“Just when we thought we’d recovered an environment that made it possible to live in peace, they answered: Here, take your dead man, who tried to discover the truth.”

—Bishop Ríos Montt, head of the Guatemalan Archdiocese’s Office of Human Rights (ODHA), at the trial of the accused murderers of his predecessor, Bishop Juan Gerardi

1.

Last June 7 three military men, two of them officers, were convicted in a Guatemala City courtroom of having participated in a military intelligence unit’s brutal, politically motivated murder—“extrajudicial execution” was the legal term used—of Bishop Juan Gerardi Conedera, the founder and director of the Guatemalan Archdiocese’s Office of Human Rights (ODHA). A parish priest was also convicted as an accomplice in the crime. It was a verdict that most Guatemalans had never expected to hear, at least not yet, and certainly not in relation to this crime.

Until June 7, no military officer had ever been found guilty and sentenced to prison in Guatemala for a political murder—one commissioned and carried out with the help or acquiescence of a state institution (the military, in particular)—even though, over the last quarter-century especially, the military amassed a record as the hemisphere’s greatest violator of its citizens’ human rights, responsible for the murder of as many as 200,000 unarmed civilians. Also unprecedented was the inclusion in the judges’ verdict of an order for a criminal investiga-tion against the likely “intellectual authors”—i.e., planners—of the crime: the commanding officers of the convicted soldier’s military unit, implicated during the trial in Bishop Gerardi’s murder.

For over three years incidents of intimidation and threat marked the prosecution of the bishop’s murderers. Before the trial began over a year ago, a judge, a government prosecuting attorney, and several key witnesses had to go into exile; intruders entered the home of Mynor Melgar, the head of ODHA’s legal team, which was helping to prosecute the case, and, in front of his wife and small children, forced him to kneel on his bathroom floor with a pistol held to his head, then told him it was just “a warning.” Indeed, the trial’s scheduled opening in March 2001 had to be postponed after two grenades exploded in Judge Yassmín Barrios’s backyard. Throughout the trial, the Public Ministry’s prosecuting attorney, Lepoldo Zeissig, his wife, and his infant child were forced to live like protected witnesses in a drug lord’s case, and, after the verdict, were finally driven by threats to go into exile.

Since the trial, the defense has waged an even more relentless campaign in the press to undermine the verdict. They have accused the judges of corruption and of having yielded to the pressures of foreign governments,1 and have accused the witnesses—most of them members of the underclass—of having sold their testimony for the supposed financial benefits of exile. Capitalizing on much of the confused reporting of a complex and largely circumstantial case, and on the public’s cynicism about government institutions generally, the defense lawyers have succeeded in creating a climate of popular opinion that could provide sufficient cover to any judge who might overturn the convictions on appeal.

In 1996, when the thirty-six-year civil war was finally ended by UN-brokered peace accords, the UN and the EU, along with the US and several nongovernmental organizations, joined in the enormous task of helping a traumatized Guatemalan society maintain that peace. They intended to “build democracy” while participating in the country’s debate over how to deal with human rights crimes of the past.

Successfully bringing the Bishop Gerardi murder case to trial was an important result of this debate. The new president, Alfonso Portillo, who took office in January 2001, had promised in his election campaign to resolve the Gerardi case; however, once he took office he did not even share with the prosecution the results of his government’s internal investigations into the crime. Nevertheless, he has tried to take credit for the convictions. However courageous and persistent many Guatemalans—especially the young activists of the bishop’s ODHA group—were in pursuing the case, without the constant monitoring and sometimes direct intrusion of MINUGUA, the UN peacekeeping mission, and pressure from several foreign governments, including the United States, it is doubtful that the trial could have taken place at all. Whatever the final outcome of the forthcoming appeal, it gave Guatemalans for the first time an account of the inner workings of Guatemala’s army covert intelligence units, which for decades have spread terror throughout the country.

2.

On the Sunday night of April 26, 1998, just before ten, after returning from dinner with relatives, Bishop Juan Gerardi, a robust seventy-five-year-old, had driven himself back to the San Sebastián Church parish house, in the old center of the city near the official presidential residence and the former National Palace. Moments after pulling his white VW Golf into the garage, a swift and brutal beating left him lying dead on the floor, his skull shattered. Ten or so minutes later a homeless man, one of about a dozen who regularly slept in front of the parish house garage, saw a bare-chested young man step out through the garage’s small side door. Known as el hombre sin camisa, the man without a shirt, he left a blue sweater behind on the garage floor and a large, rough-edged triangular chunk of concrete, the presumed murder weapon, in a pool of blood.

