I took the Lexington Avenue subway

To arrive at you in your glory days

Of the Nineteen Fifties when we believed

That you could solve any problem

And I had nothing but disdain

For “self-analysis” “group analysis” “Jungian analysis”

“Adlerian analysis” the Karen Horney kind

All—other than you, pure Freudian type—

Despicable and never to be mine!

I would lie down according to your

Dictates but not go to sleep.

I would free-associate. I would say whatever

Came into my head. Great

Troops of animals floated through

And certain characters like Picasso and Einstein

Whatever came into my head or my heart

Through reading or thinking or talking

Came forward once again in you. I took voyages

Down deep unconscious rivers, fell through fields,

Cleft rocks, went on through hurricanes and volcanoes.

Ruined cities were as nothing to me

In my fantastic advancing. I recovered epochs,

Gold of former ages that melted in my hands

And became toothpaste or hazy vanished citadels. I dreamed

Exclusively for you. I was told not to make important decisions.

This was perfect. I never wanted to. On to the hartru surface of my emotions

Your ideas sank in so I could play again.

But something was happening. You gave me an ideal

Of conversation—entirely about me

But including almost everything else in the world.

But this wasn’t poetry it was something else.

After two years of spending time in you

Years in which I gave my best thoughts to you

And always felt you infiltrating and invigorating my feelings

Two years at five days a week, I had to give you up.

It wasn’t my idea. “I think you are nearly through,”

Dr. Loewenstein said. “You seem much better.” But, Light!

Comedy! Tragedy! Energy! Science! Balance! Breath!

I didn’t want to leave you. I cried. I sat up.

I stood up. I lay back down. I sat. I said

But I still get sore throats and have hay fever.

“And some day you are going to die. We can’t cure everything.”

Psychoanalysis! I stood up like someone covered with light

As with paint, and said Thank you.

It was only one moment in a life, my leaving you.

But once I walked out, I could never think of anything seriously

For fifteen years without also thinking of you. Now what have we become?

You look the same, but now you are a past You.

That’s Fifties clothing you’re wearing. You have some Fifties ideas

Left—about sex, for example. What shall we do? Go walking?

We’re liable to have a slightly frumpy look,

But probably no one will notice—another something I didn’t know then.

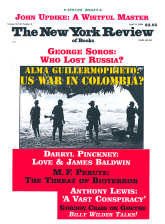

This Issue

April 13, 2000