One of the most endearing qualities of the dead is their reluctance to talk back to us, and the Etruscans, ancient Italy’s most distinctive and enigmatic people, have been no exception. No outraged Etruscan warrior has ever come knocking at the door like the statue of the Commendatore in Don Giovanni, primed to pull an errant archaeologist or a tendentious historian down to Hell for the deceptions they have wrought in the name of scholarship. Instead, constrained to discuss things among ourselves without their help, we strive bravely to reassemble the broken fragments of ancient Etruria into a serviceable past.

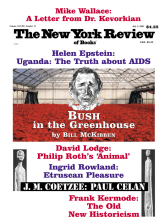

Since 1985, a series of ambitious European exhibitions has focused on the Etruscans in ways that reveal as much about the exhibitors and their times as about the Etruscans themselves. Nineteen eighty-five was Italy’s “Year of the Etruscan,” which featured a huge show in multiple venues called Buongiorno Etruschi—“Hello, Etruscans.” Buongiorno Etruschi called attention not only to this ancient nation of traders, whose merchantmen and pirate ships plied the Mediterranean from the time of Homer’s Odyssey to the beginnings of the Roman Empire and exerted a lasting influence on both Roman and Italian culture. In addition, through its bright, high-tech installations, dense catalogs, and gadget-filled gift shops, the gigantic show proclaimed Italy’s new position among the world’s foremost economic powers, spearheaded by the undisputed international supremacy of Italian design. Buongiorno Etruschi tested, and then savored, the newly impressive force of the phrase “Made in Italy” at a time when the value of the lira nearly doubled against that of the American dollar.

The 1992–1993 exhibition mounted in Paris and Berlin as The Etruscans and Europe flew the starry flag of the nascent European Union, pointing out Etruria’s lasting contributions to a broader European culture, including words like “letter” and “person.” Conceived in the flush of optimism that accompanied the Maastricht economic accords, The Etruscans and Europe actually opened in another mood altogether, as the continent once again faced its fractious past, for by 1993 the former Yugoslavia had exploded, and Sarajevo, not Maastricht, was the name to conjure with. Thus the message of diversity within unity that these European Etruscans had been meant to convey could be contrasted with another possible story: the brutal assimilation of Etruria to Rome during four hundred years of unrelenting warfare, from the conquest and devastation in 396 BCE of thriving Veii, Rome’s nearest Etruscan neighbor, to the slaughter of three hundred elders of Etruscan Perusia on the altar of Divine Julius Caesar on the Ides of March, 40 BCE, their punishment for having backed Marc Antony in his struggle with the ruthless young man who would eventually be known as Caesar Augustus.

Gli Etruschi, the Etruscan show now on view at the Palazzo Grassi in Venice, reflects an Italy that has seen both the economic boom of the 1980s and the sobering disintegration of the former Yugoslavia, a land that borders Italy and has sent more than its share of desperate refugees across their common frontier. In recent decades, Italy’s wealth and political security have attracted extensive immigration from many parts of the world: Albanians who have clung in human clusters to the hulks of their rattletrap ships, Africans swathed in flowing robes, both the white gauze of Eritrea and the brilliant prints of lands further south, Asians in such profusion that filippino has become a synonym for “housekeeper,” Gypsies (whom the Italians now call by their own name, Rom) washed up by the Bosnian maelstrom. One of the show’s significant themes is the extent to which Italy has always been a place where people and cultures have met, mixed, and ultimately created a workable society. In this vision, the Etruscans, the most linguistically and perhaps culturally distinct of Italy’s ancient peoples, also demonstrate how such a nation could maintain itself as indefatigably receptive to other people, other crafts, and, we can only assume (because archaeology has yet to penetrate Etruscan minds), other ideas.

This essential and urgently topical theme receives sturdy support, both literal and figurative, from the excellent catalog, whose bulk is intellectual as well as physical. Italians now call such massive spawn of blockbuster exhibitions il mattone—“the brick”—but Gli Etruschi is a worthy mattone that contains a wealth of new information and some welcome, provocative interpretations of data both new and old.

