As an autobiographer, John Richardson has a great deal going for him. He has been in and around the international art world for many years. He can tell a story as well as anyone in town. If he has ever spent time with a bore, we don’t hear about it. In his fields of particular interest, which are nothing if not varied, he has been “everywhere” and known “everyone.” In person, he can summon up the look of a “most potent, grave and reverend signior,” only “to discard it in a flash when laughter looms.” Though currently best known for his ongoing and monumental life of Pablo Picasso, he has perfect pitch for the human comedy and no inhibitions whatever about setting it down in its every detail.

From “Army and Navy Child,” the opening chapter of The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, we learn that he was born in 1924, the son of a seventy-year-old father and a delightfully pretty woman half his father’s age. They had got together at a time when she was earning her living by retouching photographic portraits in the Army & Navy Stores. (Conceivably it is in part from his mother that John Richardson inherited his very sharp eye for a retouched work of art.)

The Army & Navy was at that time the best and biggest general store in London, and her suitor stood high in its echelons. Knighted by King Edward VII after long and distinguished service in the British army, Sir Wodehouse Richardson had been one of a group of twelve young subalterns who founded around 1870 what was to become a series of enormous and hugely profitable department stores at key points in the British Empire.

To shop at the Army & Navy, whether in London, in Bombay, in Calcutta, or in Aldershot, Plymouth, and Portsmouth (key centers in England for the British army and navy) was a badge of rectitude for many thousands of British families. It was the British world in miniature. Its catalog (a thousand pages and counting) was, as Richardson says, “the Bible of the British Raj.” The Army & Navy Stores could meet all your needs, from childhood onward, and when you died a coffin exactly your size would be waiting for you in the appropriate department.

As the first-born son of the vice-chairman of the Army & Navy Stores, John Richardson as a small boy had the run of the stores and was treated by the staff, as he says, “like a little prince.” (A framed photograph of him was hung in one of the elevators.) He was much loved by his father, and it was reasonable to suppose that he would inherit a major share in a business on which the British Empire had come to rely. How could it be otherwise, when his father had been entrusted during the South African Wars with the formidable responsibilities of the Quartermaster General? As such, he had sole responsibility for the quartering, encampment, marching, and equipment of his troops. A comparable versatility would surely have given him an impregnable position as vice-chairman of the Army & Navy Stores.

But he seems not to have readied himself for civilian life. And, in any case, the old-fashioned stores were about to founder, as was the British Empire itself. Richardson’s father had never saved much money, and even the family’s private bank—once a favorite with many an Indian prince—had got into the wrong hands. After his father died of a stroke in June 1929, the little prince lost his coronet and his mother had to sell the big villa near the Crystal Palace in London and take her three children to much smaller quarters in South Kensington.

When we read of these matters, and of the problems that arose from his father’s having married a relatively lowly employee in the Army & Navy Stores, we feel that John Richardson was interesting even before he was born. When he found out that many of his mother’s family had been in service on one or another of the Rothschild estates in the Thames Valley, he did not repine, but was proud to think that his maternal relatives had given satisfaction to such exigent employers.

“Over the years,” he says in this consistently amusing book,

my upstairs-downstairs background has proved, if anything, an advantage. I like to think that it has enabled me to see things simultaneously from very different angles, like a cubist painter, and arrive at sharper, more ironical perceptions.

He learned in childhood that life has its downs as well as its ups. But when he was thirteen there was just enough money for him to go to Stowe—one of the more permissive and hyperintelligent of British public schools, and beyond a doubt the most beautifully housed. He also learned, and never forgot, that when pleasure was at the helm he could get away with almost anything. Stowe, with its façades by Vanbrugh and Robert Adam and its grottoes, its temples, and its follies, all spoke for delight. So did the inspired landscaping of Capability Brown. In the eye-music of Stowe, arousal was everywhere.

Advertisement

“Those were the scenes,” our author tells us, “of my first sexual experiences.” As on other occasions recounted in this book, Richardson was not exacting in the matter of bedsprings, fine linen, and a stylish interior. For this reason, he says, “one of those escapades ended ignominiously. A friend and I were caught on a rug in a distant folly by the Hunt Club: the club’s pack of hounds had mistakenly followed our scent. There was a lot of ribald ragging, but the urbane, supposedly gay headmaster, who must have heard of it, failed to take punitive action.”

