1.

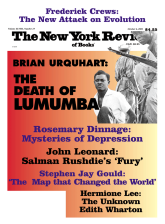

Patrice Lumumba, the first prime minister of the independent state of the Congo, was in power for only twelve weeks, but he has become a legend—to some a saint and martyr, to others a psychotic demagogue. Recently several books, a film, and a Belgian painter, Luc Tuymans, have portrayed Lumumba as a defining figure of his time, a heroic victim of Western greed, prejudice, and brutality. Detailed revelations about his death have, in terrible detail, filled in the gaps in previous accounts.

The tragedy of Lumumba touches on, and sometimes illuminates, many historical themes—colonialism and neocolonialism; African decolonization and the problems of transition and leadership; the influence of great international corporations; the cold war’s disastrous effect on parts of Africa during the liberation period; the limitations of the UN’s peacekeeping role; and, not least, the creation of myths and legends.

Belgium’s exploitation of the Congo was the darkest episode in all the murky history of European colonialism. To feed King Leopold II’s manic appetite for ivory and rubber, mutilations, mass executions, and the use of the chicotte—a hippopotamus hide whip that cut through skin and muscle—administered by the indigenous Force Publique commanded by Belgian officers had halved the population within a few years and left a legacy of oppression and cruelty that poisoned forever the relations of Congolese and Belgians.

At the Congo’s independence on June 30, 1960, the young King Baudoin, in a paternalistic speech, praised his ghastly ancestor’s achievements. Lumumba’s fiery response brought into the open the latent rage and resentment of his people. Perhaps for the first time, Belgian officials realized that after independence, with Patrice Lumumba as prime minister, things would not, as they had hoped, go on much as before.1

The Congo, unlike most African colonies, had no longstanding liberation movement either at home or abroad, or any internationally recognized independence leaders like Mandela, Kenyatta, Nkrumah, Nkomo, Nujoma, and others. Such liberationist activity as there was had been sanctioned only in 1957 and was led by Joseph Kasa Vubu, who was to become the Congo’s first president. Lumumba, a former postal clerk and beer salesman, became the leader of the nationalist, supratribal party, the Mouvement National Congolais, in Stanleyville, his political base. He was arrested for the first time in November 1959 and then released to take part in the Brussels Roundtable that set the scene for the Congo’s suddenly accelerated independence, precipitated in part by Charles De Gaulle’s abrupt granting of independence to France’s African colonies. Congolese independence was in every way a last-minute arrangement.

Whether because they believed that independence would be little more than a formality or because of the superiority and contempt they felt for their unfortunate African subjects, the Belgians, unlike other colonial powers, made no practical arrangements for an independent Congo. No Congolese had ever taken part in the business of government or public administration at any important level. Only seventeen out of a population of 13.5 million had university degrees. There was not one Congolese officer in the Force Publique, which was to become the Armée Nationale Congolaise (ANC). No colony had ever faced independence so ill-prepared.

Events in the first days of independence went at a diz- zying pace. The army mutinied and threw out its Belgian officers. Europeans were roughed up, and there were reports of white women being raped. The Belgian population panicked and left. Belgian paratroopers were deployed to protect the remaining Europeans. These troops, believed by the Congolese to have been sent to reverse independence, clashed with the soldiers of the ANC—which had no officers—in the major cities. With the connivance of Belgium, the richest province, Katanga, whose president was Moise Tshombe, seceded from the new republic. Public administration, law, and order evaporated and were replaced by chaos and anarchy.

President Kasa Vubu and Prime Minister Lumumba were, understandably enough, unable to stem this tidal wave of misfortune and appealed to the United Nations for help. The UN secretary-general, Dag Hammarskjöld, brought their request to the Security Council, which on July 14, despite the reservations of Belgium’s NATO allies, the United States, France, and Britain, called on Belgium to withdraw its troops from the Congo. The Council also authorized the secretary-general to provide the Congo government with such military assistance as was necessary until its national security forces were able to meet their tasks fully. The American UN undersecretary, Ralph Bunche, already in Léopoldville and soon to become the head of the UN mission, tried to explain the nature and limitations of the UN operation in his talks with Kasa Vubu and Lumumba. The UN troops could, he told them, only use force in self-defense and could not be used to influence the outcome of any internal conflict.2