A second significant theme, not only at the Palazzo Grassi but also in new books like Sybille Haynes’s Etruscan Civilization, concentrates attention on the special status of Etruscan women, who were, by general ancient consensus, the most free and powerful women in the world, shockingly so in the eyes of those Greeks and Romans who did not actually settle down with one of them to live out a wine-watered, well-fed maturity in the hills of Tuscany. For Greek men like the legendary Demaratos of Corinth or the very real Arnthe Praxias of Vulci or the Latin Marce Ursus, the learned and stylish women of Etruria were as irresistible as their bountiful, beautiful land.1

Advertisement

A third emphasis also governs both the Palazzo Grassi exhibition and Haynes’s book, again a direct legacy of fairly recent events. Thanks largely to the towering influence of the late Ranuccio Bianchi Bandinelli, a brilliant archaeologist (he was both a Sienese count and a committed Communist), the Etruscans have spent many decades living out a Marxist parable about the course of human society.2 In recent years, however, this strict Marxist tale has itself been shaped by Italy’s economic growth into its own distinct, revelatory variation, a Marxism charmed by commodities.

Comparison of Haynes’s new book with her ingenious Etruscan novel, The Augur’s Daughter (1981), or of Gli Etruschi with the exhibition The Etruscans and Europe will show how active a part archaeology still plays in our ever-evolving ideas about Etruria.3 The number of new finds in the past twenty years amounts to an extraordinary tally, despite the besetting problem of tombaroli, tomb robbers who are often encouraged by collectors or museums that are content to loot Greek vases from Etruscan tombs because they only care about Greek artists rather than Etruscan patrons—and now, in a dubious sign of progress, are encouraged just as often by unscrupulous or misguided Etruscophiles.4

As Gli Etruschi (both show and catalog) demonstrates at the outset, the Etruscans emerged as a distinct population on the Italian peninsula in the eighth century BCE, gathered in villages of oval-shaped mud huts whose elaborately thatched roofs were woven over prominent rafters, these apparently carved or bent into fanciful bird shapes. They had learned to dig for ore in their wooded hills and to smelt metal from the extracted rocks, bronze and iron especially, from which they fashioned cooking utensils, trappings for horses, and household amenities beautiful enough to suggest that the glories of Italian food and Italian design began right here. One of the small-scale model huts that served many Etruscans as urns for their cremated ashes is made of embossed bronze, its eaves adorned with a dense profusion of tiny metal rings. Perhaps these hut villages jingled with wind chimes amid the trees in the dense Tuscan forests, not yet felled to fuel the smelters’ fires, to fashion the Etruscan ships that plied the Mediterranean, and to build the opulent cities that became the centers of later Etruscan life.

Their expertise in metallurgy propelled the Etruscans into the center of the Mediterranean economy precisely at the moment when the invention of money (by the Lydians of Asia Minor, the people of legendary King Croesus) created a powerful new instrument for international trade. Their bronze—and their bronze-armed warriors—brought in Egyptian gold, Greek wine, Greek olive oil, Phoenician textiles, and a voracious appetite for style. The difference between merchant and pirate was probably as narrow then as it was among Elizabethan privateers; like their Greek contemporaries, Etruscan metalsmiths produced both exquisitely delicate miniatures and stout implements of war.

For two centuries, the seventh and sixth centuries BCE, the Etruscans dominated most of the Italian peninsula and gave their name to the seas that border the Italian coast: the Adriatic was named for the Etruscan trading port of Atria, and the Tyrrhenian Sea repeats the Greek word for the Etruscans, Tyrrhenoi, a sure sign of what Greek traders could expect when they headed their ships into these waters. The extent of Etruscan political might was checked by two forces: a combined Greek navy off Naples in 472 BCE, and eventually, definitively, the expanding power of Rome.

As Gli Etruschi demonstrates convincingly, however, if Etruria eventually became assimilated to Rome, Rome had also become thoroughly assimilated to Etruria. The show suggests, in other words, that different sorts of people can in fact live together while maintaining a certain cultural individuality, although all the parties concerned will also inevitably be changed in the process. To this day, the process of Etruscan assimilation is still far from complete: Tuscany and its inhabitants remain distinct from other Italians, and a good deal of that distinctiveness, physical, culinary, perhaps even temperamental, comes right out of Etruria, as many Florentines or Sienese will remind you, and as one can see from a certain cast of black eye in an angular face, a certain wiry, ageless physique from Volterra to Cortona to Chiusi.