Advertisement

The shirtless man disappeared after the murder, and has never been caught. But by the end of the trial, several witnesses identified him as “Hugo,” a former Guatemalan special forces soldier and agent of G-2 military intelligence, in the occasional employ of the Presidential High Command, or EMP, a unit based just blocks from San Sebastián Church. Two of the three military men convicted, Captain Byron Lima Oliva and Specialist José Obdulio Villanueva, had belonged to that unit, which is responsible for guarding the president’s security, among other tasks. The EMP, which has always had its own intelligence unit, formerly known as the Archivo, but now considered subordinate to Guatemalan army intelligence (G-2), has been suspected of many assassinations and disappearances during the 1980s and 1990s.

Two days before his murder, Bishop Gerardi had made public Guatemala: Never Again, a four-volume report on the civil war’s atrocities that was produced by the Interdiocesan Project for the Recuperation of Historical Memory (REMHI). It was compiled from testimony gathered mainly by Church volunteers throughout the country and documentary sources such as declassified US State Department documents. The report identified by name more than 52,000 of the war’s estimated 200,000 civilians killed or disappeared, and it concluded that the Guatemalan army was responsible for some 80 percent of those deaths, the guerrillas less than 5 percent.

In the report’s 1,400 pages, the human voices of the Guatemalan tragedy are preserved as they are nowhere else. According to a former Peruvian general, Rodolfo Robles Espinoza, an expert on the military in Latin America, who testified for the prosecution during the trial of the bishop’s murderers, REMHI painted a picture of “a genocidal army” that, during the 1980s especially, had gone on a rampage of massacres against the rural Mayan population, while routinely murdering, disappearing, and torturing civilians it saw as political opponents.

According to Edgar Gutiérrez, the former director of REMHI and a protégé of the bishop—now working as the head of the Office of Strategic Analysis in President Portillo’s government—Gerardi had initiated REMHI largely because he knew that the imminent signing of the peace accords was going to result in a UN-sponsored truth commission. Gerardi understood that most Mayan villagers wouldn’t feel secure cooperating with UN investigators unless the Catholic Church could dispel some of their fears about speaking out, and help prepare for the second, more ambitious, project. The bishop had also let it be known that evidence collected by REMHI would be available to people who might later seek justice against either the military or the guerrillas. Thus an obvious motive for the murder was to punish Bishop Gerardi for publishing a report that could ultimately threaten the military’s immunity from prosecution for such crimes, and to issue a warning against following his lead. Gutiérrez and others at the ODHA maintained that the elaborately staged murder was also a scheme to divert attention from the report to a scandal-tinged mystery and media circus. In this they succeeded.

When the huge UN-sponsored report Memorial of Silence was released in 1999, a year after the REMHI report and the bishop’s murder, it presented an even darker picture, finding the military responsible for more than 90 percent of civilian deaths, and formally charging the Guatemalan army with genocide against the rural Maya. Under the peace accords, both sides had agreed to a general amnesty from prosecution for war crimes. But under international law, there can be no amnesty for crimes against humanity, such as genocide. That law cleared the way for many of the court cases which have since been initiated in Guatemala.

Bishop Gerardi founded the ODHA in 1986. It was the first human rights center in Guatemala capable, through the Catholic Church’s diocese network, of providing legal services, protection, and educational programs to human rights workers throughout the country. Since the peace accords were signed, the ODHA has been providing psychological counseling to victims of violence and participating, along with other organizations, in the excavations of massacre sites.

The ODHA’s mostly secular staff of lawyers, psychologists, and anthropologists work in a two-hundred-year-old Spanish colonial-style building next to the Metropolitan Cathedral, adjacent to the former National Palace and just a few blocks from San Sebastián Church. On April 26, as soon as they heard about the bishop’s murder, some of the ODHA’s younger activists rushed over to San Sebastián Church, where a crowd had already formed and was walking around the body in the garage and in and out of the parish house. From the start, they could hardly expect much in the way of useful forensic evidence to emerge from such a contaminated crime scene. They also assumed that the police and Public Ministry investigation of the bishop’s murder would not go after the most obvious suspects, the army or people with ties to it. They decided to document the murder investigation on their own. The team that worked with the ODHA’s lawyers consisted of four university students, only one of them with experience in criminal investigations.