Advertisement

The first UN troops, from Morocco, Ghana, Ethiopia, and Tunisia, arrived two days after the Security Council decision, and within ten days ten thousand soldiers, initially all from African countries, were deployed throughout the country except in Katanga. A military training mission under a Moroccan officer, General Ben Hammou Kettani, was set up to train and reorganize the ANC. The UN also organized a large civilian task force to run the abandoned public services—communications, central bank, airfields, police, hospitals, etc.—and to train the Congolese to take them over.

It soon became clear that Lumumba was not going to be an easy person to help. His dealings with the UN quickly deteriorated into a bewildering series of pleas for assistance, threats, and ultimatums. He issued impossible demands and expected instant results. He made urgent requests for protection, punctuated by accusations that the UN was collaborating with the Belgians. In fact the UN mission was daily struggling with the Belgians in an effort, ultimately successful, to get their troops out of the Congo.

After the Belgian troops had left the rest of the Congo, the secession of Katanga became the new government’s primary obsession. Lumumba refused to understand that under their mandate, the UN peacekeepers could not reverse the Katanga secession by force and would have to deal with it by other, less dramatic means. Hammarskjöld was convinced that war between the various parties in the Congo would only turn a bad situation into a catastrophe. “I do not believe, personally,” he told the Security Council in reply to a Soviet demand that the UN troops should use force to annul the Katanga secession, “that we help the Congolese people by actions in which Africans kill Africans, or Congolese kill Congolese, and that will remain my guiding principle in the future.”

In mid-August Hammarskjöld took the considerable risk of personally leading the first UN troops into Katanga to provide the basis for the withdrawal of Belgian troops, as had been done successfully in the rest of the country. He did not take Lumumba with him on this already hazardous venture; the prevailing hatred and fear of Lumumba in Katanga would almost certainly have ensured a violent and bloody end of the mission, and probably of Lumumba and Hammarskjöld as well.

This kind of pragmatism was lost on Lumumba, and, resenting his exclusion from the Katanga venture, he violently attacked Hammar- skjöld and the UN mission, his words being faithfully parroted by his new ally, the Soviet Union. He also refused to meet with Ralph Bunche, the head of the UN operation.3 Bunche, who considered that access to the prime minister was vital to the UN’s mission, asked to be replaced by someone with whom Lumumba would be willing to deal.

Far more disastrous, Lumumba dispatched units of the ANC, untrained and without logistics or leadership, in an attempt to deal by force both with Katanga and with a nascent secessionist movement in neighboring Kasai. He appealed for Soviet support in this desperate venture, and was given trucks, advisers, and ten transport planes. The planes and advisers were quickly withdrawn when the situation became too dangerous, but not before they had helped the ANC to massacre more than a thousand of Kasai’s Luba people.

Lumumba had visited Washington in July and talked with Secretary of State Christian Herter and Undersecretary of State Douglas Dillon. According to Dillon, Lumumba impressed both men as an irrational, almost “psychotic” personality, and the willingness of the United States government to work with him began to evaporate.4 Lumumba’s rejection of the UN and his call for Soviet military aid confirmed Washington’s worst fears of a Soviet takeover in the Congo, with Lumumba as an African Fidel Castro. As a US Senate inquiry later showed, the Eisenhower administration authorized the prime minister’s assassination.5

The bloody fiasco in Kasai aroused even the placid President Kasa Vubu to action. With the encouragement of Belgium and the United States, he dismissed Lumumba for governing arbitrarily and plunging the country into civil war. Half an hour later Lumumba declared on the radio that Kasa Vubu was no longer chief of state and he called upon the people to rise up and the army to die with him. The Western nations sided with Kasa Vubu, the Soviet bloc with Lumumba, and the UN operation was caught in the middle. As Bunche’s successor, Rajeshwar Dayal, put it,

The UN is here to help but not to intervene, to advise but not to order, to conciliate but not to take sides…. We have refused to take any position if it could only remotely be considered as an act of intervention. But how can the duty of maintaining law and order be discharged without taking specific action when necessary? That is the problem that faces us daily and which is yet to be solved.