The catalog of The Etruscans takes pains to minimize the reliability of DNA studies performed on Tuscans some ten years ago that showed close similarities to the DNA from Etruscan remains. That skepticism, however well placed with regard to the scientific rigor of the experiments themselves, is perhaps too scrupulous with regard to the essential point of the investigation: your own eyes, and the voices of the Tuscans themselves, will suffice to tell you that the Etruscans are still very much with us. In fact, the probable originator of big, ambitious, elegant Etruscan shows like Buongiorno Etruschi, The Etruscans and Europe, and Gli Etruschi was just such a black-eyed, sharp-featured Tuscan, Lorenzo de’ Medici of Florence, whose fifteenth-century Etruscan museum first presented his region’s primeval culture as the wellspring of all that was civil about Florentine civic life.

Advertisement

What finally put the polish on Etruscan civilization was contact with Greece, which began to exert a transforming effect on Etruscan life in the eighth century BCE. It began with a merchant outpost on a place the Greeks called “Monkey Island”—Pithekoussai—an island in the Bay of Naples. Soon Greek colonies dotted the coasts of Sicily and southern Italy, anywhere that the settlers could find a foothold without agitating Etruscan warriors and their state-of-the-art weaponry. From the seventh century onward, Greek design, Greek drinking habits, and the Greek alphabet swept through Etruria, from its southern outposts around Salerno to the Adriatic trading emporia that had been staked out among the Po River’s many mouths, and this diffusion of Greek culture occurred in significant measure, it seems, through the agency of those enterprising Etruscan women. For nearly a century after they first appear in the seventh century, written Etruscan texts are associated almost exclusively with women’s graves. Five hundred years later, several alabaster funerary urns from Volterra were crowned by little reclining statues of women holding writing tablets. The number of preserved Etruscan inscriptions dwarfs the output—and presumably the literacy—of early Rome; no wonder that well-born Roman boys were sent to study in Etruria and that Rome’s important religious books were apparently written in Etruscan, and used well into the Christian era.

When transplanted to Etruria, the Greek male ritual of the symposium, or drinking party, became a family gathering, husbands reclining at the banqueting couch with their wives, a scene often repeated in Etruscan funerary art, where painted and sculpted couples eat and drink their way through eternity, feasting on prosciutto with figs and melons, roasted meat and a brimming cup of red Tuscan wine—which the Etruscans like the Romans called vinum. Some of these reclining pairs drip perfumed oil on one another; two daring generations of couples from Etruscan Vulci preferred to have themselves portrayed in life-size sculpture in dinner’s afterglow, lying together forever in bed. Some of these well-nourished Etruscans are young and hauntingly beautiful, like the painted Velia Spurinai from a tomb in Tarquinia; many more are not: craggy-faced, potbellied, a little wrinkled, a little thick about the arms, they face eternity as squarely as they faced life, and are no less adorable than their prettier compatriots for their forthright humanity.

As for the Greek designs that began to adorn Etruscan jewelry, cookware, clothing, and monumental architecture, how many of them responded to women’s taste as much as men’s? When Greek potters and Greek goldsmiths settled in Etruria with their Etruscan wives, who told those craftsmen what the local market would bear? At the present state of evidence and archaeological ingenuity, we cannot quite say. We know, however, that the Etruscans rejected as much from Greece as they borrowed. The penetrating feeling for proportion that the Greeks shared with the Egyptians was disregarded in Etruria, nowhere more charmingly than with the long, lean Volterran bronze that greets visitors to the Palazzo Grassi at the top of the grand staircase. He is called the Ombra della Sera, the “Shadow of the Evening,” a name given him by the extravagant twentieth-century Italian poet Gabriele D’Annunzio. A beanpole boy with pixie hair, he stretches to nearly a yard in height, all gangly arms and legs and rounded adolescent belly. For the fifteenth-century Florentine sculptor Donatello, at least, it would be an Etruscan rather than a Greek sensibility that informed his Early Renaissance bronzes, like his own portrait of adolescence, the sexy little David in the Bargello Museum in Florence, whose fluidities of line and striking awkwardnesses can both be compared with the distinctive qualities of Etruscan sculpture.

