1.

“For my dearest Vivienne, this book, which no one else will quite understand.” Thus Eliot inscribed a copy of his Poems, 1909–1925. One of his biographers asserts that

without knowledge of Eliot’s first, tragic marriage, a complete appreciation of his poems is impossible. No matter what Flaubert, Valéry, and Eliot may have said about the objective impersonality of art, the full heartrending meaning of The Waste Land and “Ash-Wednesday” depends on it.

Carole Seymour-Jones’s biography of Eliot’s first wife adds further notes toward the definition of her mysterious spouse, and explores a fresh cache of bisexual Bloomsbury gossip that amplifies the portrait of him. “Viv” predeceased “Tom” by eighteen years, a creatively fallow period also covered by the book but in less detail. Painted Shadow has been denigrated as part of a “campaign against Eliot,” but the campaign it exposes is the one to ignore his first wife, presented here as his troublesome muse. The new book disagrees on several points with Lyndall Gordon’s semi-authorized life of the poet,1 in which Vivienne has only half the index space given to Emily Hale, Eliot’s Bostonian friend whose in-person connection with him was immeasurably less than that of the tenacious Englishwoman with whom he managed to live for most of the time between their wedding in 1915 and separation in 1932. Vivienne, of course, does not really have a biography apart from Eliot. What the book offers instead is a surprisingly unexplored close-up perspective based in large part on Vivienne’s correspondence, contributions to The Criterion, writings still in manuscript, and unpublished diaries, of which only 1919 is complete for her married years.

Vivienne Haigh-Wood was born in 1888, four months before Eliot, in the Lancashire cotton mill town of Bury, to which her parents had journeyed from London for a one-man exhibition of her father’s paintings. He had studied at the Royal Academy School in London and become an Academician himself, and, born into a prosperous family, was not dependent on his art for his livelihood. His Anglo-Irish wife also had financial expectations, which must be said because Vivienne’s material position was superior to Tom’s, a calculated factor perhaps in their impulsive and clandestine marriage, which Eliot’s family opposed, as they did his choice of a possible career as a writer in England over that of a philosophy professor in America, for which he had been educated at Harvard. The nascent poet was obliged to accept support from, among others and most generously, his Harvard mentor and intellectual sponsor, Bertrand Russell, whom he had reencountered on a street in Oxford in October 1914.

The sexual and temperamental incompatibility of Vivienne and Tom is an overworked subject, but the book provides new material on this as well as on her background and childhood. As a young girl, Vivienne was subject to a variety of disorders, including tuberculosis of the bone, for which, apparently more than once, she underwent surgery. A more disruptive affliction was that of her too frequent, unpredictable, and painfully protracted menstrual periods, accompanied by abdominal cramps and severe mood swings. It is now thought that she suffered from a hormonal imbalance, curable today by the contraceptive pill, but whatever the cause, menstruation, the subject itself taboo at the time, was a torment for her, bringing on crying fits and disabling attacks of nerves. The drugs prescribed seemed to exacerbate her maladies, which in later years included colitis—“Tom,” Virginia Woolf thought, “was inclined to particularize the state of Vivienne’s bowels too closely”—neuralgia, migraines, and hallucinations of demons who emitted “groans, shrieks, and imprecations.” (Some of Vivienne’s best writing is in her descriptions of illness.) A victim of insomnia as well, she was dosed with bromides, chloral, and other addictive remedies.

That Vivienne was also intelligent and physically attractive is evident from her long love affair with Bertrand Russell. Though not educated to the highest levels, she had attended exclusive schools, was taken by her parents to France and Switzerland, and learned to speak fluent French. She met Eliot at an Oxford social function through a mutual American school friend and her current suitor, Scofield Thayer. Vivienne soon fell in love with the complex, shy, and silent Eliot, and he with her, but ambiguously. As all the world knows, the marriage, possibly never consummated,2was a disaster.

