of humanity—as when he posed for a famous photograph as Jack the Ripper, threatening his own wife as she preened in a bathing suit before a mirror. They also point to the irony that pervaded his work, to his continual awareness that he was always acting, always posing. Most recently of all, close study of Grosz’s erotic images and their sources—which included a large personal collection of sexy postcards—has revealed that he could satirize male impotence as effectively as female lust.

Yet such arguments, though partly convincing, cannot eradicate the bad taste that Grosz—like Brecht—often leaves. And this bad taste infects the imaginary Berlin that he called to life. The city Grosz lived in, after all, was not only an urban nightmare but also a place of liberation, unique in Europe, to many of the independent young women who worked and voted there—as well as to the Berlin homosexuals whose institutions and subcultures, so vividly memorialized by Isherwood, await their George Chauncey. Women’s new freedom, Beth Irwin Lewis has argued, affected Grosz and some of his colleagues as strongly as militarism and repression. But what Grosz experienced as the City of Dreadful Night others saw as an image of urban modernism at its high meridian of freedom, an open society in which any life could be lived, any idea discussed, any text or image offered to the public—usually at three in the morning, in bars and cafés whose lights served less to expose the ugliness of a degenerate society than to hold off, for a time, the darkness that waited outside.

5.

Both Menzel and Grosz left one feature of the Berlin they wandered through unrecorded. The city spoke to its visitors not only through its newspapers and “Littfäbsäulen,” the pillars on street corners, but also with the façades of its buildings. The characteristic Berlin shop of the nineteenth century, as Laforgue and many others observed, was not the modern store then taking shape in Paris and elsewhere: an establishment at street level, with large show windows. Many Berlin shops were dark little holes, below ground level, reached by short stairways leading down from the street. Their signs took the form of painted inscriptions on the walls, which identified them as bakeries or dairies, specialists in doves or outlets for “colonial wares,” and named their owners. The destruction and rebuilding of West Berlin replaced this outmoded dialect of retail sales with the new American visual language of neon and glaring colors.

But in some of the eastern parts of the city—especially in the workers’ district of Prenzlauer Berg, where mile upon mile of tenements escaped Allied bombs and Russian tanks, only to deteriorate slowly under an eastern regime more interested in building flimsy new towns than in repairing old ones—the signs survive, the epigraphic record of a society as dead as that of ancient Aphrodisias. A submerged world of small shops and fragile businesses flickers back into life as one walks these streets—though it is rapidly disappearing as Western settlers and chain stores move into this largely intact turn-of-the-century neighborhood, where elegant new signs advertising computer software and design studios are redrawing the language of the street.

In the old Jewish quarter, the Scheunenviertel, fewer of the old signs remain. The battle for the city in 1945 severely damaged its streets, which were already poor. After the war, many ruins made way for the plain concrete slabs of East German prefabricated housing, while others simply disintegrated. Nothing conveys better the distance between the lost city and the modern one than the installations carried out in the Scheunenviertel early in the 1990s by an Israeli-American artist, Shimon Attie. He assembled photographs of the inhabitants and shopfronts, reading rooms and movie houses, of the old Jewish quarter. These he projected, at night, on ruined old construction and ruinous modern prefabs alike (see photograph on page 49.) Attie’s installations, which provoked much irritation from the inhabitants of the buildings he used, were temporary art, by necessity. But luminous photographs preserve his projections and their modern surroundings: the black and white of a lost history projected over the shop windows and graffiti of the present.

Turning the pages of Attie’s The Writing on the Walls, readers can glimpse the old men and young children, scholarly publishers and popular amusements, of a lost Jewish Berlin. They can spell out the Hebrew and Yiddish words on long-smashed shopfronts, peer through long-broken windows at the bathhouses and reading rooms that once sustained a lively Jewish culture. No one—no historian, no writer—has separated the layers of Berlin’s past with a more delicate hand. And no one has shown more vividly just how impossible it is to descend to the great sunken vessels of Prussian, imperial, and Weimar Berlin—much less to raise any of them to the modern surface. The walls speak in a murmur just too low and strange to follow; we cannot map the broken labyrinths, fragments of which the artist has collected and displayed.

