A few months ago, a terra-cotta bust of a woman passed through the London auction rooms, leaving a little puzzlement and worry in its wake. Once, in its glory days, as a work of Andrea del Verrocchio, it had graced the collection of J. Pierpont Morgan. That interesting scholar W.R. Valentiner, who earlier this century was lured from Berlin to the Metropolitan Museum in New York (his career forms a link between Bode’s Berlin and the Getty Museum in Malibu), compared the profile of the bust with a drawing by Leonardo in Windsor Castle. He thought that the master (Verrocchio) and his most famous pupil (Leonardo) might have used the same model.1 But other voices were raised to denounce the work as a fake. Or, if not a fake, as a portrait of a nineteenth-century sitter in Renaissance costume. This low opinion prevailed over Valentiner’s, and the bust was disgraced, deaccessioned, without chance of reprieve.

But that was not the end of the story, for the auction room catalog announced that the bust had recently been subjected to a thermoluminescence test, which proved that it had last been fired in or around the fifteenth century. Whatever it was, there was no reason to call it a fake. And if it was not a fake, perhaps Valentiner’s opinion might merit further consideration. For, when it came to Verrocchio scholarship, Valentiner was not nobody. In 1933 he was able to show that a candelabrum in the Schlossmuseum in Berlin was a documented work of Verrocchio. This is now one of the treasures of the Rijksmuseum.2

There are not many known surviving works by Verrocchio. Andrew Butterfield’s new book lists thirty, of which four are uncertain and others seem more the work of the studio than of the master. That makes Verrocchio as rare as Vermeer, but with this exciting difference: Verrocchios—real ones—have turned up, both through inspired acts of reattribution and as objects previously unknown to scholarship. What is more, it is quite certain that there are others waiting to be found. In the 1980s, a terra-cotta modello for the figure of the executioner of John the Baptist turned up on the London antiques market. But other sketch models for the same relief scene were once known. If the heirs of Baron Adolphe Rothschild would just investigate their cupboards a little more carefully, they might yet find them.

One might think that with so many art historians crawling over every inch of its surface there would be nothing left to discover in Florence. But Butterfield, if he is right, has found a Verrocchio in the Bargello itself. And meanwhile a curator of that museum, Beatrice Paolozzi Strozzi, has made a particularly fascinating discovery. Taking a second look at an unprepossessing crucifix, which had already been logged as nothing in particular, she decided to have it cleaned. What emerged from beneath centuries of filth was the original polychromy of a Verrocchio Christ. This discovery was published in 1994.3

If an item such as a crucifix has spent all its life in a church, and has been considered as a liturgical object rather than a work of art, the chances are that it will have built up a surface consisting of alternate layers of candle soot and repaint. Nobody ever thought of stripping it, only of touching it up. But if a dealer, a collector, or (in some cases worst of all) a museum has been involved, then the likelihood is that at some point in its career the object will have been stripped of what was considered inauthentic polychromy. A terra cotta will have been soaked in solvent, scrubbed with steel wool, “taken back” to a “pure” original state. And if this state was found to be aesthetically unsatisfactory (supposing the object turned out to be incomplete or cracked or broken), then the restorer will have made up the deficiencies and covered his work with a layer of a substance much resembling an item which used to appear on British menus—Brown Windsor Soup. This soupy, lustrous, gravy finish was at the height of its popularity around the turn of the century, in the heyday of J. Pierpont Morgan’s collecting.

In the fifteenth century, a terra-cotta bust—say, a portrait produced for a domestic setting—would, after firing, have had any kiln cracks or other deficiencies made good. It would then have been coated with a thin layer of gesso before being painted, and perhaps partially gilded. Even marble sculptures were sometimes painted and gilded, and there is a beautiful surviving example of this technique in the recently opened gallery that the Metropolitan Museum has devoted to the sculpture of this period. The world of the Florentine plastic arts was not entirely composed of monochrome effects in marble, terra cotta, and bronze. Sculptures were glazed and fired. They were painted and gilded. They were produced by means which other ages would have abhorred—portrait busts being made from death masks, for instance—and in such “unclassical” materials as papier-mâché or wax or plaster. There were works in mixed media. Verrocchio’s crucifix is one such: parts of it are built up with pieces of cork; the loincloth or perizonium is made of fabric dipped in plaster. An object of this kind, placed in a damp cellar, will soon disintegrate. A flood would be fatal to it. That is one reason why so little of this kind of work has survived. But another reason is that the history of taste turned so decisively against it.