Stowe also did Richardson a decisively good turn in quite another context. It had a progressive art school in which he could study the current Parisian avant-garde art magazines at the time of their publication. From them, and from regular visits in London to Zwemmer’s art bookshop in the Charing Cross Road, he learned fast. Rare was the London schoolboy who reserved for himself a copy of Picasso’s great print Minotauromaquie. (His conventionally minded mother vetoed the project.)

The outbreak of World War II in September 1939 changed everything for everyone, more or less, in London. “I enjoyed the Blitz,” John Richardson writes, in words that many Londoners would second. “It brought out the good nature in even the nastiest people.” Himself exempted from military service on account of having had rheumatic fever, Richardson worked as an industrial designer and was on call at night for civil defense. Large sections of London at that time were anything but sedate. In just a page or two, Richardson gives an account of “the way we lived then” that will ring totally true to survivors of that place and that time. In the world of art and letters in London during the war, very few people made much money. As against that, it was a world in which everyone knew everyone else. If they didn’t, it could be arranged. There were hospitable houses in which any new young man who was clever, deft, and presentable would be welcome. Society was to take some years to return (if it did at all) to the wary formulae of peacetime.

In this free-floating Bohemia, gay men floated even more easily than straights. For one thing, they were more fun. In conversation, they were quicker off the mark. When faced with a new environment, they were more appreciative. They also often brought with them a feral atmosphere that communicated itself even to those who would never be preyed upon. Add to all this a gift for competitive mischief that had been perfected at Oxford or Cambridge, and the makings of a memorable evening were complete. Evenings of that kind were theater. They could also lead to fateful conclusions. In the spring of 1949, John Richardson was taken to a party given by John Lehmann, the editor of New Writing. The party was in honor of Paul Bowles and his new novel, The Sheltering Sky.

Bowles had brought with him a supply of hashish fudge to supplement the thin pickings offered in the way of drink by their host. To those who had never before heard of it, let alone sampled it, the fudge went down like carrot cake. Recklessness resulted. And when Richardson realized that he was being stalked by a stout pink man in a loud pink suit, he recognized that this was Douglas Cooper, who was known to have a remarkable collection of modern paintings, and to be a deeply informed if idiosyncratic expert on modern art.

He was also known to regard Britain’s national museums as absurdly negligent in their attitude toward what was then classified as “Modern Foreign” art. It was their duty to show the best of what had been done in Europe in the twentieth century. Yet fifty years later, there is something ludicrous about the list of “Modern Foreign” artists, including not only the Cubists, but virtually the whole gamut of major modernists, from Matisse to Mondrian, who had been ignored by the Tate Gallery. Douglas Cooper thought that he alone could right that wrong. If he could dictate the Tate’s purchasing policies, what had long been a desert of dullness (as he saw it) would burst into flower. There was also the possibility that he would one day give or bequeath part or all of his ever-burgeoning collection of Cubist and other modern painters to the Tate.

The trouble with this idea was threefold. The Tate was responsible to the British Treasury. Its staff were civil servants. The Treasury would certainly not allow a newcomer to walk in and ride herd over them. Nor would the trustees, not one of whom at that time was convinced of the superiority of “Modern Foreign” art. Many of the trustees were country gentlemen who came up to London only for the trustees’ meetings. They would never argue strongly for a controversial purchase.

Advertisement

John Richardson was naturally eager to see the Cooper collection, but he had been warned by a painter friend, Francis Bacon, that he could easily get to see it, but at his own risk. Cooper would try to lure him into bed, and then turn on him. “He always does,” said Bacon.

On that first evening, Cooper did indeed agree to show him his pictures. He turned out to have astonishing gifts as a cicerone. Not only did he know his subject minutely, but he had a torrential eloquence. When in full cry he made a gigantic, unstoppable noise that was peculiar to himself, with an accent whose origin had never been located. He could provoke uproarious laughter, but he could also strike terror by reason of the almost apoplectic malevolence with which he would abuse those (and they were many) of whom he disapproved.

