The two admirable shows currently at the National Gallery in Washington present works of art which, highly regarded though they might be today, were once held in even greater esteem. The landscapes of Aelbert Cuyp were admired and collected in the centuries after his death, until Holland was denuded of them. Treasured in English country houses, exhibited in London, they spoke directly and forcibly to painters of the nineteenth century, such as Constable and Turner. They were among the supreme representatives of their genre.

The portraits of women that have sur- vived from the Italian Renaissance were so eagerly sought after in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries that, as David Alan Brown tells us in the saner part of his catalog, whereas early Italian paintings in general remain scattered around the world, “almost all the female profiles found their way north of the Alps”—that is, into German, English, and subsequently American collec- tions. They were so highly prized, these profile portraits of women, that many fakes were produced in order to meet demand. Where a genuine portrait existed it was often attributed to a prestigious artist, and attached to the name of an equally prestigious sitter. By the time the great American collectors were fighting over the examples that remained (not all that many do remain), the prices had become very high indeed. Arabella Huntington paid $579,334.43 in 1913 for a pair of portraits attributed to Domenico Ghirlandaio.

Much later, in 1967, when the National Gallery acquired its portrait by Leonardo da Vinci of Ginevra de’ Benci (a portrait in the frontal mode, with something of the northern look of a Petrus Christus), it paid the highest price yet paid for a painting. It is around this work that the exhibition is organized, offering a small number of works of the very highest quality for intelligently chosen comparison. How the organizers persuaded both the Bargello and the Frick to lend their Verrocchio busts would be interesting to know. At a time when, in the wake of September 11, people are wondering whether such loan exhibitions can possibly continue, one felt a singular privilege in being able to view such a show.

What caught the imagination particu- larly, in the latter part of the nineteenth century and the first part of the twentieth, was the way Italian paintings celebrated women as individuals. Writing in 1860, Jacob Burckhardt—this is how Brown tells the story—“generalized from a few exceptional figures like Isabella d’Este or Vittoria Colonna” to exalt the women of the Renaissance. Burckhardt believed that in this period “women stood on a footing of perfect equality with men” and that “the educated woman, no less than the man, strove naturally after a characteristic and complete individuality.” In fact Burckhardt makes it clear that he is talking about high society, as a little fuller quotation from his text would have made clear: “To understand the higher forms of social intercourse at this period, we must keep before our minds that fact that women stood on a footing of perfect equality with men.” And:

In Italy, throughout the whole of the fifteenth century, the wives of the rulers, and still more those of the Condottieri, have nearly all a distinct, recognizable personality, and take their share of notoriety and glory. To these came gradually to be added a crowd of famous women of the most varied kind; among them those whose distinction consisted in the fact that their beauty, disposition, education, virtue, and piety, combined to render them harmonious human beings. There was no question of “woman’s rights” or female emancipation, simply because the thing itself was a matter of course. The educated woman, no less than the man, strove naturally after a characteristic and complete individuality. The same intellectual and emotional development which perfected the man, was demanded for the perfection of the woman.1

For the perfection of the educated woman, Burckhardt is saying.

It is a profoundly exciting passage—this evocation of a world in which the emancipation of woman was “a matter of course”—and if it reads excitingly today, how much more exciting must it have been to its original readers, to those men and women who made the pilgrimage to Florence with Burckhardt in their luggage. Brown tells us that Burckhardt’s view was popularized by “an outpouring of biographies and histories with such titles as The Women of the Renaissance (1905), Women of Florence (1907), and The Women of the Medici (1927).” He tells us how Dante Gabriel Rossetti managed to buy Botticelli’s Woman at a Window in 1867 (now in the Victoria and Albert Museum), and how American painters such as Thomas Wilmer Dewing painted their own profile portraits of women (in the example reproduced on page 14 of the catalog, the sitter is shown with a lute, an indication of rare artistic accomplishment).