All sides—Belgium, the United States, the Soviets, Lumumba, and Joseph Mobutu, Lumumba’s military aide—loudly criticized the UN, a foretaste of Bosnia thirty years later, where the UN’s much-despised neutrality and impartiality in a controversial conflict pleased no one.

Advertisement

On the evening of September 14, Joseph Mobutu—who had suddenly and unexpectedly broken with Lumumba and was establishing a power base of his own in alliance with Kasa Vubu—announced over the radio that he was “neutralizing” the chief of state, the two rival governments, and the parliament until the end of the year. In the meantime, he said, he would call in “technicians” to run the country. For his part Lumumba threatened that in eight days’ time Soviet troops would come to the Congo, as the English translation puts it, “…in order to brutally expel the UN from our Republic…. If it is necessary to call on the devil to save the country, I will do it without hesitation, confident that with the total support of the Soviets, I will, in spite of everything, emerge victorious.”6 Four days later, in a complete about-face, Lumumba sent Hammarskjöld a reconciliation agreement with Kasa Vubu “which effectively puts an end to the Congolese crisis.” In it he asked for full UN assistance and assured the secretary-general of his full cooperation.

To the fury of the United States and its Western allies, Hammarskjöld refused to recognize Mobutu and announced that the UN’s objectives should be to reconcile Lumumba and Kasa Vubu, to restore constitutionality, to reopen the parliament, and to get the government to tackle the now catastrophic internal situation—an empty treasury and the breakdown of public administration, judiciary, tax collection, and functioning schools.

Lumumba was being guarded by UN troops in his official residence, and Hammarskjöld refused to allow his arrest, which the US ambassador in Léopoldville had been urging on Kasa Vubu and Mobutu.7 Washington threatened to withdraw US support from the UN Congo operation, and in November, against Hammarskjöld’s strongly expressed advice, the United States succeeded in getting the UN General Assembly to recognize the Kasa Vubu/Mobutu regime.

After the assembly decision, Lumumba, now increasingly isolated in his UN-guarded residence, with an outer ring of Mobutu’s troops waiting to pounce on him, decided to leave Léopoldville for Stanleyville, his home base. During a tropical downpour, as Kasa Vubu was celebrating his recognition by the UN General Assembly with a lavish dinner party, Lumumba, hidden in the back of a car, secretly left his residence and headed for Stanleyville.

Lumumba had been told repeatedly by UN officials that if he left his residence in Léopoldville it would be at his own risk and responsibility. In accordance with the UN’s policy of noninterference in internal affairs, the chief of the UN operation, Rajeshwar Dayal, gave orders that UN troops across the country should not interfere either with Lumumba’s movements or with those of his pursuers. Mobutu’s soldiers finally caught up with Lumumba at Mweka in Kasai and flew him back to Léopoldville where he was seen, bound and disheveled, before being imprisoned with his two companions. Hammarskjöld’s demands that Lumumba be treated with the respect due to a prime minister and member of parliament and given a fair hearing were ignored.

Even behind bars Lumumba made his captors nervous, and they decided to transfer him secretly to a place where he was sure to be killed. Their first choice was Kasai, where the Luba leader, Albert Kalonji, had vowed to make Lumumba’s skull into a flower vase. When, at the last minute, they found that UN troops were stationed on Kasai’s Bakwanga airfield, Kasa Vubu told the initially resistant Tshombe that Lumumba would be sent to Katanga. His Belgian handlers soon convinced Tshombe to go along with the plan, and Lumumba, after six hours of savage beating in the plane by Luba guards, was dumped on the tarmac in Elisabethville.

2.

Raoul Peck’s film Lumumba and Ludo De Witte’s The Assassination of Lumumba both give graphic accounts of Lumumba’s gruesome death, based on De Witte’s research in the Belgian archives and on many interviews with those involved. Although the Belgians attempted to pin responsibility for the assassination on the Congolese—“a Bantu affair”—they had, according to De Witte, conceived the plan, and Belgian officers and officials were pres-ent throughout Lumumba’s last hours. Their intentions, and Lumumba’s transfer, had of course been carefully concealed from the United Nations.