John Richardson is admirably clear, plain, and fair in his presentation of Douglas Cooper. Very few people knew then, and not many know now, of the reasons for Douglas Cooper’s hatred of England. It was an obsession with him that he was so often regarded in England as an arriviste Australian whose money derived from something called “Cooper’s sheep-dip.” He was, in fact, the descendant of English traders who had sailed to Australia and made an enormous fortune by the middle of the nineteenth century. The biggest shippers of gold in Australia, they also owned much of the Woollahra section of Sydney, which was to become prime real estate. His great-grandfather became Speaker of the House of Parliament of New South Wales in 1856 and was made a baronet in 1863. Thereafter he and his descendants lived more and more in England. Douglas Cooper himself had never been to Australia.

It was because of this background, in Richardson’s view, that Douglas Cooper wished to distance himself as far as possible from English norms of behavior, speech, dress, and civility. But on that evening in 1949, he was out to seduce. He was also delighted to find a more than personable young man who wanted to learn from him, and from his collection.

When Cooper had turned twenty-one in 1932, he had inherited a trust fund that was the equivalent at the time of about $500,000. Cubist paintings were not then expensive. (Richardson tells us that Cooper acquired his greatest Picasso, the Nudes in the Forest of 1907, by redeeming it from a pawnshop in Geneva for $10,000.) He also says that by September 1939 Cooper had acquired “some 137 cubist works, a number of them masterpieces.”

Cooper’s obsession was with what he rightly called “the True Cubists”—Fernand Léger, Juan Gris, Pablo Picasso, and Georges Braque. There was little or nothing to represent them in British museums. Nor had any private collector in Britain set out to collect them methodically, year by year and phase by phase. Cooper was the very opposite of the miscellaneous collector who bought a little of this and a little of that. He wanted a stern logic to power his every purchase.

By the time he and John Richardson got together, Cooper had put his wartime experiences to good use. After being awarded the French médaille militaire for his conduct as an ambulance driver during the collapse of France in 1940, he was given a commission in British air force intelligence. It turned out that he not only spoke German perfectly but was able to counterfeit a wide range of local accents. Richardson brilliantly describes how, with his natural inclination to bully and berate, and with his fiendish cunning and ability to court and charm for his own reasons, he was a formidable and tireless interrogator.

Near the war’s end, Cooper was re-assigned to the Monuments and Fine Arts branch of the Central Commission for Germany. For this he was ideally suited. It enabled him to go from place to place in Europe in what was in effect the role of an independent prosecutor who could hunt down those who had stolen, looted, or in one way or another taken unlawful advantage of wartime conditions in Europe. Here again, Richardson has been able to reconstruct their activities from freshly discovered sources.

Richardson’s first meeting with Douglas Cooper in April 1949 resulted in a mentor/pupil relationship that had an enormous potential for collaboration on work on modern art. Cooper had turned into “a genial sorcerer, immensely informative and enthusiastic and occasionally very, very funny.” But the relationship had inbuilt hazards. After a noggin or two of delicious framboise, Cooper “made the inevitable pass. Out of courtesy and curiosity,” Richardson says, “I lurched upstairs after him.”

I was twenty-five (thirteen years younger than Douglas) and, in those days, extremely insecure and out to please. Alcohol overcame my first revulsion. A kiss from me, I fantasized, would transform this toad into a prince, or at least a Rubens Bacchus. However, Douglas turned out to be as rubbery as a Dali biomorph. No wonder he was mad at the world. This realization triggered a rush of compassion, which enabled me to acquit myself on this ominous night…. For better or worse, my fantasy worked.

For a time, Cooper was a changed man. The fairy tale had spoken true. “But,” Richardson goes on, “there was something that the fairy tale failed to reveal. The moment kisses cool, the Prince turns back into a toad—or, in Douglas’s case, a bad, bad baby, who requires a lot more affection to be cured of his tantrums.”

