It used to be that the best way for a Westerner, male or female, to get mentioned in the papers was to shoot up a town. A certain volume of gunplay, even if ineffective, usually brought instant celebrity, as many an entry in this big reference book attests. Wordplay, on the other hand—particularly serious wordplay—has not been as warmly welcomed. The world public has always wanted to read about the American West, but, from at least the time of Ned Buntline (Edward Z.C. Judson), its overwhelming preference has been to read the colorful if bizarre fictions that the pulp writers of many countries have so voluminously supplied.

Some readers may recall James Thurber’s amusing essay “The French Far West,” in which he discusses the French westerns he liked to relax with, in one of which a character named Wild Bird Hickok manages to liberate Pittsburgh, which was under heavy siege by les peaux-rouges. One of the more illuminating entries in this encyclopedia is the one headed “western novelists, European,” which makes clear that our home-grown pulpers, industrious though they have been (Zane Grey 78 books, Louis L’Amour 108 at last count, Max Brand—real name Frederick Schiller Faust—a life work estimated at 30 million words), are slackers compared to the Europeans. The Norwegian Rudolph Muus has written over 500 westerns, the Frenchman George Fronval more than 600; in the nineteenth century Friedrich Gerstäcker rambled through 150, H.B. Mollausen managed 178, and Karl May produced the immensely popular Winnetou novels, providing the source, in the 1960s, for an amusing series of Euro-westerns starring Lex Barker as May’s hero, Old Shatterhand.

The fact that for more than 150 years millions of readers have been willing to refresh themselves by diving eagerly and repeatedly into this Niagara of froth should give any writer or scholar proposing to write something at least nominally truthful about the West a handsome opportunity for reflection. Is a public that will happily subscribe to the sumptuous leatherette edition of the principal works of Louis L’Amour (in 120 volumes, several of which are compilations of the Master’s aphorisms, scrapbooks, and chance remarks) really likely to care about the intricacies of land-use legislation, or the struggle over water rights in the Great Basin, or the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, or indeed any of the 2,400 subjects this encyclopedia attempts to address?

The answer is no, and it’s been no since Lewis and Clark returned in triumph to St. Louis in 1806; and yet a lot of honest scholars and serious writers grit their teeth and soldier on, well aware that lies about the West—lies that are being projected every day in vivid color on a big screen somewhere—have a potency with the public that their modest truths can rarely match.

The first edition of The Reader’s Encyclopedia of the American West was published by Thomas Y. Crowell in 1977, in a smaller, considerably less stately format. Before the 1970s Western Studies—if that’s an appropriate term—had been a kind of ragbag discipline, perhaps not a discipline at all. A number of good, quirky books got written, but, on the whole, the field had a weedy look. Country editors, prairie schoolmarms, county historians, retired lawyers, lone professors here and there, and not a few raving eccentrics saved a good many records and did a certain amount of useful groundwork. There were heroes among them, not all of whom get due mention in this book. George E. Hyde of Omaha, totally deaf and almost blind, working only with the resources of the Omaha Public Library and what it could get him, wrote his three excellent books about the Sioux,* saving segments of tribal history that the Sioux themselves would have lost. Beyond the Hundredth Meridian, Wallace Stegner’s splendid book on John Wesley Powell, appeared at a time (1954) when not one citizen in ten thousand would have recognized Powell’s name, though when he emerged from his pioneering exploration of the Grand Canyon of the Colorado in 1869 he was for a time something of a folk hero and later became an intellectual hero too, because he saw clearly that successful westward expansion into the arid lands would depend on careful management of limited water resources. Walter Prescott Webb published his pioneering study The Great Plains in 1931, when no one but himself would have supposed there was anything worth studying about a lot of flat empty grassland. And a Montana newspaperwoman named Helena Huntington Smith managed to corner the old cowboy Teddy Blue Abbott and help him produce the best of all cowboy autobiographies, We Pointed Them North (1939).

What was lacking until the 1970s in regard to the American West was something like what the Annales school achieved in France: the kind of critical mass that results when a number of trained intellects are working in full awareness of one another, though of course not in total agreement.

Advertisement

By the 1970s the American Studies program at Yale and a number of similar programs elsewhere had begun to produce nestfuls of doctoral candidates, all hungry for subjects—and there stretched the West, as inviting to scholarship as it had once been to other, more arduous forms of exploration. In 1967, a decade before the first edition of this encyclopedia appeared, the Yale-trained historian William H. Goetzmann won the history Pulitzer for his impressive book Exploration and Empire; from then on the West could be seen to have a certain shine in academic circles. By the mid-1970s, a century after the great sky-darkening swarms of grasshoppers flew down and ate up Kansas, another hungry swarm appeared from the general direction of New Haven, this one composed of would-be Ph.D.s, as eager to strip the West of thesis topics as the grasshoppers had been to strip it of grain.