Advertisement

Jokingly calling themselves Los Intocables, they initially saw their role as defensive: they would try to learn enough to refute any false evidence that might be put forward during the investigation. But useful information about the crime, much of it anonymous, flowed through the ODHA anyway, and soon they found themselves at the forefront of the most publicized and politicized legal battle in Guatemalan history.

3.

Some of the most powerful evidence, the ODHA investigations began to see, pointed to Captain Byron Lima Oliva, a young aide-de-camp in the EMP’s elite Presidential Guard, and to his father, Colonel Byron Lima Estrada, who had commanded troops in some of the most violent theaters of the war, and who in the mid-Eighties was named the head of the Guatemalan army’s main intelligence section (the G-2). Colonel Lima was regarded as a leader of a powerful group of retired officers and war veterans who continue to wield power within the military, and are among the most vulnerable to pros-ecution for past human rights–related crimes.

Guatemalans become rich in the military, often through such activities as narcotics trafficking and auto theft. Recent civilian presidents, including Portillo, have been unable to force the military to relinquish its control over internal national security, that is, intelligence, as mandated by the peace accords. Early in the trial, Edgar Gutiérrez testified that a few weeks after the bishop’s murder, he and other ODHA members had asked the government to look into the participation of both Limas. An aide to then President Álvaro Arzú had answered that they couldn’t investigate the President’s security personnel because to do so would be to “bring the game to”—i.e., antagonize—“the Cofradía.” The Cofradía, the name given to religious brotherhoods in Guatemalan folk religion, is a group of active and former soldiers created at the end of the Seventies inside military intelligence. According to Gutiérrez, “Military and paramilitary structures became accustomed to working with total impunity. Civilian governments weren’t capable of dismantling them. Because this impunity protects them, it intimidates and prevents anyone from denouncing them.”

Another reason for Bishop Gerardi’s murder was also given: if the REMHI report’s conclusions led to prosecution of the military for past crimes, then it could also loosen the military’s hold on real power, on the state’s overdeveloped intelligence apparatus, and on criminal rackets, which all depend on their being able to commit crimes without fear of going to prison.

The first chief prosecutor appointed to the investigation by the Public Ministry was Otto Ardón, a former lawyer for the Guatemalan air force. Ardón proposed that the murder was a domestic crime involving another priest. He was careful not to call it a homosexual crime out of fear of inflaming Catholic sensibilities, but that was widely inferred. When a top-ranking military officer said the murder had resulted from a fight among homosexuals, the charge was soon echoed by a leading conservative columnist in the nation’s largest newspaper, and then widely repeated. This led to the arrest in July 1998 of the sickly thirty-four-year-old Father Mario Orantes, who had shared the San Sebastián parish house with Bishop Gerardi. Along with other pieces of evidence, the priest’s contradiction-filled and implausible accounts of his behavior put him under suspicion.

Nobody at the ODHA thought the somewhat sybaritic priest—his bedroom in the parish house turned out to be an Imelda Marcos–like lair with luxurious designer clothing, an expensive TV set, and a 9mm Walther pistol—murdered the bishop, but they did suspect him of complicity: of being too ashamed or terrified to admit to being a willing conspirator, or being coerced or entrapped by those responsible for the murder. He may, for example, have opened a door to let the assailants in or out. Neither the ODHA nor the prosecutors believed the priest when he said that he remained in his bedroom and did not notice anything during the crime, and then that he was shocked to find the body lying in a pool of blood in the nearby garage. And though the garage was well-lit, he claimed he didn’t recognize the body as that of Bishop Gerardi, his housemate of eight years.2

The faked charge of “crimes of passion” has long been used to explain assassination in Guatemala. Ardón rejected Orantes’s account and proposed instead that during the fatal argument in the garage the priest had sicced his German shepherd, Baloo, on the bishop. An eccentric forensic anthropologist in Spain, from photographs, identified wounds on the bishop’s head as dog bites. But the ODHA introduced its own experts from the United States, including the forensic dentist and FBI consultant who had been called in at the trials of Jeffrey Dahmer and Ted Bundy. He testified that Bishop Gerardi had probably been attacked by at least two assailants, including one who had struck him across the front of the face with an object like a steel pipe.

