“Anything processed by memory is fiction.”

—Wright Morris, in a lecture at Princeton, December 2, 1971, as quoted by Paul Fussell in The Great War and Modern Memory. Wright Morris was born in Central City, Nebraska, in 1910.

NEBRASKA

In 1851, Thomas Kerry, from the village of Trieshon in Lincolnshire, England, sailed across the Atlantic to Boston, where two years later he married Frances Reynolds, who had also emigrated from Lincolnshire. The new family pushed west, to Galena, Illinois, and it was in Galena that Thomas Kerry added a second “e” to his name, making it “Kerrey,” perhaps because the earlier spelling had the burden of an Irish connotation in a new world where, on the social ladder, the Irish were just a rung above people of color. The family grew to seven children, and succeeding generations struck out to various other points on the American compass—Manistee, Michigan; Chattanooga; Chicago; Duluth. This was an America on the move, a land where boom was followed by bust, and where, when mothers died either young or in childbirth, as was not uncommon, spinster or widowed relatives were enlisted to help raise the motherless children; refusing the enlistment was not an option. James Kerrey, the father of Robert, was born in 1913; his mother died of toxemia less than three months later, his father of a chill a year after that. A widowed aunt in her mid-fifties with grown children of her own was entrusted with the care of the infant James and of his brother John, older by two years.

According to Kerrey family lore, John Kerrey was a road rat who rode the rails during the Depression, moving from hobo jungles to, finally, the Civilian Conservation Corps. The eligibility requirements for the CCC were simple: the applicant had to be a male American citizen, unemployed, free of venereal disease, and to have “three serviceable teeth, top and bottom.” Both John and James Kerrey served as army officers in the Second World War. John was killed in the Philippines; James did not get overseas until hostilities ended. In 1946, James Kerrey, married and with a growing family (there would be seven children), after many intermediate stops in the Midwest and South, settled for good in Bethany, a suburb of Lincoln, Nebraska, and opened a lumber, coal, and hardware business. James and Elinor Kerrey’s third child, and third son, was J. Robert, called Bob, a Congressional Medal of Honor winner in Vietnam, former Democratic governor of Nebraska, and two-term US senator.

When I Was a Young Man is the first volume of Bob Kerrey’s memoirs. On its smooth, flat surface, it is the story of a thoroughly conventional Midwestern childhood in a thoroughly conventional Midwestern family, with thoroughly conventional Mark Hanna Midwestern Republican politics—limited government and low taxes—and thoroughly conventional Midwestern Protestant beliefs. The family worshiped at the Bethany Christian Church, where Sunday services were preceded by an hour of Bible study, and the young were welcomed into God’s army via a total immersion baptism, as Bob Kerrey was. Kerrey’s book is conventional, however, only in the sense that the literature of the Midwest—Sherwood Anderson’s Winesburg, Ohio, say, or Evan Connell’s Mrs. Bridge and Mr. Bridge, or Wright Morris’s Ceremony in Lone Tree, or Willa Cather’s My Ántonia—seems always to be about emotions camouflaged under a blanket of the ordinary and the quotidian; duty delayed was a promise unkept. It was a world, said Cather’s narrator in My Ántonia, “bridled by caution.”

Kerrey’s tone is Midwestern laconic—uninflected, cool, distant. A generational wall inhibited family communication; in any case communication seemed a modern fad. He feels close to the epic empty landscape of his native state. Of a dusty prairie town in western Nebraska, he writes: “When the grass is high and green it looks like a raft at sea. Driving northwest on a steady wind, you can be tricked into seeing the hills move like rolling waves.” His relationships with women are treated with restraint and wry understatement: “We skated and sailed an iceboat until we were completely frozen and then sat by the fire talking about the possibility of a future together. The talks ended inconclusively.” The implacable control only wobbles when he wanders into the generalities of geopolitical cause and effect. It is a comment on the quality of public discourse that one is obliged to say this is a memoir that did not have a ghost sitting in front of the computer of its putative author.

Although physically slight, Kerrey played center on his high school football team, and beat up a classmate he suspected of trying to sexually molest his retarded older brother; he was nearly killed when the classmate stuck him with a pair of pruning shears that penetrated to within a half-inch of his cardiac membrane. The police were called, he received a restraining order from the authorities, and he never told anyone the reason for what seemed an unprovoked assault. He graduated from the University of Nebraska with a degree in pharmacology; training to be a pharmacist seems now to have been an odd choice, as if his, or his family’s, aspiration level was lit by a low flame. In 1964, he voted for Barry Goldwater, and four years later, shortly before his departure for Vietnam, he voted for Richard Nixon. Kerrey’s service as a naval officer in Vietnam concluded with the action that cost him his right leg and for which he was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor at a White House ceremony presided over by President Nixon.

