Many rich countries have tried hiring foreigners to do their dirty work. Few have been happy with the results. Hiring immigrants for unskilled jobs seems a good deal for the employer. Immigrants will usually accept lower wages than natives, and at least in the United States most employers report that immigrants are more diligent, more reliable, and less prickly than the Americans who apply for such jobs. But hiring unskilled immigrants does not make unskilled Americans disappear; it just depresses their wages. In the long run, moreover, hiring unskilled immigrants has another significant cost. Most immigrants eventually have children, and while many of these children thrive in their new homeland, many do not.

I argued in an earlier article that assimilating the children of Southern and Eastern European immigrants was relatively easy in the first half of the twentieth century because the wage gap between their parents and American-born workers was fairly modest. I also noted that the wage gap between immigrants and American-born workers in 1998 was three times what it had been in 1910.1 This article takes up the question of how that change, along with many others, is likely to affect recent immigrants’ children. I then discuss why some might want to limit the total number of immigrants, regardless of their characteristics, and why Congress keeps letting the number rise.

1.

Most Americans assume that once immigrants arrive in America our goal should be to make them more like us. We usually refer to this process as Americanization or assimilation. Legacies, by Alejandro Portes and Rubén Rumbaut, tracks the Americanization of second-generation immigrants in the San Diego and Miami areas. The book’s most valuable contribution is to show why so many immigrants are ambivalent about Americanization and why we should share this ambivalence. The reason is obvious once you think about it. Whether Americanization is good or bad for immigrants depends on which Americans the immigrants come to resemble. Immigrants tend to be poor. If their children come to resemble the children of poor Americans, they are headed for trouble. Portes and Rumbaut call this “downward assimilation.”

Many children who assimilate downward tend to stop doing their schoolwork fairly early, often because they find it hard, particularly if they have difficulties with English. By the time they reach high school some have stopped doing most of the other things that grownups want them to do. Instead they may join gangs, use a lot of drugs and alcohol, have children out of wedlock, get arrested, and spend time in jail. They then reach adulthood with no social or technical skills that would qualify them for a good job. Indeed, their attitudes often make employers reluctant to hire them even for menial jobs like the ones their parents hold.

Downward assimilation is far from universal, even among children of extremely poor immigrants. Most second-generation immigrants get somewhat more schooling and earn somewhat higher wages than their parents.2 But there are millions of exceptions, so most immigrants worry a lot about the risks to which their children are exposed. Many blame America’s urban schools for not maintaining order, teaching respect, and instilling discipline. Some try to protect their children by moving to safer suburban districts, even when this means cramming six or seven people into three or four rented rooms. But while suburban schools are usually safer than inner-city schools, many immigrants still find them too permissive. Portes and Rumbaut report that some anxious Caribbean immigrants send their teenagers back to the islands for secondary school.

The Handbook of International Migration: The American Experience, edited by Charles Hirschman, Philip Kasinitz, and Josh DeWind, is the best available introduction to what we currently know about noneconomic aspects of migration to the United States. In one chapter Rubén Rumbaut surveys much of the evidence on downward assimilation. The most revealing comparisons involve immigrants’ teenage children. Some of these teenagers have spent their entire lives in the United States. Others have spent their early years in Asia, Latin America, or the West Indies before moving to America.

The longer these teenagers have spent in the United States, the more likely they are to behave in ways that most parents deplore. Those born in America have sex at an earlier age and are more likely to become teenage parents. They also drink more, use more drugs, and report more delinquent behavior than teenagers who have spent their childhoods in Latin America or Asia. Latino and Asian adults are also more likely to be in prison if they were born in the United States than if they were born in Latin America or Asia.3 All these differences suggest that living in America undermines parents’ ability to control their children’s behavior.

Growing up in America also seems to be bad for teenagers’ health. Asian and Latino teenagers born in the United States are more likely to be overweight than those who come here later, presumably because America’s diet includes more fats and sugars. In addition, adolescent Latinos and Asians are more likely to report having asthma if they were born in the United States rather than Latin America or Asia.

Advertisement

These differences help to explain another paradox. Despite the fact that second-generation adults usually have more education and income than their parents, second-generation mothers have more low-weight babies and higher infant mortality than first-generation mothers.4 One reason is that those born in America are more likely to smoke and drink while pregnant.5 Pregnant Latinas have unhealthier diets and take more drugs if they were raised in the United States than if they were raised in Latin America.6

All this is, I fear, the dark side of the same economic system that draws so many immigrants to America. America’s laissez-faire economy is unusually productive, but its laissez-faire culture produces an unusually high level of short-sighted, anti-social, and self-destructive behavior. American infants are more likely to die than infants in other rich countries.7 Accidents kill more children in America than in any other rich country.8 American ninth graders use more amphetamines and cocaine than ninth graders in other rich countries.9 American teenagers also have many more babies than teenagers in other rich countries.10 And young adults murder one another more often in America than in other rich countries.11 There are exceptions to this gloomy litany. American teenagers do not rank especially high on alcohol abuse or suicide, for example.12 Still, for the children of immigrants, being born in America brings more downside risks than being born in other rich countries.