Some of the differences in a culture’s choice of artistic forms may also lie in such environmental factors as the quality of the light or the availability of certain materials; the stark stone Doric temples of western and mainland Greece developed in glinting light on the rocky terrain of which they seem a natural outgrowth, whereas the mud brick and terra-cotta shrines of Etruria arose under a softer sun on rolling forested hills. And tastes, like peoples, can coexist: Etruscans liked the bold lines and precise detail of the vases they imported from Athens, but they also liked their own chunky black burnished local ware now known as bucchero.

The charms of Etruscan art and the physical beauties of Tuscany itself induce an irresistible temptation to think beyond tracing the histories of stylistic change in Etruscan artifacts or charting changes in Etruscan settlement patterns, port facilities, or building types to create a real history of these people. Our resources for creating such a history are scant and stubbornly intractable; the Greek and Roman historians who wrote about the Etruscans did so from their own point of view and with their own purposes in mind. Only one Etruscan book survives, a ritual calendar written on a bolt of woven linen that was recycled to wrap an Egyptian mummy. Combining artifacts, human remains, and foreign literature into a firm historical account is a fine art, and not easy to practice. It is also a frustrating art; a goodly proportion of what we now believe is almost certainly destined to be proven wrong. Mario Torelli, the chief curator of Gli Etruschi and editor of the catalog, has been one of the most accomplished practitioners ever to undertake the delicate task of reconstruction. Once a razor-sharp and provocative young scholar inspired by the charismatic Bianchi Bandinelli, he is now, although as witty as ever, a magisterial authority on Etruscan culture (like Giovanni Colonna, who writes one of the introductory essays here, and was himself the curator of a show associated with Buongiorno Etruschi in 1985, Santuari D’Etruria, “Sanctuaries of Etruria”5). The catalog that Torelli and his cohorts have assembled, appropriately for so irremediably speculative an undertaking, provides a variety of points of view in suggesting how to pin down the more elusive aspects of the ancient Etruscans’ lives and times.

Surprisingly, one of the most promising avenues of research presented here has to do with the most stubborn problem to beset Etruscan studies from the very beginning: the Etruscan language. The Etruscans borrowed their alphabet from the Greeks, who had just borrowed it from the Phoenicians, and the same writing system, against all odds, worked splendidly for all three tongues, despite their radically different structures. To match Phoenician letters to Etruscan sounds, some modifications had to be made to the alphabet—the Etruscans invented two letters of their own—but the letters themselves have been legible since the very end of the fifteenth century.

The problem has been to understand what the words themselves mean. Of the more than ten thousand Etruscan inscriptions that survive, only a few extend beyond a single line, and because they come almost exclusively from graves and votive offerings, we know next to nothing about the words the Etruscans used in their daily lives. Of the long inscriptions that survive, one has been discovered only recently, commemorating a division of property in the region of Cortona, and the relatively accessible aspects of its vocabulary and syntax have shed light on all the other extensive preserved inscriptions.

The Palazzo Grassi exhibition devotes one room to the Etruscan language, a display of inscriptions together with a soundtrack that presents various kinds of people, men, women, young, old, gravel-voiced, dulcet, reading the longer Etruscan texts, none of them much more exciting than a laundry list, and yet they are all that we have: “chief magistrate of Etruria” (zilath mechl rasnal), “September twenty-sixth, dedicate offerings to Neptune” (celi huthis zathrumis flerchva nethunsl sucri). Like Adso the novice at the end of Umberto Eco’s novel The Name of the Rose, we listeners seem to be chasing after the ashes of an incinerated library, gathering up the fragile scraps of thousands of manuscripts, and watching them disintegrate into powder in our hands. We have no Etruscan poetry, only pictures of Etruscans singing; no Etruscan histories, only Roman records of them; no Etruscan tragedies, only the Romans’ report of them, and of the still greater tragedy of Etruria’s eclipse.