For the next twelve years, Douglas would play on my compassion, alternating cajolery with brute force, psychic cunning with infantile bellowing. The tension was often excruciating, but the Tolstoyan bond that developed between us—a bond forged out of a passionately shared experience of works of art—made it all worthwhile.

At that point in Richardson’s life, to be with the man whom he describes as “a hugely gifted, hugely flawed old buffo” had many rewards. Europe in the late 1940s and early 1950s was still in convalescence. The tourist industry was hobbled by postwar restrictions. Every day spent out of England could result in reunions that had been out of the question since 1939. There were things to see, people to see, ideas to exchange. Cooper had a sense of fête and on such occasions—and they were many—he could be a one-man gala. No one could have had a better introduction to Europe than the “Grand Tour” on which Douglas Cooper took him to France, Holland, Germany, Austria, Switzerland, and Italy.

Richardson writes that “Douglas was at his best—warmest, funniest and most amenable—with a favored few in his field with whom he could talk shop.” On such occasions, he was the reincarnation of Verdi’s Falstaff as he leads into the great final comic fugue with the words “Tutto nel mondo è burla.” At such times all the world did indeed seem a joke, for the “favored few.” As a host, he could be irresistible. But “favored few” status could be rescinded at any time, and envenomed persecution would take its place.

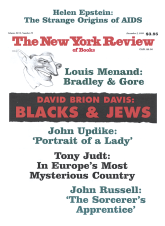

The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, subtitled “Picasso, Provence, and Douglas Cooper,” is a many-layered book. As a come-on, this may be seductive. But it leaves out the central fact about the book—which is that it is really a free-form autobiography. It is to English memoirs of the postwar years what Alfred de Musset’s Confession d’un enfant du siècle was for France in 1836.

Picasso is certainly on stage for much of the second half of the book, and the reader has a front-row seat. Provence is a continual presence from the moment that Cooper and Richardson saw, fell in love with, and bought the spectacular Château de Castille near Avignon. And Douglas Cooper? He is the wild card that at any moment may cause either joy or havoc, or both at the same time.

Richardson the storyteller is at his best about the discovery of Castille. It was a moment at which the pair’s fortunes were in the ascendant. They had paid their first visit to Picasso at Vallauris and had established a lasting rapport. Meanwhile, each morning in Provence, “we would set forth in quest of three-star monuments and meals. On one never-to-be-forgotten day, we took off for a change toward the dilapidated duchy of Uzès.”

En route, we were stunned by the sight of a cluster of golden columns on the edge of a vineyard. We stopped the car and found ourselves in front of a scaled-down version of Bernini’s colonnaded peristyle in the forecourt of Saint Peter’s. Part of the peristyle, which had been quarried from the same sandstone as the Pont du Gard, had fallen down—in an earthquake some thirty years earlier—but so picturesquely that Pannini might have stage-managed it.

What made the place of more than casual interest was a small sign on one of the columns, proclaiming CHATEAU A VENDRE. Little did Douglas and I realize that our lives were about to undergo a radical change.

Thereafter, Picasso figures in the book not only as a great artist but as a country neighbor. (Curiosity soon prompted him to pay an impromptu visit—the first of many—in that capacity.) This proximity, and that curiosity, were of enormous value to both Cooper and Richardson, who thereafter were on call, as it were, while other enthusiasts were kept waiting by Picasso or sent away without a word from the master.

At their first meeting at one of Picasso’s morning levées in Paris, John Richardson was surprised by Picasso’s “smallness and delicacy, also the unassuming courtesy—those radiant smiles—with which he greeted people who seldom had a language or anything else in common with him, and seemed only to want to waste his time.”

“Above all,” he goes on,

I was fascinated by the way Picasso used his huge eyes as a hypnotist might, raking the room for possible subjects. At one moment he turned his eyes on me and held my gaze for long enough to induce a responsive quiver. He was good at spotting susceptible people. After getting to know him better, I would be amused to watch him fix his voracious stare on one unsuspecting person after another—regardless of age or sex. The mirada fuerte, the “strong gaze”—so highly valued by Andalusians, who believe that the eye is akin to a sexual organ and that rape can be ocular—never failed to work its magic.