This surge of scholarly interest was anticipated at the popular level by Time-Life, which quickly rolled out a twenty-volume series called The Old West, each volume being devoted to a given trade (Rivermen, Cowboys, Trail-blazers, Chiefs, Gunfighters, even Canadians!). This series is crammed with pictures, as one might expect, accompanied by texts that vary from not bad to bad; I confess that the majesty of the whole enterprise was diminished for me by the fact that, on the shelf, the set looks a lot like the aforementioned principal works of Louis L’Amour.

By the 1980s the revisionist historians were in full cry, challenging—usually sensibly and often passionately—the long-prevailing triumphalist view of the winning of the West, which was that winning it was a mighty good thing; a dirty job, of course, in some respects, but one that had to be done if we were to fulfill our commitment to Manifest Destiny. On the contrary, cried Patricia Nelson Limerick, Clyde A. Milner II, Charles Rankin, Donald Worster, and a score or so of their colleagues and sympathizers: it was a job, they argued, that had devastated the environment, ruined much of the land, destroyed the native peoples, penalized minorities, wreaked fiscal havoc, and, last but not least, did in tens of thousands of the would-be winners themselves, many of whom won nothing but narrow graves, often within only a hundred miles or so of where the Gateway Arch now stands.

The editor of The New Encyclopedia, Howard R. Lamar, well aware that the long, hot debate between revisionists and triumphalists has left a number of sensibilities rather severely scorched, has established something like an equal-time policy for this new edition. If an entry states a revisionist position the contributor is obliged to at least sketch in the position that he or she is in disagreement with.

This is certainly courtly of Professor Lamar, but I’m not sure who he thinks he’s fooling. A glance at the contributor’s list—fifty contributors are either from or at Yale—makes it clear that revisionists are solidly in command, and since scholars with revisionist leanings have been pouring out of the graduate schools for twenty-five years it would be odd if it were otherwise. The major histories and reference books to appear in the Nineties, including this one, are rife with revisionist overlappings. Richard White, who himself wrote the whole of ‘It’s Your Misfortune and None of My Own’: A New History of the American West (Oklahoma University Press, 1993), contributes to The New Encyclopedia and to the recent Oxford History of the American West (1994) as well. Two of the editors of the Oxford History, Clyde A. Milner II and Martha A. Sandweiss, also contribute to The New Encyclopedia, several of whose contributors are to be found in the Oxford book—all of which probably only goes to show that the rich get richer. The only recent work of reference not clearly in the revisionist camp is Dan L. Thrapp’s three-volume Encyclopedia of Frontier Biography (1989), which could have benefited from a little more revisionist vigor.

Despite its editor’s polite ground rules The New Encyclopedia doesn’t entirely avoid revisionist overkill. Why, for example, must the poor old Turner (or Frontier) Thesis, long since battered to its knees, be further pummeled by entries demonstrating that it doesn’t hold for Australia or Canada either? Its author, the historian Frederick Jackson Turner, argued, at the end of the last century, that our institutions, our social systems, and perhaps our character had been shaped by an open frontier and the availability of an abundance of land, either cheap or free. Perhaps when these entries were first published, in the 1977 edition, it was not yet evident that the Frontier Thesis was down for the count, so Canada and Australia got piled on, just in case.

Advertisement

As in any big reference book, odd facts burble up. I was not too surprised to discover that old Madame Chouteau, matriarch of the founding family of St. Louis, had been the first person west of the Mississippi to keep honeybees, but it was a shock to discover that as many as 50,000 cattle may have perished in Maryland, in the harsh winter of 1694-1695. In Maryland? Given that the first cattle only arrived on the Eastern Seaboard in 1611, that would suggest some vigorous breeding stock, besides causing one to wonder what a seventeenth-century Maryland cowboy would have looked like.

The focus on Native American life is both sharper and more extended in this new edition. An entry for Acoma pueblo—one of the oldest continuously inhabited communities on the North American continent—is on the first page, and a discussion of the Zuni people is on the last. Policy, legislation, urban history, the environment, industrial history, and military matters are all done well. Writers are done poorly, so poorly, indeed, that one wonders whether the editor wouldn’t have been better off adopting the old method, in which tiny photographs of ten or twelve writers were squeezed onto a page, allowing the reader to choose on the basis of looks.

