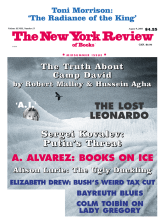

1.

Of the velvet-lined offering plates passed down the pews on Sunday, the last one was the smallest and the most nearly empty. Its position and size signaled the dutiful but limited expectations that characterized most everything in the Thirties. The coins, never bills, sprinkled there were mostly from children encouraged to give up their pennies and nickels for the charitable work so necessary for the redemption of Africa. Such a beautiful word, Africa. Unfortunately its seductive sound was riven by the complicated emotions with which the name was associated. Unlike starving China, Africa was both ours and theirs; us and other. A huge needy homeland none of us had seen or cared to see, inhabited by people with whom we maintained a delicate relationship of mutual ignorance and disdain, and with whom we shared a mythology of passive, traumatized otherness cultivated by textbooks, films, cartoons, and the hostile name-calling children learn to love.

World War II was over before I sampled fiction set in Africa. Often brilliant, always fascinating, these narratives elaborated on the very mythology that accompanied those velvet plates floating between the pews. For Joyce Cary, Elspeth Huxley, H. Rider Haggard, Africa was precisely what the missionary collection implied: a dark continent in desperate need of light. The light of Christianity, of civilization, of development. The light of charity switched on by simple human pity. It was an idea of Africa fraught with the assumptions of a complex intimacy coupled with an acknowledgment of profound estrangement. This combination of ownership and strangeness unfettered the imagination of fiction writers and, just as it had historians and explorers, enticed them into projecting a metaphysically void Africa ripe for invention.

Literary Africa—outside, notably, of the work of some white South African writers—was an inexhaustible playground for tourists and foreigners. In the novels and stories of Joseph Conrad, Isak Dinesen, Saul Bellow, Ernest Hemingway, whether imbued with or struggling against conventional Western views of benighted Africa, their protagonists found the continent to be as empty as the collection plate—a vessel waiting for whatever copper and silver imagination was pleased to place there. Accommodatingly mute, conveniently blank, Africa could be made to serve a wide variety of literary and/or ideological requirements: it could stand back as scenery for any exploit, or leap forward and obsess itself with the woes of any foreigner; it could contort itself into frightening malignant shapes in which Westerners could contemplate evil, or it could kneel and accept elementary lessons from its betters.

For those who made either the literal or the imaginative voyage, contact with Africa, its penetration, offered thrilling opportunities to experience life in its inchoate, formative state, the consequence of which experience was knowledge—a wisdom that confirmed the benefits of European proprietorship and, more importantly, enabled a self-revelation free of the responsibility of gathering overly much actual intelligence about African cultures. So big-hearted was this literary Africa, its invitation to explore the inner life was never burdened by an impolite demand for reciprocal generosity. A little geography, lots of climate, a few customs and anecdotes became the canvas upon which a portrait of a wiser or sadder or fully reconciled self could be painted.

In Western novels published up to and throughout the 1950s, Africa, while offering the occasion for knowledge, seemed to keep its own unknowableness intact. Very much like Marlow’s “white patch for a boy to dream over.” Mapped since his boyhood with “rivers and lakes and names, [it] had ceased to be a blank space of delightful mystery…. It had become a place of darkness.” What little could be known was enigmatic, repugnant, or hopelessly contradictory. Imaginary Africa was a cornucopia of imponderables that resisted explanation; riddles that defied solution; conflicts that not only did not need to be resolved, but needed to exist if the process of self-discovery was to have the widest range of play.

Thus the literature resounded with the clash of metaphors. As the original locus of the human race, Africa was ancient; yet, being under colonial control, it was also infantile. Thus it became a kind of old fetus always waiting to be born but confounding all midwives. In novel after novel, short story after short story, Africa was simultaneously innocent and corrupting, savage and pure, irrational and wise. It was raw matter out of which the writer was free to forge a template to examine desire and improve character. But what Africa never was was its own subject, as America has been for European writers, or England, France, or Spain for their American counterparts.

