Virtually every major technology has been exploited not only for peaceful purposes but also for hostile ones. Must this also happen with biotechnology, which is rapidly becoming a dominant technology of our age? This is a question that comes to mind when reading Germs: Biological Weapons and America’s Secret War, a clear and informative account of biological weapons here and abroad by the New York Times reporters Judith Miller, Steven Engelberg, and William Broad.

Germs begins by describing the deliberate contamination in 1984 of salad bars in the small town of The Dalles, Oregon, with Salmonella typhimurium, a common bacterium that attacks the stomach lining and causes cramps and diarrhea. The bacteria were spread by members of a religious cult, who were apparently testing a plan to gain control of local government by keeping other citizens from voting in a coming election. Although they caused no deaths, their criminal actions caused sickness in some 750 people and illustrated a community’s vulnerability to even a relatively minor biological attack. A year passed before federal and state investigators established that the outbreak was not natural, and they were able to do so only because the cult leader himself called for a government investigation. The leader’s personal secretary and the cult’s medical care supervisor were sentenced to the maximum prison penalty of twenty years; they served less than four years and then left the country. Federal law enacted in 1994 raised the maximum penalty for such nonlethal biocrimes to life.

Americans have now experienced a far more sinister form of biological attack: seventeen cases of inhalation and cutaneous anthrax with four people dead and the person or persons responsible still at large. Yet the scale of the recent anthrax attacks was minuscule in comparison with the scale of preparations for continent-wide biological warfare conducted by major countries—notably the United States before President Richard Nixon categorically renounced biological weapons in 1969, and the Soviet Union, which even expanded its program after it was made illegal by the Biological Weapons Convention in 1975.

The advent of industrial-scale microbiology and therefore of industrial-scale biological weaponry was made possible by the proof of the germ theory of disease and the development of methods for growing pure bacterial cultures in the nineteenth century. These are accomplishments for which Robert Koch and Louis Pasteur are celebrated and which underpin the studies of tuberculosis for which Koch was awarded the 1905 Nobel Prize in Medicine. It was Koch who in 1876 described with great clarity the life cycle of the bacterium Bacillus anthracis and completed the proof that it causes the disease that is known in German as Milzbrand (fiery spleen), in French as charbon (because of the blackened scab it makes on the skin), in Russian as Siberskaya yasva (Siberian ulcer), and in English as anthrax (from the Greek for coal).

Anthrax is primarily an affliction of grazing animals. When multiplying in an infected animal, the bacteria are rod-shaped. But anthrax bacteria from the dead or dying animal, upon exposure to oxygen, form within themselves a tough-shelled ovoid spore that can remain dormant and infectious in the environment for years. The disease took a heavy toll among herds in Europe, Asia, and Australia until the introduction of effective veterinary vaccines, first one developed by Pasteur and then a safer and more effective vaccine developed in the 1930s by Max Sterne, a South African veterinary microbiologist. Sporadic natural outbreaks continue to occur throughout the world and have caused animal deaths and nonfatal human cutaneous cases in Minnesota, the Dakotas, and Texas this year.

The disease in human beings takes three principal forms, depending on what part of the body the spores enter and therefore on how the body responds. Most common and most easily curable with penicillin and other antibiotics is the cutaneous form, observed among people who come into contact with contaminated hides, hair, or bonemeal or who butcher infected animals. The gastrointestinal form, contracted by eating contaminated meat, is not uncommon in some poor countries and has not been much studied. Highly fatal in some outbreaks, it is less so in others. The inhalational form, mainly associated with occupational exposure to contaminated hides or animal hair, is usually fatal unless treated with antibiotics before or immediately after symptoms develop. It is this form of anthrax that has attracted the attention of those who seek to make biological weapons and those concerned to defend against them. Anthrax spores can be dispersed by bombs, aircraft spray tanks, or missiles as an aerosol sufficiently fine to remain suspended in the air and, if inhaled, to reach the depths of the lungs. Such weapons may be capable of rivaling nuclear ones in their power to kill people over large areas.