One of Seymour-Jones’s theses is that sexual and marital dysfunctions notwithstanding, Vivienne became both the source and the subject of some of Eliot’s greatest poetry, stimulating if not inspiring his creativity. As late as 1936, four years after the separation of the Eliots, Virginia Woolf, the first to perceive that part of The Waste Land is the autobiography of the marriage, admitted to Clive Bell that Vivienne was “the true inspiration of Tom”; but Virginia could also write cruelly about her: “Was there ever such torture since life began!—to bear her on one’s shoulders, biting, wriggling, raving, scratching…. This bag of ferrets is what Tom wears round his neck.” Bertrand Russell also realized this, observing that the couple were perfectly matched. As a prime source of succor to the Eliots through a long patch of their troubles, he came to the conclusion that “their troubles were what they most enjoyed.”

Advertisement

The book’s account of Vivienne’s collaborative assistance to Eliot in The Waste Land and her contributions, under aliases, to The Criterion holds some surprises. Eliot’s remark to his friend Sydney Schiff, in November 1921, on finishing a first draft of “The Fire Sermon” (The Waste Land) acknowledges the first part of this: “I do not know if it will do, and I must wait for Vivienne’s opinion.” This letter, sent from a clinic in Lausanne, also testifies that Dr. Vittoz, the psychiatrist and guru noted for his talent in achieving “transference” between therapist and patient,3 was succeeding in Eliot’s case. Vivienne, meanwhile, lived with the Pounds in Paris, where Ezra took her three times to visit Joyce, whom she described as “cantankerous, and wearing a long coat and tennis shoes.”

Vivienne either wrote the following lines from The Waste Land or is being quoted verbatim:

My nerves are bad tonight. Yes, bad. Stay with me.

Speak to me. Why do you never speak. Speak.

In view of them, her demand that Eliot delete the line “The ivory men made company between us,” as too revealing of their lack of communication, seems inconsistent.4 Though Pound cut most of Vivienne’s contributions to the poem, he retained her improvements to the Cockneyisms in the Lil/Albert scene, as well as the line, in her hand in the manuscript, “What you get married for if you don’t want children?” Vivienne is as central to The Waste Land as is the illusory Jean Verdenal (Phlébas le Phénicien), Eliot’s lost love.

Vivienne’s writings in The Criterion of 1924–1925 are a focal subject of the book. She chose the (arrogant) title of the magazine, helped to edit its contents, and to prepare each issue with her husband in their own home. Eliot wrote to Sydney Schiff, on February 24, 1924: “We have both been working at top pitch for the last five weeks to get out the Criterion.” She reviewed books, and published her poems, stories, and diaries, always under an alias, of which her favorite was “Fanny Marlow,” the surname being the residence that Russell had put at the Eliots’ disposal, the first name that of an anatomical feature of hers that enticed the great logician. To judge from the quotations in Painted Shadow, her best writing did not appear in The Criterion, but in the unpublished “Diary of the Rive Gauche,” an original and perceptive piece about an American in Paris. (Eliot’s own observations on Americans abroad—almost always “very immature”—are supercilious, as in a remark on seeing his old friend Conrad Aiken in London: “stupider than I remember him; in fact, stupid.”)

Vivienne’s verse is talented, but affected and tending to imitate her husband’s: “One’s soul stirs stiffly out of the dead embers of winter—but toward what spring?” Eliot’s defense of her work to The Criterion’s assistant editor Richard Aldington is convincing: “She is very diffident and very aware that her mind is untrained but she has an original mind. In my opinion a great deal of what she writes is quite good enough for The Criterion.”5 At this date (1924) she was an asset to him, not only by filling up columns of short reviews, but also, in Seymour-Jones’s words, by “sparkling at literary gatherings, where her spontaneity provided a refreshing contrast to the thrusts and parries of the literary-minded guests.” What disturbs us are the revelations that Vivienne ghost-wrote “On the Eve,” which appeared in the January 1925 Criterion under her husband’s name, and her confession in a 1924 letter to Pound that she had written “nearly the whole of the last Criterion.”6

Vivienne’s symptoms of growing mental instability began to increase at the beginning of the 1930s, together with a penchant for humiliating Eliot in public. W.H. Auden used to tell a story of arriving at the Eliots for dinner in 1932, and being received by Vivienne, saying “We are very pleased to be here, Mrs. Eliot,” and of her response: “Tom’s not pleased.” At one dinner party, according to Seymour-Jones, “both Eliots directed streams of hatred at each other throughout the meal,” until embarrassed guests began to depart. “‘There is no such thing as pure intellect,’ Eliot declared. Vivienne interrupted angrily: ‘What do you mean? You know perfectly well that every night you tell me that there is such a thing: and what’s more that you have it, and that nobody else has it.'” Eliot fought back with “You don’t know what you’re saying.” Conrad Aiken, who was present, later reported that “Vivienne did not appear mad to me.”

