In response to:

Giant in the Woods from the April 9, 1998 issue

To the Editors:

Set within an otherwise comprehensive, insightful, and well-balanced article on Alvar Aalto, Martin Filler’s remarks concerning Aalto’s wartime relations with fascist Germany stand out as disturbing glosses that leave erroneous impressions on the uninformed reader. The paragraph in question in Filler’s article is principally based on the chapter entitled “Finland’s Continuation War” from Goran Schildt’s book, Alvar Aalto: The Mature Years (Rizzoli), in which Schildt carefully describes the difficulty of Finland’s position vis-à-vis the Soviet Union and Germany. After quoting a letter from Maire Gullichsen sent to Aalto in July of 1941 that speaks of the hopelessness of the situation, Schildt writes, “Aalto’s loathing of Hitler and abhorrence of all Nazi propaganda were at least equal to Maire Gullichsen’s….”

Further, Mr. Filler’s comment “Aalto was all too willing to collaborate with the fascists” is a distorted and subjective abridgement of Schildt’s highly qualified “For all his antipathy to Nazism, Aalto could not avoid some collaboration with the German comrades in arms” (p. 67). The activity in question, Aalto’s trip to Germany in 1943, is carefully explained. As chairman of the Association of Finnish Architects, Aalto was expected to join a delegation from the Association that had been invited to Germany to inspect the progress of standardization (p. 67). “The hosts requested that Aalto, as the association’s chairman, head the delegation, but he found various pretexts not to go, and four other architects left for Germany without him. When the hosts sent a military plane to pick him up a week later, Aalto could no longer wriggle out of going.”

Mr. Filler’s quotations of Aalto’s remarks come directly from Schildt’s inclusion of an extensive unpublished interview of one of the participants, Esko Suhonen, in 1976 for the Finnish Society of Architects. Suhonen’s description of Aalto’s behavior is consistent with his well-known bohemian, anarchical, and antimilitaristic personality, so well described by Schildt throughout his numerous Aalto chronicles. Considering the fundamentally absurd existential context of the trip set amidst the hopeless condition of the war, Aalto’s naturally exuberant wit and grim humor don’t seem out of place, but quite human—Suhonen is quoted: “As for Alvar Aalto’s attitude: he took the trip more or less as a joke.” And further: “In any case, I want to tell you of the last function we attended at which Alvar behaved in a very…how shall I put it?…manly way, at the same time showing his unique sense of humour.”

Aalto “had stubbornly kept to his declared decision not to make any speeches during the trip” until the end when after prolonged celebrations he agreed to make the “obligatory farewell speech.” Left out of Mr. Filler’s quotations are Aalto’s initial remarks: Suhonen says that “he started by saying that we Finns are neither Nazis nor Bolsheviks.” “We are actually forest apes from the land of Eskimos, Waldaffen aus Eskimoland.”

“I do not know very much about what has been built here in the Third Reich, as because of my work in Boston I have been here so rarely. But once when I was waiting for Lawrence [sic] Rockefeller at the Harvard Club, my eyes happened to fall on a book with red covers on the shelf. I took it down, and discovered that it was written by an author completely unknown to me by the name of Adolf Hitler. I opened up the book at random, and my eyes fell on a sentence that immediately pleased me. It said that architecture is the king of the arts and music the queen. That was enough for me; I felt that I did not need to read further….”

Suhonen continues: “This brought down the house. Everyone appreciated Alvar’s speech. This is how he acted throughout the trip. In our discussions with our hosts, he kept just barely within the limits of the acceptable by always coming up with a mitigating joke at the end.” Mr. Filler’s comment “Aalto gave a speech that today seems less than a joke” itself seems grossly out of place and a misreading of the obvious.

Schildt ends his chapter with a brief story that Mr. Filler has chosen to omit. At a meeting hosted by Albert Speer, “Aalto expressed his concern about the fate of a former associate of his, the young Danish architect Nils Koppel, who had just been arrested by the Gestapo in Copenhagen. [Later] Koppel, who was Jewish, was about to be sent to a concentration camp in Germany, when he was released without explanation, evidently on Speer’s direct orders. He immediately fled to Sweden, where he soon found work as an assistant to Aalto in a Swedish architectural project.” Schildt adds in a footnote: “The author found out about Aalto’s contribution to Koppel’s release in an interview with Koppel in Copenhagen on March 13, 1986.”

The inclusion of this story, as well as the omitted contexts of Aalto’s speeches and background material in Schildt’s texts would have given a fuller, truer, and more appropriate account of Aalto’s actions, one that would have more fully complimented Mr. Filler’s otherwise excellent article, and been more faithful to the great depth of Aalto’s humanism—a trait not simply applied to architecture, but a deep force of character that imbued everything he did.

Michael Trencher

Professor, School of Architecture

Director, Alvar Aalto Study Center at Pratt

Pratt Institute

Brooklyn, New York

Martin Filler replies:

Some people find certain things funny and others do not. I for one still fail to see the humor in Alvar Aalto’s wartime trip to Nazi Germany. Aalto might indeed have been induced to pay an official visit to the Third Reich in 1943, but was he in fact compelled, at the end of what can only have been an appalling journey, to rise and pay homage to Adolf Hitler? There is irony, but no amusement, in the coincidence that the architect’s encomium was delivered at Wannsee, where, at the infamous conference just a year earlier, the mechanics of the Final Solution had been set in motion.

I do not feel that Professor Trencher’s fuller citations alter the essential truth of what Iwrote. I understand the institutional stake that he, as director of an Aalto study center, has in trying to minimize what even the architect’s most authoritative biographer characterizes as “collaboration.” And as much as I myself honor Aalto’s humanism, I must stop short of the sort of idealization Professor Trencher indulges in when he writes of the architect’s “deep force of character that imbued everything he did.” Had Aalto’s Wannsee episode occurred in 1933, his tribute, repellent though it was, might be dismissed as naive; that it happened in 1943 can only be seen as something worse. Furthermore, if Aalto could claim, as he did in his farewell speech, that by 1938 (the year of his first visit to the US) Hitler was “completely unknown to me,” then he was at best disingenuous.

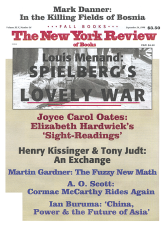

This Issue

September 24, 1998