Franz Schubert, Opus Posth.

The train stopped in a field; the sudden silence

startled even sleep’s most ardent partisans.

The distant lights of shops or factories

glittered in the haze like the yellow eyes of wolves.

Businessmen on trips stooped over their computers,

totting up the day’s losses and gains.

The stewardess poured coffee steeped in bitterness.

Ewig, ewig, last word, “Song of the Earth,”

it repeats so often; remember how we listened

to this music, to the promise that

we so longed to believe.

We don’t know if we’re still in Holland,

this may be Belgium now. No matter.

An early winter evening, and the earth hid

beneath thick streaks of dusk; you could

sense the presence of a canal’s black water,

unmoving, stripped of mountain currents’ joy

and the great amazement of our oceans.

Wolves’ yellow eyes were quivering with a nervous

neon light, but no one feared an Indian attack.

The train stopped at that moment when our reason starts

to stir, but the soul, its noble yearning, is asleep.

We were listening a different time to Schubert,

that posthumous quintet where despair declares itself

insistently, intently, almost insatiably,

renewing its assault on the indifference

of the genteel concert hall, ladies in their furs

and reviewers, minor envoys of the major papers.

And once out walking, midnight, summer in the country,

a strange sound stopped us short: the snorting and neighing

of unseen horses in a pasture. As though

the night laughed happily to itself.

What is poetry if we see so little?

What is salvation if there is no threat?

Posthumous quintet! Only music keeps on growing

after death, music and the hair of trees.

As if rivers gave ecstatic milk and honey,

as if dancers danced in frenzy once again…

And yet we’re not alone. One day some timeworn

guitar will start singing for itself alone.

And the train moves at last, the earth rocks

underneath its stately weight and slowly

Paris draws close, with its golden aura,

its gray doubt.

To See

Oh my mute city, honey-gold,

buried in ravines, where wolves

loped softly down the cold meridian;

if Ihad to tell you, city,

asleep beneath a heap of lifeless leaves,

if I needed to describe the ocean’s skin, on which

ships etch the lines of shining poems,

and yachts like peacocks flaunt their lofty sails

and the Mediterranean, rapt in salty concentration,

and cities with sharp turrets gleaming

in the keen morning sun,

and the savage strength of jets piercing the clouds,

the bureaucrats’ undying scorn for us, the people,

Umbria’s narrow streets like cisterns

that stop up ancient time tasting of sweet wine,

and a certain hill, where the stillest tree is growing,

gray Paris, threaded by the river of salvation,

Krakow, on Sunday, when even chestnut leaves

seem pressed by an unseen iron

and the sorrow of old women in new projects

on the outskirts of Barcelona;

vineyards raided by the greedy fall

and by highways full of fear;

if I had to describe the night’s sobriety

when it happened,

and the clatter of the train running into nothingness

and the blade flaring on a makeshift skating rink;

I’m writing from the road, I had to see

and not just know, to see clearly

the sights and fires of a single world,

but you unmoving city turned to stone,

my brethren in the shallow sand;

the earth still turns above you

and the Roman legions march

and a polar fox attends the wind

in a white wasteland where sounds perish.

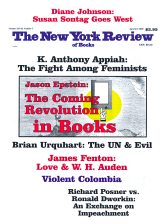

This Issue

April 27, 2000