Advertisement

The final chapter of Vivienne’s life is both the climax of the book and a complete blank: her nine-year incarceration in an insane asylum. In July 1938, the police found her wandering in a London street at five in the morning and in a state of considerable mental confusion, saying that she was hiding from mysterious people and had heard that “Tom had been beheaded.” Her brother, Maurice Haigh-Wood, came to fetch her and to obtain a magistrate’s warrant for her commitment to Northumberland House Insane Asylum. Maurice informed Eliot, who, not so coincidentally, perhaps, was vacationing with Emily Hale in Gloucestershire, but he refused to come to London or to share the responsibilities. Maurice recounted the full proceedings to Michael Hastings, author of the play Tom and Viv, on several occasions in 1980. The following excerpt calls Eliot’s involvement into question:

It was only when I saw Vivie in the asylum for the last time I realized I had done something very wrong. She was as sane as I was. I did what I hadn’t done in years. I sat in front of Vivie and actually burst into tears…. What Tom and I did was wrong…. I did everything Tom told me to….

Together with two doctors who did not know Vivienne and, the author suspects, may have been on the institution’s staff, Maurice signed the certification papers. But it was clearly Eliot’s wish to eradicate Vivienne from his life, and, as Maurice implies, Eliot instigated the action.7 In 1932, when Eliot was invited to give the Norton Lectures at Harvard, Vivienne accompanied him to Southampton but not to America. Months later he wrote to his London solicitor asking him to obtain a legal separation from her on grounds that she had become a nuisance and embarrassment to him. On his return to England in the summer of 1933, when he and Vivienne met in the solicitor’s office to sign papers, she held his hand but he would not look at her. Henceforth he went into hiding, constantly changing addresses to avoid her, and refusing to receive her at his Faber office.

She encountered him once more, however, at the Sunday Times Book Fair in Lower Regent Street on November 18, 1935, as he was walking to the platform to give a lecture. “Tom,” she said, whereupon he seized her hand and said, “How do you do,” loudly, so that anyone overhearing would suppose this to be a first meeting. Then grotesquely she stood next to him on the platform throughout the lecture wearing her recently acquired British Union of Fascists uniform, a black tam and black macintosh. This must have enraged Eliot, who detested Oswald Mosley, and the poet would have been appalled if he had followed Vivienne’s invitation to come home with her, where he would have found Sir William Rothenstein’s portrait of Mosley in the drawing room.

The biographer believes that Vivienne’s condition neither necessitated nor justified permanent confinement, severed from all contact with the outside world. She had been a patient in a sanitarium for nervous disorders in Malmaison, France, on two occasions, one of them jointly with Eliot, twice discharged as stabilized. She seems to have been treated well there and much liked, and the same was true of the Eliots’ stay together in June 1927 in an establishment for mental disorders at Divonne-les-Bains, near Geneva (not mentioned in Painted Shadow). An alternative was that Vivienne’s family inheritance, administered by Maurice and Eliot, was substantial enough to have made home care an option. Eliot’s widow, Valerie, has testified that “restraints were sometimes necessary,” and at least once Vivienne had attempted to escape.

Eliot seems to have made no inquiry regarding the conditions of Vivienne’s care and well-being.8 He did not contact her—her letters to him at Faber were returned unopened—but he must have heard something about her from Enid Faber, wife of the publisher, who visited her faithfully throughout the war, though no word of these meetings has ever appeared in print. Seymour-Jones suggests that Vivienne may have committed suicide with hoarded pills, difficult as that would have been under close surveillance. But the thought makes the reader wonder what happened to the drug dependencies and the ether,9 which, years before her commitment, had been supplied daily by her family physician. The book does not mention medications, drug withdrawals, or indeed anything else about the life of the inmate.