In March of 2001, when the Bishop Gerardi murder trial finally got underway, many of the important prosecution witnesses had left the country because of threats and intimidation; others peripherally connected to the case, who might have been able to corroborate aspects of other testimony or even provide new information, had been murdered or had died in suspicious ways, including many of the indigents, los bolitos, known to each other by such names as “Lollipop,” “The Monster,” “El Chino,” and “Roast Meat,” who’d regularly slept in front of the San Sebastián parish house garage, and were there on the night of the murder. They may have been drugged that night by someone who left them food and open quart bottles of beer. This would explain why the indigents slept like stones through the night, and why only Rubén Chanax Sontay, the indigent informer who would emerge as a key witness, and who did not drink beer, remained awake.

As in most developing countries, Guatemala’s crime laboratories lack the resources for doing reliable forensic studies. The ODHA’s lead lawyer, Mynor Melgar, told me, “Usually the only real evidence you can take to trial is the testimony of witnesses. And people can buy witnesses, intimidate them, they can kill them. And that is what makes trying cases in Guatemala very complicated.” This was certainly true of the Gerardi murder trial, which depended almost entirely on witnesses. Nevertheless witnesses’ testimony gave a fairly continuous account of the crime. They included a taxi driver, since living in exile, who had driven past the church just after the crime and seen a shirtless man with what appeared to be a tattoo on his arm standing by a white Corolla, while other cars sped past him the wrong way down a one-way street. Because, as a drug user, the taxi driver was always watching out for the police, he’d memorized the Corolla’s license plate number, 3201, which was later traced to the Ministry of Defense; a few years before, the plates had been assigned to a military base there under the command of Colonel Byron Lima.

The second key witness for the prosecution was a thief, Gilberto Gómez Limón, who in 1998 had been imprisoned along with Specialist José Obdulio Villanueva, the third military defendant, who belonged to the same unit, the EMP, as Captain Lima. Gómez Limón was serving a sentence of two and a half years in the same Guatemalan prison, in Antigua—a half-hour or so drive from the capital—as Specialist Villanueva, who was serving a two-month sentence for killing a milkman who’d unwittingly driven his truck into the path of then President Arzú. Gómez Limón knew that Villanueva had worked as the President’s bodyguard, and he told the court that the day Villanueva had entered the prison to serve his term, the authorities had warned him: “Don’t touch him in any way, because he works for the State.”

Gómez Limón described how he observed Villanueva leave the prison—as inmates who paid off guards could easily do—at 5:30 on the morning before the murder, return for roll call at 5:30 that evening, and then disappear once more during the night when the murder occurred. After he came back to the prison at dawn, he was, Gómez Limón testified, anxious to see the morning television news:

“A la gran chucha! It’s time for the news! He was sitting in the plastic chair, and he looked the way he looks at you, as if he wants to punch you. Then Villanueva explained, That is a priest, and they killed him. And I thought it was my own craziness when I thought, Oh, and it happened when he was out.”

In the courtroom, Gómez Limón, with a black ponytail and wearing a bulky bulletproof vest, also described the many threats that were made against his family, his children, his brothers. “And then they come and tell my family they’re paying 20,000 quetzales so I won’t say anything. And they come again and they’re offering 100,000 quetzales so I won’t say anything…. Yesterday they came [to my brother] for a third time and they want to know, What’s your brother going to say? Many strategies have they tried, to stop me from telling the truth.”

The well-tailored defense lawyers—mostly of European blood or very lightly mestizo, in contrast to the prosecution lawyers, judges, and witnesses, who tended to be darker, shorter, more mestizo, some with Indian surnames—began a three-hour cross-examination of the witness. Throughout, Gómez Limón seemed oblivious to their condescension and their evident annoyance at being unable to cow the lower-class, dark-skinned witnesses.

