Salman Rushdie’s novel The Ground Beneath Her Feet is to be “supported,” we hear, by a new release from the rock band U2. As if in coy echo, the promotional blurb to Vikram Seth’s An Equal Music tells us that “bookstores have invited string quartets to perform during his readings.” Simultaneously? While the phenomenon of celebrity publishing has accustomed us to the idea that the book itself may be the least exciting part of an overall package, it is disturbing to find two authors with such literary ambitions allowing our eyes, or indeed ears, to be distracted from the pleasures of the text. The multimedia experience may be fashionable, but in literature distinction and discrimination are of the essence. One reads, for preference, in a quiet place.

There are uncanny parallels between Rushdie’s and Seth’s latest efforts. Like chalk and cheese it seems impossible not to mention them together. Both books are by hugely successful, male, Anglophone, Indian-born authors now in early middle age. Both feature musicians as their central characters. In each case those protagonists are involved in a love triangle. In each novel the musician-lovers lose sight of each other for ten years, allowing a third party, this time a non-musician, to slip in. Both first-person narrators seem driven to tell their stories out of a sense of loss, the need to overcome pain and disillusionment. Much, very much, is made of the intimacy generated by the lovers’ creating music together and in both cases the music played comes to be seen as a manifestation of a transcendental realm of feeling. But while Rushdie with his usual spirited bluster seemed set on giving back to the world only the cacophony the mind is in any event subject to these days, Seth is after more calculated and harmonious effects. The distance between the rock band in Central Park pushing amplification to the limits to drown out helicopters and sirens and the tail-coated string quartet entertaining a scrupulously silent, if somewhat dusty, middle-class audience beneath a baroque ceiling rose will serve well enough as an analogy for the distance between these two performances.

Vikram Seth’s reputation began with The Golden Gate. Here some light-hearted satire and a series of sentimental relationships were rescued from banality by being presented entirely in tightly rhyming tetrameter. The effect, at least in the opening cantos, is absolutely charming. Unlike Rushdie, when Seth approaches his readers, it is always to seduce, never to accuse, even less to browbeat. But he is careful not to challenge either. Despite its frequent lapses into doggerel The Golden Gate slips down like a pleasant ice cream. It would be churlish to raise objections and simply unkind to hazard comparison either with Pushkin, whom Seth names as his model, or Byron, of whom the reader, despite the different verse form, may more often be wistfully reminded. Even returning to the book today, one cannot help but take one’s hat off to someone who had the resources and tenacity to bring such a project to a conclusion and convince a publisher it would work.

That hat-doffing admiration—the critical faculty forestalled by wonder—is something Seth once again sought and largely attained with his second work of fiction, A Suitable Boy. Much was made at the time of its publication of the distance the author had trav-eled from The Golden Gate, from a good-humored satire of contemporary California in chiming verse to this vast, meticulously researched drama of India in the 1950s, the crimes and loves of four extended families in over 1,300 pages. But with hindsight the similarities between the two ventures are evident enough: first the decision to ignore current experimental trends in literary fiction, particularly Anglo-Indian fiction, in this case by resorting to a conventional narrative prose that offered a tried and tested vehicle for pleasure; then the gently satirical delight in social trivia with here the exoticism of the mainly Hindu milieu standing in for the wit of clever rhyme, and the sheer scale and intricate extension of the plot serving to generate that same gasp of disarmed surprise.

There was a similar concentration, too, on affairs of the heart, again with an awareness of the dangers of passion and the virtues of traditional, in this case even dynastic, common sense. Unpleasantness and indeed horror are not excluded, but as Anita Desai acutely remarked in these pages,1 Seth tends to hurry over the brutal and lurid as if such things were really too distasteful to occupy much space on his charming pages.

Since a great deal of contemporary fiction seeks primarily and often solely to shock, this is a decision that will hardly raise hackles. If a problem does arise it is when we begin to feel that Seth’s designs upon us are all too irksomely evident. There are readers whose antennae go up before succumbing to seduction. Various Indian critics in particular suggested that A Suitable Boy’s complacent vision of Indian society verged on the grotesque. The desire to please must always be in complex negotiation with the spirit of truth. In this sense the decision, in An Equal Music, to encourage us to look unhappiness long and hard in the eye might be seen as an attempt on Seth’s part to redress the balance.

