To the Editors:

Since the end of the cold war, it is remarkable how quickly the archives of the vanquished have been introduced as incontrovertible evidence that the so-called “revisionist” critics of that conflict had it all wrong. In his January 14 review, Sam Tanenhaus refers to “the revisionist view put forward in the 1960s…” and boldly asserts that this school of cold war historiography has been “discredited by archival records in Moscow.” Mr. Tanenhaus offers this sweeping opinion in an offhand manner, as if to suggest that the argument is closed.

The argument about the history of the cold war is more complicated and nuanced than can be neatly divided between revisionist and orthodox paradigms. It is this complexity that Mr. Tanenhaus misses with his easy dismissal of the revisionists. If anything, it can be argued that much of the very incomplete evidence from the “enemy archives” vindicates the notion that American policymakers at times rashly and needlessly overmilitarized a conflict with an ideological enemy they knew to be economically and militarily inferior. (See, for instance, Melvyn P. Leffler’s essay, “Inside Enemy Archives: The Cold War Re-opened,”in Foreign Affairs, July/August 1996.)

While any such generalization must be regarded as tentative, the Moscow archives are also making it undeniably clear that the Soviet bloc was less monolithic than the defenders of Cold War orthodoxy claimed. Indeed, numerous countries or leaders frequently regarded in the West as nothing more than Kremlin puppets turn out to have had their own agendas which often diverged from or even clashed with Moscow’s. This fact underscores the importance of “national communism” and raises doubts about NSC-68, the “domino theory,” and other US strategies based (or at least publicly justified) on the assumption of a Soviet “master plan” for “world domination” in which other countries blindly fulfilled their anointed role.

By pointing out the provisional nature of the findings from the Communist world’s archives, we do not mean to deny or minimize the relevance or importance of new evidence regarding such well-known atrocities as the Stalinist purges and gulag, Mao’s disastrous “Great Leap Forward,” or the imposition of Kremlin-imposed dictatorships on the nations of Central and Eastern Europe after World War II.

At the same time, nothing has emerged from these archives to exculpate US misconduct in Iran, Guatemala, Vietnam, Cuba, Nicaragua, and elsewhere, or to settle broader debates over responsibility for the division of Germany or Europe, the duration of the cold war, the length, intensity, and dangers of the nuclear arms race, the causes of the Soviet collapse, and many other issues. As most researchers in the Communist world’s activities will readily acknowledge, the new findings have often been fascinating, illuminating, and provocative, and have indeed cleared up some specific mysteries and controversies, but it will require decades of intensive research, careful analysis, and integration with US and other sources, before historians can legitimately cite them as establishing any sweeping new interpretations of cold war history.

In the meantime, the punditocracy should refrain from seizing upon a few sensational revelations from the Communist archives to advance a triumphalist historiography.

Gar Alperovitz, Eric Alterman,Barton J. Bernstein, Kai Bird, H.W.

Brands, Robert Buzzanco, Bruce Cumings, Carolyn Eisenberg, Walter LaFeber, Lloyd C. Gardner, James Hershberg, Michael J. Hogan, Warren F. Kimball, Anna Nelson,John Prados, Marcus Raskin,Martin Sherwin, Anders Stephanson, Marilyn B. Young

Sam Tanenhaus replies:

Nineteen academicians and journalists have united to condemn the “sweeping opinion” of something they call “the punditocracy.” More specifically, they have trained their fire on two sentence fragments, totaling fourteen words, in a review of mine that runs to some seven thousand. My passing reference to cold war revisionism is said by the signatories to “advance a triumphalist historiography” and to promote a spurious division “between revisionist and orthodox paradigms” when a “more complicated and nuanced” perspective is called for.

But they neglect to explain what I got wrong. My essay mentions cold war revisionism in only one context: a brief discussion of how the post-Yalta superpower conflict is treated in the book I was reviewing, Ellen Schrecker’s Many Are the Crimes. I noted that in common with many revisionists Schrecker “tilts the balance of blame heavily toward the United States” and argues that Stalin’s goal in the immediate aftermath of World War II was simply to “ensure [Soviet] security.” If the USSR’s actions were purely defensive, I wrote, then why did they “require the imposition of puppet regimes and the crushing of all dissenters”? Do the signatories dispute this point or my observation that the archival record contradicts Schrecker? Apparently not, since they acknowledge “the relevance [and] importance of new evidence regarding…the imposition of Kremlin-imposed dictatorships on the nations of Central and Eastern Europe after World War II.”

What, then, are the signatories exercised about? Something very different, it would appear. They denounce “US misconduct in Iran, Guatemala, Vietnam, Cuba, Nicaragua, and elsewhere,” and caution that debates remain unsettled on such questions as assigning responsibility for “the division of Germany or Europe, the duration of the cold war, the length, intensity, and dangers of the nuclear arms race,” and more. In other words, they don’t want to give a clean bill to the architects of US foreign policy during the cold war. But where have I tried to do that? Certainly not in my New York Review essay, which does not touch, even glancingly, on that topic. Nor was there any reason it should have done so. My subject and Ellen Schrecker’s was the interplay of domestic communism and anticommunism in the period leading up to and including the first decade of the cold war. The book does not deal with the questions the letter raises, and neither does my review. The signatories’ quarrel is not with me but with the formulators and defenders of US foreign policy.

Advertisement

Thus they assert that “American policymakers at times rashly and needlessly overmilitarized a conflict with an ideological enemy they knew to be economically and militarily inferior,” and that “the Soviet bloc was less monolithic than the defenders of cold war orthodoxy claimed.” Again, these issues lie outside the purview of my essay, though this did not stop the signatories, despite their plea for “nuance” and complication and the careful weighing of evidence, from erroneously ascribing “triumphalist” opinions to me. I suggest these experts examine my recent review of Daniel Patrick Moynihan’s new book, Secrecy, in which I remarked that by 1973, “Misreading the Soviet Union had become de rigueur for policy experts. American analysts diligently ignored the truth about our rival superpower: its dysfunctional economy, its political system rotten with corruption, its republics seething with ethnic hatreds, its satellite countries in rebellion. Our leaders insistently portrayed this shambles of an empire as an indestructible colossus. When the truth overtook us in 1989, the custodians of the free world were suddenly clueless” (The New York Times Book Review, October 4, 1998). Are those the words of a “triumphalist”?

Apart from objecting to the fourteen words they quote, the signatories do not challenge any conclusions reached in my review. Can it be that this brave herd of independent minds joins me in rejecting the apologetics of Ellen Schrecker and in accepting the latest evidence on such long-standing controversies as the infiltration of the federal government by American Communists, the guilt of Alger Hiss and the Rosenbergs, and the damage done to the American left by the CPUSA? If so, then the gulf dividing revisionist and “orthodox” historians has narrowed sharply, and this strange letter stands as a testament to that fact.

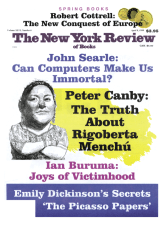

This Issue

April 8, 1999