2.

Seymour-Jones assembles a parallel portrait of Eliot during the Vivienne years and a bit beyond. One of the first glimpses is via the chatelaine of Garsington, Lady Ottoline Morrell, the granddaughter of a sister of Queen Elizabeth’s grandmother and the wife of Philip Morrell, a wealthy member of Parliament (who fathered a son on his secretary, and another one on his wife’s parlormaid). Ottoline Morrell met the young poet through her lover, Bertrand Russell. She nicknamed Eliot “the Undertaker,” and said he was “dull, dull, dull”:

He never moves his lips but speaks in an even and monotonous voice, and I felt him monstrous without and within. Where does his queer neurasthenic poetry come from, I wonder…. I think he has lost all spontaneity and can only break through his lock up by stimulants or violent emotions…. He was better in French than in English. He speaks French very perfectly, slowly and correctly.

On another occasion she thought his “carefully enunciated English sounded false,” but as Dame Helen Gardner observed, “he lost his American accent without ever developing English speed and English slurring and English speech rhythms.” Osbert Sitwell was “struck by the contrast between his diction, the slow, careful, attractive voice, which always held in it, deep and subjugated, an American lilt and an American sound of r’s.” Russell thought that Eliot’s “slowness is a sort of nervous affliction. It is annoying—it used to drive his wife almost to physical violence—but one gets used to it.”

Of their first meeting, November 15, 1918, Virginia Woolf recalled a patrician, a “polished, cultivated, elaborate young American.” Before long, she discovered that he was also “sinister, insidious, eel-like.” By August 1922, he was perceived as “sardonic, guarded, precise, and slightly malevolent…,” and Virginia confessed to “growing boredom with his troubles and his tedious and longwinded American way…. I could wish that poor dear Tom had more spunk in him, less need to let drop by drop of his agonized perplexities fall ever so finely through pure cambric.” When ruffled, “he behaves like an old maid who has been kissed by the butler.” Mrs. Woolf’s dislike grew when she became aware of his hypocrisy. She had seen a performance of King Lear with him, at which they both “jeered,” but which Tom praised as “flawless” in the next Criterion. A crisis occurred when he took The Waste Land and other poems away from the Woolfs’ Hogarth Press and furtively placed them with his new company, Faber. She thought that Tom had treated her and Leonard “scurvily…. Leonard thinks the queer, shifty creature will slip away now.” Eliot’s conversion truly horrified her—“most shameful and distressing…. Tom Eliot may be called dead to us from this day forward. He has become an Anglo-Catholic, believes in God and immortality, goes to church….10 There is something obscene about a living person sitting by the fireside and believing in God.” She would have endorsed Harold Bloom’s “To have been born in 1888 and to have died in 1965 is to have flourished in the age of Freud, hardly a time when Anglo-Catholic theology, social thought and morality were central to the main movement of mind.”

In March 1929, at age forty, Eliot took the Church’s “vow of chastity,” which sounds like making a virtue of necessity. (But why did it seem necessary to proclaim this private matter in a public document, unless he was attempting to nullify his marriage, the vow constituting a diriment impediment?) The “King Bolo” verses, published (incomplete) in the volume edited by Christopher Ricks, Inventions of the March Hare: Poems 1909–1917, bring Eliot’s sexuality to the surface, though they trouble us as much for the substandard quality of some of the verse as for their adolescent ribaldry. Why, one wonders, was Eliot eager to preserve them, since they reveal so much of what he wanted to hide?

Seymour-Jones’s depiction of Eliot as having homosexual tendencies is incontrovertible, but she omits the most important bit of evidence for it, the verse that Ezra Pound, who probably knew more about Eliot’s sex life and inclinations than anyone else, sent to him after reading The Waste Land:

These are the poems of Eliot

By the Uranian muse begot.