Advertisement

Over the next dozen years, Kerrey changed his political affiliation to Democrat—his tour in Vietnam was the proximate reason—opened restaurants and health clubs in Lincoln and Omaha that allowed him to accumulate some wealth, married, fathered two children, and then divorced. In 1982, he was elected Democratic governor of Nebraska; the highlight of his governorship (at least in the public memory) was a liaison with a Hollywood actress that was both, improbably, very public and very discreet. Even with a stratospheric approval rating, he declined to run for a second term. He took two years off, then in 1988 ran for and was elected to the US Senate. In 1992, he made a pass at the Democratic nomination for the presidency, running a campaign that can best be described as haphazard and catastrophic, less professional even than Jerry Brown’s.

In the Senate, however, he had established himself as a bright and prickly maverick, not averse to sharp criticism of his own party, its policies, and its leaders, most especially Bill Clinton. In 2000, he chose not to run for a third term to which he was a cinch to be reelected. Instead he moved to New York, became president of the New School University, and remarried. Then, in the spring of 2001, Kerry got shoved back into the public spotlight by claims about a military mission he had commanded in Vietnam. The ensuing uproar confirmed once again that the Vietnam War has permanently insinuated itself into the national imagination, where it resides like a termite, or a virus that periodically becomes virulent.

SEAL

1965: about the spreading conflict in Southeast Asia, Kerrey was ambivalent. “I had neither a deep-seated moral opposition to the war nor a reasoned opposition to fighting the Vietcong and the North Vietnamese,” he writes. “I just preferred to miss this one if possible.” He had asthma, which could have won him the deferment from military service that most college- educated members of his generation avidly sought, either by licit or illicit means. Amiable family doctors produced medical certificates, and a newfound passion for the word of the Lord filled the nation’s divinity schools; the poor and the underprivileged marched to their draft boards.

With an uneasy sense of obligation, Kerrey volunteered for Navy Officer Candidate School, and after he was commissioned an ensign, volunteered again for UDT training on Coronado Island, across the bay from San Diego. UDT meant Underwater Demolition Team, or the planting of explosives on hostile beaches. Each team consisted of one officer and six enlisted men; there was of course a chain of command, but in such a small unit the seven were interdependent, the officer first among equals. Training was fierce; more than a third of the volunteers dropped out. Miscalculation could result in harrowing death, as it did for two men in Kerrey’s class who drowned during an exercise.

At the conclusion of the UDT course, Kerrey was asked by his superiors to sign up for a SEAL platoon, SEAL being the acronym for Sea, Air, and Land—in other words, the Navy’s Green Berets, with flippers, face masks, wet suits, and scuba tanks. The assignment was his to refuse; the Navy’s extortion, however, was that refusal meant assignment as a deck officer to a ship of the fleet, wasting the months of UDT training. Kerrey’s account of advanced SEAL training at Coronado and the Ranger and Airborne training he received at an army base in Georgia is eerie in its relentlessness. For page after page two words recur: “We learned…” Learned to distinguish between differing caliber rifle sounds. Learned the difference between aimed fire and firing for the effect of noise. Learned how to call in artillery and how not to aim an assault rifle high at night. Learned how to secure and inspect small buildings. Learned how to radio for gunships. Learned why an injured or wounded man could jeopardize the lives of an entire seven-man SEAL squad because it took two men to carry one out. This incantation of “We learned” provided, Kerrey acknowledges, a baffle between what was learned and why it was learned: to kill people automatically and efficiently, without thought, fear, or lenience.