But it was one of the defense lawyers, Ramón González,3 who, sensing that the witness was growing weary from riding the dangerous bull of his own desperate fear, and pushing for a dramatic courtroom moment of his own, provoked the cross-examination’s most memorable revelation, when he pressed the witness to describe what happened in prison after he had spoken to the prosecutor:

Gómez Limón: Stay inside [the guards told him]. Inside, all the time I had to stay inside. They had me worried about poison. They brought me my food. I couldn’t even buy a soft drink. They came to see me…. A person from MINUGUA [the UN peacekeepers] came. They put me in this place, a safe place, near the guard house. People said, Why did you get mixed up in this, if Villanueva is a killer?

Defense (shouting): How is it they came three times, offering money? You took an oath! Give me the names! Can you tell me the names of the people who offered the money!

Gómez Limón: …Those people are here, the ones who are offering the money. The first who came was [his jailhouse lawyer] Paco. Then came the lawyer who is right there. [He points to Roberto Echevarría, Captain Lima’s chief defense lawyer.] He’d come right from the Ministry of Defense, they say.

Roberto Echevarría, an especially caustic cross-examiner, was now being accused before the court of having attempted to buy the witness.4

The third key witness, Rubén “El Colocho” (Curly) Chanax Sontay, was a young homeless man who lived in San Sebastián Park, and who had seen the man without a shirt emerge from the garage on the night of the murder. He had made a statement before the trial began that he’d encountered EMP Specialist Obdulio Villanueva, along with another person he knew only as Quesén, by the park in front of the San Sebastián parish house on Sunday morning, April 26, and that Villanueva had warned him to stay away from the park until ten that night, because “someone was going to die.”

The defense had called Chanax as a witness because his pre-trial statements, if unchallenged, would be devastating to the accused. So, under heavy protection, he was returned from exile as a “star witness.” Chanax, a former soldier, used to work as a car washer alongside the park, near EMP headquarters and the military intelligence offices behind the presidential residence and National Palace. EMP agents frequently walked through the park, and sometimes had their cars washed there; the car washers knew many of them by name.

In court, Rubén Chanax Sontay added new details. He testified that, in 1997, Captain Byron Lima’s father, Colonel Lima, had recruited him as an informer for the G-2, or military intelligence. “I needed money, and I accepted. He gave me a phone number. Report everything you see here. I had to call every Saturday. Three months later he says, Now I have a special job for you. I want you to watch Monseñor” (Bishop Gerardi). When he phoned to inform on the bishop, he was simply to say the code words “Operation Bird.”

With that revelation, aspects of Chanax’s story seemed more credible. Why had Villanueva warned him, a vagrant, to stay out of the park because someone was going to die? It now seemed plausible that he had warned him because he knew that Chanax was an informer. A little after nine o’clock that night, Chanax and, later, El Chino Iván Aguilar, another of the vagrants, were in a little neighborhood shop owned by a man known as Don Mike, watching a movie on the small portable television set there. The neighborhood, at that hour, was deserted. Colonel Lima, according to Chanax, came into the shop with three men he didn’t recognize. The men huddled at the counter, drinking beer, talking. In that shop, in order to have a direct line of vision of the San Sebastián Church parish house, all Colonel Lima had to do was go outside into the street and cross to the opposite sidewalk.

The colonel, as a leader of the powerful war veteran officers group, was an obvious suspect. He was particularly threatened by the potential prosecution of human rights crimes after the bishop’s report. “What was the accused doing in that shop?” the judges asked in their verdict. After taking into account Colonel Lima’s connection to the license plates that the taxi driver had noted down, as well as his own belated and unconvincing attempts to manufacture an alibi for his whereabouts that night, the judges decided in the verdict that it was “by all lights logical” to assume that the colonel “had knowledge of what was happening in the San Sebastián parish house.” They concluded that his criminal complicity was “not confined to whatever control he had over what was going on in the vicinity, but rather that his participation began much earlier, when he contracted military informers to monitor Monseñor Gerardi.” Even if he only had knowledge of the murder happening half a block away, the judges wrote, he also had criminally complicit “dominion” over the crime—i.e., the power to prevent it.

While he denied having been at the shop at all, Colonel Lima had no convincing alibi for his whereabouts that night. Nor did the defense lawyers dispute the claim that his unlikely presence at the shop, as witnessed by Chanax, would be incriminating—and in their verdict the judges found that it was. Instead, the defense argued that the shop did not even exist. After Chanax gave his testimony the shop’s sign was removed, as was the clock Chanax had identified on the wall, while the shop’s owner refused to talk.