Such statistics do not imply that immigrants’ children would have been better off if their parents had not come to America. We do not have infant mortality statistics for children whose parents are still waiting to get into America, but we know that Mexico’s infant mortality is four times America’s, while Mexican mothers who come to the United States have infant mortality rates below those of non-Hispanic whites. This contrast strongly suggests that coming to America reduces the risk that a baby will die. We also know that the murder rate is twice as high in Mexico as in the United States. We don’t know how many Mexicans are murdered in the United States, but a Mexican teenager’s chances of being murdered may well be lower here than there. My point is not that immigrants’ children would be better off in their countries of origin, but that while unskilled immigrants seem able to benefit from America’s economy without succumbing to the social ills that afflict other poor Americans, these immigrants’ children do not enjoy the same kind of immunity.

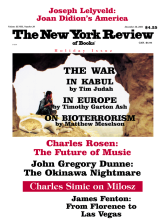

Table: Immigrants Granted Legal Residence in the United States

2.

Many native-born Americans equate assimilation with becoming fluent in English. If people talk like Americans they are Americans, no matter where they or their parents were born. David Lopez, a UCLA sociologist, surveys the evidence on linguistic assimilation in The Handbook of International Migration. The best data come from a 1989 Census survey that asked young adults whether they spoke English at home and if not, how well they spoke it. For simplicity, I will describe people as “fluent” in English if they either spoke it at home or said that they spoke it “very well.” By this standard, half the Asians who had come to America as adults were fluent English speakers in 1989, compared to a quarter of all Latinos and an eighth of the Mexicans. One reason Latinos know less English is that they have less education. Another reason is probably that some employers in cities like New York and Los Angeles hire only Spanish speakers for certain tasks. Those who work in such settings have little reason to improve their English.

Many Mexicans also see themselves as sojourners who will return home once they have made some money. The typical Mexican male earns about half what a non-Latino white earns, so if he compares himself to other Americans he is likely to feel like a failure. But if he compares himself to the Mexicans with whom he grew up, he is likely to feel quite successful. So he clings to his Mexican identity, sends money back to his parents, goes home for holidays with gifts that his relatives could not otherwise afford, tries to buy property in Mexico for his retirement, and retains his Mexican citizenship. Among Mexican immigrants legally admitted to the United States in 1982, only 22 percent had become American citizens by the end of 1997, compared to about 40 percent of those who came here from the Caribbean and well over half of those from Asia.13

Second-generation immigrants almost always know more English than their parents, but Latinos still lag behind Asians. Among young Mexican adults born in the United States, a fifth say they do not speak English very well, compared with only 5 percent of Asians.14 Unfortunately, we do not know exactly what people mean when they say they do not speak English “very well.” Even people who speak no other language may not feel they speak English “very well.” The available surveys suggest that a sizable number of second-generation Latinos may have trouble communicating in English, but they do not prove that this is the case. Figuring out how many Americans have trouble understanding and speaking English surely ought to be a high priority, but it does not seem to be.

Advertisement

Roughly 10 percent of the American population now speaks Spanish at home. These households are concentrated in and around a few cities, where Latinos are becoming a major political force. Strangers Among Us, by Roberto Suro of The Washington Post, provides a vivid description of the Mexican-American “borderlands” that have sprung up in Southern California and Texas. The United States has not had much experience with large, permanent linguistic ghettos of this kind. We have no way of knowing whether their growth will make mastery of English less common. The Anglo population has, however, grown increasingly alarmed by the prospect that Spanish could displace English in such areas. During the 1990s most American states voted to make English their official language. Such laws have little practical effect, but their popularity suggests that symbolic confrontations over language are likely to grow more common and more divisive if the Bush administration persuades Congress to admit even more Mexicans.

3.