Advertisement

The Pierpont Morgan bust was intriguing because it was known that the Brown Windsor surface concealed a fifteenth-century ceramic core. But nobody knew what else it concealed. Were there the remains of some wonderful polychromy, or was it a horrible botch-up? Why had it once been so admired as a Verrocchio, then so detested as a fake? During the days of its display people turned it over and shone torches in its eyes, frowned at it, made notes on its condition, and, after all this attention, bits of brown surface flaked off—as if the curious had picked at the scab. One felt sorry for it, in this protracted humiliation. And then it sold…but for a modest sum. One way or another it had failed to convince.

But who knows what it will look like on its next public appearance? Who knows what the next episode of its critical fortune will be?

2.

Verrocchio’s own critical fortune had to endure two and a half centuries of silence, during which we have to assume that a great deal of his work either disintegrated or was deliberately destroyed. It was only in the nineteenth century that he returned to the prominent position he had once occupied. Born in the 1430s, he died in 1488, the greatest sculptor in the Florentine tradition between Donatello and Michelangelo. And to be one of the greatest artists in that tradition, in the eyes of the nineteenth century, was like being one of the greatest artists in Periclean Athens.

Here is Ruskin in 1853, evoking the early Renaissance:

For the first time since the destruction of Rome, the world had seen, in the work of the greatest artists of the fifteenth century,—in the painting of Ghirlandaio, Masaccio, Francia, Perugino, Pinturrichio, and Bellini; in the sculpture of Mino da Fiesole, of Ghiberti, and Verrocchio,—a perfection of execution and fullness of knowledge which cast all previous art into the shade, and which, being in the work of those men united with all that was great of former days, did indeed justify the utmost enthusiasm with which their efforts were, or could be, regarded.

And Ruskin goes on to say, of what he calls “cinque-cento work”:

When it has been done by a truly great man, whose life and strength could not be oppressed, and who turned to good account the whole science of his day, nothing is more exquisite. I do not believe, for instance, that there is a more glorious work of sculpture existing in the whole world than that equestrian statue of Bartolomeo Colleone, by Verrocchio.4

It was praise like this that sent generations of tourists to the Campo SS. Giovanni e Paolo in Venice to gaze up at the features of Verrocchio’s stern condottiere there. And it was praise like this that inspired dealers, collectors, and museum directors to seek out and acquire such works as they could. Meanwhile it was the job of scholars in the first part of this century to denounce and eliminate the numerous fakes and mistakes that had found their way into the corpus. They wanted a leaner Verrocchio, incapable of inferior work. In a way, such decisions must always have an element of the arbitrary. The connoisseur sets his own standards for what is to be tolerated as an autograph work. He conducts his own calibration. Butterfield sets the standard high, perhaps severely so. But the quality of reasoning, the depth of documentation, and above all the knowledge and sense of cultural context make this monograph quite different from anything else ever written about its subject. This is less of a compliment than it sounds, because the literature on Verrocchio is curiously thin. But to put the matter plainly, this is a book with no rivals.

Verrocchio was born into the artisan class of Florence: his father was a fornaciaio (which means that he worked with a kiln) and a member of the stoneworkers’ guild. Later he became a customs agent. Verrocchio could have received some instruction from him in the working of stone and clay. Vasari, whose high opinion of Verrocchio is tempered by the observation that his manner was “somewhat hard and crude” and the product of infinite study, calls him “a goldsmith, a master of perspective, a sculptor, a wood-carver, a painter, and a musician.” Of his goldsmith’s work he mentions buttons for copes and “particularly a cup, full of animals, foliage, and other bizarre fancies, which is known to all goldsmiths, and casts are taken of it.” He made a copper ball to go on the cupola of the Duomo (it was later destroyed). Butterfield says that “Renaissance artists who trained initially as goldsmiths often later became painters, architects, and bronze sculptors, but almost never achieved distinction in carving marble” and that Verrocchio is one of the few exceptions to this rule. What survives of his sculptural work shows us the full range of activity for an artist of his day—with one exception, that of the free-standing figure or group in stone. In the following cicerone, based on Butterfield’s work and my own recent travels, I have tried (not wholly successfully, as will appear) to consider each object in the new canon, in situ.