The night of the murder, a little before ten, Chanax left the shop and started back to the park. When he saw how tranquil everything seemed there, he decided that what Villanueva had told him hadn’t happened, and began to prepare his bedding in front of the garage door where the other bolitos slept. It was then he saw the man without a shirt.

“I knew he worked for the EMP,” Chanax testified, and identified the man as “Hugo.” After an exchange of a few words, the man walked off, leaving the door open. Minutes later a black Grand Cherokee Jeep arrived, and two men dressed in black got out through its rear door: Specialist Obdulio Villanueva, carrying a small video camera, and Captain Byron Lima. According to Chanax, Captain Lima said, “Vos, vos serote, [you little shit], come help us—like that, but with stronger words, I can’t say them here…. He grabs my arm, and pushes me inside. They gave me a pair of gloves, the kind doctors use.” There was a body lying face down on the floor in a pool of blood, although Chanax didn’t realize that it was Bishop Gerardi until they turned the body over. While the men from the EMP arranged the bishop’s body—legs crossed just so, hands crossed under the chin—Chanax, as he’d been told to do, scattered some newspapers around the blood, as if to create an impression that a struggle had taken place. Villanueva carried in a large chunk of concrete, which he set down in a pool of blood. Before the pair drove away Captain Lima told Chanax, “If you talk, you’ll end up just the same as this one.”

The small garage door had been left open. Chanax went to the parish house’s main door and rang the bell several times, but no one answered, until suddenly Padre Mario Orantes appeared at the small garage door, wearing a long, black leather coat. Chanax told him, “Padre, they left the door open,” and before he could say anything else, the priest said, “Gracias Colocho,” and kicked the door shut.

Chanax, claiming he didn’t know what else to do, says he lay down to sleep. As a military intelligence informer, he would have understood he had less to fear by staying there and doing as he’d been told. At midnight Padre Orantes, now dressed in a bathrobe, came out again, and addressed the row of bolitos, “Múcha” (boys), “Did you see who came in, who came out?” Chanax said that, referring to the man without a shirt, he had answered, “The only one was the muchacho who came out a while ago. But [Padre Orantes] didn’t even say anything, he just went back inside.” The priest came out again sometime later, and told the bolitos that Bishop Gerardi had been murdered. He took Chanax aside and said, “Tell them what you know, everything except that I came to the door.” Chanax was then driven away by the police.

4.

The prosecution’s case did not depend on Chanax alone. One other witness, the EMP specialist Jorge Aguilar Martínez, was even more important. Unlike Chanax he didn’t appear at the trial, but his sworn testimony was read into the record. He had been former President Arzú’s personal waiter and worked shifts as a concierge at the EMP’s headquarters behind the presidential residence. Before he left Guate- mala, his life had been in such danger that he’d ended up in a foreign political asylum program with a new identity, forbidden by his host country from having contact with anybody connected to the Bishop Gerardi case.

In 1999, when work on the case seemed stalled, two of the young Intocables, searching for information that may have been overlooked, found a letter from a Guatemala City worker claiming that he knew someone who knew someone who knew something. What followed was like the patient work of ants. It took months for the Intocables to persuade one person to introduce them to another. The chain at last led to Aguilar Martínez’s wife, who managed to convince her husband to speak to the ODHA, in spite of the prohibition.

Aguilar Martínez told them that on the last Sunday of April 1998, he’d been on duty, assigned to work the 6-PM-to-dawn shift at the EMP installation as concierge at the main gate. Sometime between 8:00 and 8:30, a red Trooper SUV, carrying Major Escobar Blas, of the EMP’s Protection Service, Specialist Galiano, and two more unidentified specialists from that same unit “that used to be called the G-2” stopped at the gate on its way out. Major Escobar asked for Captain Dubois, Aguilar Martínez’s superior that night, and reported “sin dieciocho” (no problem), and drove off. It could very well be that Major Escobar was transporting the specialists to San Sebastián Church, which they would somehow enter, and there, inside the parish house garage, await Bishop Gerardi’s arrival an hour and a half later.

Captain Dubois then instructed Aguilar Martínez not to register the comings and goings of vehicles and specialists in the ledger that night, as he normally would have been required to do. He was only to man the telephones in that office, which included a private line for Major Escobar Blas. He was also ordered to tell the rest of those on duty that, from that moment on, they were prohibited from entering the “presidential patio,” as the EMP’s sealed-off section, behind the presidential residence, is called.