When I tell friends that many immigrants’ children do badly in the United States, their first instinct is frequently to blame racism. Black Identities, by Mary Waters, provides a telling description of how old-fashioned racism can transform the children of black immigrants into an alienated and rebellious underclass. Waters interviewed just over two hundred West Indians living in New York City. Their parents had come from Guyana, Jamaica, Trinidad, or one of the smaller English-speaking islands. Most were fairly well educated and ambitious. Most were also very critical of American-born blacks, whom they saw as lazy, irresponsible, and inclined to blame whites for problems they had brought on themselves. These West Indians saw themselves as better workers than American-born blacks, and New York employers seemed to agree. As a result, almost all the West Indians found work. They also earned a little more than American blacks with the same amount of schooling.

But the longer West Indians had lived in New York, the more racism they had experienced. Some of these incidents involved fairly subtle slights, such as a teacher expressing surprise when a student handed in a good paper. But some of the incidents were extremely raw, such as being called a “fucking nigger” by an ill-tempered customer or watching the police beat a black man on the street. Such experiences made the West Indians more suspicious of whites and more inclined to see racism as a major obstacle to their own economic progress. They still believed in education, hard work, saving money, and other bourgeois virtues, but they were less optimistic about how far these virtues could take them. Waters does not discuss the economic consequences of this shift in attitudes, but if West Indians became more suspicious of their employers, their employers probably reciprocated.

The American-born children of the West Indian immigrants in Waters’s study responded to New York in two distinct ways. Some of them distanced themselves from American blacks and emphasized their West Indian roots. They knew that New Yorkers saw West Indians as less threatening and more competent than American blacks, so they made all kinds of efforts to call attention to their ancestry. When Waters asked them how they listed their race on forms, for example, some said that instead of checking “black” they wrote in “Jamaican,” “Caribbean,” or “other.”

But most American-born West Indians took a different view, identifying with American blacks and distancing themselves from American whites. According to Waters they often put down their schools for promoting white culture or disparaged academic success as “acting white.” They also stressed the pervasive influence of white racism and said that nobody like them had much chance of doing well in America. Their parents referred to this position as “being racial” and saw it as an excuse for their not working hard or acting responsibly. The children saw their parents as naive foreigners who did not understand America.

These young West Indians provide a particularly disturbing example of downward assimilation because their parents mostly had steady jobs at respectable wages. I suspect, however, that many children of middle-income American blacks follow a similar trajectory. Such children generally do worse in school than whites from similar backgrounds, and they also seem to get into more trouble as teenagers. Of course, adolescents of all races welcome excuses for not doing their schoolwork, like to see themselves as victims, and identify with excluded groups. But being black seems to make those tendencies harder to resist, at least in America, and it has more serious consequences for those who come to school with fewer academic skills.

As Waters emphasizes, young West Indians know that whites in general and the police in particular see them as a source of trouble, especially if they are male. But the West Indians who complained about such white stereotypes were not trying to look reassuring. They often wore flattops, baggy pants, and jewelry in order to look cool. At least to untrained adult eyes, their dress and demeanor must have made them look like gang members. Those who dress like gang members should not be surprised when they are treated like gang members, although they have a right to be angry too.

Although Black Identities provides overwhelming evidence that race continues to shape the attitudes and opportunities of young blacks in America, generalizing from the experiences of black West Indians to all “people of color” is almost certainly a mistake. The stereotypes that shape the relationships between white Americans and either Asians or Latinos have little in common with the stereotypes that shape relations between whites and blacks. White Americans are not surprised when an Asian student hands in a good paper or when a Mexican worker in California holds two arduous jobs.

Intermarriage rates suggest that the social distance between whites and blacks is also far greater than that between whites and either Asians or Latinos. Only 6 percent of married black men and 3 percent of married black women had a non-black spouse in 1998.15 Both figures have risen by half since 1980, but such marriages remain unusual. The picture among Asians and Latinos is completely different. The New Americans is a report on the demographic and economic effects of immigration, prepared under the auspices of the National Research Council by a panel of distinguished scholars. It indicates that while almost all Asian immigrants marry other Asians, a third of their children and over half their grandchildren marry non-Asians. The figures for Latinos are almost identical.

High levels of intermarriage will make it harder and harder to tell who is Asian and who is European. The physical implications of marriages between Latinos and non-Latino whites are not so clear. Roughly half of all Latinos living in the United States describe themselves as white. Most of the rest say they are neither white, black, Asian, or American Indian but “some other race.” If Latinos who marry non-Latino whites look as white as their spouses, most of their children will also look and act white, even if they decide to call themselves Latinos on their college applications. If most Latino–white marriages are of this kind, America’s Latino population will divide, with light-skinned Latinos joining America’s white majority while dark-skinned Latinos make up a separate “racial” group, whose members mostly marry one another.