Advertisement

3.

Washington

That the founders of the great American collections were initially pessimistic about their ability to acquire major works of European art may strike one as quaint, considering what was in the end achieved. But in the case of sculpture, by which they meant preeminently Italian Renaissance sculpture, that pessimism was not far wrong. Consider what eluded them. No sculpture by Michelangelo or Ghiberti was acquired. One major Donatello, the luminous marble relief of the Madonna of the Clouds, entered the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. Also in Boston one major bronze by Cellini, the wonderful bust of Bindo Altoviti, came to the Isabella Stewart Gardiner Museum. There are minor works attributed to both of the latter artists in American collections: but in this context the word rare means rare.

Washington’s National Gallery once had half a dozen Verrocchios. Of these, three find their way into Butterfield’s book, two of them as doubtful and the other as possibly made in the master’s shop. This last (cat. no. 25) is the marble relief of a warrior, known as Alexander the Great. It is a classic Renaissance image, not least because, as an image, it seems to be the twin of a famous profile drawing of a warrior by Leonardo. Verrocchio made two bronze reliefs of Alexander and Darius for Lorenzo the Magnificent to give to the King of Hungary, Matthias Corvinus. They are now lost. In the Washington marble, and in the Leonardo drawing, we feel very close to what these reliefs must have been like. The word fantastic, applied to the armor in this and related images (the conch-like helmets, the dragon and bat wing designs, the medusa heads), seems appropriate. Vasari says that Verrocchio designed the armor for the reliefs “a suo capriccio.” Unlike most architectural caprices, Italian armor of a ceremonial kind falls not far short of Verrocchio’s and Leonardo’s wild imaginings.

It is good to begin a journey into Verrocchio in front of this marble relief, because it gives an opportunity to say goodbye to the problem of the relationship between Leonardo and his master. Butterfield refuses to get bogged down in this issue, which is rather like the question of the dedicatee of Shakespeare’s sonnets, in that it can drive a person unproductively mad. A tendency in the past was to find something good in the Verrocchio oeuvre and to attribute it, therefore, to Leonardo. Leonardo was certainly a sculptor, but the best way to go batty is to start looking for a sculpture by him.

Of the “uncertain” candidates, the bust of Giuliano de’ Medici (cat. no. 29) is apparently much restored and altered. It is a highly desirable trophy sculpture, sold by the Duveen brothers to Andrew Mellon. It is a perfect example of the Pierpont Morgan taste. More extraordinary is the putto (cat. no. 39) in unfired clay. Unfired clay! How could such an object have survived half a millennium, and why would it have been left unfired? The only reason I can see is that one would hesitate to fire a clay model (in case it exploded) before one had copied it into whatever medium one had chosen. The longer you leave a model to dry, the less likely it is to explode. But if you happen to die before making your copy of the model, then of course it is up to your heirs whether they send it to the kiln or not.

Butterfield cites a document which indicates that in the sixteenth century copies after fifteenth-century Florentine works were made in unfired clay, but he does not speculate about the reason for this practice. Whatever the putto is, and however you rate its modeling, it is astonishing that it has survived.

New York

Henry Clay Frick never owned a Verrocchio, but John D. Rockefeller did, and in 1961 he bequeathed it to the Frick (cat. no. 4), whose collection, in its perfectionism, suits it especially well. It is a marble bust of a young woman. There is a delicate problem relating to the sitter’s identity. Butterfield writes:

It has often been said that she is a member of the Colleoni family, perhaps even Medea, the beloved daughter of Bartolomeo Colleoni. This hypothesis is based solely on the premise that the pattern on the brocade of her sleeves includes testicles (coglioni), but the testicles in Colleoni’s heraldry have a distinctive shape (similar to an inverted comma) and clearly differ from the forms in the brocade. Consequently, this hypothesis is incorrect….

And in the catalog section of his monograph Butterfield repeats that “No known stemma of the Colleoni family has testicles in the form used in the heraldry of the present sculpture.” The layman is bound to feel provoked into replying, in the face of all this testicular certainty, that if the girl is wearing testicles on her sleeve (correct or incorrect), she must be trying to say something thereby. I assume, although Butterfield does not say so, that these brocade sleeves, with their decorative surfaces, could well have been colored and gilded.

