In the modern history of Switzerland, the heroic days were those of 1847 and 1848. It was then that the Swiss liberals founded a new nation by defeating an attempted secession of the Catholic cantons in a short but crucial conflict, the Sonderbundskrieg, and then by providing the restored union with an effective constitution and the institutions that would help make it work.

No less remarkable than this impressive beginning was the country’s ability to defend its independence from external threats during its first vulnerable decade. These were perilous days for the new federal state. The revolutions in Central Europe in 1848 and 1849 posed in its most acute form the problem of reconciling Switzerland’s policy of neutrality with its long tradition of providing asylum for political refugees. The conservative powers of Europe, irritated by the proud independence of the new federal state’s foreign policy, seemed on more than one occasion to be searching for a pretext for intervention. From this eventuality Switzerland saved itself by stubbornness and inspired diplomacy, while at the same time giving refuge to the fragments of the defeated revolutionary army in Baden and those who had fought on the barricades of Dresden and Milan. A hundred years later Max Frisch’s stern critic of his country’s fortunes, Anatole Stiller, was to say of its founders, “In those days they had a blueprint. In those days…they rejoiced in tomorrow and the day after. In those days they had a historical present.”1

The 150th anniversary of the Swiss federal constitution will come in September of this year, but it is to be doubted that it will be quite as self-celebratory an occasion as it would have been in quieter times. Since the beginning of this decade the Swiss government has been buffeted by charges, from domestic and international critics alike, that its conduct during the Second World War systematically betrayed all of the principles laid down and defended by its founding fathers. Specifically, the Swiss authorities are accused of pretending to a status of neutrality which was from the beginning fraudulent, slanted as it was in favor of Germany, and, with respect to the right of asylum, of following a highly selective immigration policy, which in particular discriminated against Jewish refugees; while the Swiss banks are accused of helping finance German aggression by laundering Nazi gold that had been looted from countries throughout Europe.

1.

From the beginning of the war the Swiss government was attentive to the desires of its dangerous northern neighbor and, particularly after the fall of France, anxious not to annoy its unpredictable leader. This led it to be deferential in many ways: it yielded to the German insistence on a Swiss blackout that would confuse Allied bombers, for example, and adopted a press policy that forbade the publication of items that might be offensive to the Germans. But these were small things in comparison with its tolerating a policy of financial collaboration between Swiss and German banks that facilitated Germany’s military operations and may very well have prolonged the war.

This is the aspect of Swiss behavior that has done the most to cause and sustain the current discussion of Swiss wartime policy, and it is the principal theme of the authors of the four books discussed here: Jean Ziegler, a Socialist member of the Swiss parliament and a longtime opponent of the banking community; Adam LeBor, a correspondent for the London Times and The Jewish Chronicle, who lives in Budapest; Isabel Vincent, a reporter with the Toronto Globe and Mail and the winner of several awards for investigative journalism; and Sidney Zabludoff, an economist who works for the World Jewish Congress. What they have written is complementary and sometimes overlapping. Of the four books Vincent’s is the most critical and the one with the widest perspective; she reminds her readers frequently that they would do well to consider the wartime sins of their own governments before rushing to judgment on Switzerland. Ziegler’s language is often colored by his feeling of betrayal by his own leaders but, perhaps because of this, his book is the most readable. LeBor is so intent on seeking the big story that he is not always critical enough of his sources, and he sometimes, with headlines like “The Financiers of Genocide,” promises more than he delivers; but he makes up for this by what he has to say about cooperation between the Swiss and German intelligence services and about the resistance of individual Swiss officials to their country’s immigration policy.

Taken together, these works can read as a kind of commentary on the remark of one of the characters in Gottfried Keller’s story “The Little Banner of the Seven Upright Ones,” written in 1860. Alluding in general terms to the state of values in the country, this person says, “Luckily there are no terribly rich people among us; wealth is fairly enough divided. But just let fellows with many millions appear, who have political ambitions, and you’ll see what mischief they’ll get up to!”2 It was precisely such types, in the guise of bankers with political connections, who, in Ziegler’s words,

Advertisement

fenced and laundered the gold stolen from the central banks of Belgium, Poland, Czechoslovakia, Holland, Luxembourg, Lithuania, Albania, Norway, Italy, and elsewhere. It was they who financed Hitler’s wars of conquest. Switzerland, the world’s only neutral financial center of truly international standing, accepted Hitler’s looted gold throughout the war years in payment for industrial goods or as bullion that was fenced and laundered and exchanged for foreign currency or traded off in other financial centers under new, “Swiss” identity. But for Switzerland’s financial services and the willing fences of Bern, the zealous gnomes, Hitler would not have been able to wage his rapacious wars of conquest. Swiss bankers supplied him with the requisite foreign exchange.