As will be clear from this and other quotations from his book, John Richardson has a “strong gaze” of his own. And he puts it to work on every detail of their new life in Provence. Much of The Sorcerer’s Apprentice is talked, as much as written. But the talk is sharply focused. The Who’s Who of their house guests in Castille is made up of miniature portraits in which every word tells and nothing essential is omitted. The same gift shows itself in the portraits of places—Uzès, Nîmes, Avignon—that they came to know very well, together with many of their inhabitants. When they arrived in Castille the notion of la vieille France had still some meaning, and every shop was not like every other shop. Personal eccentricities were cherished, like family silver.

John Richardson has also a sharp eye for the coincidences that came with ups and downs of fortune. After looking into the history of the ducal family of Uzès, he was disconcerted to find when checking in at an elegant pension in Marrakesh that the man who carried his bags was none other than the Duc d’Uzès, by then on his uppers. “I gave France’s premier duke a tip,” Richardson remembers, “which he accepted as a condemned man might accept a cigarette from an executioner.”

Short-term guests at Castille were temporarily the “favored few.” Cooper loved his house. He loved the pictures on the walls. He loved the morning mail. He loved to play host. And above all, and quite clearly, he loved John Richardson. Theirs was a lasting romance, and both he and John knew just how to stoke the uproar at the dinner table. The short-term guest would say to himself, “Why should this not go on for ever?” As to why it didn’t, nobody knows more than John Richardson. But those who had to do with Douglas Cooper will know that he was both a builder-up and a destroyer. The one came with the other. When he was on your side, and you were on his, a feeling of shared conspiracy flooded through the relationship.

At a time when I myself was friendly with Cooper, I had organized an exhibition of Dora Maar’s paintings in London. He was delighted. “You are a swift and effective operator,” he wrote. (Since the only painting sold was bought by me, I think that he exaggerated.) When he organized a Picasso exhibition for the Musée Cantini in Marseilles, we had a hilarious meeting at lunch near the harbor and I was able to go around before the opening with Alice B. Toklas, with whom Iwas acquainted. When Picasso appeared, he treated the guards as politely as the rest of us. And when Miss Toklas told him how much she admired one of the earlier paintings in the show, he said, “Ah yes, but then that’s your period, is it not? You came from the same crop!” I am not sure how well she liked it, but she certainly knew how to close her beak.

Not long after that, my friendship with Douglas foundered, in the following manner. One afternoon, there was a meeting of the art committee at the Arts Council of Great Britain. It was my first appearance as a committee member. I had not seen the agenda. Douglas and John were to have dinner that evening with my then wife and myself. I was therefore disconcerted to find that the main piece of busi-ness was the question of who should organize the upcoming Picasso exhibition at the Tate Gallery. It emerged that Roland Penrose, a lifelong English champion of Picasso, had been sounded out about the exhibition for some time. He was a member of the committee, and well liked as a person.

It also emerged that Douglas Cooper had written to everyone concerned and said that Penrose was quite incompetent to organize such a show. His letters attacked not only Penrose himself, but the staff of the Arts Council, the trustees of the Tate, and the London art world in general. The tone of these letters went way beyond anything that is normally encountered in a context of this sort.

Penrose had been asked to leave the room while these letters were read. With every letter, feeling around the table rose higher. Irrespective of who was the better candidate, these were disgusting letters. When it came to the vote, only one of those present voted for Douglas Cooper. This was Benedict Nicolson, the editor of the Burlington Magazine. “I simply think,” he said, “that Cooper would make the better exhibition.” In that, Nicolson was right. But Cooper had defeated himself. It was a crucial and a terrible afternoon—and an uncomfortable evening followed.

As to why and how John Richardson and Douglas Cooper parted company, and what came of it, The Sorcerer’s Apprentice has much to say, not least about Richardson’s being drawn to a new life in New York, which Cooper resented. But the basic fact is that Douglas Cooper was by nature self-destructive and that John Richardson had to lead his life his own way, at no matter what cost. His account of “the way we lived then” is unlike any other in its frankness and its perceptive portraits of people usually seen from afar.

This Issue

December 2, 1999