The last of the American Verrocchios is in private hands, in the collection of Michael Hall, Esq. It is a bust of Christ (cat. no. 9), made apparently by a hybrid method, in which the clay is pressed against the sides of the mold, but the surface is later worked by the artist before firing. I have not seen it. It was Verrocchio’s achievement to create an image of Christ which proved extraordinarily influential and tenacious. The features are based on an apocryphal description attributed to Publius Lentulus, a Roman administrator of Palestine. The shoulder-length hair, the middle parting, the large nose, and the short divided beard all derive from this description, to which Verrocchio added high cheekbones and heavy eyelids. Once Verrocchio had developed this facial type, he seems to have stuck to it and to have promoted it in studio copies, of which around a hundred survive (indicating that perhaps thousands were once made). But this particular example seems to Butterfield to show the master’s intervention. And it does not show the intervention of the restorer, being both painted and gilded.

London

In London there are no finished objects by Verrocchio on view, only sketch-models—each one unique, and each illustrating a different aspect of a sculptor’s working practice. The first (cat. no. 24) is a plaster cast of a terra-cotta sketch which used to be the pride of the Kaiser-Friedrich Museum in Berlin, but which was destroyed in the Second World War. Or perhaps it was not destroyed. Perhaps it is even now in Uzbekistan. It represented the Entombment, and it was only ever known, in modern times, in a fragmentary condition. Perhaps it was always unstable or incomplete, one of those accidents of the kiln. The top half of the composition has come away—as if in great flakes. Two features of the relief would have convinced the early scholars of its authenticity—the type of features of Christ, and the beautiful elaboration of the folds of the garments. Verrocchio made intense studies of anatomy (and that generally means, in this period, the male anatomy), the results of which can be seen in the figure of the dead Christ. And he was obsessed with the expressive qualities of drapery, which he explored both in sketches such as this and in his drawings on linen.

Sometimes the bare notes on the provenance of an object are full of resonance for the history of our culture, and the career of this object tells us a poignant tale. It was bought in Florence by an Austrian collector in 1865. It was purchased in Vienna by Wilhelm Bode in 1888 and published soon after. I was told that it was placed for safety in some kind of artillery base during the attack on Berlin, and that this precaution ensured its destruction. Its survival in London as a plaster cast tells us what an exemplary object it was held to be.

The collections of the Victoria and Albert were inspired by an interest in the manufacturing process. That is why there are so many terra cottas, and why an object such as the sketch-model for a memorial to Cardinal Forteguerri (cat. no. 22) would have been acquired. It has not always been much liked, and sometimes has been denounced as a fake. One would have to imagine a forger interested in recreating an artist’s original design for a monument later built (in Pistoia) in quite a different way. Perhaps the reason people had their doubts was that if Verrocchio had lived to finish the monument in the way indicated by this sketch, it would have been a design without precedent, a dramatic scene in which a vision of Christ and the angels appears to the cardinal, in a manner prefiguring the Baroque.

Last in London is an object in a private collection we may not see, the terra-cotta modello for the executioner in The Beheading of St. John the Baptist (cat. no. 17; see illustration on this page). It emerged on the market in the Eighties, failed to sell, and has since been (like an actor) “resting.” This object is somehow connected with the silver relief made for the altar of the Florence Baptistry, but in contrast to Anthony Radcliffe, who first published it, Butterfield leaves some doubt what that relationship is.5 The object looks like a sketch-model. A garzone, a studio assistant, poses for the figure. He is nude, and in his right hand he holds a cloth (where the sword will go in the relief itself). Butterfield unfortunately does not illustrate the illuminating side view of this terra cotta, which shows how Verrocchio conceived the figure in such a way as to fit onto the sloping plane of the relief. It is fascinating to see the sculptor solving a technical problem of this kind at the same time as he is making his sketch. But where Radcliffe was quite clear what happened next (a piece-mold would have been taken, from which the figures could be cast), Butterfield introduces a major doubt. He tells us that the other figures in the relief (all of them made separately and then attached to the perspectival base) were not cast, as is often said, but repoussé, that is, beaten. About the figure of the executioner, he cannot be sure. But it seems extraordinary that a fundamental issue like this (the nature of the manufacture of an object) should still be in the balance.