There seems to be no doubt about the essential truth of these accusations. With respect to the activities of the banks, for example, Sidney Zabludoff’s circumstantial study of the movement of Nazi gold during the war, commissioned by the World Jewish Congress, proves convincingly that

Swiss banking institutions played the pivotal role in handling the looted gold sold by the Nazis. They were the initial recipient of $438 million or 85 percent of all gold Germany shipped to foreign locations from March 1938 [the date of the Austrian Anschluss] to June 1945. In most cases, this precious metal was shipped from the Reichsbank to its depot account at Swiss National Bank (SNB), with the heaviest flow occurring from the fourth quarter 1941 [after the invasion of the Soviet Union] to the first quarter of 1944.

It all flowed back again in the form of goods and currency that could be used for the benefit of the German military establishment.

To what extent can it be said that this policy enjoyed popular support? There was a wartime saying, quoted by LeBor, that ran: “For six days a week Switzerland works for Nazi Germany, while on the seventh it prays for an Allied victory.” This is ungenerous without being inaccurate. It was not only the bankers who profited from the trade with Germany. Many ordinary Swiss citizens earned their wages from making things that Germany needed and paid for in looted gold. Ziegler argues that many of these people did not particularly like what they were doing and that some men and women of all social classes and all cultures and languages opposed the government’s policy whenever and however they could, pointing to the Swiss journalists who risked and often sacrificed their careers by defying the official, pro-Hitler censorship of the press.

He may be right, but the fact is that there is no way of estimating accurately the feelings of the Swiss people during the war. As for the Allied governments, they knew of the traffic between Germany and Switzerland but were unable to prevent it and were aware that complaints might risk the undeniable services that the Swiss government provided them (whether by representing their interests and protecting their nationals in occupied countries, or by acting as a conduit to Berlin and Rome when it was necessary to communicate with them officially, or by turning a blind eye to the activities of Allen Dulles’s OSS unit in Bern). The Allies thus found it politically expedient to assume that the Swiss people were on their side. In a speech in 1944 Winston Churchill said:

Of all the neutrals Switzerland has the greatest right to distinction. She has been the sole international force linking the hideously sundered nations and ourselves. What does it matter whether she has been able to give us the commercial advantages we desire or has given too many to the Germans to keep herself alive? She has been a democratic state, standing for freedom in self-defence among her mountains, and in thought, in spite of race, largely on our side.

In Allied capitals it was recognized also that the Swiss government was not exactly a free agent, and that resistance to Hitler’s will, on anything that he considered important, might very well lead to a German invasion of Switzerland. Today, with the memory of Hitler and his Blitzkriege far behind us, there is some disposition to assume that the Führer wanted hard currency so badly that invasion of Switzerland was out of the question. One of LeBor’s sources is quoted as saying that Hitler depended so much on Bern to keep the Nazi war machine rolling that anyone “who even suggested the possibility of invading Switzerland would have been sent to the Russian front.” But Ziegler believes that if the Swiss had refused to go along with Hitler’s wishes after the fall of France, it “would very probably have suffered the same fate as Austria or Czechoslovakia”; and Vincent reminds us that in 1940 the German army already had a plan for an invasion, Operation Tannenbaum, and in 1943, Himmler was a strong advocate of a military coup. Hitler’s reputation for sudden unexpected action (the snatching of Mussolini from the Gran Sasso in 1943 and the strike through the Ardennes in 1944) must have been enough to keep Swiss apprehension alive and to counsel against any change in their policy of financial support.

Advertisement

That Swiss collaboration was tremendously important to the Nazi war effort seems beyond question. Whether it prolonged the war is a plausible but essentially unprovable hypothesis. That the American offensive in Northern Italy ground to a halt along the Rimini- Bologna-Pisa line in April 1944 because the enemy was equipped with vast supplies of arms, ammunition, spare parts, and gasoline transported to it by way of Switzerland, as Ziegler mentions, proves nothing one way or another. Battles are not won by supplies or money alone, and this Clausewitzian truth is probably applicable to the question of the duration of wars. In any case, this is a question that cannot be answered unless we have a lot more information than is currently available.

2.