Crude anthrax bombs were produced by Unit 731 of the Japanese Imperial Army, which attacked villages in Manchuria with anthrax, plague, and typhoid during the Sino-Japanese war in the 1930s and 1940s. Under its creator and leader, General Shiro Ishii, the unit conducted vivisection and other lethal experiments on humans. After the Japanese surrender, he and several of his associates were granted immunity from war crimes trials by American officials in exchange for data from the Japanese biological weapons program.

Advertisement

The US biological weapons program, as the authors of Germs write, began in 1942, first directed by George W. Merck, then president of the chemical and pharmaceutical company founded by his father. Research, development, and pilot-scale production of biological weapons were conducted at Camp (subsequently Fort) Detrick, in Maryland. By the end of the war it had some 250 buildings and employed approximately 3,500 people, engaged in both offensive and defensive work. Large-scale production of anthrax spores and of botulinal toxin was planned to take place in a plant at Vigo, Indiana, near Terre Haute, built in 1944. The plant was equipped with twelve 20,000-gallon fermentors for culturing bacteria and with production lines for filling bombs. Its production capacity was estimated to be 1,000,000 to 1,500,000 British-designed four-pound anthrax bombs per month, requiring some 320 to 480 tons of a concentrated liquid suspension of anthrax spores. As noted in Brian Balmer’s deeply researched examination of British biological-warfare policy-making,1 Winston Churchill, in placing an initial order with the US for 500,000 anthrax bombs in March 1944, wrote that it should be regarded only as a first installment. Although the Vigo plant was ready to begin weapons production by the summer of 1945, the war ended without its having done so.

In 1947, the Indiana plant was demilitarized and leased and subsequently sold to Charles Pfizer and Company for the production of animal feed and veterinary antibiotics. It was replaced by a more modern biological weapons production facility constructed at Pine Bluff Arsenal, in Arkansas, which began production late in 1954 and operated until 1969.

A sizable effort of the 1950s, discussed in Germs, was the development and testing of anthrax bombs for possible attack on Soviet cities. The weapons to be used were cluster bombs holding 536 biological bomblets, each containing a liquid suspension of anthrax spores and an explosive charge fused to detonate upon impact with the ground, thereby producing an infectious aerosol to be inhaled by persons downwind. In order to determine the area effectively covered by the aerosol from a single bomblet and therefore the number of bombs required, 173 releases of noninfectious aerosols were secretly conducted in Minneapolis, St. Louis, and Winnipeg—cities chosen to have the approximate range of conditions of urban and industrial development, climate, and topography that would be encountered in the major cities of the USSR.

A problem with this project, which had the code name St. Jo, was uncertainty about the average number of inhaled spores needed to give a high probability of killing. Experiments at Fort Detrick involving 1,236 monkeys indicated that the ID50, the dose that would infect half the monkeys inhaling it, was 4,100 spores. Other experiments, carried out under different conditions, gave monkey ID50 values ranging from 2,500 to 45,000 spores. The army estimated that the ID50 for people might be between 8,000 and 10,000 spores, with lower doses expected to cause a correspondingly lower percentage of infections. But even leaving aside the variable results with monkeys, one could not know for sure if data derived from experiments with monkeys were at all applicable to people.

Inability to establish reliable munitions requirements and the possibility of creating long-lasting contamination eventually led the US Air Force to abandon plans to use anthrax as a lethal biological agent. It was replaced by Francisella tularensis, the bacterium that causes tularemia, a disease that inflames the lymph nodes and causes lesions in many organs of the body and can be fatal. Inhalatory tularemia can be dependably cured by prompt administration of antibiotics, and this made it possible to measure its infectiousness in human volunteers—Seventh-Day Adventist conscientious objectors in the 1950s. Inhalation of approximately twenty-five bacteria was found to be sufficient to give a 50 percent chance of infection. Untreated, the death rate of inhalational tularemia was thought to be up to 60 percent, depending on the strain employed.