Shortly after nine Aguilar Martínez began receiving telephone calls on Major Escobar Blas’s line every three or four minutes, reporting, “sin dieciocho,” “no problem,” and finally one that said, “a bomb in front of the José Gil drugstore,” which, according to the judges’ later interpretation, were “code words whose meanings were understood…by Major Escobar Blas.”

Between 10:20 and 10:30, a black Cherokee Jeep, with polarized windows and without plates, drove into the EMP. “In this vehicle were Captain Lima,” Aguilar Martínez testified, “a young man I knew only as Hugo, and three more people, who were completely dressed in black, wore black caps with visors, and dark glasses.” Later in his testimony Aguilar Martínez described the same tattoo that the taxi driver had also glimpsed on “Hugo”‘s arm: parachute corps wings, around the word Kaibil, the most dreaded Guatemalan army special forces unit during the war.

When he got out of the jeep, “Captain Lima went down the corridor that leads directly to Colonel Rudy Pozuelos’s office.” Colonel Pozuelos was the head of the EMP; in the EMP’s chain of command, only the president was higher. Colonel Pozuelos returned with Captain Lima, got into the black Cherokee with the others, and left. Five minutes later a phone call reported that there was a “dieciocho,” danger, a problem. Captain Dubois rang an alarm, and everybody in the EMP that night, according to Aguilar Martínez, spilled out into the “presidential patio.” Some hours later, at 1:30 on Monday morning, the soldiers milling about outside were told that Bishop Gerardi had been murdered at the church across the street from the Third Street exit of the EMP. Later that morning soldiers were summoned to “a meeting in the patio of the presidential residence,” with Colonel Reyes Palencia, the commander of the Presidential Guard, and a lieutenant colonel from the G-2, and were told that they were “strictly prohibited from talking about or revealing anything that had happened the day before.”

In their closing arguments, the defense sounded desperate. Repeatedly, the other defense lawyers shouted, “Chanax lied!” and accused him of being the murderer, in league with organized crime. The silver-haired Julio Citrón, a victorious champion of the military in trial after trial, based his summation on the argument that you couldn’t convict anyone of being an accomplice in an extrajudicial crime if you didn’t know who had committed the murder, as well as on the ludicrous claim that Colonel Lima couldn’t have been in Don Mike’s little shop because that shop didn’t exist (in the court records the address had been written down incorrectly).5

In their closing arguments, the prosecutors and the ODHA’s lawyers laid out their case. The murder of Bishop Juan Gerardi was a politically motivated crime of state, they said, conceived in retaliation for the REMHI report and as a scheme to obscure its message. It was an elaborately planned execution carried out by an unknown number of Guatemalan military intelligence operatives, and set in motion on the morning of Sunday, April 26, with Specialist Villanueva leaving the Antigua prison, and Captain Byron Lima flying in from an overseas training mission. The lawyers asked for proceso abierto, open criminal investigations, against, among others, some of the likely “intellectual authors” of the crime, EMP Majors Villagrán and Escobar Blas, and the head of the EMP at the time, Colonel Rudy Pozuelos.

The verdict against the military men on trial convicted only three of the no doubt numerous military participants in the crime. They were convicted not as individual “criminals” and “murderers,” but of having “taken part” in a politically motivated act of state-sponsored murder. It was a long-planned operation, an elaborately staged murder and cover-up, involving a great many more military men, freelance operatives from the murky world where organized crime and military intelligence units overlap, and others, perhaps even civilian politicians and corrupt church officials, including Padre Orantes. There were probably stakeouts in the park that night (a couple seen snuggling on a bench in the dark), infiltrators among the vagrants and car washers (Chanax Sontay, for one), and getaway drivers set into motion—by Colonel Lima, perhaps, standing on the sidewalk opposite the shop, staring into the park and parish house garage—to scoop up the “specialists” dressed in black as they fled through the various exits of San Sebastián Church; while the shirtless “Hugo” allowed himself to be seen, quietly igniting rumors that it had been a “crime of passion.” But nobody had planned on an alert and suspicious taxi driver, with a knack for memorizing plate numbers, to drive right into the middle of the operation. And they certainly never planned on the tenacity of the ODHA, and then, just as remarkably, of the young chief prosecutor, Leopoldo Zeissig, who refused to be corrupted or cowed as his predecessors had been, not to mention the trio of similarly stalwart young judges who had presided over the trial.

