The power to impeach a president is a constitutional nuclear weapon and it should be used only in the gravest emergencies. It gives politicians the means to shatter the most fundamental principles of our constitutional structure, and we now know how easily that terrible power can be abused. A partisan group in the House, on a party-line vote, can annihilate the separation of powers and send a lawfully elected president of the opposite party to a drawn-out, humiliating, televised trial, a trial that would frighten markets, usurp the scarce resource of national attention for months, and damage presidential leadership and policies for even longer. Such a group can even, if it dominates the Senate as well, remove a president from office in spite of the fact that he is the only official in the nation who has been elected by all the people, and even if he still enjoys extensive support.

Nothing—nothing—can stop a party of politicians with enough votes and that ambition. They can, as Gerald Ford warned, declare anything they want a “high crime or misdemeanor.” They can ignore, as the House has ignored, the most fundamental provisions of due process and fair procedure. No court can review their proceedings, their declaration, or their verdict. No public outcry can stay their hand. Nothing can stop them but their own constitutional conscience: their own respect not just for the Constitution’s detailed text but for its deeper structure and philosophy.

The Republican House leadership claims that it has had that respect: it says that it has acted not with glee but out of a solemn sense of responsibility. We must examine that claim with the greatest care. They say that the President must not be above the law, that he must be treated like any other citizen. But the way to treat him like any other citizen is not to impeach him: in two years Bill Clinton will be a private citizen, and he can be prosecuted, by Kenneth Starr or any other appropriate officer, for anything, in a court of law where he will have the same rights of a criminal defendant that any other citizen has.

The leadership says that the President is guilty of the “high crimes and misdemeanors” that the Constitution requires for impeachment. What does that obscure phrase mean? The Founding Fathers thought that it meant a crime against the Constitution or the state: a president acting beyond his rightful authority or otherwise betraying the public trust. They repeatedly gave the example of a president who is in the pay of a foreign power. Even if we put history aside, and try to interpret the obscure phrase so that it makes good sense within the Constitution’s structure as a whole, we reach the same conclusion.

Trying a president, let alone removing him, is a seismic shock to the separation of powers that is the Constitution’s spine. When is that shock necessary—when is it not good enough to wait until the president’s term has ended? The answer seems obvious. It is not good enough to wait only when there is a constitutional or public danger in leaving a president in office, only when he has subverted public force or funds to illegal use, for example, or hounded political enemies with illegal acts, or taken a bribe, as the founders feared, or sent soldiers to war for personal gain.

Presidents may do many bad things that do not make them constitutional threats. They may turn out to be morally disappointing, not people we would want our children to copy. They may cheat on their income tax, which is very far from a trivial crime, or they may lie under oath, which is very bad but often no worse. These flaws can wait for history; those crimes can wait for judgment when a president leaves office.

True, an official who has committed heinous private crimes, like murder, reveals such inherent wickedness, and such contempt for human life, that it is dangerous to allow him to continue to exercise his powers, which include, for example, the power to send soldiers into war. But a congressman who thinks that lying to hide a sexual embarrassment, even under oath, is on the same moral scale as murder—that it shows comparable wickedness or depravity—has no moral capacity himself, and is a more dangerous threat to the nation than a president who lies, even under oath, to keep his sex life to himself.

So anyone with a constitutional conscience would shrink from impeaching President Clinton on the record the Judiciary Committee has compiled, and we must count the Republican leadership’s claim of a sad duty to impeach as either hypocrisy or constitutional blindness. The position of the so-called Republican “moderates,” who say they will vote for impeachment but would not do so if the President had confessed to a crime, is no less bizarre. Impeachment, which judges whether it is dangerous to leave a president in office, is not an occasion for a plea-bargain. If lying about sex under oath is an impeachable offense, then no amount of confessing would make it less so; if it is not, then no amount of stubbornness makes it one.

Advertisement

John Conyers said, at a particularly absurd and exasperating point in the House hearings, that he was beginning to smell a coup. In the familiar sense of that word, he was wrong, of course. But it is a kind of coup to use constitutional formulae to subvert constitutional principles: if any acts in this sad story are high constitutional crimes, it is the acts of those politicians who hate the President and his policies enough to push the Constitution out of the way when they see a chance to humiliate and weaken him.

Nothing in the long, sad story is so revealing of that partisan fury as the initial and reflexive accusation by Trent Lott, the Senate majority leader, and other members of the Republican congressional leadership that the President’s decision to bomb Iraq was a ploy designed to delay the impeachment process. Bombing may or may not have been the right response to the inspection commission’s report of Saddam’s latest noncompliance. But if it was—and few in Congress deny that it was—then the case seems strong that it was better to begin bombing at once, before any new Iraqi evasive action or diplomatic maneuver, and in the short window of time before the holy Ramadan month began, than to wait until that month had ended.

In any case, however, it is grotesque to suggest that the timing of a delicate military action should wait upon Congress’s impeachment schedule rather than the other way around. A Senate trial cannot begin until next year anyway, and nothing can explain the leadership’s inevitably damaging accusation, made when American pilots are at risk and when the reaction of other nations to the American strike is both uncertain and crucial, except a petulant anger that their vengeance will be delayed—or, perhaps, a chilling fear that the decision will somehow be postponed to the next House, which was elected last November and will therefore be more representative of the public’s choice, but in which the Republicans will have five fewer votes.

Suppose they succeed in impeaching the President, sooner or later. The greatest damage may be the lasting damage: whatever happens in the Senate, the precedent they will have created will be both a terror and a temptation for a long time to come. We must do what we can to hasten the day when that precedent is unanimously denounced as a mistake not to be repeated. We must cultivate a long memory. Most of those who vote for impeachment will run for office again in two years, and we must encourage and support opponents who denounce them for what they have done, in any way we can, including financially. The zealots will have stained the Constitution, and we must do everything in our power to make the shame theirs and not the nation’s.

—December 17, 1998

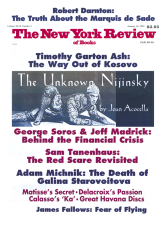

This Issue

January 14, 1999