Advertisement

What he does not go into, but would seem a promising area of inquiry, is the response to these portraits and biographies of women specifically among the women of the post-Burckhardt period. No doubt it has all been well charted somewhere, but it would have had a place here. After all, when Isabella Stewart Gardner acquired Piero Pollaiuolo’s Woman in Green and Crimson in 1907, for Fenway Court, her palazzo in Boston, she would have had the satisfaction of knowing not only that she had secured an object of some rarity. She would, had she consulted Burckhardt, have known one reason why such portraits were rare:

On the last day of the Carnival in the year 1497, and on the same day the year after, the great auto-da-fé took place in the Piazza della Signoria. In the centre of it rose a high pyramid of several tiers, like the rogus on which the Roman emperors were commonly burned. On the lowest tier were arranged false beards, masks, and carnival disguises; above came volumes of the Latin and Italian poets, among others Boccaccio, the Morgante of Pulci, and Petrarch, partly in the form of valuable printed parchments and illuminated manuscripts; then women’s ornaments and toilet articles, scents, mirrors, veils and false hair; higher up, lutes, harps, chessboards, playing-cards; and finally, on the two uppermost tiers, paintings only, especially of female beauties, partly fancy-pictures, bearing the classical names of Lucretia, Cleopatra, or Faustina, partly portraits of the beautiful Bencina, Lena Morella, Bina and Maria de’ Lenzi.2

In other words, it was such portraits as are gathered in the Washington show that formed the top two layers of the bonfires of the vanities. Indeed “the beautiful Bencina” mentioned as having had her portrait burned was probably a relative and namesake of the Ginevra de’ Benci painted by Leonardo.3 Not everyone in old Boston society thought those bonfires such a bad thing. Charles Eliot Norton (first professor of art history at Harvard) believed that the rot set in, in Florentine society, when they burned Savonarola.

Renaissance Italy was famous for its cult of women. As Margaret Fuller put it in 1845:

In Italy, the great poets wove into their lives an ideal love which answered to the highest wants. It included those of the intellect and the affections, for it was a love of spirit for spirit. It was not ascetic, or superhuman, but, interpreting all things, gave their proper beauty to details of the common life, the common day; the poet spoke of his love, not as a flower to place in his bosom, or hold carelessly in his hand, but as a light towards which he must find wings to fly, or “a stair to heaven.” He delighted to speak of her, not only as the bride of his heart, but the mother of his soul; for he saw that, in cases where the right direction had been taken, the greater delicacy of her frame, and stillness of her life, left her more open to spiritual influx than man is. So he did not look upon her as betwixt him and earth, to serve his temporal needs, but, rather, betwixt him and heaven, to purify his affections and lead him to wisdom through love. He sought, in her, not so much the Eve, as the Madonna.4

This is an early feminist reading of Dante and Petrarch.

Feminism has its history, just as art has, and it is sloppy of Brown to assert that “it was not until the advent of feminism and its application to art historical studies in the 1970s that a radically new approach to the female portraits arose.” It is made explicit by Burckhardt that his thinking about the equality of the sexes in the Renaissance takes place in a context of debate over female emancipation in his day. Likewise, when Brown says that “viewed from a feminist perspective, the portraits lost much of the allure they once had for earlier generations of art lovers and collectors,” he inadvertently makes a distinction between feminists, and art lovers and collectors. And then he writes:

The ideal celebrated by Burckhardt masked the reality of the vast majority of women’s separate but unequal status. It would not be too much to say that the feminists rediscovered the Renaissance woman, and their revisionist view was soon applied to representations of women in the visual arts. The fact that the Florentine portraits depicted ordinary and now mostly forgotten women made them ideally suited to the task.

Made whom suited to what task? And who says it is a fact that these sitters were ordinary women? The fact that their names have been mostly lost does not, of itself, make them “ordinary.” When we have a Renaissance portrait of an unknown woman in front of us, what we have is an image of a woman whose identity we do not know. It does not follow that she is a nobody, and indeed to call her a nobody is to make as much of a mistake as to call her Simonetta Vespucci or Isabella d’Este (plucking famous names from the air in the optimistic manner of the old art dealers).