Portes and Rumbaut suggest that an “oppositional” subculture like the one that Waters found among West Indians has also developed among some young Mexicans. If this subculture is associated with skin color, the chances of a division appearing among Mexicans will be even higher. If that happens, dark-skinned Latinos could end up in a position similar to African-Americans. Indeed, this has already happened to some extent among Dominicans and Puerto Ricans in New York.

Alternatively, dark-skinned Latinos may also begin marrying non-Latinos. Most Latino immigrants now come from Mexico and Central America. Those with darker complexions usually have more Indian ancestors than those who do not. Intermarriage between Europeans and Indians has been common for centuries, both north and south of the Mexican border. In 1990, for example, 71 percent of married American Indians said they had a white spouse.16 If dark-skinned Latinos follow this precedent, the physical differences between Latinos and non-Latinos will fade over time.

4.

In Heaven’s Door, George Borjas argues that immigration policy involves two fundamental choices: how many immigrants to admit, and which ones. Borjas provides a wealth of information about the consequences of admitting different kinds of immigrants, but he offers little guidance on how many to admit. The United States welcomed European immigrants during the nineteenth century because it wanted to fill the continent with Europeans who would not only expand the labor supply but help subdue the Indians and extend the nation’s borders. Today, however, most Americans live in or near cities and think their country is overcrowded. This shift in attitudes has been accompanied by a sharp drop in fertility. If we ignore immigrants and their children, Americans no longer have quite enough children to replace themselves. As a result, America’s future population depends largely on its immigration policy.

The New Americans estimates the total population of the United States in 2050 using five different assumptions about immigration. Its predictions range from a low of 307 million to a high of 463 million. But if immigration keeps growing by about three percent a year, as it has since 1965, total immigration will exceed the panel’s maximum estimate, and America’s total population in 2050 will be over half a billion—about twice the current figure.

In The Case Against Immigration, Roy Beck argues that doubling America’s population would be a big mistake. Apart from some business executives, I have never met anyone who favored doubling the population, so I assume Beck’s feelings are widely shared. Most Americans want to live near a densely populated area, because that is where the best jobs are mostly located. But few Americans want to live in a densely populated area. They keep moving out of central cities and high-density suburbs to more remote suburbs where they can get bigger houses and bigger yards for less money. Doubling the population of any given metropolitan area will mean that people have to drive further to get the same amount of living space. No legislator would publicly endorse a policy that increased commuting time or forced more people to live in apartments or on smaller lots. But the connection between immigration and population density hardly ever comes up when Americans discuss immigration policy.

No one knows how doubling America’s population would affect our physical environment. Western Europe, which is twice as densely populated as the eastern half of the United States, is not an ecological disaster area. Indeed, most Europeans prefer life there to life here. But Europeans subsidize mass transit, pay high gasoline taxes, curb urban sprawl, and subsidize farms that help preserve open space. Americans show little enthusiasm for such policies. Americans do care about rush hour traffic, which would presumably be a lot worse if the number of commuters doubled. America may also have trouble finding enough clean water for half a billion people, especially if politicians from arid states keep insisting that their farmers also have an inalienable right to huge quantities of subsidized water. Such problems are surely soluble, but solving them will have economic and political costs (including higher taxes) that seldom come up in discussions of immigration.

Doubling America’s population could also impose significant costs on the rest of the world. The United States currently accounts for almost 25 percent of the world’s carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions, making it the leading contributor to global warming. Americans produce twice as much CO2 per capita as the British, Germans, or Japanese.17 All else being equal, doubling America’s population will double our emissions. If we want to hold our emissions at their current level while doubling our population, we will have to cut per capita emissions in half—a huge challenge. If we actually want to reduce our emissions, the challenge is even greater. No other rich country is contemplating population growth of this kind. Most are worrying about population declines.

In principle America could reduce CO2 emissions by replacing sales taxes with carbon taxes, driving smaller cars, and requiring manufacturers to make other products more energy-efficient. But there is little political support for any of these policies. If the United States were forced to choose between such measures and slowing population growth by admitting fewer immigrants, most Americans would almost certainly prefer reducing immigration. Since the early 1980s well over half of all Americans have wanted to reduce the flow of immigrants. Fewer than 10 percent have favored increases in immigration. The rest say we should keep immigration as it is.18

In 1965, when Congress voted to eliminate national origin quotas, nobody seems to have expected that the number of immigrants would rise as a result. The President, the secretary of labor, and the secretary of state all promised that the new law would leave the total number of immigrants unchanged. So did the bill’s chief sponsor in the House, Emmanuel Celler. Senator Robert Kennedy, who was one of the bill’s sponsors, claimed that it would raise annual admissions by about five thousand for a few years, but that admissions would then return to their pre-1965 level.19 All these predictions proved false.