Even when Africa was ostensibly a subject, its people were oddly dehumanized in ways both pejorative and admiring. In Isak Dinesen’s recollections the stock of similes she draws on most frequently to describe the inhabitants belong to the animal world. “The old dark clear-eyed native of Africa, and the old dark clear-eyed elephant—they are alike.” The “hind part of a little old woman…is like a picture of an ostrich.” Groups of men are “herd[s] of sheep,” “old mules.” Masai finery is “stags’ antlers.” And in a moment meant to register the poignant heartache of leaving Africa, Dinesen writes of a woman as follows:

Advertisement

When we met she stood dead still, barring the path to me, staring at me in the exact manner of a Giraffe in a herd, that you will meet on the open plain, and which lives and feels and thinks in a manner unknowable to us. After a moment she broke out weeping, tears streaming over her face, like a cow that makes water on the plain before you.

In that racially charged context, being introduced in the early Sixties to the novels of Chinua Achebe, the work of Wole Soyinka, Ama Ata Aidoo, and Cyprian Ekwenski, to name a few, was more than a revelation—it was intellectually and aesthetically transforming. But coming upon Camara Laye’s Le Regard du roi in the English translation known as The Radiance of the King* was shocking. This extraordinary novel, first published in France in 1954 and in the US in 1971, accomplished something brand new. The clichéd journey into African darkness either to bring light or to find it is reimagined here. In fresh metaphorical and symbolical language, storybook Africa, as the site of therapeutic exploits or of sentimental initiations leading toward life’s diploma, is reinvented. Employing the idiom of the conqueror, using precisely the terminology of the dominant discourse on Africa, this extraordinary Guinean author plucked at the Western eye to prepare it to meet the “regard,” the “look,” the “gaze” of an African king.

If one is writing within and about an already “raced” milieu, advocacy and argument are irresistible. Rage against the soul murder embedded in the subject matter runs the risk of forcing the “raced” writer to choose among a limited array of strategies: documenting their seething; conscientiously, studiously avoiding it; struggling to control it; or, as in this instance, manipulating its heat. Animating its dross into a fine art of subversive potency. Like a blacksmith transforming a red-hot lump of iron into a worthy blade, Camara Laye exchanged African “enigma” and darkness for subtlety, for literary ambiguity. Eschewing argument by assertion, he claimed the right to intricacy, to nuance, to insinuation—claims which may have contributed to a persistent interpretation of the novel either as a simple race-inflected allegory or as dream-besotted mysticism.

2.

In his portrait of Africa, Camara Laye not only summoned a sophisticated, wholly African imagistic vocabulary in which to launch a discursive negotiation with the West, he exploited with technical finesse the very images that have served white writers for generations. Clarence, the protagonist, is a white European who has disembarked in an unnamed African country as an adventurer, one gathers. The filthy inn in the village where he is living could be taken word for word from Joyce Cary’s Mister Johnson; his susceptibility to and obsession with smells read like a play upon Elspeth Huxley’s The Flame Trees of Thika; his European fixation with the “meaning” of nakedness recalls H. Rider Haggard or Joseph Conrad or virtually all travel writing. Reworking the hobbled idioms of imperialism, colonialism, and racism, Camara Laye allows us the novel experience of both being and watching an anonymous interloper discover not a new version of himself via a country waiting for Western imagination to bring it into view, but an Africa already idea-ed, gazing upon the Other.

It is not made clear what compels Clarence’s journey. He is not on a mission, or a game hunt, nor does he claim to be exhausted by the pressures of Western civilization. Yet his desire to penetrate Africa is urgent enough to risk drowning. “Twenty times” the tide has carried his boat toward and away from the shore. Quite deliberately and significantly, Camara Laye spends no time describing Clarence’s past or his motives for traveling to Africa. He can forgo with confidence a novelist’s obligation to provide background material and rely on the conventions of white-man-in-Africa narratives wherein the reason for the quest is itself a prickly question since it often involves less than innocent impulses. In Saul Bellow’s Henderson the Rain King one chapter opens, “What made me take this trip to Africa? There is no quick explanation”; and another, “And now a few words about my reasons for going to Africa.” The answer, forthrightly, is desire: “I want, I want, I want.”

Conrad’s characters are driven to Africa by passionate curiosity or else assigned, as it were. One way or another we are to believe they have as little choice to make the trip as the indigenous people have to receive them. Hemingway, even as he experiences the continent (empty except for game and servants) as his private preserve, allows his characters to imply the question and hazard emotional answers. “Africa was where Harry had been happiest in the good times of his life, so he had come out here to start again.” “Africa cleans out your liver,” Robert Wilson tells Francis Macomber, “burns fat from the soul.” Clarence, too, posits the question repeatedly. “‘Why did I want to cross that reef at all costs?’ he wondered. ‘Could I not have stayed where I was?’ But stay where?…on the boat? Boats are only transitory dwellings!… ‘I might have thrown myself overboard,’ he thought. But wasn’t that exactly what he had done?” “‘Can that [life beyond death] be the sort of life I have come here to find?'” Whatever the answer, we never expect what Camara Laye offers: an Africa answering back.