Advertisement

The irony is that Brown knows this better than anyone. In his book on the early Leonardo, Leonardo da Vinci: Origins of a Genius, he shows in detail how it took more than a century after the first attribution of the Ginevra portrait to Leonardo for the identity of its sitter to be firmly and finally established. First there had to be agreement about what early Leonardo paintings might look like, but there was no such agreement. The consensus that finally emerged was resisted by eminent figures such as Berenson until the 1930s. And the identification of Ginevra de’ Benci was only finally confirmed, in a brilliant article by the English art historian Jennifer Fletcher, in 1989.5 Even now, there is disagreement about who commissioned the portrait, at what date, and for what purpose. Much hangs on the answers to these questions, all of it relevant to our idea of the sitter’s life.

Forgotten, but never ordinary, Ginevra de’ Benci came from a very rich Florentine family, married young as most girls did, but died a childless widow. As a young married woman she attracted the attention, and they say Platonic love, of the Venetian ambassador to Florence, Bernardo Bembo (himself a married man). Bembo came to Florence and took part in a joust arranged by the Medici. The mutual, but chaste, devotion of this couple was celebrated in a series of sonnets by members of the Medici circle, including some by Lorenzo de’ Medici which make an allusion to Ginevra’s having met with public disapproval and having retired to the country property of her family, and of her being like a lost sheep. She wrote poetry, of which one line has survived: “chieggo merzede e sono alpestro tygre“—“I ask your forgiveness and am a mountain tiger.” It sounds like one in what might have been a list of paradoxes.

What Fletcher in her article revealed was that the motto painted on the reverse of the portrait—VIRTUTEM FORMA DECORAT, or “beauty is the ornament of virtue”—belonged to Bembo himself, along with the device of the crossed laurel and palm which, together with a twig of juniper (alluding to the name Ginevra), are painted on the picture’s reverse, against a background of faux porphyry. It is one of the great strengths of the exhibition that we are shown both front and reverse of the portrait, together with comparable portraits with comparable reverses, including this same porphyry effect. Paintings of this kind might well have been hung on a wall, but they may also have been kept in the study as objects to be handled and admired by learned and appreciative visitors, of the kind who wrote those celebratory sonnets. The precious stone background would have suggested that the image was destined to last for ages to come. Bembo’s motto would have been a chivalrous tribute to his “love.”

Nobody seems able to explain—but it is a mystery that will occur to any reader of the catalog—how a young girl in the Florence of the day could pass from being a sequestered virgin scarcely allowed to set foot outside the house (which we are told was the standard condition of young girls) to being a married woman able to attract the attention and love of a visiting ambassador, and to have it known that the chaste affection was mutual. Brown compounds the mystery by suggesting that the portrait was made at the time of Ginevra’s marriage, but that Bembo later had the reverse painted (also by Leonardo). Quite how one broached the question to the husband or the family of a young married woman (“I am chastely in love with your wife—chastely, mind!—and wish to have my motto painted on the reverse of her portrait”) is a taxing question. If, alternatively, both the portrait and its reverse were commissioned by Bembo, we would still want to know what it meant for a man to commission a portrait of a young married woman not his wife.

At its most extreme, in the dreadful catalog essays written for this show, we get a view of women as no more than ciphers. The costume historians Roberta Orsi Landini and Mary Westerman Bulgarella tell us that

The wedding was the only moment in a woman’s life when she acquired social visibility as public personification of the ties between two families. She was only a medium, and in her profile portrait seems to be no more than a support for the signs of her husband’s power and wealth.

And Dale Kent is similarly dismissive: “In women even beauty is but the adornment of personal virtue; honor is a public virtue that pertains only to men.” (But on the same page Kent also tells us, equally falsely, that Dante, Petrarch, and Boccaccio were “the creators of the Tuscan language.” She really does not seem to care what she says, when the whim takes her.) If we followed this line on honor, which the author elsewhere in her piece contradicts, we would end up incapable of understanding either Italian literature or that body of work in the visual arts—painted portraits and medals—devoted to the honoring of women.