After Lumumba and his two companions were dumped, bloody and disheveled, in a remote corner of the Elisabethville airfield, they were beaten again with rifle butts, and thrown onto a jeep and driven two miles from the airport to an empty house in the bush, where a veteran Belgian officer, Captain Julien Gat, took charge. A series of visitors—the notorious Katangese interior minister Godefroid Munongo and other ministers, Tshombe himself, and various high-ranking Belgians—came to the house to gloat over the prisoners, who were again beaten. Some of the Belgian visitors later spoke of Lumumba’s courage and dignity under this treatment, but none saw fit to stop it. The soldiers were ordered to kill Lumumba if UN troops located the house.

During the evening, drinking heavily, Tshombe and his ministers decided that the three should be executed at once. Around 9:30 PM the inebriated Katangese ministers returned to the house in the bush. After once again being beaten up, the prisoners were stuffed into a car with Captain Gat and police commissioner Frans Verscheure, and, in a convoy that also carried Tshombe, Munongo, and four other “ministers,” were driven at high speed to a remote clearing fifty kilometers out in the wooded savanna. Joseph Okito, the former vice-president of the Senate, was the first to face the firing squad; next came Maurice Mpolo, the first commander of the Congolese National Army; and finally Patrice Lumumba. Their corpses were thrown into hastily dug graves.

This was not the end of the atrocious affair. During the night, the Belgians, increasingly apprehensive, began to concoct an elaborate cover plan under which Lumumba and his companions had been well treated, but had later managed to escape and had been killed by the inhabitants of an unnamed “patriotic” village. The Belgians also decided that the corpses must disappear once and for all. Two Belgians and their African assistants, in a truck carrying demijohns of sulphuric acid, an empty two-hundred-liter barrel, and a hacksaw, dug up the corpses, cut them into pieces, and threw them into the barrel of sulphuric acid. When the supply of acid ran out, they tried burning the remains. The skulls were ground up and the bones and teeth scattered during the return journey. The task proved so disgusting and so arduous that both Belgians had to get drunk in order to complete it, but in the end no trace was left of Patrice Lumumba and his companions. Lumumba was thirty-six years old.

3.

Raoul Peck has recreated Patrice Lumumba’s brief and tumultuous public career in a remarkable movie. His wonderful actors, especially Eriq Ebouaney as Lumumba and Alex Descas as Mobutu, portray the principals in a way that is both moving and convincing. His European cast, particularly Rudi Delhem as the Belgian commander, General Janssens, convey brilliantly the Belgian attitude—arrogant, patronizing, obstinate, but increasingly querulous and nervous—which had so much to do with the tragic debacle of the Congo’s independence.

Peck gives a lively impression of the confusions and rivalries on the Congolese side, and of the gulf between Kasa Vubu’s passive postcolonial tribal federalism and Lumumba’s dream of a national state that transcended both colonialism and tribalism. Lumumba is presented as a great hero, but Peck also hints at the frenetic atmosphere that he created, and the fears, conspiracies, and hatreds that flourished around him. Lumumba’s speech to the parliament after Mobutu’s coup shows movingly the oratorical—some would call it demagogic—flair that made his rivals and enemies so fearful of him. Peck’s film, shot in Zambia, Mozambique, and Belgium, conveys a strong physical impression of the Africa where the tragedy unfolds—its vastness, loneliness, and melancholy beauty, and the pulsing life of its cities.

In his book The Assassination of Lumumba, De Witte has performed an important service in establishing the appalling facts of Lumumba’s last days and Belgium’s responsibility for what happened. As a result of his book the Belgian parliament has set up a commission of inquiry, and it will be interesting to see what its response will be.