The dark line in the chart on page 95 shows that legal immigration began to climb almost as soon as the new law passed. By the mid-1980s immigration was averaging 600,000 a year—more than double the pre-1965 level. Including illegal immigrants would raise the totals by about a third but would probably not change the trend. Subtracting immigrants who return home would lower the totals by perhaps a fifth, leaving them quite close to those in the chart.20 The dashed curve in the chart shows the underlying trend in legal admissions if we ignore the 1986 amnesty.21 If this trend were to continue, either because of incremental changes in the number of legal admissions or because of new amnesties, the total population would, as I have suggested, exceed 500 million by 2050.

When I first made these calculations, I viewed them as statistical fantasies. Long before 2050, I thought, the electorate would revolt. Every European country that has experienced high levels of immigration has seen such a revolt. But Congress will not curtail the growth of immigration just because poll data show that the public favors such a change. Immigration will level off only if the political groups that drove it up over the past generation become weaker or if those who want immigration reduced become stronger. Once I posed the problem this way, my statistical projections no longer seemed so fanciful.

America’s baby boomers will start to retire in a few years. Once that happens, the number of college graduates leaving the labor force every year will be almost as large as the number joining it. If high-tech firms want to keep growing, they will need to find more technically skilled workers. The principal sources of such workers are likely to be countries with large populations, reasonably good universities, and relatively bad governments, because these countries will produce a lot of well-educated people who want to leave. At the moment, the biggest exporters of skilled workers are India, China, and Russia. No high-tech firm is likely to move to Russia. So those that want to grow will either have to move more of their operations to Asia or bring more Asians and Russians here. Faced with that choice, Congress will probably decide to admit more immigrants with advanced degrees. Indeed, it has already begun to move in this direction, although it currently describes these workers as “temporary.”

Those who want the United States to admit more unskilled workers are also likely to grow more influential. Immigrants who want to get their relatives into the United States are becoming more numerous, and more of them are beginning to vote. Second- and third-generation Latinos and Asians are less likely to have immediate relatives outside the US, but they are still likely to oppose legislation that appears “anti-Latino” or “anti-Asian.”

Meanwhile, organized opposition to immigration has grown weaker. The AFL-CIO concluded last year that it should try to organize immigrants rather than reduce their numbers. No other large-membership organization tries to limit the number of immigrants. In the absence of grass-roots organizations that threaten to retaliate at the polls against legislators who support immigration, Congress has little incentive to cut it. The “green cards” that allow people to reside permanently in the United States are worth a lot to recipients and their relatives. Since the 1970s Congress has learned to treat these permits like other forms of political pork. Legislators who work to expand the number of green cards win friends. Legislators who work to reduce the number make enemies. Unless that changes, immigration will keep expanding no matter what the polls show.

Congress has appointed two blue-ribbon commissions to review immigration policy over the past quarter century. The first was chaired by a liberal Catholic, Father Theodore Hesburgh. In 1981 it recommended reducing the number of legal immigrants and clamping down on illegal immigration. The political climate was then favorable to this view. Unemployment was at its highest level in forty years, and the Reagan administration was telling journalists that America had “lost control of its borders.” Five years later Congress passed IRCA, which was supposed to curtail illegal immigration. IRCA was billed as a compromise, which offered illegals already living in the United States an amnesty while discouraging new illegals from coming here by imposing stiff penalties on employers who hired them. To no one’s surprise, the new rules against hiring illegals proved unenforceable, so IRCA’s only enduring legacy was the amnesty.

Having dealt with illegal immigration, Congress turned its attention to legal immigration. Then as now, the main rhetorical rationale for legal immigration was “family reunification.” Spouses, parents, and dependent children of US citizens were admitted without any numerical limit. Spouses and children of noncitizens were also admissible but were subject to numerical quotas. There were also quotas for the grown children and siblings of citizens. This last provision mainly benefits naturalized citizens, allowing them to bring in their relatives, who can then bring in their relatives, ad infinitum. This process is known as chain migration. The law also provided for some admissions to do specified jobs, which the labor movement regarded as too generous and the business community regarded as too restrictive. A separate set of laws allowed the president to admit political refugees and asylum-seekers. This system is still in place today.