Other agents were introduced into the US biological arsenal, including the bacteria of brucellosis and Q-fever and the virus of Venezuelan equine encephalomyelitis—all three of them incapacitating but much less often lethal than anthrax or tularemia—as well as fungi for the destruction of wheat and rice crops. The US arsenal also contained improved biological bombs for high-altitude delivery by strategic bombers and spray tanks for dissemination of biological agents by low-flying aircraft. These developments culminated in a major series of field tests of biological weapons using various animals as targets and conducted at sea in the South Pacific in 1968.

Germs tells the little-known story of Pentagon plans to attack Cuba with biological weapons in the event of a US invasion of the island during the 1962 missile crisis. The plans called for using incapacitating agents that were considered to be of relatively low lethality, and were expected to kill about one percent of those made ill. The authors quote a former Fort Detrick scientific director as believing that the use of such agents would have saved American lives. Others at the Pentagon thought it could have had the opposite effect. According to their hypothesis, not described in Germs, the defenders, feeling too ill to retreat, would have stayed in their foxholes and fortifications, using up all their ammunition before being overrun. The American attackers would therefore have been exposed to more fire than if germs had not been used, with correspondingly more loss of life. Whatever the result might have been, the use of biological weapons, even if expected mainly to incapacitate rather than kill, could, by breaking the prevailing international norm against germ warfare, have exposed Americans to far greater dangers later on.

Advertisement

Soon after becoming president in 1969, Richard Nixon ordered a comprehensive review of US biological and chemical weapons programs and policies, the first full study of the biological warfare program in more than fifteen years. Each relevant department and agency was instructed to evaluate several matters: the threat of biological weapons to the US and ways of meeting it; the utility of the weapons to the US; and issues raised by the possible distinction between weapons intended to be lethal and those meant only to incapacitate.

Six months later, on November 25, 1969, with the full support of the Departments of Defense and State, the President issued National Security Decision Memorandum 35, declaring that the United States would renounce all methods of biological warfare and that US biological programs would be confined to research and development for defensive purposes. In doing so he said that “mankind already carries in its hands too many of the seeds of its own destruction.” Three months later, after further interagency review, he similarly renounced the use of toxins (poisonous substances from living organisms), whether produced biologically or by chemical synthesis.

The US biological and toxin weapons stockpiles were destroyed and the facilities for developing and producing them were ordered dismantled or converted to peaceful uses. US biological stocks at the time were not very extensive, amounting to some 10,000 gallons of liquid incapacitating agents (the pathogens of Q-fever and Vene-zuelan equine encephalomyelitis), half a ton of dried lethal agents (anthrax and tularemia), some eighty tons of anti-wheat and anti-rice fungi, and about 100,000 munitions filled with various agents and simulated agents. Pine Bluff maintained a large standby production capacity for bacterial and viral antipersonnel agents, and a factory in Colorado was capable of supplying anti-crop fungi; there had, therefore, been no need to maintain large stocks.

President Nixon also announced that, after nearly fifty years of US recalcitrance, he would seek Senate agreement to US ratification of the 1925 Geneva Protocol prohibiting the use in war of “asphyxiating, poisonous or other gases, and of all analogous liquids, materials or devices” and of “bacteriological means of warfare.” Following the example of several other states, however, the US reserved the right of retaliation in kind and maintained active stocks of chemical weapons until the total ban, even on possessing such weapons, imposed by the Chemical Weapons Convention of 1993 took effect. Finally, Nixon announced support for a treaty proposed by the United Kingdom prohibiting the development, production, and possession of biological weapons, leading to the Biological Weapons Convention (BWC) of 1972.