The ideological setting in which De Witte frames his findings is less convincing. De Witte proclaims that what happened in the Congo in 1960 was “a staggering example of what the Western ruling classes are capable of when their vital interests are threatened.” He dumps Belgium, the Western Europeans, the United States, and the United Nations into this capacious ideological basket. He claims that they engaged in a vast neocolonialist conspiracy to negate Congolese independence and the revolutionary promise of Lumumba, whose selfless “vision of creating a unified nation state and an economy serving the needs of the people” would have been an insurmountable obstacle to their neocolonialist plans. While this thesis may have some validity when it comes to the Belgian government of the time and the multinational corporations that exploited the Congo’s phenomenal natural wealth, it is seriously misconceived with respect to the United States, and ridiculous when applied to the United Nations. It also omits Lumumba’s own calamitous contribution to the confusion, violence, fear, and hostility that blasted the early hopes of the Congo’s independence.

During and after World War II, the United States, to the consternation of its main European allies, took the lead in establishing decolonization as a primary objective of the allied war effort. The process, with the United Nations as a catalyst, went much faster than had been expected. What was not foreseen was that in some African states cold war rivalries would turn decolonization into a nightmare—a nightmare from which a country like Angola has yet to awaken.

In July 1960, both the United States and the Soviet Union were keenly interested in the future of the newly independent Congo, the third-largest and, in natural resources, the richest former colony in Africa. The size and activity of the Soviet embassy in Léopoldville particularly alarmed Washington. Lumumba’s visit to Washington in July 1960 went badly, and a month later his rejection of the UN and appeal to the Soviet Union for military assistance confirmed the Eisenhower administration’s worst fears. The consequent authorization by the Eisenhower administration of the CIA to assassinate Lumumba, an elected prime minister, was an outrageous, almost hysterical, decision, fortunately frustrated by the UN troops protecting Lumumba’s residence and by a lack of enthusiasm among CIA field officers for using poisoned toothbrushes and other equally loony devices for eliminating Lumumba.8

Washington supported both Kasa Vubu’s dismissal of Lumumba and Mobutu’s coup, and strongly criticized Hammarskjöld and the UN mission for protecting Lumumba and refusing to recognize Mobutu. The obsession of the US with the cold war, not neocolonialism, accounted for the outlandishness of United States Congo policy. And talking of neocolonialism, would a Soviet takeover in the Congo and its active support for the wars that Lumumba seemed to think were the only way to deal with his opponents really have been such a blessing for the Congo and for Africa?

De Witte claims that the UN, and specifically Dag Hammarskjöld, was part of the neocolonial conspiracy, or, as Nikita Khrushchev told the UN General Assembly in a violent attack on the “colonialists,” “…They have been doing their dirty work in the Congo through the Secretary-General of the United Nations and his staff….” It is odd to find the straight Soviet line regurgitated by De Witte in such pristine condition forty years later. He even solemnly repeats the old Soviet canard about the “Congo Club,” “a group of senior UN officials intent on making sure that the international organization safeguarded Western interests in the Congo.”9

If De Witte’s reading of the UN archives had been less selective, he might have noticed that Hammarskjöld’s major confrontations were as much, or more, with the Belgians and the United States as with the Soviets. Hammarskjöld had expected the Belgians to be obstructive, and they exceeded his expectations at every turn. However, his main preoccupation was to keep the cold war out of the Congo (and Africa), and he saw this as one of the main purposes of the UN operation.10This was why he, and many others, regarded Lumumba’s appeal for Soviet military aid as the height of irresponsibility.

De Witte claims that the UN was, from the outset, opposed to Lumumba. As one of the UN officials who took part, during those tense early months in Léopoldville, in the seemingly interminable struggle with the Belgians and in our frequent and heated disagreements with the ambassadors of the United States and Britain, I find this puzzling. The UN was pledged to assist the new government, but not in military adventures that were neither wise, nor permitted by its mandate, nor feasible in view of its limited strength and armament.

De Witte, excoriating Hammarskjöld for refusing to use force to squash secessionist Katanga, writes that “Hammarskjöld…had a huge intervention force in the Congo.” This blatantly misleading sentence describes exactly what the UN force in the Congo was not. It was not Hammarskjöld’s personal plaything but a mission authorized and supervised by the UN Security Council. At the time, the UN force numbered some 16,000 lightly armed troops deployed in small detachments throughout a country the size of Western Europe. (The present NATO force in Kosovo has 42,500 heavily armed troops in a country smaller than Connecticut.) The UN force was precisely the opposite of an “intervention force.” It was expressly forbidden by the Security Council to intervene in internal conflicts, and only in February 1961, after Lumumba’s death, did the Security Council extend the UN’s authority to use force to stopping civil war and to dealing with foreign mercenaries—scarcely a broad military mandate even then. Such flagrant and deliberate misstatements in support of a flawed ideological thesis do nothing for De Witte’s credibility.