When Congress took up legal immigration in 1989, employers, human rights groups, ethnic and religious groups, and immigration lawyers were all pushing for more generous quotas. Nonetheless, the two senators who had over the years acquired the greatest influence on immigration policy, Edward Kennedy and Alan Simpson of Wyoming, introduced a relatively restrictive bill. Simpson wanted an overall limit on the number of immigrants admitted each year. He also wanted to reduce chain migration by cutting the quota for adult siblings of US citizens. Kennedy felt that the family reunification system had shortchanged the Irish, who no longer had close relatives in the United States. He therefore proposed a new quota for skilled workers under which applicants would get extra points if they were fluent in English. The Senate had approved these proposals in 1988, but the House had done nothing. This time, however, Latino and Asian lobbyists persuaded the Senate Judiciary Committee to kill both Kennedy’s plan for helping English-speaking applicants and Simpson’s plan for reducing chain migration. When the Kennedy-Simpson bill reached the Senate floor, a pro-immigration coalition led by Orrin Hatch (the Judiciary Committee’s senior Republican) and Dennis DeConcini (a Democrat) eliminated the overall numerical limit on immigration as well.

The chairman of the House subcommittee on immigration, Bruce Morrison of Connecticut, pursued a more successful political strategy. By expanding total annual admissions he was able to draft a proposal that offered each important House Democrat something he cared deeply about, and the House approved the bill. Peter Schuck, who teaches law at Yale, reports in Citizens, Strangers, and In-Betweens that when the conference committee met to resolve the differences between the House and Senate bills, Simpson listed his many objections to the House bill and asked each House participant to describe his “bottom-line” requirements. According to Schuck, Morrison insisted on provisions favorable to the Irish. Joe Moakley, the Massachusetts Democrat who chaired the House Rules Committee, demanded asylum for Salvadorans. Howard Berman, a California Democrat from a predominantly Latino district, wanted more generous treatment for Asian and Hispanic families. Charles Schumer, who represented part of Brooklyn at the time, said his top priority was a new “diversity” program that would initially help the Irish and eventually distribute about 50,000 green cards through a worldwide lottery. The conference report included al these provisions. In return, Simpson won approval for an experiment in which three states would issue secure drivers’ licenses that employers could use to distinguish legal residents of the United States from illegals.

When the conference report came back to the House, the Hispanic Caucus insisted that Simpson’s experiment be dropped. This was a risky move. Kennedy had promised to oppose any bill that Simpson opposed, so if Simpson withdrew his support the legislation was likely to die, frustrating the Hispanic Caucus’s efforts to raise annual admissions. But legal and illegal Hispanic immigrants make up a single community. Legals and illegals often live in the same household. In some cases they are married to each other. Protecting illegals who are already in the United States has therefore become as important to many Hispanic legislators as expanding the number of legal admissions. But for reasons that remain unclear to me, Simpson agreed to drop the ID experiment. The House then approved the revised bill, and President Bush, who had earlier theatened a veto, signed it into law.

The 1990 law set up another blue-ribbon commission, headed by a popular former Representative from Texas, Barbara Jordan. In 1994 and 1995 it issued a pair of reports urging Congress to reduce the number of illegal immigrants and make hiring illegals more difficult. Once again the political climate seemed favorable. Fifty-nine percent of California voters had just endorsed Governor Pete Wilson’s proposal to withhold all forms of public support from illegal immigrants, and those who wanted to admit more immigrants were running scared. Once again quotas for grown children and siblings of American citizens became a central issue. President Clinton initially supported the Jordan Commission’s recommendation that these quotas be cut, apparently because he thought this would help him carry California in 1996. But according to James Gimpel and James Edwards, the authors of The Congressional Politics of Immigration Reform, Clinton received a memo in February 1996 from John Huang, the Democratic Party’s key fund-raiser in the Asian community, reporting that his Asian contributors’ “top priority” was to kill this proposal. A month later Clinton told Congress that he favored retaining the sibling quota.

Meanwhile, Gimpel and Edwards report that a coalition of high-tech business leaders opposed to new restrictions on employment visas had visited every office on Capitol Hill. By the time Senator Simpson agreed to drop the proposed restrictions, the business community had formed an alliance with other pro-immigration groups and was committed to killing the entire bill. The high-tech lobby even hired Grover Norquist, a leading conservative lobbyist, to persuade Ralph Reed of the Christian Coalition that he should attack the bill as “anti-family.” Reed did this, allegedly because he wanted to solidify the Coalition’s alliance with the Catholic Church, which almost always opposes restrictions on immigration. In the end Congress made no major changes in the existing law.

The constellation of political forces that drove up immigration during the last third of the twentieth century could change in the years ahead. But while many writers say that immigration should be curbed, none has a politically plausible conception of how this might happen.

5.

