For me, Lars-Erik Nelson was the best Washington columnist of his time, and his sudden death on November 20 at fifty-nine must be listed under unacceptable losses. His columns for the New York Daily News and Newsday were models of that difficult form, a combination of a humane intelligence, solid reporting, and a supple, fluid style. His writing always sparkled. He liked concrete nouns and active verbs, and each paragraph was as solid as a brick. He avoided pyrotechnics, because the goal was lucidity. The writing only appeared to be simple. It was about as simple as a Matisse. Try doing it. He also avoided writing for cheap applause. For Lars (which is what everyone in the trade called him), his job, as he saw it, was to illuminate, not entertain. And so the tone was always marked by that form of restraint that we sometimes call grace. In this case, the style was the man.

Lars had many other strengths. At the tabloids where he was a columnist, he never wrote down to his readers, because, unlike some of the businessmen who publish newspapers, he actually knew those readers. He grew up with them in Brooklyn. He traveled with them on the subways and sat with them in classrooms at the Bronx High School of Science and Columbia College. He respected them. He trusted their collective intelligence. In an e-mail to me last year, he wrote about his beloved Daily News: “From my standpoint, [Ed] Kosner has been a good editor. He understands the substance of the news, has a sense of fun,…has ideas, listens to ideas and agrees that they are sometimes better than his ideas. He also set the marker that we have to be the smartest paper in the city, which scared some people who thought that meant we were going upscale. It doesn’t; it just means we don’t treat our readers as if they are morons who don’t care about anything but cops, robbers, gossip, fires and sports.”

He believed, as I did, that a dumb tabloid was a tabloid doomed to extinction. When we worked together at Newsday and then at the Daily News, that belief was essential to our friendship. We shared a few other things. We were both from Brooklyn. We had both started out to be painters and joked that we’d failed out of art into newspapers. He was often more excited about the watercolors he was painting and the life class he was attending than about the absurdities of the Contract With America. I was also painting again, and we talked about having a joint exhibition of our work with the proceeds going to some charity. “As long as they don’t throw chairs at us,” Lars said, “it could be a lot of fun.”

That never happened, but art was one of the basic templates of his life. In that e-mail, he cited Robert Henri’s wonderful book The Art Spirit: “He writes that all artists are members of an invisible brotherhood that transcends time and space, and all members recognize one another through the centuries. Then he has a line that goes like: ‘Here is a drawing by Da Vinci. I look at the corner, and I see him in trouble, and I meet him there.'”

As a member of the invisible brotherhood of newspapers (which included, of course, many women), he would often look at a corner—a paragraph, a sentence, a headline—and see another member in trouble and meet him there. With suggestions for improvement. With ideas about follow-up or a tip on writing style. With an unspoken belief in the honor of his craft, a creed absorbed in the city rooms of the New York Herald Tribune (where he was a copy boy), the Bergen Evening Record, and the Daily News. He learned his craft, as we all did then, from older newspapermen and women who had been shaped by depression and war. They helped deepen his sense of proportion about human folly. Their rough codes acknowledged the importance of politics while insisting on maintaining a decent distance from politicians. “They all knew politics was important,” he said to me once. “They knew it had to be in the paper. They just didn’t think you could cover it right if you were in the bag.”

One other experience shaped the mature Lars. In his twenties, he went to work for the Reuters news service and ended up in Moscow (he had majored in Russian at Columbia). He was there between the late Sixties and late Seventies, during the final dismal years of the neo-Stalinist state. He saw what could happen when self-righteous abstraction drove a society and when government fell into the hands of an armed bureaucracy. He learned at first hand what it’s like to live in a great country grown wormy with lies.

Advertisement

As often happens, the experience of life in another country makes you better understand your own. When Lars came home, his basic subject soon became the United States. After he died, it turned out that he had been a registered Republican, but he cherished the liberal values of the American system, its openness, its compassion for the weak, its tolerance, its fairness and common sense. He despised all forms of orthodoxy. He was permanently wary of the American form of apparatchiks, and the drift toward the formation of an American nomenklatura. He had no patience with true believers. In the fevered year that led to the impeachment trial of Bill Clinton, he refused to join the prosecutorial pack; after all, he had lived once in a country where there were too many prosecutors and no defense attorneys at all. “The enemy isn’t conservatism,” he said to me once. “The enemy isn’t liberalism. The enemy is bullshit.”