Advertisement

Clarence’s immediate circumstance is that he has gambled, lost, and, heavily in debt to his white compatriots, is hiding among the indigenous population in a dirty inn. Already evicted from the colonists’ hotel, about to be evicted by the African innkeeper, Clarence’s solution to his pennilessness (with the habitual gambler’s insouciance) is to be taken into “the service of the king.” He has no skills or qualities, but he has one asset that always works, can only work, in third-world countries. He is white, he says, and therefore suited in some ineffable way to be adviser to a king he has never seen, in a country he does not know, among people he neither understands nor wishes to.

His sense of entitlement, however, is muted by timidity and absence of esteem, “having lost the right—the right or the luxury—to be angry.” He is prevented by a solid crowd of villagers from speaking to the king, but after a glimpse of him from afar, he is resolute. He meets a pair of mischief-loving teenagers and a cunning beggar who agree to help him out of his difficulty with the innkeeper and the surreal trial for debt that follows. Under their hand-holding guidance he travels south, where the king is expected to appear next. What begins as a quest for paid employment, for escape from the contempt of his white countrymen and unfair imprisonment in an African jail, could easily have become a novel about another desperate Westerner’s attempt to reinvent himself. But Camara Laye’s project is different: to investigate cultural perception and the manner in which knowledge arrives. The episodes that Clarence confronts trace and parody the parallel sensibilities of Europe and Africa. Different notions of status, civitas, custom, commerce, and intelligence; of law or of law versus morality—all are engaged here in a nuanced dialogue; in scenes of raucous misunderstandings; in resonant encounters with “mythic” Africa.

Challenging the cliché of Africa as sensual and irrational, Camara Laye uses an “inferno of the senses” as a direct route to rationality. What Clarence sees first as dancers “freely improvis[ing], each without paying any attention to his companions,” and doing what he believes are “war dances,” a “barbaric spectacle,” turns out to be dancers performing an intricate choreography in the shape of a star as they surround the king. Village huts that appear to him originally as monotonous, slipshod hovels he sees later as

magnificent pottery…the walls… smooth and sonorous as drums or deep bells, delicately, delightfully varnished and patinated, with the good smell of warm brick…. Windows like portholes had been let into the walls, just big enough to frame a face, yet not so big that any passing stranger could cast more than a swift glance into the interior of the hut…. Everything was perfectly clean: the roofs were newly thatched, the pottery shone as if it had been freshly polished.

Clarence hears indigenous music as “utterly without meaning”; “queer haphazard noise.” In the forest that he finds “absolutely still,” “completely empty,” his companions hear drums announcing not just their arrival but who, specifically, is arriving. The overpowering, repugnant “odor of warm wool and oil, a herdlike odor,” becomes “a subtle combination of flower-perfumes and the exhalations of vegetable molds…a sweetish, heady, and disturbing odor…all-enveloping rather than repellent…caressing…alluring,” and, one might add, addictive. Once he arrives where the king is expected to appear, he is touched, fondled, and spends his nights steeped in carnal pleasures. The author orchestrates the senses as conduits that make information and intelligence available.

Principally, however, the novel focuses its attention on the authority of the gaze. Sight, blindness, shadows, myopia, astigmatism, delusion are the narrative figurations which lead Clarence and the reader to the novel’s dazzling epiphany at the end of his journey, when the king turns to face him. Ignorance and lack of insight are signaled by melting horizons, shifting architecture, torpor. People and events require his and our constant revision. Although it is Clarence’s wish for oblivion, to “sleep until the day of deliverance,” until he can “catch the king’s eye,” information is all around him if he chooses to gather it. But Clarence looks away from faces, eyes. His habit of staring at the beggar’s Adam’s apple rather than his eyes costs him dearly. When, finally, he does look, “he thought he saw in them a dishonest look, a kind of irony, too, and perhaps both of these…. Something sly, insidious?… Something faintly mocking? How could one tell?” When women appear he sees only their “luxuriant buttocks and breasts.” Even the African woman he lives with is “no different from the others”:

Akissi would put her face in the porthole’s oval frame, and Clarence would be able to recognize it as hers. But as soon as he saw her whole body, it was as if he could no longer see her face: all he had eyes for were her buttocks and her breasts—the same high, firm buttocks and the same pear-shaped breasts as the other women….