Advertisement

The SEALs were the Navy’s public relations dream team. When Kerrey, now a lieutenant (j.g.), arrived in Vietnam early in 1969, his unit was under the administrative control of an in-country Navy command, but under the operational jurisdiction of SEAL Headquarters in Coronado. This meant that local commanders could not order the SEALs on exercises that might make them appear peripheral, or in a support role. The result was that Kerrey’s SEAL Platoon 1 was essentially a search-and-destroy vigilante unit whose charter was, he writes, “to set ambushes, abduct enemy personnel, and gather intelligence”; ambush is a polite way to say “kill.” The unit was free to wander the Vietnamese coast searching for a war to fight, an enemy to engage. Each fast boat squad was armed with a mortar, a heavy machine gun, explosives, grenades, grenade launchers, automatic weapons, and knives. There was no reliable intelligence beyond that of rumor or what came from Vietnamese military or political officials currying favor with their American patrons; information was currency, a hedge against the future, available to whoever wanted it most, whatever the side. And the question of who was the enemy was never satisfactorily resolved. The Vietnamese, Kerrey says,

tended to give their sympathy to whomever they feared the most. Either way they could lose. They risked having us destroy their villages if they cooperated with the Vietcong and having the Vietcong destroy their villages if they cooperated with us.

Kerrey’s squad consisted of six enlisted men and a Vietnamese frogman who was the team’s interpreter. Two of the men—Gerhard Klann and Mike Ambrose—had seen combat in previous tours. (Each SEAL, it should be noted, only served six months in Vietnam, as opposed to the 365 days ordinary servicemen spent before rotation home. High-profile SEAL billets were much in demand, and the shorter tours allowed more career officers and men to get their tickets punched.) At home the war had degenerated into a social and political disaster. There were peace marches and flag burnings; drugs and racial tension infected the body politic. It was little different in Vietnam. A military force of half a million men was so bloated with support, logistical, and public relations lard that only 12 percent of those in uniform were actually in harm’s way, under fire. On a normal day at Cam Ranh Bay, Kerrey writes, “the only obstacles to our safe passage were Americans moving in the other direction, headed for the beach carrying food, drink, chairs, and surfboards.” Officers and men kept calendars, scratching off each day remaining before the plane out. The “short-timers”‘ abracadabra magic word was FIGMO—“Fuck It, Got My Orders.”

For nights on end, Kerrey’s squad set up ambushes in various Mekong Delta hamlets, but no one came; their intelligence was either faulty or had been traded or contaminated. Toward the end of February, there were reports of a high-level Vietcong meeting in a village called Thanh Phong. The meeting seemed to offer a training-course SEAL operation: take a fast boat in under cover of darkness, shoot up the VC, grab a prisoner, head back to the fast boat, and go home. In turf-conscious Navy fashion, however, the area commander was not enthusiastic about a bunch of freelance cowboys operating outside his control, and would not promise air support. Nor was Ambrose, one of Kerrey’s two experienced men, easy about going to Thanh Phong. The team’s Vietnamese interpreter was not available, which Ambrose thought increased the risk factor on a night mission where there would be a lot of shouting, no one understanding, and gunfire ultimately the language of choice; the absence of air support only added to Ambrose’s disquiet.

Thanh Phong, Kerrey writes, was located in what the American and Vietnamese military called a Free Fire Zone, a euphemism for “shoot at anything.” The Vietnamese district chief said the entire village was Vietcong; he also said there were no civilians present, which meant that anyone the team ran into was likely to be VC or a supporter. This information was parsed in the military speak that corrupted the entire Vietnam experience: orders were both direct and evasive, specific and slippery with innuendo, simple and rich with shadowy interpretations. To allay his own reservations, Kerrey made a low-level aerial daytime reconnaissance of the village, identifying the houses where the meeting was supposed to take place and where guard stakeouts might be. “That surveillance flight,” he writes, “confirmed that there were no women or children in the area.” Although Kerrey does not say so, what the flight might also have done was to alert any Vietcong that a mission was coming.

From the get-go, the engagement at Thanh Phong was a murderous folly. If there was a meeting, it had been abandoned. There were women and children present. Using their knives, Gerhard Klann, the squad’s other experienced man, and several squad members killed the inhabitants of the house that was supposed to be the sentry post; the silence of the knife made it the weapon of choice in dispatching sentinels who could sound an alarm. No order needed to be given; it was tactical operating procedure. A babble of voices erupted from other houses in the village. There were no men in the houses, meaning the action had been compromised. A shot was either fired at the SEAL team, or not: allowing for the element of fear that is a component of any military action, especially one at night in enemy territory, perhaps the shot, or what was perceived as hostile intent, was only imagined. The SEALs opened up with everything they had. “I saw women and children in front of us being hit and cut to pieces,” Kerrey writes. “I heard their cries and other voices in the darkness as we made our retreat…. The possibility of being pursued or of being caught in an ambush ourselves seemed very real to me.”