Still, there are remnants of a language, and those remnants consistently reward the scrutiny that scholars have devoted to them. In their respective essays for the exhibition catalog, the senior scholar Carlo de Simone and his young colleagues Giovanna Bagnasco Gianni and Luciano Agostiniani, or Adriano Maggiani and Mauro Menichetti in the same catalog, do not entirely agree with one another on the meaning of such basic Etruscan words as å«spura, “city” (and I would see some of these words in a different way still), but for that very reason the way stands wide open for a discussion as lively as it has been in years.

Analysis of Etruscan contact with Greece tends to be filtered through a standard version of Etruscan history that traces the growth of an aristocratic society, customarily identified in these catalog entries as principes—princes—using a Latin word that was applied to Etruscan potentates by Roman historians. These princes in turn are supplanted in the sixth and fifth centuries BCE by a more egalitarian and increasingly urban society, for which the Greek word polis is repeatedly invoked and surely inappropriate; the Etruscan word å«spura seems to denote a different kind of entity altogether from a polis, as Stefan Steingräber’s essay in the catalog, “Etruscan Urban Planning,” suggests. The citizens of these å«spurer were led by entrepreneurial rulers like the legendary warlord Lars Porsenna or the archaeologically attested benefactor Thefarie Velianas, who sponsored the restoration of a seaside temple that melded into a single house of worship the cults of four nations: Phoenician Astarte, Greek Leukothea (the “White Goddess” of the seas), Etruscan Thesan (Dawn), and Latin Mater Matuta.

This account is based in part on an analogy with contemporary events in ancient Greece, where the literary and economic records are much more comprehensive and much more intelligible. It is also based partly on social and archaeological speculation, and partly, one might venture to say, on personal experience. It is tempting to see this tale of Etruria as also describing how an entrenched academic aristocracy has been replaced since World War II by a more egalitarian generation of scholars. It is also possible to trace something of the Marxist legacy of Bianchi Bandinelli in the way that, for example, a steep decline in the quality of certain kinds of Etruscan art can be traced to the change from a society of princes to a society characterized by a populous bourgeoisie; the advancement of the working classes is here presumed to compensate for any aesthetic decline.

It is useful to remember, however, that this standard account of Etruscan history—indeed, any account of Etruscan history—is based on slender evidence and remains open to legitimate question at almost every point; ancient history is a deliciously speculative enterprise rather than a secure one. And when questions about that enterprise become not only sharp but downright upsetting to the smooth progress of the traditional story, that is the time to pay closest attention.

The catalog of Gli Etruschi contains two instructive cases in point. Nearly all its essays on ancient art repeat the story of an Etruscan sculptor named Vulca of Veii, who came south to Rome in 509 BCE to supply terra-cotta statues for the new temple to Jupiter on the Capitoline Hill. In 1973, the German scholar Otto-Wilhelm von Vacano had already pointed out that Vulca’s identity depended entirely on how one read a garbled passage in the manuscripts of Pliny the Elder. In the nineteenth century, Vulca of Veii was thought to be named Turrianus of Fregellae—and there was, in fact, no way to make the Latin as written in the manuscripts make sense as it stood; careless copyists had irrevocably botched the text centuries before.6 Most scholars of Latin are not archaeologists, any more than most archaeologists are scholars of Latin; von Vacano wrote his explosive article in hopes of encouraging the two to talk to each other, but in fact they have not. Vulca carries on as if his right to legitimacy were beyond question, for if he totters or falls, so do a series of consequences to his existence: the dating of the temple sculptures from Veii, for example, which have been conveniently hooked to the date 510 BCE in order for them to furnish a basis for the reputation that resulted in Vulca’s summons to Rome.