Clarence is enslaved, but he refuses to understand the negotiations for his bondage even though they take place in his presence. In his estimation, the conversations following the beggar’s proposal to sell him to service the harem of the Noga, the chief of the village, are merely trivial or simply opaque; all subsequent hints of his services he dismisses as babble. When the “mystery” of his bondage becomes so blatant that perception is inescapable, he greets the perception with unease and lame, truncated questions, without genuine curiosity. Even as he gains rank in the village—now that he is of use—and pointed comments mount, he hides behind his innocence. “Felt all over like a chicken on market-day” by the obese eunuch Samba Baloum, Clarence is merely offended by the familiarity, unaware that a deal has been struck. Because African laughter is senseless to him, he never gets the joke or recognizes double-entendre. Dreams loaded with valuable information he finds “silly.” Frequently disguised as a dream, disorientation, or confusion, events and encounters designed to invite perception accumulate as Clarence’s Western eye gradually undergoes transformation. “Clarence was now perfectly aware that he had been dreaming; but he could also see now that his dream was true.”

What counts as intelligence here is the ability and willingness to see, surmise, understand. Clarence’s confusion is deeply confusing to those around him. His refusal to analyze or meditate on any event except the ones that concern his comfort or survival dooms him to servitude. When knowledge finally seeps through, he feels “annihilated” by it. Stripped of the hope of interpreting Africa to Africans and deprived of the responsibility of translating Africa to Westerners, Clarence provides us with an unprecedented sight: a male European, de-raced and de-cultured, experiencing Africa without resources, authority, or command. Because it is he who is marginal, ignored, superfluous; he whose name is never uttered until he is “owned”; he who is without history or representation; he who is sold and exploited for the benefit of a presiding family, a shrewd entrepreneur, a local regime; we observe an African culture being its own subject, initiating its own commentary.

3.

Clarence does indeed find “the life which lies beyond death,” but not before a reeducation process much like Camara Laye’s own cultural education in Paris. Born on the first day of 1928 to an ancient Malinke family in Guinea, Camara Laye attended a Koranic school, a government school, and a technical college in Conakry. Awarded a scholarship at the age of nineteen, he left for France in 1947 to study automobile engineering. Memories of the solitude, poverty, and menial labor that were his lot in Paris became the genesis of his first book, the autobiographical L’Enfant noir (1953), praised and prized in France. Deep admiration for French art and culture did not rival his fervent love of his own.

He entered the political climate of postcolonial Guinea and the strife-ridden relationship between France and Francophone West Africa with the conviction that “the man of letters should contribute his writing to the revolution.” His proud commitment to this blend of art and politics, freedom and responsibility, had serious and damaging consequences: imprisonment by Sékou Touré, exile under the protection of Léopold Senghor in Senegal, and a constantly imperiled existence. Notwithstanding the usual menu of cultural/educational/government posts offered to writers, the trials of exile, and debilitating bouts of illness, Camara Laye lectured, wrote plays, journalism, and, in 1966, twelve years after the publication of Le Regard du roi, completed Dramouss (translated as A Dream of Africa). Le Maître de la parole (The Guardian of the Word) appeared in 1978. Full of plans for future projects, Camara Laye succumbed to illness and, in 1980, died at the age of fifty-two.

Camara Laye described L’Enfant noir—the story of his rural childhood, his education in Guinea’s capital and later in Paris—as “what I am.” Dramouss continues the “what I am” project, keeping close to the author’s own life. In this novel a narrator returns to Guinea, where he finds “a regime of anarchy and dictatorship, a regime of violence”—words understood to have provoked Sékou Touré. Camara Laye was never to write as overtly politically again, but Le Maître de la parole charts the life of the first emperor of the Kingdom of Mali as told by griots, and can be read as a comment on contemporary African politics.