Kerrey had been in Vietnam five weeks. The mission to Thanh Phong was his first firefight. “I felt a sickness in my heart for what we had done,” Kerrey writes. “I had become someone I did not recognize.” Thirty-two years later, from the minefield of repressed memory, that night in Thanh Phong became a controversial national event.

NHA TRANG

What was striking about SEAL operations was the extraordinary independence each unit enjoyed; going or not going on a mission was generally a judgment call by the SEAL officer commanding, one usually quite junior to local commanders who were half-colonels or higher. After Thanh Phong, Kerrey’s team left the Delta and returned to Cam Ranh Bay, where a Vietcong deserter reported that a VC sapper unit was killing civilians at Nha Trang, north of Cam Ranh. The sappers were operating from a small island in Nha Trang harbor: the SEAL mission was to shut the VC sappers down. “Some of the senior officers argued unsuccessfully that we should not try to take prisoners,” Kerrey writes. “We should just kill them as they slept and leave.” Kerrey’s plan was less unequivocal: his squad would land, hide its rubber boats, climb a cliff, wake the sleeping sappers with force, bind and gag them with tape, and call for a chopper to remove them to Nha Trang.

As happens in military operations, what could go wrong did go wrong, and worse. Surprise was lost, and in the ensuing firefight an explosion ripped open Kerrey’s right leg, detaching his foot from his calf. He wrapped a tourniquet around his knee and injected morphine into his thigh. Gerhard Klann held him in his arms, and gave him an unfiltered cigarette to smoke until the medevac chopper could evacuate him. The helicopter pilot would not land on an island that was not secure; he lowered a sling and Kerrey’s men wrapped him inside it. On the way up to the chopper, a finger on his left hand caught on a tree limb and shattered. From a hospital in Cam Ranh Bay, two letters were sent to his parents, ostensibly from Kerrey, but not in his handwriting; the letters downplayed his injuries, glowed about the war stories he would get to tell, and told of his affection for his platoon. “Both letters were full of lies,” he says. “My fifty-plus days in Vietnam seemed to me to be at best a waste of time.”

AMPUTATION

The next year was a chronicle of horror and, in its pitilessly precise and unsqueamish telling, the most remarkable section of this ineffably sad, tormented, and wonderful book. It is as if Kerrey regards sentiment as an affront, a betrayal of the reader, or himself. When he woke in a hospital in Japan after a flight he did not remember taking, an amputee patient in another bed was crying. “I was looking at a cross section of his upper thigh,” Kerrey writes. “It looked like a piece of meat in a butcher shop. The femur had been neatly sawed, and to me it looked like the white eye of the Cyclops in a monster’s face.” He fell asleep and when he awoke again, the other bed was neatly made up as if it had not been occupied; a nurse told him the patient had died during the night of a pulmonary embolism. Doctors told Kerrey it was unlikely his leg could be saved, and that he would be flown to a military hospital of his choice in the States. He picked one in Philadelphia, “because it was the farthest from home and the people I knew.”

On the flight across the Pacific, the patient in the bunk above dripped blood down on Kerrey’s blanket; the dripping stopped when the man died. A morphine IV kept Kerrey’s pain at bay all the way to Philadelphia. In the elevator at the hospital, he writes,

I was startled to see a man in a wheelchair. He did not make a sound. He leaned toward me with the weight of his body resting on the elbow of his remaining arm. His right arm was missing above the elbow, as were both of his legs. I looked directly into his face except there was no face. In the place of eyes, nose, and lips was a sunken cavity smooth and free of scars.

The hospital was a refuge in a way that Lincoln never was, nor the Navy. “Among my fellow patients I felt safe,” he writes. “I did not have to hide my deformities because we were all disfigured. We were a brotherhood of cripples, bound together by our deformities and the indignities we endured.” The brotherhood empathized with the foulest injuries. Kerrey’s hospital roommate had been so fearfully burned in a helicopter crash that his dressings had to be changed in a whirlpool so they would not peel away his skin grafts. “The pain…caused him to thrash uncontrollably in the water, which darkened with his blood as though he were being attacked by piranhas.”

Triumphs were no less valued because they were small; Kerrey’s ability finally to pee standing up was a moment to celebrate. Saving his leg was now out of the question; gangrene had set in under his cast. “It no longer resembled a leg,” he writes.

Bones stuck out at disorderly angles from flesh spread wide and flat across the bloodstained sheet. My ankle and heel were completely gone. The blackened toes were attached to my only remaining metacarpals, which were no longer attached to anything at all.