Amsterdam

Telephone in advance to the Rijksmuseum. Not long ago, a Japanese visitor (who has probably since died of mortification) backed into Verrocchio’s 156-centimeter tall candelabrum (cat. no. 10) and knocked it over, damaging the rim. It is currently being restored. It was made for the chapel of the audience room of the Palazzo Vecchio, and bears a prominent inscription, “May and June 1468.” One document says that Verrocchio designed it in the form of a certain vase, but neither a vase nor a similar classical candlestick has been found. A sculptor’s job, if he had the skill to work in bronze, included the task of making bells, mortars, firedogs, cannon perhaps: any of the objects for which the same casting technique might be used. That is why, looking at objects such as this candelabrum, it is not entirely helpful to have a mind that makes a distinction between sculpture and the decorative arts.

This was an important commission, and a solemn object. The date refers to the two-month term of the Signoria, the chief magistrates. Butterfield tells us that during those two months there was only one important event, the signing of a peace treaty that brought to an end the Colleoni War in which Florence, Milan, and Naples fought against Venice and its condottieri. For Florence, the significant outcome of the war was the defeat of a group of Florentine exiles, and the consequent consolidation of the power of the Medici. Presumably for the gonfaloniere who inspired the commission and set the fee, the simple dates alone would signify to all who saw them the defeat of conspiracy and the evolving destiny of the ruling family. The sculptor appears, then, as the agent of Medici propaganda—an aspect of his work which Butterfield’s study brings very much to life.

Paris

There are two little terra-cotta plaques of angels (cat. no. 23) in the Louvre. Many experts say that they must be by different hands. I wish I could see this difference. When the plaques were restored in 1959, they were found to be of irregular shape and to have had pairs of holes drilled in them—to hang them up in the shop, no doubt. They were working ideas (although brought to a wonderful finish: they are among the loveliest terra cottas of their century) and were very probably produced during the work on the Forteguerri monument, although the label in the Louvre says that this is not so. Butterfield says that the one on the left is by Verrocchio, but that the one on the right should be attributed to an anonymous member of the workshop, being too weak to be by Leonardo, as one scholar had hoped.

The assumption here is that Leonardo was a very good sculptor indeed. No doubt he was, but there is no comparative work by him to go on.

Berlin

The German capital has one Verrocchio left, a terra-cotta statuette of a sleeping youth in the Staatliche Museum (cat. no. 12). It has periodically been offered a title—this is Adam, this is Abel, this is Endymion. But it seems wrong to seek a nude sleeper as a subject. Just as he did with the executioner, Verrocchio could have been studying in the nude a figure who would later be clad. That is why it is not far-fetched to suppose that this might be a study for a sleeping soldier in a Resurrection—even if it does not conform to the Resurrection relief Verrocchio actually produced (see below). Some terra cottas from this period survived because they proved useful in churches or chapels. The fact that this one survived indicates that there were collectors who were happy to give it house room, since it would never have fitted in a church.6 Giving it a title such as Endymion suggests that it was the practice of sculptors to make such statuettes, for art’s sake, for a domestic setting. But it is by no means certain that this was yet the case. It is so easy to forget that our idea of early Florentine interiors is formed by clever turn-of-the-century reconstructions—the Horne Museum, the Bardini, the Palazzo Davanzati. In such a setting, it would seem quite natural to take a statuette such as this one and place it on a table, on a piece of plausible brocade. But that might well be an anachronism, startling to Verrocchio’s generation, although less so to the one that followed.

Venice

“When it has been done by a truly great man, whose life and strength could not be oppressed…” But the Equestrian Monument to Bartolomeo Colleoni (cat. no. 26; see illustration on page 27) proved the death of Verrocchio, according to Vasari (he died of a cold caught during the casting). What is more, in Butterfield’s estimation, rather more of the statue can be attributed to Alessandro Leopardi than has always been recognized. Leopardi signed the monument prominently, in what I had always assumed to be an act of outrageous appropriation. But if Butterfield is right, Leopardi did all the casting and would have prepared the wax casting models. Though most of the horse is by Verrocchio, the tail is by Leopardi. Though the pose and conception of the figure is Verrocchio’s, the decorative surface of the armor and saddle and the finish of the head itself are, Butterfield thinks, in the Venetian rather than Florentine idiom.