Advertisement

The narrator, Michael Holme, describes himself as “irreparably imprinted with the die of someone else’s being.” Unable, that is, in his mid-thirties, to get over his first love of ten years before, he lives in “a numbed state of self preservation,” in a tiny attic apartment to the north of Kensington Gardens, eking out a barely adequate living playing second violin in a string quartet and teaching a variety of unsatisfactory students, with one of whom he pursues an affair that offers no more than physiological relief. The book’s three brief opening paragraphs, which also form a separate section of their own, strike a melancholy and decidedly minor chord that is to be sustained, with variations, throughout.

The branches are bare, the sky tonight a milky violet. It is not quiet here, but it is peaceful. The wind ruffles the black water towards me.

There is no one about. The birds are still. The traffic slashes through Hyde Park. It comes to my ears as white noise.

I test the bench but do not sit down. As yesterday, as the day before, I stand until I have lost my thoughts. I look at the water of the Serpentine.

Immediately we recognize the familiar sadness of the lonely man in the urban scene, trapped in empty repetition, eager to forget, clearly attracted to and menaced by that black water the wind blows at him. There is nothing remarkable here. We might even want to call it creditably low-key. Gone the springy step of The Golden Gate, gone the sprawling exoticism of A Suitable Boy, the style now spare, often willfully limp, Seth thus renounces the visiting card of virtuosity. When we discover that his hero is not only white and English but that he hales from the town of Rochdale, a declining industrial satellite on the edge of the Manchester conurbation, the kind of place that tends to be the butt of dismissive jokes in the sophisticated south, it becomes clear that if there is to be a gasp of surprise this time around, it must be at Seth’s boldness in placing himself right in the mainstream of English fiction, doing exactly what the English do.

Michael, then, is marooned in the past, “with inane fidelity fixated on someone who could have utterly changed.” Ten years ago, studying in Vienna, he fell in love with another student, Julia, a pianist. For a year things went well, but Michael’s music teacher was a harsh master and dissatisfied with his achievements. Despite Julia’s insistence that he see the experience through, Michael gave up, leaving both girlfriend and the possibility of a solo career behind. When, two months later, he began to write to her, she did not reply.

The exact dynamics of this break-up, the reasons for Julia’s not replying to Michael’s letters, for his not simply returning to see her, are never clear to the characters themselves and even less so to the reader. What evidently matters to Seth, however, is that it should appear an unnecessary separation in a relationship of enormous potential. Michael is thus more understandably in thrall to his sense of what might have been. To make matters worse, since he and Julia used to play together in a trio, his very vocation constantly brings him up against the memory of her. In particular there is a Beethoven trio—opus 1 number 3—that he often listens to but cannot play either privately or professionally. Informed, significantly enough by Virginie, his student who is also his current girlfriend, that Beethoven in later life prepared a now obscure variation of this early work as a quintet, Michael becomes obsessed with tracking the piece down and getting his quartet to perform it with the help of an extra player. It will both remind him of Julia but at the same time be different from the past. “I know,” he thinks excitedly, “that, unlike with the trio, nothing will seize me up or paralyse my heart and arm.”

Instead, then, of seeking a more appropriate sentimental variation with Virginie, Michael sets out to find this different and improbable version of what he remembers all too well. We are thus treated to one of those episodes, now so familiar in contemporary fiction, where someone searches for the crucial but elusive text in specialist libraries and secondhand shops, only to meet with the predictable mixture of obnoxious obtuseness and unhelpful helpfulness. Ironically, it is precisely as, at last successful, he boards a bus to bring home an old vinyl recording of the piece, “so desperately sought, so astonishingly found,” precisely as he prepares a decidedly sentimental, indeed potentially masturbatory (not a word Seth would use) evening with this variation (“I’ll come home, light a candle, lie down on my duvet and sink into the quintet”), that the lovelorn Michael sees, after ten years, who but Julia herself going by on a bus in the opposite direction. The variation, we immediately understand, is to be with the loved one in person. When his quartet does play with an outside artist, it will be with Julia.