The autobiographical groove Camara Laye settled into was violently disrupted just once. Le Regard du roi is his only true fiction. To grasp the force of his talent as a novelist and to fully appreciate the singularity of his project, it is important to be alert to the cultural snares that entangle critical discourse about Africa. Shreds of the prejudices that menace Clarence cling to much of the novel’s appraisal. In its explications, the language of criticism applied to Laye’s fiction favors “spontaneous wisdom” rather than strategy; spirit as distinct from the visible, comprehensible world; “mute symbols and cryptic messages” over modern complexity; a naturalistic, universal humanism valued as a “gift to white readers” over craftsmanship. Less attention is given to the book’s pregnant dialogue; its delicate, almost clandestine, pacing; its carefully governed structure; to how the author’s imagery deflates, alters, and addresses certain foundational European values; to his brilliant exploration of the concept of individual rights, the preeminence of money, and the bewildering obsession with the naked body.

Of the many literary tropes of Africa, three are invidious: Africa as jungle—impenetrable, chaotic, and threatening; Africa as sensual but not on its own rational; and the essence or “heart” of Africa, its ultimate discovery, as, unless mitigated by European influence and education, incomprehensible. The Radiance of the King makes these assessments concrete in such a way as to invite (not tell) the reader to reevaluate his or her own store of “knowledge.”

It is fascinating to observe Camara Laye’s adroit handling of certain elements of this mindscape. Impenetrable Africa. Clarence is afraid of the forest, seeing it as a wall, very much like the palace wall that appears to have no entrances, and as unnavigable as the maze of rooms through which he must make his escape. Because his trust in his companions is justifiably limited, he enters the forest with trepidation. What he does not trust at all is his own sight. Although his companions exhibit no confusion, Clarence’s fear is stupefying. In spite of noting that the forests are “devoted to wine industry,” that the landscape is “cultivated,” that the people living there give him a “cordial welcome,” Clarence sees only inaccessibility, “common hostility,” a vertigo of tunnels, invisible paths barred by thorn hedges. The order and clarity of the landscape are at odds with the menacing jungle in Clarence’s head. “Where are the paths?” he cries. “There are paths,” the beggar answers. “If you can’t see them…you’ve only got your own eyes to blame.”

Sensual Africa. Clarence’s descent into acquiescent stud is a wry comment on the sensual basking that Europeans found so threatening. He enacts the full horror of what Westerners imagine as “going native,” the “unclean and cloying weakness” that imperils masculinity. But Clarence’s overt enjoyment of and feminine submission to continuous cohabitation reflect less the “dangers” of sexy Africa than the exposure of his willful blindness to a practical (albeit loathsome) enterprise. The night visits of the harem women (whom Clarence continues to believe against all evidence are one woman) are arranged by the nobu, an impotent old man, for the increase of his family rather than for Clarence’s indulgence. The deceit is an achievement made possible by the Africans’ quick understanding of this Frenchman’s intellectual indolence, his tendency toward self-delusion. As mulatto children crowd the harem, Clarence, the only white in the region, continues to wonder where they came from.

Dark Africa. Although the novel is a revision of the white man’s voyage into darkness, I do not see the journey, as some readers do, as a progression from European adult corruption to African childlike purity. Nor do the trials Clarence undergoes seem to imitate an Everyman’s pilgrimage through sin and self-loathing necessary in order to effect an ultimate baptism. It appears to me that Clarence’s voyage is from the metaphorical darkness of immaturity and degradation. Both of these crippling states precede his entrance into the narrative and are clearly dramatized by the adolescent stupidity with which he handles his affairs and the humiliation he has already suffered at the hands of his European compatriots. Camara Laye’s Africa is suffused with light: the watery green light of the forest; the blood-red tints of the houses and soil; the sky’s “unbearable…azure brilliance”; even the scales of the fish-women he sees glimmer “like robes of dying moonlight.”

The king’s youth and Clarence’s nakedness may encourage the reading of this novel as culminating with an inner child craving and receiving unearned yet limitless love. But the nakedness Clarence insists upon at the end is neither childish nor erotic. Nor is it “shamelessly immodest.” It is stark, absolute—like a truth. “‘Because of your very nakedness!’ the [king’s] look seemed to say.” He is accepted, loved, and called into view by the royal gaze because he has arrived at the juncture where truth, knowledge, is possible for him; where the “terrifying void that is within [him]…opens to receive [the king].”

This openness, the crumbling of cultural armor and the evaporation of ego, is the beginning of an adult knowledge which is, of course, Clarence’s salvation and his bliss. But deep in the heart of Africa’s Africa is more than the restorative gaze of the king. There at its core is also equipoise—the radiance of his exquisite articulation: “Did you not know that I was waiting for you?”

This Issue

August 9, 2001

-

*

This essay appears in different form as the introduction to a new edition of the novel, just published by New York Review Books.

↩