America’s current immigration policy is a vast social experiment of the kind that Republicans normally detest. It involves two gambles. First, we are betting that rapid population growth will have no significant adverse effect on the quality of our descendants’ lives. Second, we are betting that we can admit millions of unskilled immigrants to do our dirty work without creating a second generation whose members will have the same problems as the children of the American-born workers who do such jobs.

The United States may be able to double its population without lowering the quality of its citizens’ lives, but the odds of its doing so would surely be better if it proceeded more slowly. The American labor force may also be able to assimilate the children of unskilled Mexicans, but again prudence suggests that we proceed slowly until we know more about how today’s Mexican-American children fare as adults. Finally, while the percentage of second-generation Latinos who have real difficulty understanding, speaking, and writing English may not be high, prudence suggests that we ought to be more certain about this before we commit ourselves to rapid growth in the Spanish-speaking population, since those who don’t learn English will not be able to make much progress in the larger society.

The Bush administration does not appear to be worried about any of these risks. Its main goal seems to be to please undecided Latino voters. It has floated a plan that would eventually legalize several million “undocumented” Mexicans currently working in the United States, as well as increasing the number of unskilled Mexicans admitted on a temporary basis. A new amnesty would surely help many of today’s illegals move to better jobs. But it will not eliminate the shadow economy in which illegals work, any more than the last amnesty did. As long as the legal risks remain trivial, some employers will prefer illegals to the available alternatives. And as long as illegals can find work, they will keep coming.

Border surveillance is likely to increase in the wake of the attack on the World Trade Center, but while Mexicans make up more than half of all illegal workers in the United States, monitoring the Mexican border is not an effective way to reduce American firms’ use of illegals. The INS thinks that it catches about a third of those who cross the border illegally. America could catch more people by spending more on the Border Patrol, but it is not clear how much difference that would make, because those caught crossing the border illegally are simply returned to Mexico, where they are then free to try again. Even if the Border Patrol caught two thirds of those crossing illegally, most job seekers would probably get across eventually. The only effective way to close the Mexican-American border (or any other) is to punish those who get caught, and that is not politically practical. Jailing illegals would cause a major row with Mexico. Perhaps even more important, it would almost certainly be unpopular with American voters as well. Americans see work as a moral virtue. They are unlikely to favor jailing people whose only sin is that they want a job.

In the long run, moreover, America’s best hope of reducing illegal immigration is to help create more jobs in Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean. For the foreseeable future, boosting employment in these countries depends heavily on making it easier for them to sell their products to Americans. Yet making it harder for Mexicans to cross the border illegally inevitably makes it harder to move goods across the border, because every truckload of goods could conceal illegal migrants. Instead of focusing on the border, therefore, it seems wiser to make hiring illegals both less profitable and subject to stronger penalties.

IRCA failed because it did not offer employers a simple, reliable way of determining workers’ legal status. Employers caught hiring illegals could claim that they had made a good faith effort to determine applicants’ legal status, and the courts generally accepted such claims. Creating a system for identifying people with a legal right to be in the United States is not technically difficult. Banks disburse billions of dollars in cash every day to customers who identify themselves with a piece of plastic and a code number. The federal government could create a similar system for identifying legal residents. The obstacle is not technical but political: employers, Latino activists, and some advocates of civil liberties all prefer a country in which employers can hire anyone they like, legal or illegal. Those who take this view will probably find themselves on the defensive in the months ahead, but unless mass murder becomes a regular part of our lives, libertarian principles will not go away.

The most politically promising way around this impasse is probably to seek a compromise like the one that Congress thought it was approving in 1986. Such a compromise would offer illegals already in the United States another amnesty but only if employers and Latino activists accepted a system that made identifying illegals easy and imposed serious penalties on any firm that hired them. Such a compromise would provide substantial legal, economic, and psychological benefits to millions of illegals currently living in the United States, many of them harshly exploited and living in miserable conditions. Those concerned about improving illegal immigrants’ lives would have good reason to support it. Devising an effective system for determining a worker’s legal right to be here would take some ingenuity, but the challenge is not insurmountable. Senator Alan Simpson’s proposal to experiment with secure drivers’ licenses almost passed in 1990. Making it harder to forge a driver’s license is not controversial, and indicating whether the driver is a legal resident of the United States is hard to portray as a major violation of civil liberties.