With very few exceptions, medals have always honored the persons depicted on them (the exceptions are immediately identifiable as satirical or, as in the case of the Pazzi conspiracy medal mysteriously included here as cat. no. 12, propagandistic). Pisanello’s medal for Cecilia Gonzaga honors her as a virgin and a daughter. The catalog entry describes precisely the kind of woman Burckhardt was thinking of:

Born in 1426, Cecilia, youngest daughter of Marquis Gianfrancesco Gonzaga of Mantua and Paola Malatesta, was educated in the classics alongside her brothers in Vittorino da Feltre’s famed Scuola Zoiosa. Something of a prodigy, she was noted for her academic achievement by all her contemporaries, including Ambrogio Traversari who commented on her proficiency in Greek. Despite her intellectual abilities, her father intended for her to marry the son and heir of the count of Urbino, Oddantonio da Montefeltro. Cecilia however, challenged paternal authority and sought to devote herself to the religious life. Eventually Gianfrancesco relented and in his will granted her permission to become a nun.

When the medal was struck, she was twenty-one and had been a nun for two years. Of all artifacts the most mobile, a medal was most likely to promulgate the fame of its subject—and that was the purpose of medals in general. The painted profile portrait aims to do in paint what the medal does in bronze. It does not imitate the medal (for these profile portraits are not circular) but it uses the same visual rhetoric. Like the medal, it is classical in its inspiration. Pisanello is credited with the revival of medals; he also painted a profile portrait of Ginevra d’Este. Joanna Woods-Marsden, who wrote a very interesting book on Pisanello,6 makes a distinction in her essay here between the meaning of the profile portrait in Ferrara and Rimini and the meaning in Florence: “The profile pose favored by the caesars for their coinage carried dynastic and political significance for the condottieri-princes that would have been unimaginable to a Florentine citizen, no matter how rich and influential.” But the Medici were the biggest medal collectors conceivable, and the distinction between the culture of the three cities in this regard seems untenable. The Florentines believed their city to be of Roman foundation, and to have been refounded by Charlemagne. They even believed their baptistery to be a Roman building. They were keen on things Roman.

The profile portraits give a suggestion of patrician virtue. What virtue itself might have been in a woman is defined very narrowly by Woods- Marsden: the female role was strictly procreative, so obedience, modesty and silence before marriage, fidelity after, and grave demeanor and self-restraint seem to sum the whole thing up. Identity, for the Renaissance female, Woods-Marsden says, “resided in the male, father or husband, who was responsible for her conduct and demeanor….” One gets the impression from this sort of writing that there are women out there who are absolutely determined to block our view of, or otherwise distract us from, any evidence of women’s accomplishments in the Renaissance.

And then there are, mysteriously enough, other women, who make the wonderful discoveries that bring the subjects of these once unidentified portraits vividly to life as individuals rather than as the constructs of some crude anthropology. I am thinking of scholars such as Jennifer Fletcher, mentioned above, and Carol Plazzotta, who in an article called “Bronzino’s Laura”7 recently illuminated the identity of Laura Battiferri, the sitter in a portrait by Bronzino in Florence.

Dated 1555, the portrait falls a little outside the period (1440–1540) of the Washington exhibition, although Bronzino’s work is there included. Battiferri was the natural daughter of an Urbino cleric, who became renowned for her learning and piety, and for her poetry. Widowed once, she married the sculptor Bartolommeo Ammanati, and formed part of a circle of Florentine poets and artists, with whom she corresponded. She published her own poems, and, in the manner of the day, poems written to her by admirers, who included Bronzino and Cellini. Because Bronzino’s portrait depicts her with a volume of poems open at two Petrarch sonnets, it was thought for a long time to show Petrarch’s Laura.

In fact it is of a woman who combined the virtue of Petrarch’s love with a profile reminiscent of Dante—for it is a profile portrait, reviving a mode by then long out of fashion. The praise, the “validation” Battiferri received, may be couched in male terms, but it has nothing to do either with the father who sired her in sin or, in what I have read, with her sculptor husband. It is her own. Burckhardt could not have known her identity, though he may well have known her portrait. We however can recognize her as one of his “crowd of famous women of the most varied kind” who “strove naturally after a characteristic and complete individuality.”8

The paintings of Aelbert Cuyp share with the female portraits of the Quattrocento a history of ambitious catalog descriptions: “Departure for the Hunt of the Prince of Orange; a clear and sunny Landscape, with the Prince of Orange mounted on a Grey Horse giving directions to a Garde de Chasse” turns out to be a study of a study of members of a newly emergent class, whose name had been bought only a generation back and who had only recently acquired the aristocratic right to hunt. A ruined castle in the background is a fiction, and the costumes the young men are wearing come from the artist’s stock of fancy dress. The painting, which belongs to the Metropolitan Museum in New York, is a glossy presentation of social aspirations.