Advertisement

But before we consider how Seth tackles the revival of lost love, let’s turn aside for a moment to look at his handling of Michael’s provincial boyhood, since this strand of the narrative offers in miniature an example of the writer’s aesthetic at work.

Home of the industrial revolution, the north of England has a long and spirited tradition in socially engaged fiction. From Gaskell’s Mary Barton to the novels of contemporary writers like Pat Barker and Jane Rogers, first the ascendancy of the brutal factory owner, then the desolation of industrial decline, and, throughout it all, the plight of the poor have all been passionately documented. Seth is aware of this of course and as the dutiful Michael goes to visit his aging father at Christmas, he offers us a number of pages in line with the tradition, portraying a disadvantaged boyhood in a decaying landscape.

The handsome town hall presides over a waste—it is a town with its heart torn out. Everything speaks of its decline. Over the course of a century, as its industries decayed, it lost its work and its wealth. Then came the planning blight: the replacement of human slums by inhuman ones, the marooning of churches in traffic islands, the building of precincts where once there were shops. Finally two decades of garrotting from the government in London, and everything civic or social was choked of funds: schools, libraries, hospitals, transport. The town which had been the home of the co-operative movement lost its sense of community.

The only other outsider I can think of who took on industrial England was the Australian Christina Stead in Cotter’s England.2 With fantastic energy, mimetic resources, and reforming zeal, Stead achieved the astonishing feat of giving us a believable British working class, chattering, suffering, living, laughing, loving, and—she never forgets—hating as hard as could be. This is not Seth’s project. He does not risk the local dialect. Aside from these few pages, his hero shows no interest in politics or the condition of England. Nor any more does Seth. Why then bother with this reductive and potentially platitudinous picture of the north? Is it necessary for authenticity?

Certainly Seth works hard to intertwine the history of the town with that of Michael’s family, mainly in order to present the latter as victims. His father’s butcher shop was appropriated to make way for a road which was never built. Bereft of his profession, the father fell ill. Nursing him, the mother suffered a fatal stroke. Over Christmas Michael plans “to lay a white rose” on the parking lot that eventually replaced the shop and family home: “the flat and, I hope, snow-covered site of my mother’s life.”

Political and again poignant considerations also come into the account of Michael’s early education on the violin:

Because the comprehensive [school] I went to had been the old grammar school, it had a fine tradition of music. And the services of what were known as peripatetic music teachers were provided by the local education authorities. But all this has been cut back now, if it has not completely disappeared. There was a system for loaning instruments free or almost free of charge to those who could not afford them—all scrapped with the education cuts as the budgetary hatchet struck again and again…. If I had been born in Rochdale five years later, I don’t see how I—coming from the background I did, and there were so many who were much poorer—could have kept my love of the violin alive.

Cursory research is being made to work very hard here. Michael expresses commonplace views frequently fielded in the Letters to the Editor section of British newspapers. But to respond with the standard objection that in the same period the people of Lancashire have equipped themselves with cars, TVs, and computers, that the consumption of beer, cigarettes, and junk food could never be described as negligible, that though one would always applaud a government that provided violins to its people, the people themselves are hardly screaming for them—to raise this objection would simply be to miss the point.

Seth doesn’t want to get us interested in the politics or economics of the situation. He himself is not at all interested in the question of how the north of England (where I was born and spent my infancy, and sang indifferently in a marvelous choir) is to continue to produce musicians. He is careful never to give Michael any individual or provocative views on the subject (as Stead’s characters on the contrary always have excitingly personal views). No, the whole “northern thing” has been taken over—Seth is adept at taking over old forms to his special purposes—only for the opportunity it offers to strike further chords of poignancy, further variations on the theme, or rather mood, so clearly announced in the book’s opening lines.

Deprived as it may or may not be, the north is generous in this regard: it gives our author, among other poignancies, the aging, beaten father attached to his decrepit cat, the image of Michael as a boy lying on the Pennine uplands listening to the larks, and the wholesomeness of the dying benefactress who years ago introduced the infant Michael to music and who now lends him her extremely valuable Italian violin, without which he would be hard put to continue in the quartet. At the end of the book he will crumble some homemade Christmas pudding onto the snowy moors in her memory.