In May 1995, on the fiftieth anniversary of the end of the Second World War, Kaspar Villiger, president of the Swiss federal state and minister of defense, delivered a speech in the Bundeshaus in Bern in which he dilated on Switzerland’s behavior during the war and admitted that it was not in accordance with its ideals. Among other things, he spoke of the restrictions placed upon the right of asylum, particularly for Jewish refugees.

Would Switzerland have been threatened with extinction had it been more definitely receptive to victims of persecution than it was? Was this question, too, affected by anti-Semitic sentiments in our country? Did we always do our utmost for the persecuted and disenfranchised?… Fear of Germany, fear of foreignization by mass immigration, and concern lest the anti-Semitism that also existed here receive a political fillip—these sometimes outweighed our tradition of asylum, our humanitarian ideals. We were also prompted by excessive timidity to resolve difficult conflicts of interest at the expense of humanity. In introducing the so-called Jewish stamp [on passports], the Germans were acceding to a Swiss request. That stamp was approved by Switzerland in 1938. An unduly narrow conception of the national interest led us to make the wrong choice.

These admissions, doubtless prompted by the growing domestic and foreign scrutiny of Switzerland’s war record, were accompanied by an insistence that all those who had been responsible for immigration policy had acted “solely and exclusively in the interests of the country’s welfare as they perceived and saw it,” and that to castigate them now would be unjust. However that may be, history will record that, while Switzerland in the course of the war took in 295,000 refugees, including about 25,000 Jews, they turned away 30,000, most of them Jews, in collusion with the Germans and in violation of international law, and that in doing so, knowingly or not, they consigned most of them to death in the extermination camps.

This was a form of collaboration more shameful than the traffic in gold, and there were Swiss officials who risked their careers to protest against it. One of these was Commandant Paul Grueninger, a career police officer in the Saint Gall canton on the Austrian border. In 1938, after the Anschluss, when the government closed the frontier to the hordes of Austrian Jews seeking refuge in Switzerland, Grueninger allowed 3,600 of them to enter his country by falsifying their papers. When this was discovered, he was dismissed, tried for forgery and insubordination, and sentenced to the loss of his position and the forfeiture of all retirement and severance payments. Nor was this punishment corrected after the war came to an end. Until his death in 1971, Grueninger remained without a suitable position and was harried by a smear campaign which accused him of having acted for personal profit.

3.

Meanwhile, the financial collaboration between Switzerland and Germany continued, unaffected by a January 1943 inter-Allied prohibition of looting and laundering of the treasuries of occupied countries. In 1944, the United States and Great Britain mounted an intelligence effort, Operation Safehaven, to monitor the movement of Nazi gold to Switzerland, but according to Isabel Vincent, this was not very effective because Dulles’s OSS unit in Bern showed no enthusiasm for the task and the British, conscious of the fact that they would need the assistance of Swiss banks to get loans on favorable terms in order to rebuild their shattered economy at the war’s end, did not wish to alienate them in advance. Even when an American mission headed by Lauchlin Currie negotiated an agreement in March 1945 by which the Swiss undertook to cut off trade with Germany and freeze German assets in return for renewed supplies of the coal whose delivery had been disrupted by the liberation of France, the Swiss dragged their feet in implementing it. One month after it was signed, and one month before the German unconditional surrender, the Swiss accepted three more tons of looted gold. While much of the world was waiting in breathless anticipation for Hitler’s imminent fall, the Swiss banks seemed intent only upon squeezing as much profit as possible from the Nazi connection before that should happen.

Nor can it be said that this behavior backfired on them. When, in consequence of proposals made by the Paris Reparations Conference in November and December 1945, Allied and Swiss negotiators met in Washington in February 1946 to discuss the status of German assets in Switzerland, there was some expectation that the Swiss would be made to pay for their collaboration with the defeated enemy. But the shadow of the gathering cold war was already falling over their deliberations, distracting the Allied negotiators and forcing them to think of how they might soon need Swiss assistance against the Soviet Union. The Swiss delegates, on the other hand, led by Walter Stucki, deputy head of the Foreign Ministry, were tough and immovable, arguing that in the recent conflict—in which, they intimated, there had been no moral difference between Germany and its opponents—they had stood above the fray as neutrals, working in accordance with international law. They saw no reason why they should be called upon to share their wartime profits with anyone.