These initiatives went far beyond the mere cancellation of a program. The US had categorically renounced the option to have biological and toxin weapons, whether intended to be lethal or only incapacitating. What was the underlying logic? First, it had become evident from the results of the US and British biological weapons programs that biological weapons, although subject to substantial operational uncertainties, could kill people, livestock, and crops over large areas. Second, US officials realized that the American biological weapons program was pioneering and legitimizing a technology that, once brought into existence, could be duplicated by others with relative ease, enabling a large number of states to acquire the ability to threaten or carry out destruction on a scale that could otherwise be matched by only a few major powers. The US offensive program therefore risked creating additional threats to the nation with no compensating benefit and would undermine prospects for combating the proliferation of biological weapons. If the US offensive biological program had continued to the present day, legitimating the weapons and advancing the technology for making them, how much greater would the threat now be and how much less would be the prospect of containing or averting it?

While the United States renounced biological weapons and abided by the Biological Weapons Convention, the Soviet Union secretly continued and intensified its preparations to be able to employ biological weapons on a vast scale. An example described at length in Germs was the standby facility built in the early 1980s for the production of anthrax bombs at Stepnogorsk, in what is now the independent republic of Kazakhstan. Subsequently dismantled in cooperation with Kazakhstan under the US Defense Department’s Cooperative Threat Reduction Program, it was equipped with ten 20,000-liter fermentors, apparatus for large-scale drying and milling of the spores to a fine powder, machines for putting it into bombs, and underground facilities for storage of filled munitions.

The first director of the Stepnogorsk facility, Kanatjan Alibekov, defected to the US in 1992 at the age of forty-two and simplified his name to Ken Alibek. In his account of the Soviet biological weapons program,2 he describes the atmosphere of fear in which it flourished. Incorrectly believing that the US renunciation was a hoax and citing “the biggest American arms buildup our generation had seen,” he found it easy to believe that the West would seize upon their moment of weakness to destroy them. The Stepnogorsk facility conducted dozens of developmental and test runs with anthrax so as to be ready to start full production should Moscow declare a “special period” for doing so. Moscow never did, and Stepnogorsk never produced a stockpile of weapons. Still, the purpose of the facility was to start production on short notice if it was ordered to do so. Other facilities at other locations were also established to produce infectious agents for war, not only the pathogens of noncontagious diseases such as anthrax and tularemia but also highly contagious ones, plague and smallpox. Alibek writes in his book, which is discussed in Germs, that in the 1970s the Soviet military command ordered the creation of a smallpox stockpile of twenty tons.

Soviet field-testing of biological weapons was conducted on Vozrozhdeniye Island in the Aral Sea. In a 1998 interview published in The Moscow Times, General Valentin Yevstigneev, then the senior biological officer in the Russian defense ministry, is quoted as saying that activities at the test site in the 1970s and 1980s were “in direct violation of the anti-biological treaty.”

To this day, the Russian Federation has done little to convince other nations that the offensive core of the Soviet biological weapons program has been dismantled. Despite the opening to international scientific collaboration of several of the largest research and development centers of the old program, such as the bacteriological research establishment at Obolensk and the virus research center at Novosibirsk, the former Soviet research and production facilities at Ekaterinburg, Sergiyev Posad, and Kirov, now belonging to the Russian Ministry of Defense, remain entirely closed to foreigners. The discussions of the US and the UK with Russia during the 1990s achieved agreement on the principle of reciprocal visits to each other’s military biological facilities as a means of resolving ambiguities, but they eventually ended in failure.

Nor has the Russian military seriously addressed remaining questions about the outbreak of inhalational anthrax in 1979 that killed at least sixty-four people in the Siberian city of Sverdlovsk (now restored to its former name of Ekaterinburg), despite the indisputable evidence described by Jeanne Guillemin in her authoritative book Anthrax: The Investigation of a Deadly Outbreak3 that the spores emanated from the Sverdlovsk military biological facility. Resolving these and other questions and establishing conditions that will allow the two nations to cooperate on an equal footing in fostering global compliance with the Biological Weapons Convention will require that biological weapons be given high priority in the dialogue between the US and Russia. Making common cause against terrorism, including bioterrorism, may provide the needed motivation.