Don’t take more than you have to, he instructed the doctor who performed the amputation just before he went under. Rehabilitation was painful and inexact. “Broken skin does not heal well inside the dark, tight, hot, and moist environment of a prosthesis socket,” he notes. Periodically he would have surgical revisions to reduce the scar tissue around his stump; the last revision occurred nine years after he left the Navy.

In the summer of 1969, Kerrey learned that his role in the firefight at Nha Trang had earned him a recommendation for the Congressional Medal of Honor. His SEAL team had put him in for a Silver Star, but his nomination had been upgraded. Kerrey was ambivalent; other than being wounded he did not think he had been particularly heroic at Nha Trang. Given the extent of horse trading among military brass for medals, he believed the best solution was to eliminate all except the Purple Heart, where the recipient’s wounds were proof that it was earned. In November 1969, Kerrey was discharged; it was the weekend of the Vietnam Moratorium, and also the weekend that the first reports of the My Lai massacre were published. Some months later, Kerrey flew to the White House to accept his Medal of Honor alongside twelve other medal winners. Kerrey tried to charm Julie Nixon Eisenhower, who was President Nixon’s hostess for the presentation: “She showed no interest in my charm.”

AFTERMATH

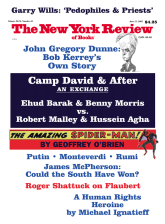

On April 29, 2001, Kerrey’s photograph appeared on the cover of The New York Times Magazine over the headline “One Awful Night in Thanh Phong.” Four years earlier the author of the piece, Gregory L. Vistica, had stumbled on a source, a former SEAL officer, who directed him to a retired SEAL with bad memories about a failed mission and the murder of women and children. The SEAL was Gerhard Klann, retired after twenty years in the Navy, living outside Pittsburgh, and occasionally troubled by overindulgence with alcohol. Vistica, at that time a Newsweek reporter, contacted him, and during a series of interviews, Klan began to unburden himself about the mission to Thanh Phong. In the guard post, Klann said, were an old man, a woman about his age, and three children. Kerrey, according to Klann, held the old man down with his knee while Klann slit his throat. The SEALs then rounded up the women and children in the other houses of the village, and shot a dozen or more at point-blank range.

Vistica left Newsweek in 2000, kept the story, and sold the idea both to the Times Magazine and to CBS’s 60 Minutes franchise. In Vietnam a 60 Minutes II camera team shooting footage for the show in Thanh Phong discovered an elderly Vietnamese woman who claimed to have witnessed the killings. Her name was Pham Tri Lanh, she had been a Vietcong supporter in 1969, and she corroborated Klann’s account. Under close scrutiny by reporters from Time, however, Pham Tri Lanh’s testimony became less insistent, more malleable. She admitted that she had not actually seen the massacre; she had heard the screams of the dying, she now said, and had seen their bodies lined up.

The story in the Times Magazine erupted into a firestorm that nearly engulfed Kerrey, and his interview two days later on 60 Minutes II only poured gasoline onto the flames. The collaboration of these two media icons lent an instantaneous gravity to assertions that were presented as charges but were, in fact, never precisely nailed down. I have never been entirely comfortable with the methods of 60 Minutes, and even less so with its JV version, 60 Minutes II. Twenty-five years ago in The New Yorker, Michael Arlen examined the 60 Minutes phenomenon as entertainment in the form of dramatic confrontation. The process of gathering the story was part of the story, radio’s Front Page Farrell in the television age. What sustained the show, Mr. Arlen wrote, was “the thrill of the chase…the drama of pursuit” and “interview subjects who can be made to serve, willingly or unwillingly, as the quarry.” A quarter of a century later, the formula has not changed. There is “B-roll” (narrative filler film) of people striding purposefully into (or out of) buildings or getting into (or out of) their cars; in this instance, it was Gregory Vistica staring at his computer. The bones of the story are fitted to the star personality of the presenter, who in fact has done little reporting; the heavy lifting is mainly done by reporters and producers whose names are buried in the credits.

Kerrey’s interrogator on 60 Minutes II was Dan Rather. Rather has always seemed one of the more dubious of the network news stars. He affects a military bearing and courtly Southern manners (he is from Wharton, Texas, fifty miles southwest of Houston), and occasionally slips into down-home country metaphors of the “that dog don’t hunt” variety. He has published half a dozen books, and he has employed a writer to help compose most of them; it is not exactly unseemly for a journalist (whose business is after all words) to use a ghost, but it does seem curious. His interviewing style is that of a crusading DA running for reelection in Wharton County. Hard, short, rapid-fire questions that demand yes or no answers, punctuated with the pregnant pause. It is a tawdry star- chamber technique designed less to elicit facts than to imply malfeasance, and it was in full play when he faced Kerrey:

Rather: You have no memory of the inhabitants of the main part of the village being lined up…

Kerrey: No.