(Perhaps the word was better known then than now, owing to Wilde’s “To have altered my life would have been to have admitted that Uranian love is ignoble.”) Was Eliot a practicing homosexual? The book’s chronicle of his activities in this regard from the mid-1930s is scarcely believable and, indeed, presents no real evidence, but only the comings and goings of younger men to his apartment. Eliot had certainly fallen in love with Jean Verdenal in Paris in 1910–1911, but even the author thinks that, given Eliot’s inhibitions, “the relationship with Verdenal…was unlikely to have been a physical one, notwithstanding the constant homosexual theme of the [Bolo] verses.” The prayer concluding “Ash-Wednesday” (“Spirit of the river, spirit of the sea…”) invokes Verdenal, not Vivienne, the original dedicatee, as, of course, do the three mentions of Phlebas, all of them mistaken in that Verdenal’s war record makes clear he did not drown while standing in waist-high water off a landing beach in the Dardanelles helping to evacuate soldiers, but died later, while attending a wounded man on a battlefield on May 2, 1915. Yet how do we explain Eliot’s tantrum in 1952, forcing the publisher of an essay that speculates on the nature of the Verdenal friendship to withdraw it? Eliot’s outraged response seems out of proportion to an untruth.

Eliot’s ability to terminate relationships with the people closest to him is yet another enigma of his character. Seymour-Jones notes that he “abandoned” John Hayward, his muscular dystrophic housemate of eleven years, “with the same abruptness and moral cowardice with which he left Vivienne.” In Hayward’s version, Eliot entered his room early on January 10, 1957, and asked him to read a letter that he handed to him announcing his immediate departure and imminent elopement with his young secretary. Hayward read it and said that he was not angry, whereupon Eliot leaned forward, put his arm around him, and kissed him. (Hayward later recorded that “since I am the most un-homosexual man in London, I found this a most offensive gesture.”) But why, after the marriage, did Eliot sever relations11 with this trusted friend and respected literary scholar who had helped him with critical advice in the composition of Little Gidding? Not long before, Eliot had chosen him as his literary executor, instructing him that “I don’t want any biography written or any intimate letters published…. Your job would be to discourage any attempts to make books of me or about me, and to suppress everything suppressible.”

Both Emily Hale and Mary Trevelyan, a close London friend from the late 1930s, had thought of themselves, not without justification, as “fiancées presumptives.” Eliot seems to have given Emily reason to believe that he would marry her if Vivienne were to die, and when the poet’s brother wrote to ask if there was any basis to this, the reply was affirmative. Emily had accompanied Eliot on his visit to Burnt Norton in 1935, but neither of them attached any significance to this. Back in Boston, after Vivienne’s death, Eliot told Emily that he could not marry her, but the news of his nuptials to Valerie came as an immense shock to her. When Emily deposited at Princeton the thousand or so letters he had written to her over a period of fifty years, and she wrote to him offering to “excise” any intimacies in them, he ignored her letter and placed an interdiction against all accessibility until 2020. When she wrote to say that Princeton wanted him to reduce the time of the ban, he again did not answer but vindictively burned all of her letters to him.

The relationship with Mary Trevelyan was more intimate, since they saw each other for dinner or drives in the country regularly for twenty years. She was a confidante of Hayward’s as well, trying, with him, to protect Eliot from the impression of arrogance and omnipotence that he had begun to make. In 1955 she wrote to Hayward concerning the deification: “I have noticed of late his immense indignation with anyone who disagrees with him.” In 1958 she wrote angrily that “Tom is a great ‘runner-away.’ He is extremely deceitful when it suits him and he would willingly sacrifice anybody and anything to get himself out of something which he doesn’t want to face up to.” After Eliot’s remarriage, Mary sent two letters conveying every good wish to him in his new life, and received an outraged reply accusing her of “gross impertinence.”

Painted Shadow tells us that “the intimate letters between Pound and Eliot” of the early 1930s reveal a “shared anti-Semitism” and may help to explain why successive volumes of Eliot’s letters have not followed the one that appeared on his centenary, September 1988. Painted Shadow does not dwell on the issue; and says more about his Jewish friends, Leonard Woolf, Sydney and Violet Schiff (in whose house Eliot met Frederick Delius), and Margaret (Margot) Cohn, owner of House of Books on Madison Avenue, a good friend of T.S. and Valerie Eliot, who stayed with her in her Manhattan apartment during five of their New York sojourns. But nothing at all is said about Eliot’s relationship with the sculptor Sir Jacob Epstein and his wife, close friends, concerning whom the reader would like to know more.