Admiring, if we will, the cleverness of this choice of setting, we can now turn to the main plot with a proper sense of what Seth is up to. Everything will be arranged to generate the maximum poignancy: “issues,” whether moral, social, or existential, will, like the decay of the north, be drawn on only insofar as they sustain the right note on the heartstring, then they are rapidly dropped. Vienna will be the venue where it would be disastrous for a musician to perform badly. Venice will do traditional service as the right place to have a romantic interlude that is only an interlude. Even music itself, ostensibly the book’s great theme, will be understood first and foremost as a vehicle of sentiment. Thus, after the vision of the long-lost Julia on the bus, Michael, rehearsing the now even more significant quintet, remarks:

For me there is another presence in this music. As the sense of her might fall on my retina through two sheets of moving glass, so too through this maze of motes converted by our arms into vibration—sensory, sensuous—do I sense her being again. The labyrinth of my ear shocks the coils of my memory. Here is her force in my arm, here is her spirit in my pulse. But where she is I do not know, nor is there hope I will.

Wrong! Michael is wrong. For though on crowded Oxford Street he fails to catch up with Julia’s bus in time (Seth’s research letting him down here a little, one feels), the charming lady will turn up of her own free will at the end of the quartet’s concert at the prestigious Wigmore Hall. There are tentative, poignantly uncommunicative meetings. We discover that Julia is married, loves her husband, and has a son who goes to school only a stone’s throw from Michael’s flat. Thus understandably hesitant, nevertheless—for the old magic is at work and the plot must move on—she succumbs and the couple make love. As they prepare to do so, watch how cleverly and tenderly the moral question is fielded:

She smiles, a little sadly. “Making music and making love—it’s a bit too easy an equation.”

“Have you told him [the husband] about me?” I ask.

“No,” she says. “I don’t know what to do about all this subterfuge: faxes in German, coming up to see you here…but it’s really Luke [the son] who I feel I’m…”

“Betraying?”

“I’m afraid of all these words. They’re so blunt and fierce.”

Indeed they are. But Julia need not worry, irony wouldn’t fit in with the particular effects Seth is after here. He will do his best to make sure that both characters remain not only sympathetic, but somehow innocent. That way we can savor their sadness without any irritating distractions. After all, this is not the ordinary affair in which Dionysus bursts on a tranquil scene and the hitherto placid weavers discover a dark side to themselves that they never imagined. The sex is toned delicately down. The Bach is turned decorously up. The lovers play music together. And are they not anyway entirely justified—if justification is required (they both seem to feel it is)—by the fact that this is old and unfinished business between proven soul mates? “I am not seeing anyone new,” Michael truthfully tells the worried Virginie.

Without recounting the whole story, it remains, as far as the plot is concerned, to consider Seth’s masterstroke, the ploy that allows him to sustain his melancholy medley for the full 381 pages (the book makes much in musical terms of the problems of sustaining notes and intensity). Those awkward first meetings between Michael and Julia are suddenly explained by the fact that our heroine is going deaf, indeed is already on the brink of total soundlessness. Against all the odds, she is trying to keep this disability a secret in the hope that she will be able to pursue her career regardless. Aspiring novelists will be able to profit at this point from considering how this desperate response to personal tragedy, together with a great deal of other preparatory stage-setting, allows Seth to get away with the extraordinary coincidence of its being Julia—Julia whose whereabouts, we remember, Michael was unable for ten years to trace—who is now suddenly and without his knowledge invited to substitute for a sick pianist who was to support the quartet at its crucial performance in, of all places, Vienna, where the lovers had originally met.

In his author’s note Seth acknowledges help from “those who understand the world of the deaf—medically, like the many doctors who have advised me, or educationally, in particular my lip-reading teacher and her class, or from personal experience of deafness.” Fascinating here, and alas typical of so many contemporary novels, is the way the solemn appeal to research and veracity in some specialist field is actually used to mask the failure to engage a far more interesting but arduous and less immediately glamorous subject. The idea of a couple with special talents and sensibilities rediscovering each other many years later and finding that their original bond does indeed challenge relationships formed since is intriguing and immediately presents itself as a vehicle for all kinds of drama, reflection, and moral dilemma. What might such a plot have become in the hands of Lawrence, or James, or Moravia, or Elizabeth Bowen? But as soon as we discover that Julia is afflicted with deafness, we have moved into the realm of kitsch. Despite the occasional attempt to link her silent world with the musical realm of communication beyond words, it is clear that the plot is now being driven by the merest appetite for pathos and melodrama.