Rather: And shot at point-blank range…

Kerrey: No.

Rather: ….repeatedly with automatic weapons…

Kerrey: No.

Rather: …and forgive the reference—with literally blood and guts splattering all over everybody.

Kerrey: No.

Rather: You have no memory of that?

The other five members of the squad contradicted Klann’s memories. What is most interesting about the different recollections of the two sides was how unjudgmental and unpunitive, at least publicly, they were toward each other. If Kerrey thought he could keep in front of the story, however, he was quickly disillusioned. To the unbelievers, the testimony of Kerrey’s five other subordinates was seen as discounted or even counterfeit tender. “Kerrey’s Massacre” was the headline in the New York Daily News, and the rhetoric was only slightly less heated in other papers across the country. In the Letters columns and on the Op-Ed pages, it was as if the Vietnam War was being replayed, from the same domestic bunkers and hooches that had been dug thirty years earlier; on Antiwar.com, the headline was “Is Bob Kerrey a War Criminal?” No one’s mind seemed to have changed; the young, many of them pre-schoolers or adolescents in 1969, were as rigid as their elders. Four US senators—Republicans John McCain and Chuck Hagel, Democrats Max Cleland and John Kerrey, all decorated Vietnam combat veterans—rose to defend their former colleague and invoked the fog of war. In The Boston Globe, Daniel Jonah Goldhagen and Samantha Power hinted at war crimes and the necessity of an investigation: “How can anyone in good conscience countenance a cover-up of how and why [the villagers at Thanh Phong] were killed?”

The more-rigorous-than-thou position was that Kerrey, because of the high regard in which he was held by the well-connected, was receiving a dispensation from close official investigation. “Every aspect of this rush to avoid judgment is wrong,” Michael Kelly wrote in The Washington Post; the rush to judgment seemed to trouble him somewhat less. In print, veterans picked at the scabs of their memories and found, unhealed, choices and split-second decisions that saved or did not save lives. Perhaps the most nuanced response came from my friend William Broyles, a Marine lieutenant in Vietnam, later editor of Newsweek and a screenwriter who was nominated for an Academy Award. “They called from the NY Times for me to do an op ed,” he e-mailed after we discussed the Kerry incident. He found he had nothing he wanted to say. “I looked inside and found only a long ocean view dimming into mist. There was just nothing there. No outrage, no pity, no nothing. And THAT was what worried me.” Now also teaching at the University of Texas in Austin, he had tried to explain Thanh Phong to his honors English class, and wrote: “I might as well have been talking about the Punic Wars.”

In When I Was a Young Man, Kerrey adamantly refuses to address the furor raised by the Times Magazine and 60 Minutes II. He knows that when the book is published Memorial Day weekend, public forums will again chew over the issue, the arguments will be repeated, he will be back in the dock. A killing mission became or did not become a firefight, the firefight became a slaughter, the slaughter became a story, the story became narrative, as do all stories when they are processed by memory, which is what Wright Morris understood. The narrative had competing memories and competing versions; the outlets where the narrative was constructed and deconstructed had agendas of their own.

In newspaper accounts Kerrey made it clear that he felt he was burned in the Rather interview. He is a politician, however, used to the rough and tumble of the campaign trail as well as to the mud-wrestling of confrontational TV, and he should have known what he was getting into. There was a show and he was not the star of the show; he was, as Michael Arlen wrote twenty-five years ago, the quarry. Gregory Vistica’s “One Awful Night in Thanh Phong” was a runner-up in the national reporting category in this year’s Pulitzer Prizes, and he has a $250,000 contract to write a book about the incident, The Education of Lieutenant Kerrey. Dan Rather recently went to Israel to cover that conflict, and he told Larry King in a pickup from the battle zone: “Danger is my business.”

In the end we were left to believe that those who were not at Thanh Phong would have practiced perfect fire discipline if they had been. To which perhaps the only possible answer is what Jake Barnes said to Brett Ashley in the last line of The Sun Also Rises: “Isn’t it pretty to think so.”

This Issue

June 13, 2002