Butterfield is more disparaging about the face than one might expect—it is after all one of the most famous faces in statuary. It was modeled on that of the emperor Galba, but is given an expressiveness that surely links it to the aesthetic Verrocchio shared with Leonardo. Butterfield tells us that the word for condottiere in the Latin texts of the time is imperator—the same as the word for emperor, and the condottieri were considered the equals of the great Roman generals and emperors—a level of esteem that vanishes in modern English if we translate condottiere as mercenary captain. The popularity of the Colleoni monument with the Victorians (the head can be examined at close quarters in plaster cast at the V&A) no doubt has something to do with that whiff of villainy emanating from the features. A condottiere could and would change sides—an act no Victorian soldier could begin to contemplate for himself, but might enjoy imagining in the past, that villainous Italian past which flashes from the pages of Ruskin and Browning.

But the Colleoni statue is not a monument to villainy. It is one of a series of equestrian monuments, painted, in stone and (in the most closely comparable, Donatello’s Gattamelata in Padua) bronze, which were epideictic in character. They were exhortations to virtue, examples for the citizenry to follow. Colleoni had wanted his statue erected in St. Mark’s Square, but the Venetians had a general ban on monuments to individuals either inside St. Mark’s or in the piazza. The idea that they circumvented the terms of the will (a piece of Venetian villainy) by placing it in front of the Scuola de San Marco (in the Campo de SS. Giovanni e Paolo) seems undermined by Butterfield’s observation that the Dominican Convent served, during the Renaissance, as the Pantheon of the Venetian Republic. By the time of the Colleoni monument, fourteen doges were buried there. Though it now seems a little off the beaten track, in its day the site would have been one of immense prestige.

Pistoia

Bad lighting and the long lunch hours of the sacristan (12 to 4), plus the fact that it was never finished by Verrocchio but was later cobbled together in an inappropriate baroque framework—all this has led to the neglect of the Forteguerri monument in the San Zeno church (cat. no. 21). But the photographs in Butterfield show it off admirably, and we have already seen in the terra-cotta models in London and Paris what the ensemble was supposed to look like and how its component parts were developed. It has no forbears in funerary sculpture, and Butterfield suggests that Verrocchio enjoyed a certain freedom partly because he was making a cenotaph rather than a tomb, and partly because Pistoia was provincial, and smaller cities tended to be less restrictive. The cardinal was to be seen kneeling in prayer, while above his head Christ appeared in a mandorla, held aloft by angels in the ultimate swirling robes, while Faith, Hope, and Charity dance attendance on the prelate. Because the figure of Forteguerri was not satisfactorily completed, we cannot tell how far Verrocchio intended to push the drama of the scene, but it is this sense of drama in what remains that makes one think forward to the Baroque. Blame Lorenzo de Credi for not carrying out his commission to finish it.

Florence

Bells were among the things a sculptor might expect to make—anything from handbells to full-size church bells, involving immense amounts of work (and investment). The lost bell Verrocchio made for a Vallombrosan foundation took four years to complete. A bell in San Marco, Florence (don’t expect to see it however, as it is under restoration), has been attributed to Verrocchio (cat. no. 2). It was known as La Piagnona, because it was used to call the followers of Savonarola—the piagnoni—to San Marco. Butterfield points out that during the Bonfires of Vanities of 1497 and 1498, a great many works of sculpture were destroyed, particularly busts of beautiful women. So it is highly likely that this, a work of Verrocchio’s, summoned the piagnoni to destroy works by Donatello, Verrocchio, and many other great artists of the early Renaissance. The bell did not go unpunished. In 1498 it was taken down and carted through the streets, whipped by the city’s executioner, and sent into exile for ten years.

Another pointless quest at the moment is the viewing of the tomb of Fra Giuliano Verrocchio in Santa Croce (cat. no. 27). The theory is that Verrocchio, who was born Andrea di Michele Cione, might have made the tomb of this friar, and for some reason (such as that the tomb had made him famous) taken the man’s name. Like most floor slabs of the period, the tomb has taken much wear and tear. But still there are optimists who say that the bony feet are bony like other Verrocchio feet. Unfortunately the bony feet are currently buried under planks and scaffolding.

One of the loveliest and most popular works of the Florentine Renaissance is the bronze statuette of the putto with a dolphin in the Palazzo Vecchio (cat. no. 20; see illustration above). This was brought in from a villa to the courtyard of the palazzo, where it was installed by Vasari on a fountain. Like so many Florentine sculptures which used to be in the open, it was later taken indoors and now sits in a small room upstairs in the Palazzo Vecchio, a room so small that one is unable to walk around it. And this is a particular shame in that rather empty set of rooms, because the statue in question is the first figura serpentinata of the Renaissance. That is to say, its turning form was designed to make it a perfect composition from all points of view. Butterfield rejects the idea that it once had a mechanism that caused it to revolve, and this seems a pity, although he is no doubt correct.