At the beginning of the Washington conference, there had been some talk of forcing the Swiss to hand over all German assets held by their financial institutions as reparations. After sixty-eight days of grinding negotiations, during which, as Ziegler says, Stucki displayed “an astonishing degree of arrogance and self-righteousness,” the Allies took what they could get: 250 million Swiss francs ($58.1 million) in full settlement of all claims relating to Switzerland’s transactions with the German Reichsbank. This sum was, moreover, to be paid not as reparations but as a voluntary contribution to the reconstruction of Europe. To understand what a victory this represented for the Swiss negotiators, we must note that Zabludoff’s careful calculations lead him to the conclusion that the amount of looted gold handled by the Swiss during the war period was $275 million. He adds, however:

If gold forcibly purchased from German citizens during the 1930s is also classified as looted, then the Swiss would have taken in some $375 million in looted gold. All these figures are much greater than the $58 million in gold the Swiss turned over to the Allies after the war. To understand these numbers in today’s prices, they must be multiplied by about 10. Thus, after subtracting its modest post war payment, according to post-war agreements Switzerland would now be obliged to pay some $2 to $3 billion to compensate for taking in looted gold.

The Washington accord was bitterly attacked by some American politicians. Senator Harley Kilgore had chaired hearings of the Senate Subcommittee on War Mobilization in June 1945 to look into the possibility of Swiss financial institutions bankrolling German rearmament. Long a champion of cracking down on the Swiss, Kilgore now wrote to President Truman that

justice, decency and plain horse sense require that the allies hold Switzerland responsible for all of the…looted gold which they accepted from the Nazis and reject their proposition of settling for 20 cents on the dollar.

It was, as we now know, considerably less than that but, even if that had been known, there was no likelihood that Truman would do anything about it. The US was wracked with strikes, and the Soviets were in northern Iran; Swiss affairs were now in the back pages of the newspapers.

And there they remained for over forty years. Intermittently, the attentive reader might come upon a reference to a smoldering dispute that had not been touched upon in the Washington accord: the question of access to dormant accounts of people, mostly Jews, and many of them victims of the Holocaust, which was being impeded by Swiss bank secrecy regulations and obstructed by Swiss bureaucrats. The Jewish organizations that might have made this a major issue had until very late in the cold war been engrossed by other problems. As one of their representatives said, they had first to deal with the fate of people displaced as a result of their experience in the concentration camps, and then to fight for the state of Israel; and after that came reparations from Germany and other things. “There were always other priorities that took a long time to overcome.”

In 1954, the Israeli government urged the Swiss government to deal with the question of dormant accounts, but it was only in 1962 that the banks were authorized to break their rule of secrecy in order to identify unclaimed funds of foreigners persecuted for racial, religious, and political reasons. A subsequent inquiry identified only 961 accounts of this nature, whose contents were returned to their rightful owners. This was clearly unsatisfactory, but nothing was done to correct it.

Switzerland became news again at the beginning of the 1990s for a number of reasons. In the first place, the end of the cold war revivified the movement toward European integration and raised the question of Switzerland’s role in the new Europe. In Switzerland this caused a protracted debate between Europeanists and traditionalists. This led Adolf Muschg, one of the country’s most distinguished writers, to challenge the viability of neutrality and to call for a return to the vision of 1848, when, he said, Switzerland was

a model for the continent, which for a while had all the European powers against it, but the wind of history in its favor. Today, the Musterländchen, which has become sated, must learn to have a new model, the little Gold-Majesty Switzerland must thoroughly repudiate its consciousness of being a special case in order to become again what it once was—and what it must otherwise become in any case, only without a will of its own and the pride that comes from independent action—an integral part of Europe, jointly sharing its hopes, jointly responsible for its success. That will require of my much blessed country a hard piece of work and the overcoming of a good deal of Angst, the Angst of those who have much property and a high degree of security.3

Despite this appeal, the Swiss people rejected membership in the EC and reaffirmed their neutrality in 1992.

Then came the continent-wide preparations for the celebration of the fiftieth anniversary of the end of the World War II, in which the Swiss government initially decided not to participate on the grounds that it had been neutral. This caused much controversy and stimulated, not least of all among local historians—like Jacques Picard, author of an important study called Die Schweiz und die Juden, 1933-1945—a critical examination of the nature of Swiss neutrality during the war.

Finally, in September 1995, Edgar Bronfman, president of the World Jewish Congress, decided to take up the cause of Holocaust survivors who had been living behind the Iron Curtain but were now in a position to demand the return of family assets which they believed had been deposited for them in Switzerland by relatives or friends during the Nazi period. Bronfman was authorized by the Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin to act on behalf of these putative depositors, and when he was received coolly and unresponsively by the Swiss Bankers Association, he resolved, as he later said, to “get their attention.”