The convictions opened the way for a more complete investigation of what happened that April night, and after. In his closing statements, Mynor Melgar made clear that the ODHA would not cease from pursuing that case even if it meant eventually bringing charges against officers of higher rank than Colonel Pozuelos—or even former President Arzú himself.

5.

Back in the 1980s, it had been a commonplace among US politicians and reporters to claim, when speaking of Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras, that death squad paramilitaries and the national armies of those countries were not one and the same. Recently, Stephen Kinzer of The New York Times claimed that Bishop Gerardi had been murdered by mysterious “thugs who reject the idea of peace, many of them renegade army and police veterans, [who] still roam at night.” But Bishop Gerardi was not murdered by “renegades.” The Bishop Gerardi trial placed before the judges and the Guatemalan public convincing evidence that Guatemalan military intelligence and the EMP had carried out the crime, a peacetime murder, in the same manner that those units had carried out so many other murders during the decades of war.

In a prison interview with the Guatemalan journalist Claudia Méndez, Colonel Lima himself, referring to another case, sent a message to the Guatemalan military: “I’m just the point of the spear. When they create a precedent, that which they call jurisprudence, then they’re going to go after the rest….” He then listed human rights cases pending against the military, such as the Dos Erres Massacre case (in which 350 peasants, the majority of them women and children, were slaughtered in 1982); and the trial of the officers accused of being the “intellectual authors” of the murder of Myrna Mack, the anthropologist-activist stabbed to death by a since-imprisoned EMP specialist on a downtown street in another faked “crime of passion.” Both cases have been held up in the courts—the Mack case for seven years—through the tactics of defense lawyers and colluding judges. In a country with sturdier legal and police institutions the Gerardi case would not have had to be pursued by a human rights organization. Overturning the verdict in the Gerardi case on appeal would be a demoralizing defeat for all of those who have been trying for decades to end the military’s long impunity in the Guatemalan courts; it would also, of course, end any criminal investigation of other military intelligence officers accused of being “intellectual authors” of the bishop’s murder.

And the verdict could be overturned.6 All it would take is a presiding judge of the old style, a crony of the military. Indeed the judge who will be hearing the appeal has been accused by the ODHA of being such a man. They have sued to have him recused, but lost.

Yet there will be many pressures on the appellate judge. The greatest is that he will have to justify his ruling on the meticulous three-hundred-page verdict to the Guatemalan public and press. But whatever happens, it is a fact that at the Bishop Gerardi murder trial, a powerful case, in the face of extraordinary intimidation, was successfully made in court against Guatemalan military officers, their convictions were won, and the inner workings of a military intelligence operation to commit a political murder were exposed and detailed as never before. That in itself was its triumph.

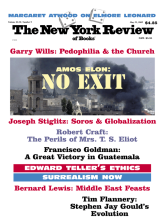

This Issue

May 23, 2002

-

1

Following the grenade attack against Judge Barrios, US Ambassador Prudence Bushnell and other foreign diplomats had held a meeting to support the judges. The “meeting” was portrayed by the defense as interference in the case.

↩ -

2

See my article “Murder Comes for the Bishop,” The New Yorker, March 15, 1999.

↩ -

3

González was the lawyer for Margarita López, the housekeeper at San Sebastián, a fourth defendant who was acquitted at the trial of charges of having withheld evidence.

↩ -

4

Other testimony against Villanueva came out during the trial: for example that Villanueva had been eligible for parole on April 24, two days before the murder, but chose not to leave the prison until four days later.

↩ -

5

The defense, in trying to portray the witnesses as motivated by greed, perhaps was counting on confidentiality agreements with asylum-providing embassies to keep the truth about such witnesses from emerging. The defense’s views have found their way into the press. One example is the article on the Gerardi case which appeared last August in the prominent Mexican and Spanish magazine Letras Libres, which claimed that Aguilar Martínez had “turned up at the ODHA’s door” to peddle his story and, on that pretext, discarded his testimony entirely. The article also ignored the testimony of the still-imprisoned Gómez Limón.

↩ -

6

The appeal is pending as I write.

↩