In a remarkable and perhaps unconscious obeisance to popular taste it is the gunfighters who are done best of all, in crisp essays written with energy and finesse, and an attention to detail that exceeds what one gets for presidents, Indian chiefs, or anyone else. We learn, for example, that it was Jim Younger’s “jaw” that was shot away in the Northfield, Minnesota, raid, and that Jesse James was standing on a chair straightening a picture when the assassin Robert Ford shot him down. The major shootists—the Earps, Doc Holliday, John Wesley Hardin, Hickok, Billy the Kid—get thorough and leisurely reconsiderations, in entries free of the boilerplate that is apt to be laid on for territorial governors or railroad magnates. The tug of the dime novel seems to extend even to the groves of Ivy.

The New Encyclopedia is an informative and useful book, but it’s possible to read every word of it without acquiring a very clear sense of where, exactly, the contributors think the American West is. In part this vagueness is natural, since historically there have been several Wests. Once—as many entries acknowledge—the West began at the Atlantic beaches. By the time of Daniel Boone (1734-1820) it had moved beyond the Cumberland Gap. To Lewis and Clark it was the trans-Mississippi, though later explorers seemed to feel they weren’t really in the West until they crossed the 100th Meridian. It’s been nowhere clearly stated that when we talk about the West we may be talking about three entities at once: the historical West, the geographic West, and the psychological West, or what one might call the West-in-the-mind’s-eye. These three Wests are interwoven in pat-terns that are confusing and indistinct, though the Goetzmanns, William H. and William N., came close to achieving a conscious synthesis of the three entities in their book The West of the Imagination, a study of Western art and its reception in the East that had first been a PBS series. No matter how hard historians try to focus on the historic West or the geographic West, the West-in-the-mind’s-eye subtly but almost invariably intrudes.

For this we have the camera to thank. As soon as images became easily reproduced, and thus movable, certain cities, countries, regions became, for export purposes, reduced to one building, landmark, symbol: for China the Great Wall, for Egypt the Pyramids, for London Big Ben, for Paris the Eiffel Tower, for Moscow the Kremlin, and for the American West Monument Valley. John Ford, by setting several of his best westerns in Monument Valley—even though the stories they were telling were supposedly occurring in Texas, Arizona, or elsewhere—simply made Monument Valley stand for the West, a position since adopted by the makers of Jeep commercials and hundreds of others needing a particularly compelling site. John Ford knew quite well that, far from being representative of the West, Monument Valley, in northern Arizona and southern Utah, was unique, not only in the West but in the world. Nowhere else are such noble buttes spaced so grandly across a red desert. But Ford insisted that the Valley was as much west as was necessary, at least for what he liked to call his “pictures,” and he got his way to such an extent that Monument Valley is now, for many millions, what they think of when they think about the West.

Virtually from the time cameras became portable, good photographers—Hillers, Jackson, O’Sullivan—began to work in the West, drawn by the skies, the space, and the extraordinary light. These photographers, like the many who followed them, were naturally attracted to the places of spectacular beauty: Yosemite, Yellowstone, the Canyon de Chelly, the Grand Canyon. The public, looking at these pictures year after year, became accustomed to seeing beauty shots, the glorious rather than the workaday West. When Richard Avedon published his stark In the American West (1985) he was greeted with howls of indignation. Where were the beauty shots? Where was Monument Valley?

Most of us, without particularly meaning to, have by now accumulated—from commercials, from ads in magazines, from picture books, from movies—a mental archive of images of the West, a personal West-in-the-mind’s-eye in which we see an eternal pastoral, very beautiful but usually unpeopled, except for the Marlboro Man. These potent images, pelting us decade after decade, finally implant notions about how the West is that are as unrealistic as those of the dime novelists.

If, on the other hand, we go to photography for information, rather than fantasy, we can learn a great deal about what life was like for people who actually lived in the West, for whom those great spaces were usually just isolating and that fine light often just brutal. The photographic resources for the study of Western life are very rich but also very disordered. I habitually page through all the new reference books just to see if any new pictures have turned up—and they do. In Richard White’s New History there is a photograph of Red Cloud’s bedroom, which contained a madonna, four American flags, and a bow. I had long wondered what the great Panhandle cattleman Charles Goodnight’s first wife looked like—Mary Ann Goodnight, the woman who followed him into the wilderness. She is not pictured in any of the many books that mention Goodnight, but, suddenly, there she is, smack in the middle of one of the Time-Life books, looking like a woman who could very well hold her own with Big Charlie. More than a century has now passed since the closing of the frontier, but the attics and scrapbooks of America are still yielding up treasures. I myself recently turned up several new images of Geronimo, on glass-plate negatives that had been used to insulate a house in Henrietta, Texas, a small town not far from Fort Sill, where he was held. From such caprice knowledge slowly accumulates; details, little by little, get filled in.

