Murray Kempton wrote the following in July 1992, just before he left New York to cover the Democratic National Convention.

My next national convention will be the twenty-first of those occasions when I have intruded my fleshly and decreasingly spirited presence upon the company of Democrats, Republicans—and once even Progressives—at their quadrennial abandonments of reason.

Sixty years ago the miracle of bringing the conventions alive for untraveled Americans was work for the radio alone, and it did that office more than handsomely, by reducing commentary to a minimum and leaving the tale to be told by the delegates in a jumble of regional accents and regional prejudices conjuring up the image of a vast continent of exotic provinces, each with its own language.

It was the radio that bound me in a thralldom to the convention process that has only lately commenced to slacken. I was listening to the first bal-lot of the 1932 Democratic convention that nominated Franklin D. Roosevelt. Tammany Hall, which hated Roosevelt, had demanded a poll of the New York delegation. The convention chairman complied, and when the roll of name after name arrived at James J. Walker, the answer came back bold as brass: “Alfred E. Smith.”

Franklin D. Roosevelt was governor of New York State and Jimmy Walker was mayor of New York City. The powers of the governor included removing any mayor who had too far disgraced his office; and the Walker administration’s scandals had already provided excuses more than sufficient. But with his head in Roosevelt’s hands, Jimmy Walker had coolly bared his neck and given the knife license to do as it pleased. Roosevelt was more than pleased to expel Walker from City Hall within the month.

I was, of course, too young to know the what and why of this moment; but somehow I could sense its gallantry from the silence of the hall and the chairman’s respectful pause before returning to his call of the roll. He and I and all who listened had heard the defiant voice of one more of those lost causes that have ever since been my incurable addiction.

The first stages of love are unfortunately too often the sweetest. For they’re the ones when we feel the drama without quite understanding it. That may be why my own romance with political conventions has lost so much of its bloom: the better I learned to understand their dramas, the less intensely I felt them. But then they’ve pretty well withdrawn permission for dramas anyway.

My earliest steps on a convention floor were with the Democrats in 1936. Luck had blessed me with a job carrying telegraph copy for Western Union.

I would stand in the press rows where Henry Mencken sat weaving gold from the straw of podium discourse while journalists at leisure craned over his shoulder to watch his next marvel clatter forth. No graven image could be more serenely unconscious of its devotees than Mencken was; he would type on, finish a page, hold it up on an uplifted arm to be seen and seized by one of us Western Union boys, and, having never turned around, go back to typing.

I came back from this first brush with two useful lessons. Mencken had taught me by example that the best way to do the job was to sit down with my typewriter just before the gavel and then record the event just as it unfolded, trusting that enough surprises and amusements would bob up to keep the account lively.

I had also found out that a Western Union messenger was free to pass unquestioned wherever he chose. For years I kept the pin that simply said “Western Union,” with no further need for credentials, and managed to squirrel my way into no end of secret conclaves full of portent if barren of revelations. Neither lesson is serviceable by now. Western Union has folded its tents; and the convention managers have exercised themselves so strenuously to curtail their proceedings and to suppress the risks of amusement and surprise that the stuff a running account needs for vigor has all but drained away.

There is no crueler way to assess what conventions have become than to remember what they used to be and notice how carefully their managers have labored to eliminate every one of the unexpected, the untidy, and the disorderly elements whose mixture made for a brew unique for its tang, flavor, and purgatively bitter aftertaste.

We shall never feel again the wicked exhilarations of the sight of the hatred of brother for brother and sister for sister showing the naked face that cares not what visiting strangers might think. There will always be conventions where one set of delegates detests the other; but, since the result is almost invariably known in advance these days, enmity can only manifest itself with the sodden air of depression.

Advertisement

Oh, for the brawls of yesteryear. The Democrats maintained a steadier key of low-level fratricide than the Republicans who, being a church, generally preferred close harmony. But just because they were a church, the Republicans would now and then lurch into some doctrinal quarrel, and rise to savageries of spleen that would turn the hair of a hockey fan.

I had not thought again to hear the sound of a spite so pure as the one rolled down upon Tom Dewey in the roar of the Ohio delegation to the 1952 Republican convention when it recognized that the Eastern bankers had snatched away the Midwest’s chance to crown a President Robert A. Taft. But then I saw Nelson Rockefeller take the microphone at the 1964 GOP convention and be met with the ravening fury of Goldwater delegates envenomed by victory as they had never before been in defeat.

One of the charms of what conventions used to be was their curious habit of passing out a battered trophy to the winner and then heaping all the laurels on the defeated. The most delightful of their vagaries was an insistence upon upstaging the nominee. John F. Kennedy was upstaged at the 1960 Democratic convention by Senator Eugene McCarthy’s futilely magnificent appeal to stand by Adlai E. Stevenson and not abandon the man who had made them all proud to be Democrats. Ronald Reagan contrived with superb delicacy to upstage Gerald Ford barely a minute after he had been renominated for president. Ted Kennedy quite coarsely upstaged Jimmy Carter in 1980; and even Barry Goldwater, who had neither the inclination nor much of the knack for upstaging, brought it off with Richard Nixon in 1960. The best part of what addicted me to conventions was their generosity in giving the best exit lines to the lost cause.

But now every peril of uninvited apparitions of the spontaneous or improvisatory sort has been suppressed. The artlessness of the political convention has given way to the arts of choreographers whose taste forbids any display that might be embarrassing and could in the process remind the beholder of the lives and feelings of the real humanity that can be sometimes inspiring and sometimes deplorable.

The delegates no longer slurp about in their ridiculous hats and with the wound of their hangovers festering for all to see. They sit rigid instead as though they are a congregation. The journalists who used to ring the platform close enough to be rained with the speaker’s spittle are perched in tiers behind it like the audiences for Phil Donahue, with the singular difference that they have become television’s only nonparticipatory audience.

The whole design of these cosmetic revisions was to fit the political conventions to the standards that television was assumed to demand. This vision was by no means ignoble and might have done no harm if its architects had not forgotten that television has no more compelling demand than for the product to be entertaining. The ironic consequence of all these endeavors has been that the conventions are now neat, well-tailored, and disciplinedly staged and so implacably tedious that the networks disdain to give them houseroom for more than a few begrudged and diminishing hours a night.

There are no fights anymore, no life-enhancing accidents, and seldom a barbaric yawp. Oh well. We go listlessly on to them as we might to an alumni reunion where there isn’t much to do except inspect the latest wither on a classmate’s cheeks and agree that the old school was a lot more fun when we were young.

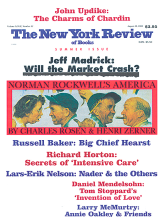

This Issue

August 10, 2000