One of the troubling implications of the anthrax bioterrorism since September 11 is that, even if the person or persons responsible for it desist or are caught, it may attract imitators. On the other hand, very few other lethal agents are as widely accessible and as stable in the environment as anthrax spores, and better means of prevention and better therapy for inhalatory anthrax are on the way. But there are thirty different bacteria, viruses, and fungi on the NATO list of biological weapons threats and there are additional agents on other lists. With sufficient effort, many of these could probably be modified so as to evade existing vaccines and antibiotics. It therefore seems reasonable also to consider more widely inclusive protections, not only those specific to a particular agent. A neglected yet simple measure that could offer considerable protection against any major aerosol attack and would also contribute to the reduction of respiratory disease caused by air pollution is filtration of the air that enters and circulates within large buildings.4 The most generic measures of all, however, are those that help to prevent and deter biological warfare and bioterrorism in the first place. Important among them is the Biological Weapons Convention.

The BWC serves the essential function of setting an international norm to guide the actions of states who see it in their interest to comply with the treaty, to dissuade states that may be tempted to violate it, and to facilitate joint international action against those found to be in violation. The convention obliges its members

never in any circumstance to develop, produce, stockpile or otherwise acquire or retain:

(1) Microbial or other biological agents or toxins, whatever their origin or method of production, of types and in quantities that have no justification for prophylactic, protective or other peaceful purposes;

(2) Weapons, equipment or means of delivery designed to use such agents or toxins for hostile purposes or in armed conflict.

A reasonable question can be raised about which biodefense activities are compatible with the spirit and the letter of the Biological Weapons Convention, and what information about legitimate activities should be kept secret. In their book and in their subsequent reporting, the authors of Germs reveal the existence today of three secret US biodefense activities: the partial recreation of a Soviet biological bomblet; the construction of a simulated biological weapons facility; and an attempt to recreate a strain of anthrax against which the standard Russian vaccine was reported by Russian scientists to be ineffective in laboratory animals.

The defensive value of these activities, each sponsored by a different government agency, is difficult to assess without more detailed informa-tion. Nevertheless, general information about the location, nature, and rationale of legitimate biodefense work ought to be available to Congress and the public. When the same information comes to light only as a leak to the press, this increases the risk of fueling arguments for provocative or prohibited biological weapons activities by governments elsewhere. What appears to be lacking here is any high-level oversight group authorized to keep watch on the entire range of secret defensive projects and qualified to judge the legitimacy, utility, and risks of each.

With some 144 states parties, membership in the BWC is now almost universal. The most important holdouts are in the Middle East. Egypt signed the treaty but has not ratified it. Syria and Israel, both thought by the US to have offensive biological programs, have not even signed. Iraq, required to join the convention under the terms of the Gulf War cease-fire agreement, is thought to have resumed its BW program after UN monitors left in 1998.

The Chemical Weapons Convention, with headquarters in The Hague, requires declarations from its member states of past and current activities and has some two hundred full-time inspectors trained to conduct both routine and short-notice inspections. By contrast, the BWC has no standing organization, no legally binding requirement for declarations, and no provision for investigations. Seeking to remedy this situation, in 1994 the member states of the BWC mandated the development of a protocol to strengthen the convention, including measures for verification. Last summer, with negotiating positions seeming to converge, the chairman of the group, Ambassador Tibor Tóth of Hungary, produced a consolidated text intended to gain general acceptance.

At that point, the Bush administration withdrew, rejecting the entire approach on grounds that it would do little to increase US confidence in com-pliance by others and would threaten disclosure of US biodefense and pharmaceutical company secrets. The government seems not to have appreciated that the potential value of such a protocol is not so much to increase US confidence as to decrease the confidence of any government weighing the pros and cons of noncompliance that their activity could long be kept hidden from other nations and shielded from sanctions.