4.

Patrice Lumumba’s assassination was an unpardonable, cowardly, and disgustingly brutal act. Belgium, Kasa Vubu and Mobutu, and Moise Tshombe bear the main responsibility for this atrocity. The United States, and possibly other Western powers as well, tacitly favored it and did nothing to stop it.

Nor, in view of what subsequently happened, can the United Nations escape responsibility. After protecting Lumumba for two months in his official residence in Léopoldville, it stuck rigidly to its policy of noninterference in internal political conflicts after he left secretly for Stanleyville. In refusing to help or hinder either Lumumba or the Kasa Vubu/Mobutu regime (now recognized by the UN General Assembly), the UN force missed, at Mweka in Kasai, the last, slim chance of saving Lumumba from his enemies.11 Seen with the advantage of hindsight, the failure to protect Lumumba after his secret departure from Léopoldville joins the list of tragedies (including the Rwandan genocide and Srebrenica) that the UN failed to prevent by not taking action when action was still possible.

De Witte glowingly describes Lumumba as the hero of the “struggle between an international neo-colonial coalition on one side and the nationalist Congo on the other.” He believes that Lumumba belongs “in the pantheon of the universal defenders of the emancipation of the people.” He briefly mentions some of Lumumba’s mistakes and the “political weakness of Congolese nationalism, including the weakness of its central leader…,” and believes that Lumumba was deluded in thinking he would get help from Africa and Asia, from Moscow, and from the tiny Congolese elite that originally supported him. He does not say how much Lumumba’s personal conduct was responsible for this loss of support. African governments, for example, were shocked, and scared, by Lumumba’s appeal to the Soviet Union for military aid.

There is, unfortunately, a vast difference between noble aims, which Lumumba expressed eloquently, and the capacity and temperament to govern. The latter quality is especially important when a country is teetering on the brink of chaos. After independence and the worldwide publicity that engulfed him, Lumumba became increasingly autocratic, mercurial, and irresponsible. He frightened and alienated his government colleagues, and their growing fear of him and of his increasingly erratic conduct made them receptive, when the time came, to Belgian and other intrigues against him. When he launched the ANC into Kasai, 250,000 Luba became refugees in addition to the one thousand killed. De Witte sees Lumumba’s attack on the Luba of Kasai as a statesmanlike response to the prospect of secession, but it created serious doubts about his judgment, even his sanity, both within the Congo and outside it.

I cannot pretend that members of the UN mission, or anyone else that I know of for that matter, found that attempting to help Lumumba was a pleasant or rewarding experience. We had hoped to work with him in the desperately urgent task of restoring some degree of security and order and of getting his country going again. The UN was providing the only possible means and personnel for this purpose, but Lumumba preferred abusive rhetoric, ultimatums, threats, and demands for instant results. He cut off contact with Hammarskjöld and Bunche and appealed to the Soviet Union for military assistance. Saying that “blood will flow,” he threatened to violently expel the UN operation that was the one stable and constructive element in his country. Nonetheless Hammarskjöld, to the indignation of Belgium and the United States, protected him and made a prolonged attempt to bring about a reconciliation of Lumumba with Kasa Vubu and Mobutu—hardly the behavior of a neocolonialist.

At independence, it seemed possible that Lumumba would lead his people toward a bright future as a nation, a brief hopeful moment that Raoul Peck’s film poignantly captures. For many reasons, including the behavior of Lumumba himself, this promise was not to be fulfilled. The subsequent decline of the Congo under Lumumba’s successors, still continuing after forty years, is an even greater tragedy than Lumumba’s terrible death.