Less and less of the art of Florence is allowed to remain where it used to be. The silver altar from the Baptistry sits in the Museo del Opera del Duomo, almost unrevered, and one can examine it at leisure. Verrocchio’s panel (cat. no. 16) tells a story not from the Bible but from a fourteenth-century life of John the Baptist:

The officer went to the prison and with him an extremely base youth with a very sharp sword…and crying he said: “Servant of God, forgive me for the injustice that I must do, and pray to God for me telling him that I do this unwillingly.” And Saint John kneeled down with a cheerful face and said:”Brother, pray to God that he forgive you, and I will forgive you as much as I can….” And he stretched out his neck, that gentle lamb, and his head was cut off. And all the prisoners and all the guards began to cry with the loudest wails, and they began to curse the girl and her mother, for they heard how she had asked for [his head].

The “extremely base youth” is the figure for which the terra cotta was found in London. The reluctant officer, resplendent in his fantastic armor, places his hand on his chest in a gesture which Butterfield tells us elsewhere always indicates intense emotion. His model, and that of the youth with the salver who raises a hand in a gesture of compassion, are the ones that used to belong to Baron Adolphe Rothschild, which the family refused to have photographed, and which have been apparently lost.

The Orsanmichele, half church, half grainstore, is having all its original statuary (including works by Ghiberti, Donatello, Verrocchio, and Giambologna) removed from the niches on its façade to a room above church level. Christ and Saint Thomas (cat. no. 8) were cleaned and restored as part of this process and are already upstairs. Those who saw the group when it was exhibited at the Met in 1993 will know that the figures are reliefs rather than statues in the round, but they were so constructed as to make this impossible to guess, even though they boldly overflow their allotted space.

Cast bronze emerges from the mold with a rough surface—the bell of San Marco, could we see it, is what Verrocchio looks like unchased: i.e., with the surface rough as it would emerge from the mold. The restored figures of Christ and Saint Thomas set the standard, show us what the very best Renaissance bronze came to look like when its surface was laboriously smoothed by the chaser’s art. Where the right foot of Saint Thomas has protruded from the niche, that luxurious surface is lost to verdigris. But for the most part the chocolate richness of the bronze has been reinstated, the gilding rediscovered, and the folds flow luxuriously. The statue of Colleoni, even if restored (which it has not been in this century), will never come back with this intensity.

One enters the Verrocchio room of the Bargello to be greeted by a sight seldom seen today—a shaft of winter sunlight falling directly onto the painted surface of the crucified Christ (cat. no. 14). For a moment one is too dazzled to see this newfound sculpture clearly. One turns away, and one’s gaze falls at once on the Careggi Resurrection, a painted terra-cotta relief showing the same type of face of Christ, as if offering confirmation of the genuineness of the crucifix. The relief (cat. no. 11)is painted, not glazed. Much damaged, it is another example of that “non-classical” approach to using different mediums; if we were able to see the relief in the full freshness of its paint, it might yet shock.

The Resurrection scene depicted is apocryphal. Nowhere in the Bible do the soldiers actually see the resurrected Christ. But in an account called the Acts of Pilate they do, and it is a scene that found its way into the liturgical dramas of Verrocchio’s day. Butterfield quotes a stage direction from one of these:

Suddenly Christ is resurrected with earthquakes and explosions. Each of the soldiers is like a dead man and Christ appears with the pennant of the Cross between two angels.

So the scene represented in the relief is one that would have been familiar from popular drama. That connection between popular drama and the representational arts must have been intimate (there is another clear example in Donatello’s relief of the Ascension), but it is easy to forget. People must have looked at such reliefs and thought: I know what this is because I have seen it performed.

Turning back to the crucifix, which is displayed at an angle to allow you to examine it from close to, but as if it were high on a wall, you see (what is not obvious from the photographs) that its mouth is open and its teeth visible. Is Christ intended to be calling out the last words from the Cross?