In that spirit, during the last year of his life he repeatedly directed his indignation at the case of Wen Ho Lee. He exposed the spongy assumptions behind it. He attacked what he saw as careless, agenda-driven reporting by The New York Times, which broke the story and legitimized it. He deplored the hysteria that attended the woolly revelations and the spy fever that contributed to the dispatch of Wen Ho Lee to solitary confinement.

“The first story just didn’t hold water on its own merits,” Lars said in a PBS interview last September, after the Times issued its unprecedented explanation-apology for its role in the case. “They were saying that China had stolen the plans for a bomb, W-88 warhead, that the nuclear balance was shifting, this was the worst espionage since the Rosenbergs, that the suspect was a Chinese-American scientist at Los Alamos. None of that turns out to be true…. There was no skepticism.”

There was no skepticism: the unforgivable city-room sin. “They seemed to be captive of their sources,” Lars said of the Times reporters, adding a few minutes later: “The problem with investigative reporters is they get the scent like bloodhounds. And they just sort of go where the scent leads them and they don’t stop and think whether they’re chasing the right spoor…. Editors tend to go along with them if they’ve invested a lot of time in the case.”

Most newspaper people thought Lars would receive a Pulitzer Prize for his columns on the Wen Ho Lee case, but Lars didn’t really feel a need for the ratification of juries. When I was editing the Daily News, we nominated Lars for the Pulitzer in commentary, and he didn’t win. I called to console him, reminding him that Pearl Buck won a Nobel Prize in Literature, while James Joyce did not. He laughed. “What do I need with a prize?” he said. “I’ve got the best job in the world.”

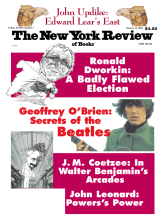

In the past two years, Lars moved his work to another level, showing that he wasn’t just a columnist, master of the seven-hundred-word form, a brilliant sprinter. In nearly twenty pieces for The New York Review of Books (including a detailed summary of the Wen Ho Lee case), and in extended articles for other magazines, he showed the full range of his skeptical intelligence, his ability to look more deeply at the stuff of our politics. For him, reading was also a kind of reporting. He read in genres that would make most of us flee to monasteries: government documents, campaign biographies, congressional transcripts. He came to them with a sense of discovery and a kind of joy. And then wrote his pieces in his characteristic muscular, illuminating prose.

None of his work was predictable, because Lars simply refused to take his ideas off the rack. He hated the glib sneer, no matter who was doing the sneering. He defended Republicans when he thought they were getting a bum rap and attacked liberals when they waved their flags of mindless orthodoxy. In general, he liked politicians. He didn’t dismiss them all as charlatans, liars, or clowns (his skepticism was not cynicism). For example, in many columns he went after the incoherence (and nastiness) of the oratory that accompanied the so-called Republican Revolution, but then he admitted that against all of his instincts he had even come to feel some liking for Newt Gingrich. In his admiring appraisal of John McCain for The New York Review, he wrote:

In a country still divided and troubled over the Vietnam defeat, McCain, a man no one could accuse of having illusions about the Vietnamese regime, offers the possibility both of coexistence with it and of collaborating without rancor with Americans who opposed the war.

“I have a piece on (Janet) Reno coming out in The Nation next week,” he wrote me once. “I say she’s done a good job, over all. It’s sure to infuriate everybody, left and right (It certainly disappointed the Nation editors). But as I get older, I come to realize that the world is inhabited by human beings, with all their flaws and foibles, and it becomes harder to be judgmental. A guy I like, for example, was raking former Treasury Secretary Bob Rubin for failing to foresee the Asian financial crisis. My thought is if somebody as bright as Rubin can’t foresee it, it probably can’t be foreseen. Rubin is as good as we get in this life….”

Advertisement

But politics was not all. The last time we talked, he tried to convince me to write a personal guidebook to New York; I tried to persuade him to take off for a few months and write a book that would make sense of politics in the new century. “You know,” I said, “the kind of book Lippmann would write every couple of years.” He chuckled, as if dismissing any pretensions to being a public philosopher, which, of course, is what he was.

This Issue

January 11, 2001