In 1963 and 1964, with all secessions ended and the full parliament reconvened, it seemed just possible that the Congo might begin to move forward as an independent nation. Such frail hopes were dashed in 1965 by the return to power of Washington’s supposedly anti-Communist protégé, Joseph Mobutu—reborn as Mobutu Sese Seko Kuku Ngbendu Wa Za Banga. For thirty-two years, under the admiring gaze of Western governments, Mobutu systematically plundered the Congo’s economy, leaving no financial or economic base for a future leader to build on, and a huge foreign debt.12

Mobutu’s replacement, Laurent Kabila, was no improvement. Since 1998, a war in the eastern part of the country, involving half a dozen neighboring countries, has been responsible, according to the International Rescue Committee, for 2.5 million deaths from various causes.13 A wide variety of international efforts, and the accession, after his father’s assassination, of Kabila’s reportedly sensible and responsible young son, have yet to turn the tide of disaster. The Congolese people, who, for more than a hundred years, have known only oppression, strife, and penury, are still waiting.

This Issue

October 4, 2001

-

1

The Belgian command inscribed the slogan “Après l’Indépendance = Avant l’Indépendance” on blackboards in the barracks of the Force Publique.

↩ -

2

I should explain here my own connection with the Congo. I was Ralph Bunche’s chief assistant and in that capacity was in the Congo throughout the summer and early fall of 1960. We were in touch with Lumumba more or less on a daily basis during this time, until he broke off relations with Bunche. In the fall of 1961, after Hammarskjöld’s death on a mission to the Congo, I became the UN representative in Katanga, was kidnapped and severely beaten up by Moise Tshombe’s troops, and was in charge of the UN side during two weeks of fierce fighting after which Tshombe agreed to end the secession and reunite Katanga with the Congo.

↩ -

3

Bunche, who had drafted the chapters of the UN Charter on decolonization and trusteeship and was awarded the 1950 Nobel Peace Prize for negotiating the armistice agreements between Israel and its Arab neighbors, had a unique record as a promoter and expediter of decolonization and was the friend and mentor of many of the African independence leaders. Lumumba once asked me angrily why Hammarskjöld had sent “ce nègre Américain” to the Congo. I replied with some heat that Hammarskjöld had only sent the best man in the world to deal with such a situation. Lumumba did not revert to this subject.

↩ -

4

See Alleged Assassination Plots Involving Foreign Leaders, interim report of the Senate Select Committee known as the “Church Report” (Norton, 1976), p. 53.

↩ -

5

Alleged Assassination Plots, pp. 13–16.

↩ -

6

“…chasser brutalement l’ONU de notre République…. S’il est nécessaire de faire l’appel au diable pour sauver le pays, je le ferai sans hésitation, persuadé qu’avec l’appui total des Soviets, je sortirais malgré tout victorieux.”

↩ -

7

See Madeleine G. Kalb, The Congo Cables (Macmillan, 1982), pp. 134–139.

↩ -

8

For details, see the Church Report, and Madeleine Kalb, The Congo Cables, pp. 128–133.

↩ -

9

The “Congo Club” became the informal name for the constantly changing group of officials who came together, usually when the rest of the day’s business was finished, to discuss the Congo situation with the secretary-general. It comprised, at different times, European, African, Asian, Latin American, and American secretariat officials. The Soviets latched onto the name as evidence of yet another Western conspiracy.

↩ -

10

“If the cold war settles in the Congo,” Hammarskjöld cabled Bunche on July 23, “our whole effort is lost.”

↩ -

11

The only sure means of protecting Lumumba would have been to take him into protective custody before his pursuers caught up with him. Lumumba, who until his arrest had been conducting a fairly leisurely and successful political swing through the country, would certainly have violently resented this, and one can easily imagine what his supporters in the outside world would have said about it.

↩ -

12

Michela Wrong’s In the Footsteps of Mr. Kurtz: Living on the Brink of Disaster in Mobutu’s Congo (HarperCollins, 2001) not only describes Mobutu’s calamitous kleptocracy, but also gives a perceptive, down-to-earth, and affectionate description of the people of the Congo under Mobutu’s tyranny.

↩ -

13

“Not Since World War II,” The Washington Post, August 26, 2001, p. B6.

↩