One must wonder if the administration adequately appreciated the disadvantages of its action. Having rejected the current protocol approach after participating in it for seven years, how will we regain sufficient political credibility to win meaningful support for any new proposals we may advance? Without a mutually agreed verification arrangement, how will we find an international forum to undertake action to clarify present and future ambiguities in Russia and elsewhere? Without an internationally supported proto-col, and short of peremptory acts of war, how will we deal with facilities believed to be engaged in prohibited activities? And without the provisions of a protocol, how can we persuade others of the fact that we ourselves are not developing biological weapons, a perception that would be directly contrary to the US interest in preventing proliferation? The existence of US criminal law against biological warfare activities, applicable to private acts but not to acts of state, is not a sufficient answer.

Even with an agreed international mechanism empowered to investigate suspected violations and resolve ambiguities, backed up by national means of gathering information, there is a need for a system of internationally approved sanctions to reinforce the norm and help deter violations. The prohibitions embodied in the Biological Weapons Convention and the Chemical Weapons Convention are directed primarily to the actions of states, not persons. Yet any production or use of biological weapons must be the result of decisions and actions of individuals, whether they are government officials, commercial suppliers, weapons experts, or terrorists. So why not make the production and use of biological and chemical weapons a crime under international law? Treaties defining international crimes are based on the concept that certain crimes are particularly dangerous or abhorrent to all and that all states therefore have the right and the responsibility to combat them.

Such international criminal law would oblige each state that is a party to the treaty: (1) to establish jurisdiction with respect to the specified crimes extending to all persons in its territory, regardless of the place where the offense is committed or the nationality of the offender; (2) to investigate, upon receiving information that a person alleged to have committed an offense may be present in its territory; and (3) to prosecute or extradite any such alleged offender if the state is satisfied that the facts so warrant. The same obligations are included in international conventions now in force for the suppression of aircraft hijacking and sabotage (1970 and 1971), crimes against internationally protected persons (1973), hostage-taking (1979), theft of nuclear materials (1980), torture (1984), and crimes against maritime navigation (1988). It was on the basis of the Torture Convention that Britain asserted jurisdiction in the case of Spain’s request for extradition of former Chilean president Augusto Pinochet.

If such a convention were adopted and widely adhered to, this would create a new system of constraint against biological and chemical weapons. It would do so by applying international criminal law to hold individual offenders responsible and punishable should they be found in the territory of any state that supports the convention. Such people would be regarded as hostes humani generis, enemies of all humanity. The norm against biological and chemical weapons would be strengthened, deterrence of potential offenders would be enhanced, and international cooperation in suppressing the prohibited activities would be facilitated.

What about the question we began with? Will biotechnology, like earlier technologies, come to be extensively exploited for hostile purposes? That such an outcome is inevitable is assumed in “The Coming Explosion of Silent Weapons” by Commander Steven Rose,5 an arresting article that won awards from the US Joint Chiefs of Staff and the Naval War College:

The outlook for biological weapons is grimly interesting. Weaponeers have only just begun to explore the potential of the biotechnological revolution. It is sobering to realize that far more development lies ahead than behind.

If this prediction is correct, biotechnology could profoundly alter not only the nature of weaponry but also the environment within which it is employed. As our ability to modify life processes continues its rapid advance, we will not only be able to devise additional ways to destroy life but will also become able to manipulate it—including the fundamental biological processes of cognition, development, reproduction, and inheritance. In these possibilities could lie unprecedented opportunities for violence, coercion, repression, or subjugation. Thinking about the distant future has not heretofore been necessary in the history of our species. Averting or at least containing the hostile use of biotechnology may be an exception.

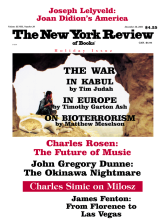

This Issue

December 20, 2001

-

1

Britain and Biological Warfare (Palgrave, 2001).

↩ -

2

Ken Alibek, with Stephen Handelman, Biohazard (Random House, 1999).

↩ -

3

University of California Press, 1999.

↩ -

4

See the comments on such filters by Richard Garwin in his article “The Many Threats of Terror,” The New York Review, November 1, 2001, and his reply to a letter from Stanley Crouch in the November 29 issue.

↩ -

5

Naval War College Review, Summer 1989.

↩