One of these aspirations, the desire for a country retreat wherein to pursue the charms of gardening and horticulture, hunting, riding, friendship, and the family virtues, is connected in the catalog with a tradition of country house poetry, dating in Holland from 1613, and has its counterpart in English poetry at the same time, in such works as Ben Jonson’s “To Penshurst” (written before 1612) and Andrew Marvell’s later “Upon Appleton House” (circa 1650). The taste is international and can be traced back to Virgil and Horace. And there are elements in the art associated with it which are international too. For instance, the ruined castle that Cuyp invents to give some kind of historical perspective to the country estate he is depicting has its counterpart in the ruined nunnery upon which Marvell expends so many lines, out of which Appleton House grew.

You can see why these paintings appealed to an English sensibility. They are by no means Holland-bound. A Landscape with Horse Trainers, now in the Toledo Museum of Art, looks Italian but is somehow constructed out of elements taken from Utrecht (a Romanesque church) and a trip to the Rhine. The training of a horse to perform a tricky “levade” (rising on its hind legs while keeping its front leg tucked in) takes place among classical ruins and statuary, all in that evening light for which Cuyp is celebrated.

It is this light which makes the last room of this exhibition so stunning, where we see the Queen of England’s Evening Landscape and Cuyp’s largest work, the London National Gallery’s River Landscape with Horsemen and Peasants. Both paintings could have been painted from the same palette (if you can imagine a palette large enough to hold so much paint): that is to say, they give the same glow of gold and brown, and the same bravura effects of low light hitting various kinds of branches and reeds enliven the foreground.

The catalog tells us that, whereas we might expect the rich patrons who would have owned the National Gallery’s painting to identify with the figure on horseback (who faces away from us), there is a tradition in Dutch pastoral poetry of the period of celebrating the “wise herder.” The encounter may be between the ambitious courtier, whose life is open to the dangers of corruption, and embodiment of the simple virtues of the country life.

2.

The opinion expressed by Degas in old age, that a painting in a museum should be like an altarpiece, that it should not be moved around, is the diametrical opposite of that of the officials of the Guggenheim Museum, who have taken a look at some of the great permanent collections of the world and thought: Why should they not go for a ride? Why should masterpieces from the Hermitage or the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna not take a sabbatical in Las Vegas?

Of course the Guggenheim director Thomas Krens and his associates were not the first to come up with this idea or this location, but the success of Steve Wynn’s Bellagio Hotel in drawing publicity and paying visitors to its collection of Picassos convinced other entrepreneurs that here was an idea whose time had come, and the Venetian Hotel has opened a fairly small art gallery, charging $15 for admission, the same price charged by the new Guggenheim Museum itself, which has been built next to the Venetian. Actually the publicity for the Bellagio seemed to me larger than the achievement, last Christmas, when I dropped in on the Bellagio’s art gallery (currently closed) and saw its small exhibition. Most memorable was the system of lighting, which contrived to illuminate each painting and its frame but none of the surrounding wall, with the consequence that the paintings jumped out at you, gleaming and surprised, as from a bath of varnish. I disliked this exhibition very much.

The Bellagio is the most discreetly tony of the Las Vegas hotels, which means that the slot machines of its casino are for the most part muted, and you do not pass through the wall of sound with which you are greeted in the other lobbies and casinos. The Venetian, on the other hand, is just as hectic as the rest of them. And the new Guggenheim Museum opens directly onto one of these pinging hellholes, without any attempt at an intervening decompression chamber. But it is on a completely different scale from anything the Bellagio attempted, and since, for its first exhibition, it is showing motorcycles, reverent hush and awe are hardly in place. Anyway, there is awe, and plenty of it, in front of these machines. After spending some weeks “hurting” after September 11, the town was now hosting an automobile marketing convention, and although the museum has announced that attendance has fallen “short of expectations” there seemed to be plenty of visitors. They were down on their knees in front of the exhibits, in seraphic bliss, discussing points of design.