Some conservatives oppose such a compromise because amnesties for illegal immigrants encourage even more illegals to come. But a workable system for determining job applicants’ legal status should largely solve this problem. Some libertarians also oppose such a compromise, because they feel that the United States should admit any law-abiding individual who wants to come here. Indeed, some people think the United States should not only admit anyone who wants to come but offer them the full protection of American law and the American welfare state. But in a world where billions of people live close to starvation, no nation is rich enough to guarantee all its workers decent wages or working conditions unless it also limits the number of unskilled workers entering its labor market. Political support for both public education and the welfare state requires some sense of solidarity between haves and have-nots. Support for public education has already collapsed in California, at least in part because so many white California voters see the children in the schools as “them” and not “us.” Considerable support for the welfare state survives in California, but it has eroded in most other states where poor immigrants are numerous. Fifty years from now our children could find that admitting millions of poor Latinos had not only created a sizable Latino underclass but—far worse—that it had made rich Americans more like rich Latin Americans.

—This is the second of two articles on immigration.

This Issue

December 20, 2001

-

1

See “Who Should Get In?,” The New York Review, November 29, 2001.

↩ -

2

For a good review see Min Zhou, “Progress, Decline, Stagnation? The New Second Generation Comes of Age,” in Strangers at the Gates: New Immigrants in Urban America, edited by Roger Waldinger (University of California Press, 2001).

↩ -

3

Kristin F. Butcher and Anne Morrison Piehl, “Recent Immigrants: Unexpected Implications for Crime and Incarceration,” Industrial and Labor Relations Review, July 1998, pp. 654– 679. Although the Immigration and Naturalization Service can deport immigrants convicted of serious crimes, it hardly ever did this during the years covered by this study.

↩ -

4

The Japanese are an exception. Regardless of where Japanese mothers were born, their infant mortality rate is only two thirds that of non-Hispanic whites. See Nancy S. Landale, R.S. Oropesa, and Bridget K. Gorman, “Immigration and Infant Health,” in Children of Immigrants, edited by Donald J. Hernandez (National Academy Press, 1999).

↩ -

5

See Landale et al., “Immigration and Infant Health.”

↩ -

6

See the Rumbaut chapter in The Handbook of International Migration, p. 177.

↩ -

7

See National Center for Health Statistics, Health, United States, 2000 (Government Printing Office, 2000), p. 157.

↩ -

8

See UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre, “A League Table of Child Deaths by Injury in Rich Nations,” UNICEF, 2001.

↩ -

9

American ninth graders also use far more marijuana than those in Western Europe or Scandinavia, but they use no more than ninth graders in other English-speaking countries. This pattern also holds for LSD. See Manuel Eisner, “Crime, Problem Drinking, and Drug Use: Patterns of Problem-Behavior in Cross-National Perspective,” (Department of Sociology, Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, Zurich, 2000), Table 4.

↩ -

10

The teenage birth rate in the US is more than double that in Australia, Britain, Ireland, and New Zealand and six to fifteen times that in Western Europe. See Elizabeth Fussell, “Youth in Aging Societies” (Population Studies Center, University of Pennsylvania, 2000).

↩ -

11

Patrick Heuveline, “An International Comparison of Adolescent and Young Adult Mortality” (National Opinion Research Center, 2000), Table 8.

↩ -

12

For alcohol abuse, see Eisner, “Crime, Problem Drinking, and Drug Use.” For suicides, see Heuveline, “An International Comparison of Adolescent and Young Adult Morality.”

↩ -

13

1997 Statistical Yearbook of the Immigration and Naturalization Service (Government Printing Office, 1999), p. 141.

↩ -

14

The Handbook of International Migration, Tables 11.2 and 11.3. The data are for 1989.

↩ -

15

US Bureau of the Census, Statistical Abstract of the United States: 2000 (Government Printing Office, 2000), Table 54.

↩ -

16

See http://www.census.gov/population/ socdemo/race/interractab2.

↩ -

17

Statistical Abstract of the United States, 2000, Tables 1352 and 1361.

↩ -

18

See Smith and Edmonston, The New Americans, pp. 389–393.

↩ -

19

See Beck, The Case Against Immigration, pp. 65–71.

↩ -

20

The INS estimates that net illegal immigration (arrivals minus departures) averaged about 275,000 a year in the mid-1990s and that the number of legal immigrants returning home averaged about 200,000 a year. See 1997 INS Statistical Yearbook, pp. 199–203.

↩ -

21

The 1986 Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA) offered illegal immigrants a chance to become legal residents. About 2.6 million people took advantage of this amnesty between 1989 and 1993. The light solid line in the chart on page 95, which spikes during these years, includes these cases. Since 1994 official immigration statistics have underestimated the annual increase in the foreign-born population for a new reason. In 1994 the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) assumed responsibility for dealing with applications from people already living in the United States. It now has a backlog of about a million unresolved cases, most of which it expects to approve. These people already live in the United States, so I count them as if they were already permanent legal residents.

↩