A party to his lover’s terrible secret, Michael is inevitably brought into conflict with his quartet colleagues who will be risking their reputations when they play with Julia in Vienna. The reader grows anxious over the big night. The narrative tension works splendidly. We are well manipulated. Some will have to pull out their handkerchiefs. The downside is that it allows Seth to get away without developing the characters of the lovers or the dynamic of their relationship, which, as a result, can very adequately be summed up thus: at best diffident initially, Julia briefly indulges a tediously insistent Michael to the extent of agreeing to a few days together in Venice after the Vienna concert, then sensibly and predictably withdraws, leaving him in much the position we found him at the beginning of the book.

Of the characters in A Suitable Boy, Anita Desai remarked: “They come to us extremely well-equipped with easily recognizable characteristics.” The same is true of those in An Equal Music and in particular of Michael’s fellow members in the quartet, though it has to be said that their rehearsals offer by far the best reading in the book. The ever irritable and aggressive, but also gay and vulnerable first violinist Piers, his winsomely accommodating sister Helen, the overly diligent cellist Billy—eager to pose problems the others haven’t noticed—and Michael himself, pragmatic, gruff, always in danger of distraction: this is a force field that works and offers welcome relief from the heady monotony of the love affair. It is also the element that comes closest to evoking the uniting power of music, this picture of four people who have no special desire to spend time together nevertheless sharing the transport of the work they are playing, enjoying the pleasure of a communication beyond words, beyond deafness, and to a certain extent beyond the grave. As they perform Bach together, Michael reflects: “Our synchronous visions merge, and we are one: with each other, with the world, and with that long-dispersed being whose force we receive through the shape of his annotated vision and the single swift-flowing syllable of his name.”

Leaving aside the swiftness or otherwise with which the syllable “Bach” might be said to flow, how seriously are we to take this idea and its latent transcendentalism? Does it convince? There is a determined intertextuality to Seth’s writing in this book. “Under the arrow of Eros I sit down and weep,” Michael tells us in Piccadilly Circus, having failed to catch up with Julia’s bus. London’s monuments and Michael’s desperation are thus fused in an echo of Psalm 137 and its many subsequent literary adaptations. Having been treated to some gruesome Rochdale gossip on deaths, births, and divorces, the sensitive Michael’s mental wince is registered in a one-line paragraph: “For better or worse, unto us a child, ashes to ashes.” Later, as he faxes Julia in German to mislead her husband, Walter Scott is on his mind: “It is a tangled web that I am weaving,” he comments, reminding us of Marmion.

These frequent echoes, literary or biblical, are invariably deployed at moments of emotional intensity and seek to establish with the reader a community of sensibility similar to that experienced by the musicians as they play. It is a community from which the insensitive—the bank employee who refuses Michael a loan to buy a new violin, the benefactress’s nephew who selfishly seeks to repossess the expensive Tononi—will necessarily be excluded. Toward the end of the novel, as Michael’s suffering grows more intense, the literary references become more frequent and are now accompanied by a fragmentation of thought in what amounts to a pastiche of modernism. In the following passage Julia has just ushered her unwelcome ex-lover out of her house with a very decisive goodbye. The little dog mentioned is a reference to the knowing creature in Carpaccio’s Saint Jerome cycle, which the couple saw together in Venice. Shakespeare and Eliot are also present and, who knows, perhaps Twain as well:

The door opens, closes. I look down from the top steps. Water, full fathom five, flows down Elgin Crescent, down Ladbroke Grove, through the Serpentine to the Thames, and double-deckered red vaporetti sputter like Mississippi steamboats down its length. A small white dog sits on the sneezing prow. Go, then, with the breathing tide, and do not make a scene, and learn wisdom of the little dog, who visits from elsewhere, and who knows that what is, is, and, O harder knowledge, that what is not is not.