Seymour-Jones quotes part of Isaiah Berlin’s 1951 letter to Eliot protesting the infamous passage in After Strange Gods, showing Berlin to be more hurt than indignant by the asperity of Eliot’s intolerance. He quotes the poet’s own words back at him to the effect that “reasons of race and religion make any large number of free-thinking Jews undesirable”:

You thought it a pity that large groups of “free-thinking Jews” should complicate the lives of otherwise fairly homogenous Anglo-Saxon Christian communities? And that it were better otherwise?… And that it would be better for such communities if their Jewish neighbours…were put “beyond the borders of the city”?

Eliot responded that “the sentence of which you complain would of course never have appeared at all…if I had been aware of what was going to happen, indeed had already begun in Germany.” Yet by 1934, when the book appeared, everyone in the literate world could see what was happening. Late in life Eliot discontinued publication of After Strange Gods, but refused to delete the contemptuous references to Jews in reprints of his collected poems, or even, in one instance, Gerontion, to change the spelling of the word from lower to upper case.

Errors, obscurities, and omissions of significant aspects of Eliot’s history are by no means rare in Painted Shadow. As an instance of its errors, Seymour-Jones introduces a “Princesse di [sic] Bassiano,” apparently unaware that “Bassiano” was the American-born Marguerite Chapin, publisher of the Botteghe Oscure, wife of Roffredo Caetani, Prince of Bassiano, and a cousin of Eliot’s on his mother’s side. Nothing is said about his longest work in verse, the translation of St. John-Perse’s Anabase, and Perse himself, a close friend, is not even mentioned. Another omission is of the role of Robert Sencourt, the only friend to have been a houseguest of the Eliots at Clarence Gate Gardens near the end of their marriage, a development that Sencourt foresaw, wondering how the two could have stayed together at all, and concluding correctly that they were already leading secret lives apart. He describes Vivienne as “wayward, unpredictable, finding fault in everything, subtly thwarting Eliot at every turn.”

Djuna Barnes merits more space than the three brief references to her suggest. Seymour-Jones misses an opportunity to use this patroness saint of lesbianism to support the idea that Eliot’s attraction to masculine women was another aspect of his sexuality. Barnes became a cherished friend of the poet, whose letters address her as “Darling” and “Dearest.” When she told him that she had “wasted her life,” he answered gently that she “may have wasted some of it, but she should look very carefully at what she had done when [she] was not wasting it,” meaning her novel Nightwood, which he published and made famous in a preface to the American edition. (Another publisher had rejected it because of the “welter of homosexuality.”) One supposes that her conversation amused him, viz.: “Everyone hates old ladies because they aren’t good for anything. They aren’t pretty and they can’t screw.” Eliot did not like her play Antiphon, no doubt for the reason that, as Seymour-Jones recognizes, it is “the revenge drama Djuna Barnes wrote after seeing Eliot’s Family Reunion.” He published it, nevertheless. Barnes herself always thought his criticism superior to his poetry.

Eliot’s biographers have little to say about Prince D.P. Svyatopolk-Mirsky, the intellectually distinguished White Russian who was a frequent Eliot visitor in the 1920s and early 1930s. In 1924 the Woolfs published the Autobiography of the Archpriest Avvakum, with Mirsky’s introduction claiming this seventeenth-century life as the most significant work in Russian literature between the twelfth-century’s Lay of Igor and the late-eighteenth-century odes of Lomonosov. Eliot probably read it, however, for the reason that one of its translators was a longtime friend, Hope Mirrlees, in whose family home at Shamley Green, Surrey, he resided for part of each week during most of World War II.