This he did by enlisting the services of Senator Alfonse D’Amato, the chairman of the US Senate’s Banking Committee, who was quick to see that his sagging political fortunes might be revived if he took up the cause of Holocaust survivors. The senator’s dramatic hearings in Washington were marked by excessive sound and fury, by sensational disclosures that sometimes turned out to be neither new nor correctly stated, and by fulminations and extravagant threats to boycott all Swiss banks. But they threw so much unflattering light upon Switzerland’s wartime practices that in the end the bankers and the government decided that it would be wise to stop stonewalling and complaining about unfair attacks and to choose instead a strategy of conciliation. They agreed to cooperate with a committee headed by Paul Volcker, former head of the Federal Reserve Board, which would study Swiss banking practices in the Nazi period and audit the records of 450 Swiss banks. They undertook to engage in an energetic search for holders of dormant accounts. And, in a move that astonished many in Europe and elicited words of praise even from Bronfman and D’Amato, they established a fund of 7 billion Swiss francs ($4.7 billion) to support persons in need who had been persecuted for reasons of race, religion, or politics or were otherwise victims of the Holocaust.

Ordinary Swiss citizens were less impressed by this resolution of the dispute. In general, they appear to have divided. Some took comfort in the feeling that the extensive airing of wartime practices might be good for the country by leading to a disenchantment with neutrality and a willingness to reconsider the question of joining Europe. Others felt that the tactics employed by Bronfman and D’Amato had demeaned the image of Switzerland unfairly and perhaps irretrievably. After the Washington hearings there was a perceptible increase in anti-Semitic incidents in the country, although anti-Semitism was by no means the sole motivation of a widespread sense of outrage. “We were not consulted,” the president of the Swiss Federation of Jewish Communities has said, “and this led to all types of distortions. Switzerland may have profited from the war, but it did not knowingly or deliberately profit from the Holocaust. Switzerland was not Auschwitz, yet these accusations make it seem as if the Swiss supported the extermination of Jews.”

Recently Hans Schaffner, head of the Swiss Federal Office of War Economy from 1939 to 1946, wrote with some asperity in The New York Times of April 6 that the recent charges against Switzerland were not based on any new information. “All the relevant details have been available since 1946,” he wrote. “But what is new is the surge of resentment against Switzerland” and, underlying it, the ignorance of Switzerland’s wartime services to the West, despite its vulnerability to German attack. On the contentious question of unclaimed deposits in Swiss banks, Schaffner noted that such accounts continued to exist, and that the records are available for inspection, adding, “Other countries, including the United States, simply took the money after a period of time and destroyed the records.” As for the talk about reopening the freely negotiated agreement of 1946, Schaffner describes this as nothing short of scandalous.

Detached observers may tend to sympathize with these views and with Isabel Vincent’s point that the more strident of Switzerland’s recent critics have had a tendency to ignore the beam in their own eyes for the mote in Switzerland’s. One does not have to condone Switzerland’s wartime behavior to recognize that other nations were also guilty of abuses similar to theirs. As Vincent writes, other neutral and nonbelligerent countries, such as Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Turkey, and Argentina, helped the Nazis launder looted gold and other assets and sold them strategically important goods. It is worth remembering, moreover, that during the war American officials, hiding behind a cloak of moral superiority as their Swiss counterparts hid behind one of neutrality,

cavalierly overlooked the suffering of millions of Jews. Although they knew about the Final Solution, they chose not to bomb railway lines leading to the death camps. Despite reports of Nazi atrocities against Jews in the Third Reich, the United States, like Switzerland, set up strict quotas on allowing Jewish refugees into the country.

And when it had a chance to work for justice after the war, the United States simply chose not to act.

It comes as no surprise to learn that recent findings in the National Archives in Washington suggest that financial institutions in the United States and Canada helped the Swiss launder Nazi gold during the war and that an inquiry is underway in Canada to determine what part the Bank of Canada may have had in such activities.

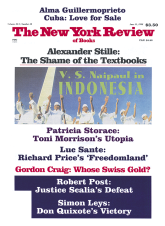

This Issue

June 11, 1998

-

1

Max Frisch, Stiller: Roman (Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp Verlag, 1963), p. 292.

↩ -

2

Gottfried Keller, Züricher Novellen: Aufsätze (Basel: Diogenes, 1978), p. 278ff.

↩ -

3

Adolf Muschg, Die Schweiz am Ende, Am Ende die Schweiz: Erinnerungen an mein Land vor 1991 (Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp Verlag, 1990), p. 173.

↩