A third of Verrocchio’s oeuvre is held by the Bargello, but if you take Butterfield as a guide you have a slightly different list from the one indicated by the museum labels (astonishingly enough there is no proper catalog of the Bargello’s sculptures, although the minor art of plaquettes is admirably served). The bust of a lady holding flowers to her breast (cat. no. 15), which with the Frick bust belongs to that category of portraits of contemporary beauty that got chucked onto the Bonfires of Vanities, should be an object of secular pilgrimage. This is what Florence meant by beauty. The terra-cotta Madonna and Child (cat. no. 13) is another exemplary work (the marble version of the same subject is relegated to the workshop).

A striking marble bust of Francesco Sassetti, labeled in the plinth as being by Antonio Rossellino, was assigned by John Pope-Hennessy to Verrocchio’s early years. Butterfield follows his teacher and mentor in this view, although his reasoning has shifted. A part of Pope-Hennessy’s case was that the heavily drilled irises and lightly incised pupils were characteristic of Verrocchio, and he compares them to the “penetrating glance” of the Colleoni. But that same “penetrating glance” is seen by Butterfield as typically Venetian work.

A more striking disagreement between teacher and student is over the attribution of the little bronze known as “Il Pugilatore” (cat. no. 19) but labeled “Uomo di Paura.” Is it a pugilist or a man of fear? And who is it by? The earliest attribution was to Pollaiuolo. Subsequently everybody has had a go, and it has been a Bellano, a Camelio, a Riccio, and a Sperandio, successively or simultaneously. Pope-Hennessy knew that Donatello had made small bronzes, and he thought this the best candidate for a surviving statuette by his hand. Butterfield, not unconvincingly, finds affinities with Verrocchio. But the statuette remains a puzzle. Small bronzes are a puzzle.

Verrocchio’s David (cat. no. 5; see illustration on page 28) suffered an interesting fate. The detachable head of Goliath at its feet (and in the wrong position perhaps) was separated from it during the seventeenth century, and the figure was identified first as Mars, and later as a young warrior. Only in the mid-nineteenth century did it turn back into a David, and get back its Goliath trophy. Millions of students and tourists must have gazed on this iconic work thinking it one of the eternal verities of art. But these eternal verities have a checkered history.

Few works by Verrocchio have remained in their allotted place. The monuments in Venice and Pistoia have not been moved; neither has the lavamano, an elaborately carved basin (cat. no. 1) to which he contributed a section, which has remained in the Old Sacristy in San Lorenzo, although the problems of its plumbing have meant that it was always being mucked around with. But two more of Verrocchio’s works remain where they always were, and always were supposed to be. One is that mysterious tomb of Giovanni and Piero de’ Medici of which one side looks into the old sacristy and the other onto an adjacent chapel, from whose regular offices the dead might find benefit.

The last is the tomb of Cosimo de’ Medici (cat. no. 6). Ruskin said of the Doges’ Palace in Venice, “It is the central building of the world.” But San Lorenzo was the central building of the Medici world, and surely the central building of the Renaissance. And Cosimo’s supposedly modest monument, a design of ellipses within a circle within a square, placed on the floor in front of the high altar, lies at the center of that central building—the universe in a diagram of marble, bronze, and porphyry.

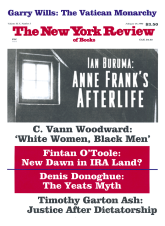

This Issue

February 19, 1998

-

1

W.R. Valentiner, Studies of Italian Renaissance Sculpture (London:Phaidon, 1950), p. 182.

↩ -

2

Within two years of Valentiner’s publishing this discovery, the director of the Schlossmuseum exchanged the candelabrum, among other objects, for part of the Guelph Treasure, which included German medieval goldsmith’s work of the highest quality and which, particularly in the political and cultural climate of the time, would have proved irresistible.

↩ -

3

Burlington Magazine, December 1994.

↩ -

4

The Stones of Venice, Part Three.

↩ -

5

See Anthony Radcliffe, “New Light on Verrocchio’s Beheading of the Baptist” in Verrocchio and Late Quattrocento Italian Sculpture, edited by Steven Bule, et al. (Florence: Casa Editrice Le Lettere, 1992).

↩ -

6

Apart from a noble patron, the most obvious type of collector of the period would be an artist. Artists and goldsmiths are known to have kept casts of exemplary works, including the Verrocchio cup mentioned by Vasari above.

↩