1.

Even those without nostalgia for the cold war will admit that it had some moderating elements. For more than a half-century the character of the bi-polar Soviet-American confrontation protected Europe and North America from conflict. For the most part, violence and danger were relegated to regions where confrontation was not direct. The major fighting was in Asia, and never really threatened to escalate to global war. The only dangers of such escalation, apart from some heart-stopping moments around Berlin, were in Cuba, where Soviet Prime Minister Khrushchev tried to install nuclear weapons in 1962, and in the Middle East, when the United States and the Soviet Union went on nuclear alert following the 1973 Egyptian-Israeli war.

In contrast to the first half of the twentieth century, with its two devastating world wars, the cold war period was marked by a stable, if tense, equilibrium. This equilibrium had a suppressive effect on ethnic tensions in Europe. The exigencies of World War II, followed by armed peace, made it easier for Josef Stalin and his successors to subdue the restive nations of the Soviet Union and intimidate the Eastern European appendages of the Soviet empire. In Yugoslavia, where over half a million Yugoslavs had been killed by their own countrymen during the war, Marshal Tito balanced off local ethnic groups, imprisoning nationalists who violated the doctrine of “brotherhood and unity.” In neither the Soviet nor the Yugoslav case, however, did the rulers “solve” the ethnic problem; as soon as the respective regimes weakened, ethnic conflicts again arose to help destroy them.

Nor was the Western camp conspicuously successful in treating its ethnic problems during the cold war. The membership of Greece and Turkey in NATO failed to prevent their war over Cyprus. And fighting between Catholics and Protestants in Northern Ireland began in 1969, and intermittently continued for twenty-nine years.

In the rest of the world, contrary to common wisdom, the cold war probably had more of a provocative effect on local tensions than a pacifying one. In some cases great power competition prolonged conflicts which had begun as a result of decolonization, as in the long-running and murderous civil wars in Angola and Mozambique, and in Vietnam as well. In other cases ethnic war became a test of will between the Soviet Union and the United States, as in Afghanistan, or was stimulated for ideological reasons, as with the Reagan administration’s support of Miskito Indians in Nicaragua.

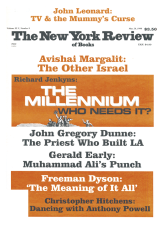

This Issue

May 28, 1998

-

1

Carnegie Commission on Preventing Deadly Conflict, Preventing Deadly Conflict (Carnegie Corporation of New York, December 1997), pp. 12, 26.

↩ -

2

Samuel P. Huntington, The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order (Simon and Schuster, 1996), pp. 138, 260-262, 281-291.

↩ -

3

Charles Dickens, A Child’s History of England (Oxford University Press, reprinted 1987), p. 338.

↩ -

4

Quoted by Ignatieff in The Warrior’s Honor, p. 38.

↩