Perhaps the last person who could confidently review a full-grown encyclopedia was C.K. Ogden, who, in 1925, took up the latest Britannica and found it wanting. The New Encyclopedia could, more modestly and just as accurately, have been called a “Handbook” or possibly a “Companion,” sparing those who review it the embarrassment of having to pretend to be know-it-alls. Encyclopedias are perhaps by their nature uneven and always make tempting targets, as Diderot found out to his annoyance. Reviewing such works becomes, usually, a matter of crochets, hobbyhorses, prejudices; the editors always seem to omit the one thing the reviewer actually knows something about.

I would have liked to see an entry for aridity, which is, after all, the single most important climatic factor in most of the West; though mentioned time and again it could have earned an entry of its own, and the same goes for erosion, without which we wouldn’t have had the Grand Canyon, Monument Valley, or many another emblematic sight. I’m glad to see the Creek artist Woodrow Crombo get his due but feel it’s a pity that Korczak Ziolkowski and his dedicated family, now at about the midpoint of their effort to turn a mountain in South Dakota into a monument to Crazy Horse, had to be squeezed into two sentences in the entry for the Black Hills. When the Crazy Horse Monument is finished, sometime toward the middle of the next century, it will be the largest sculpture on earth, and it is, already, a work of extraordinary power. A bit more of a hurrah for the Ziolkowskis wouldn’t have been amiss.

The mini-bibliographies, though nec-essarily brief, seem unnecessarily tilted toward the monographic as opposed to the literary. Stegner’s Beyond the Hundredth Meridian is not in the bibliography for John Wesley Powell, Evan S. Connell Jr.’s brilliant Son of the Morning Star not mentioned under either Custer or the Little Bighorn, and Robert Caro not mentioned under Lyndon Johnson.

In 1989, just before all these new works on the West began to appear, the University of North Carolina came forth with a massive book called The Encyclopedia of Southern Culture—massive and impressively thorough. There is an entry for grits, an entry for chitterlings (or chitlins), an entry for the mint julep, and such comprehensive coverage of violence that it has to be discussed under more than thirty headings.

Should there be another edition of The New Encyclopedia of the American West I hope the Westerners in New Haven take a few tips from their cousins in Chapel Hill. For the letter C alone I can suggest two additions, the first being chili. In this increasingly secular age, what to put in chili—or what to exclude—provokes the nearest thing to religious argument to be heard in the modern West. While the great chili cookout held annually in Terlingua, Texas, is a loose equivalent of the Council of Nicea, in which many heresies are defined and many schismatics cast out.

I would also propose an entry for car wrecks, fatal. Though car wrecks happen everywhere, in the West death on the highway is as much a part of the culture as rodeos. Among writers they’ve carried off Walter Prescott Webb, Wallace Stegner, and Nathanael West; to car wrecks the movies have lost James Dean, Tom Mix, F.W. Murnau, Jayne Mansfield, and Sam Kinison. A little study would reveal many others, including Chato, the Chiricahua leader who helped General Crook find Geronimo, killed in a bad smash-up in New Mexico, in 1934.

Meanwhile there is still the West that was—with its achievement and its destruction—and the land that is, emptier and emptier on the plains, more and more weighed down with population on the Gulf and west coasts, and, always, that other, endlessly imagined West, the West that can never be fully believed or wholly denied, where Wild Bird liberates Pittsburgh, where les peaux-rouges still bite the dust of Monument Valley, where buttes are tall and horizons long, where women mainly try to stay out of the way, and where an unforgettable company, Gene and Roy, Butch and Sundance, Clint and the Duke, wild bunches galore, and a masked man who kills the bad guys with silver bullets, still gallop from commercial to commercial on some screen somewhere, every day. That’s the West that even the most accurate scholarship can’t do a thing about.

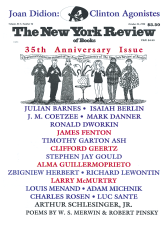

This Issue

October 22, 1998

-

*

Red Cloud’s Folk (1937), A Sioux Chronicle (1956), Spotted Tail’s Folk (1961).

↩