The same web of preconception has hobbled interpretation of the largest Etruscan building yet discovered, the so-called palazzo unearthed on a desolate hill at Murlo south of Siena, the improbably named Poggio Le Civitate—“Hill of the Cities.”7 This site, because of its enigmatic name and a series of chance finds on the ground, had attracted Bianchi Bandinelli already in the 1930s; it was finally excavated by his young American protégé, Kyle Phillips, beginning in 1966.8 Phillips himself proposed that the building might have served as a political sanctuary, a kind of neutral sacred zone for a league of Etruscan cities that stood along the borders of several territories. Both the existence of such leagues and of at least one such political sanctuary, the Fanum Voltumnae, are described in Greek and Roman accounts of Etruria.

Almost immediately, however, Phillips’s Italian colleagues identified the building as an aristocratic palazzo, using a Renaissance term for a noble urban residence that has since come to signify an apartment building as well. Neither kind of palazzo bears any resemblance whatever to the isolated edifice of Poggio Le Civitate. Yet both Gli Etruschi and Haynes’s Etruscan Civilization enshrine this aristocratic palazzo as if it were a reality rather than a hypothetical construct; the impressive array of terra-cotta statues that crowned its roof is identified with blithe confidence in the catalog as images of ancestors, although they bear no marks of identification as such—or as anything else.9 Indeed, we have no means of knowing for certain what either building or statues were actually used for. It seems more constructive to call attention to our persistent uncertainty than to bury it deep under layers of conventional wisdom. Many an archaeological truth, after all, stands only one excavation away from demolition.

Besides, this very uncertainty can act as a wonderful stimulus for ingenuity: Stefan Steingräber’s essay on Etruscan urban planning and Maurizio Ha-rari’s bracing interpretation of later Etruscan pottery are models of how clear thinking and bold questions can combine with what we do know about Etruria to create visions hitherto unimagined of Etruscan times. The Etruscans are so deeply mysterious because we can never really know enough about them, and yet they reward us liberally nonetheless.

This Issue

July 5, 2001

-

1

On this issue the essay of Françoise-Hélène Massa-Pairault for The Etruscans is, characteristically, both learned and imaginative.

↩ -

2

See, for example, Ranuccio Bianchi Bandinelli, Storicità dell’arte classica (Florence: Sansoni, 1943, and subsequent editions); Etruschi e Italici prima del dominio di Roma (Milan: Rizzoli, 1973); Dal diario di un borghese, edited by Marcello Barbanera (Rome: Editori Riuniti, 1996.)

↩ -

3

The Augur’s Daughter was first published in German as Die Tochter des Augurs: aus dem Leben der Etrusker (Mainz am Rhein: Philipp von Zabern, 1981), and in English as The Augur’s Daughter (Rubicon, 1987). The catalog of the exhibition The Etruscans and Europe, edited by Massimo Pallottino, was published in French, German, Italian, and English editions in 1992.

↩ -

4

For a provocative look at the role clever eighteenth-century marketing has played in the appreciation of ancient Greek vase painting, see Michael Vickers and David Gill, Artful Craft: Ancient Greek Silverware and Pottery (Clarendon Press/Oxford University Press, 1994), especially Chapter One.

↩ -

5

Santuari D’Etruria, edited by Giovanni Colonna (Milan: Electa, 1985).

↩ -

6

Otto-Wilhelm von Vacano, “†Vulca, Rom und die Wölfin: Untersuchungen zur Kunst des frühen Rom,” Aufstieg und Niedergang der römischen Welt: Geschichte und Kultur Roms im Spiegel der neueren Forschung, I.4, edited by Hildegard Temporini (Berlin and New York: Walter de Gruyter, 1973), pp. 523–583.

↩ -

7

Although “Le Civitate” is the way that the site is attested in the great majority of documents going back to the fourteenth century in Sienese archives, it is usually called Poggio Civitate.

↩ -

8

See Kyle M. Phillips Jr., In the Hills of Tuscany: Recent Excavations at the Etruscan Site of Poggio Civitate (Murlo, Siena) (University Museum Publications/University of Pennsylvania Press, 1993).

↩ -

9

Torelli, The Etruscans, p. 587; but see Ingrid E.M. Edlund-Berry, The Seated and Standing Statue Akroteria from Poggio Civitate (Murlo) (Rome: Giorgio Bretschneider, 1992).

↩