The show was a success. The space is very large indeed, handsome and industrial, designed by Rem Koolhaas, with, as it were, Richard Serra in mind. Anything vast would suit it hugely, and, since the space can be divided into an upstairs and downstairs, anything semi-vast as well. All that is required—and it has been laid on supremely well for the first show—is a phenomenally wholehearted attitude to exhibition design. For the motorcycles they brought in Frank Gehry, who created gleamingly reflective curtain-walls out of large fish-scales of stainless steel, with other mesh curtains for a matte contrast. Clearly this had all been very expensive, and the expense, as is often the case with exhibitions, was part of the experience. One would hate to have to run this Guggenheim with a less royal budget.

As it is, the museum has more than a hundred staff in Las Vegas, running its two spaces. The more conventional gallery in the Venetian, again by Koolhaas, houses masterpieces from the Hermitage and Guggenheim collections. The entrance gives off the garishly frescoed galleria connecting the lobby of the hotel to the casino—an unpleasant place to be. And it is odd to go from this ground-floor Hermitage to the reconstructions of the Grand Canal and St. Mark’s Square above, on the first floor. I was told that for their next show the organizers of this smaller space were thinking of the title “From Caravaggio to Jeff Koons.” I was also told that once the relationship with the Kunsthistorisches comes into play, they were hoping—although they had not yet secured the permission—to bring the famous Bruegels from Vienna.

There is no point in my pretending to like this prospect. Of the Vegas hotels I can bear Caesar’s Palace best, but would hate to see it offering classical works of art. Their sobriety would undermine the fantasy of imperial excess. One can see that, since Las Vegas does not stand still, something further in this direction will be projected (perhaps already has been), as long as the belief persists that works of art can travel profitably in such a way.

There is no doubt that the Kunsthistorisches and the Hermitage stand to benefit financially from exhibitions like these. The Bellagio under Steve Wynn proved that the calculation was right that, out of the 30 million visitors to Las Vegas per year, a small proportion might be prepared to look at some works of art, and that even a small percentage would bring in a large revenue. Whether this is something the Kunsthistorisches actually needs, or should come to rely on, is another matter.

In New York in early November, the Guggenheim was still installing the vast altarpiece, “considered a national treasure,” which is so tall it occupies the entire center space of the museum, where it “helps to contextualize” the Baroque religious objects on view in “Brazil: Body and Soul.” Striking publicity for Brazil, but less good for the inquirer into the Brazilian baroque, who finds an assortment of a polychrome sculpture of indifferent quality, somewhat overexposed by the elaborate display.

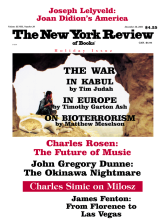

This Issue

December 20, 2001

-

1

Jacob Burckhardt, “Equality of Men and Women,” in The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy (London: Phaidon, 1945) pp. 254–255.

↩ -

2

Burckhardt, The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy, p. 314.

↩ -

3

See David Alan Brown, Leonardo da Vinci: Origins of a Genius (Yale University Press, 1998), p. 201, note 15.

↩ -

4

Margaret Fuller, Woman in the Nineteenth Century and Other Writings (Oxford University Press, 1994), p. 42.

↩ -

5

Jennifer Fletcher, “Bernardo Bembo and Leonardo’s Portrait of Ginevra de’ Benci,” Burlington Magazine, December 1989, pp. 811–816.

↩ -

6

Joanna Woods-Marsden, The Gonzaga of Mantua and Pisanello’s Arthurian Frescoes (Princeton University Press, 1988).

↩ -

7

Burlington Magazine, April 1998.

↩ -

8

For an interesting account of the relationship of Bronzino to Battiferri, and their poetry, see Deborah Parker, Bronzino: Renaissance Painter as Poet (Cambridge University Press, 2000).

↩