Like Jerusalem or Rome, Berlin is a haunted city, its past omnipresent both as ruin and as kitschy reconstruction, its landscape a palimpsest which bores the inattentive but seduces the curious. The city’s gallows humor and ironic humanity have survived inflation and bombing, Hitler and Ulbricht. But they must now resist the incompetence and corruption of the local politicians as well as survive the thousands of bureaucrats who will move from Bonn when Berlin becomes the capital of Germany, and overcome the cruel deadness of the examples of International Glitz rising in the Potsdamer Platz. It remains to be seen if politicians and developers can eradicate what time and history, warfare and city planning, ideology and market have created. 10

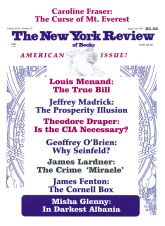

This Issue

August 14, 1997

-

1

Clément de Wroblewsky, “Die Hauptstadt Berlin. Ein Witz,” in Berlin—Hauptstadt der DDR 1949-1989. Utopie und Realität, edited by Bernd Wilczek (Baden-Baden: Elster Verlag, 1995), pp. 247-264.

↩ -

2

See also the powerful essays in Wilczek, Berlin—Hauptstadt der DDR, which offer a variety of German viewpoints.

↩ -

3

Berlin’s recent struggles over memory and history have been the object of several extraordinary recent books by Americans that lie outside the normal forms of historical and art-historical work discussed here. See Susan Neiman’s memoir of intellectual life in the last five years of West Berlin’s isolation, Slow Fire: Jewish Notes from Berlin (Schocken, 1992); J.S. Marcus’s novel on Berlin just after the Wende, The Captain’s Fire (Knopf, 1996); and Jane Kramer’s reportage, The Politics of Memory (Random House, 1996).

↩ -

4

The Weimar Republic Sourcebook, edited by Anton Kaes, Martin Jay, and Edward Dimendberg (University of California Press, 1994), p. 565. Peter Jelavich has dismantled many legends about the politics of popular entertainments in his fine history, Berlin Cabaret (Harvard University Press, 1993).

↩ -

5

The Weimar Republic Sourcebook, Kaes et al., p. 265, slightly altered; for the original see Joseph Roth, Juden auf Wanderschaft (Köln: Kiepenheuer & Witsch, 1985), p. 49.

↩ -

6

See Gabriele Tergit [Elise Reifenburg], Atem einer anderen Welt: Berliner Reportagen, edited by J. Brüning (Suhrkamp, 1994), as well as her novel, Käsebier erobert den Kurfürstendamm (Berlin: Arani, 1988); two samples of her journalism appear in Kaes et al., The Weimar Republic Sourcebook, pp. 202-203, 632-633.

↩ -

7

Beth Irwin Lewis, Georg Grosz: Art and Politics in the Weimar Republic, second edition (Princeton University Press, 1991).

↩ -

8

Lewis, Georg Grosz, p. 8.

↩ -

9

See, in addition to Lewis’s classic monograph, her more recent article “‘Lustmord’: Inside the Windows of the Metropolis” in Berlin: Culture and Metropolis, edited by Charles W. Haxthausen and Heidrun Suhr (University of Minnesota Press, 1990), pp. 111- 140; Maria Tatar, Lustmord: Sexual Murder in Weimar Germany (Princeton University Press, 1995); and Barbara McCloskey, George Grosz and the Communist Party: Art and Radicalism in Crisis, 1918 to 1936 (Princeton University Press, 1997).

↩ -

10

Two more books deserve mention. Alan Balfour’s Berlin: The Politics of Order, 1737-1989 (Rizzoli, 1990) traces the development of Leipziger Platz and Potsdamer Platz, and through them of the city as a whole, in a very original way. Ronald Taylor’s Berlin and its Culture: A Historical Portrait (Yale University Press, 1997) offers a fast-moving, informative survey of Berlin’s art, architecture, films, music, and literature, also ending in 1989.

↩