One useful book by Eliot remains unpublished, a sampling of his work as a Faber publisher and editor, including his “blurbs,” one of which was for The Tropic of Cancer. To judge by the wise and witty fragments that have appeared in the catalog of the Humanities Research Center at the University of Texas, Austin, these may be his most interesting letters. The present writer is indebted to Margot Cohn for the following excerpt from a letter of Eliot’s to Allen Tate, August 19, 1943, on the reasons for rejecting some poems by the young Robert Lowell, over which Eliot says he has “brooded” for four months:

…I don’t feel that his religious convictions have yet sunk down through the surface to that unconscious level of experience which I think such convictions have to reach to rise again as material for poetry. Something similar seems to be lacking still in his verse as poetry. I don’t think he has altogether assimilated his models, and his words in general seem a little self-conscious, but I would like to hear more of him from time to time as he is obviously something out of the ordinary.

Another wished-for volume is an Eliot lexicon containing all those words that no one will dare to use again—“velleities,” for one—and compiling his contributions to the Revised Psalter of the Book of Common Prayer. (In the Twenty-Third Psalm, Eliot insisted on retaining the phrase: “Though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil,” despite the Hebrew original’s limitation to “the valley of deep darkness.”) If one agrees with Martin Amis that “just because Eliot’s plays don’t work in the theatre does not mean that they are any fun to read,” the poet’s last work of value was his part in preserving Coverdale’s text. Eliot lambasted the concurrent publication of The New English Bible, objecting to the updating of “bear the burden of the heat of the day” to “sweated the whole day long in the blazing sun,” and of “neither cast ye your pearls before swine” to “do not feed your pearls to pigs,” on grounds that “swine” is still in common usage as an insult, and that the nourishment of the animal is not the point but its inability to appreciate beauty.

Not far into the future, one hopes, when the Eliot biography is completed, and placed on a hard-to-reach shelf, Eliot the poet, with the keenest ear in modern literature, will prevail.

This Issue

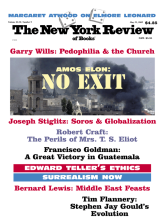

May 23, 2002

-

1

T.S. Eliot: An Imperfect Life (Norton, 1999).

↩ -

2

Logan Pearsall Smith maintained that “Eliot had compromised Miss Haigh-Wood and then felt obliged as an American gentleman, the New England mode being stricter than ours, to propose to her.”

↩ -

3

This was the opinion of Julian Huxley, who had been a patient of his the year before.

↩ -

4

Eliot restored it from memory in 1960.

↩ -

5

Aldington, almost alone, recognized Eliot’s The Sacred Wood (1920) as “the most original contribution to our critical literature during the last decade.”

↩ -

6

Vivienne’s papers were deposited at the Bodleian Library in 1947 by her brother, but the black notebook containing the drafts of her stories, often edited in T.S. Eliot’s hand, has been missing since 1990.

↩ -

7

In 1944 Eliot told Mary Trevelyan that it was at his instigation that Vivienne had been made a Ward of Chancery, and that because of the “V2 bombs” he had tried to arrange for her to be moved to an institution farther from London, but Maurice’s permission was necessary and he was unreachable with the British army in Italy.

↩ -

8

On hearing the news of Vivienne’s death, in January 1947, Eliot told Mary Trevelyan that it was “unexpected. She was supposed to be in quite good physical health.”

↩ -

9

Maurice denied that she ever took ether, but Virginia Woolf detected it, and Aldous Huxley told this reviewer that at times the Eliot house “smelled like a hospital.” Cyril Connolly testified, in the London Sunday Times, November 7, 1971, that Leonard Woolf had told him Vivienne was addicted to ether.

↩ -

10

In a Christmas letter to Harriet Shaw Weaver, Joyce took a more amused view of the conversion: “Eliot is dusting pews in an Anglo-Catholic church round your corner. Ask him to have an A.-C. mass said for the three Joyses.”

↩ -

11

In truth, Eliot invited Hayward and Rosamond Lehmann to a lunch for Robert Frost, which is curious in itself, in that Frost had publicly disputed a statement in one of Eliot’s Harvard lectures. Hayward did not hide his irritation with Eliot at the repast but returned the invitation, which Eliot honored. In the 1963 reprint of Four Quartets, Eliot removed a note of acknowledgment to Hayward that appears in the original.

↩