In a forthcoming novel by the South African writer J.M. Coetzee, the main character becomes aware that the literary project he is engaged in is going badly wrong, it “has failed to engage the core of him. There is something misconceived about it, something that does not come from the heart.”3 We are thus given to understand that if, on the contrary, the story that involves this man is totally electrifying from beginning to end—and it is—then that must be because it is extremely close to Coetzee’s heart. It matters to him in the same way that, for all kinds of reasons, industrial England mattered very much to Christina Stead when she wrote Cotter’s England. That there is something at stake in a narrative, something that engages the core of an author’s being, does not of course guarantee that a reader will be seduced, but it does seem to me a sine qua non of such seduction. However eager to entrance us Seth may be, derivative artifice of the kind he is deploying here seems no more than a tiresome literary exercise. If the story does matter to him, he hasn’t found a convincing way of conveying it.

Which brings us at last to the title of the book and to John Donne. Seth seeks to tie together literary reference, musical experience, and metaphysical consolation by prefacing his work with a quotation from the great dean and poet:

And into that gate they shall enter, and in that house they shall dwell, where there shall be no cloud nor sun, no darkness nor dazzling, but one equal light, no noise nor silence, but one equal music, no fears nor hopes, but one equal possession, no foes nor friends, but one equal communion and identity, no ends nor beginnings, but one equal eternity.

Modern ears cannot help but wonder at such confident and eloquent declarations of faith. Yet overcoming for a moment our sense of awe, it is interesting to see how the term “equal” emerges here as the result of Donne’s systematically denying all those tensing polarities—cloud/sun, darkness/ dazzle, noise/silence, hope/fear—that make our mortal life what it is. In short, “equal” becomes a word that we can use to evoke the unimaginable, something beyond tension, beyond life, beyond individuality.4 This is rather more radical than Michael’s sentimental sense of the presence of others, even the dead, when he plays his violin: “The attendant ghosts press down on me…. Schubert is here, and Julia’s mother. They attend because of the beauty of what we are re-making.” All the same, in the last pages of the book, when Michael has gone to hear Julia giving a solo performance of one of the pieces of music that meant much to them both, Seth boldly attempts to clinch all his interconnections thus:

There is no forced gravitas in her playing. It is a beauty beyond imagining—clear, lovely, inexorable,…the unending “Art of Fugue.” It is an equal music.

But of course it is not, not in the sense Donne meant it, which is the only sense one can think to ascribe to this odd expression. What else could it mean? Only a moment later, in fact, Seth, himself all too familiar with “forced gravitas,” is remarking that the human soul “could not sustain” too much of this music, whereas Donne was affirming his belief in a music that will entertain the soul, or rather the many souls made one, for all eternity. Donne was stating his faith in something he truly couldn’t imagine. Seth’s “beyond imagining,” on the contrary, is the merest inflation: here we have a deaf woman playing Bach superbly, and though that may stretch the imagination, a good performance of Bach is far from beyond imagining.

Once again we have an inappropriate appropriation. Seth needs his vague transcendentalism, his lyricism and literary gesturing, his sense of community in pathos, to sugar this admittedly long but in the end far from hard look at unhappiness. We were thus mistaken when we imagined that An Equal Music might mark a radical departure from Seth’s previous two books. It is once again a calculated exercise in crowd-pleasing and as such the sickly music it generates is one with which the ever vigorous, sometimes vicious Donne, the Donne for whom so much, in love and in religion, was always at stake, would have had nothing whatever to do.

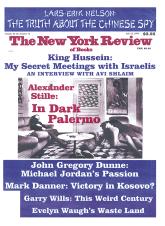

This Issue

July 15, 1999

-

1

See Desai’s review, The New York Review, May 27, 1993.

↩ -

2

The US title was Dark Places of the Heart (Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1966).

↩ -

3

Disgrace by J.M. Coetzee, to be published in the US in 2000.

↩ -

4

Interesting to compare Beckett in Molloy here: “What I liked in anthropology was its inexhaustible faculty of negation, its relentless definition of man, as though he were no better than God, in terms of what he is not.”

↩