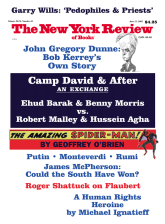

1. An Interview with Ehud Barak

The following interview with Ehud Barak took place in Tel Aviv during late March and early April. I have supplied explanatory references in brackets with Mr. Barak’s approval.

The call from Bill Clinton came hours after the publication in The New York Times of Deborah Sontag’s “revisionist” article (“Quest for Middle East Peace: How and Why It Failed,” July 26, 2001) on the Israeli–Palestinian peace process. Ehud Barak, Israel’s former prime minister, on vacation, was swimming in a cove in Sardinia. Clinton said (according to Barak):

What the hell is this? Why is she turning the mistakes we [i.e., the US and Israel] made into the essence? The true story of Camp David was that for the first time in the history of the conflict the American president put on the table a proposal, based on UN Security Council resolutions 242 and 338, very close to the Palestinian demands, and Arafat refused even to accept it as a basis for negotiations, walked out of the room, and deliberately turned to terrorism. That’s the real story—all the rest is gossip.

Clinton was speaking of the two-week-long July 2000 Camp David conference that he had organized and mediated and its failure, and the eruption at the end of September of the Palestinian intifada, or campaign of anti-Israeli violence, which has continued ever since and which currently plagues the Middle East, with no end in sight. Midway in the conference, apparently on July 18, Clinton had “slowly”—to avoid misunderstanding—read out to Arafat a document, endorsed in advance by Barak, outlining the main points of a future settlement. The proposals included the establishment of a demilitarized Palestinian state on some 92 percent of the West Bank and 100 percent of the Gaza Strip, with some territorial compensation for the Palestinians from pre-1967 Israeli territory; the dismantling of most of the settlements and the concentration of the bulk of the settlers inside the 8 percent of the West Bank to be annexed by Israel; the establishment of the Palestinian capital in East Jerusalem, in which some Arab neighborhoods would become sovereign Palestinian territory and others would enjoy “functional autonomy”; Palestinian sovereignty over half the Old City of Jerusalem (the Muslim and Christian quarters) and “custodianship,” though not sovereignty, over the Temple Mount; a return of refugees to the prospective Palestinian state though with no “right of return” to Israel proper; and the organization by the international community of a massive aid program to facilitate the refugees’ rehabilitation.

Arafat said “No.” Clinton, enraged, banged on the table and said: “You are leading your people and the region to a catastrophe.” A formal Palestinian rejection of the proposals reached the Americans the next day. The summit sputtered on for a few days more but to all intents and purposes it was over.

Barak today portrays Arafat’s behavior at Camp David as a “performance” geared to exacting from the Israelis as many concessions as possible without ever seriously intending to reach a peace settlement or sign an “end to the conflict.” “He did not negotiate in good faith, indeed, he did not negotiate at all. He just kept saying ‘no’ to every offer, never making any counterproposals of his own,” he says. Barak continuously shifts between charging Arafat with “lacking the character or will” to make a historic compromise (as did the late Egyptian President Anwar Sadat in 1977–1979, when he made peace with Israel) and accusing him of secretly planning Israel’s demise while he strings along a succession of Israeli and Western leaders and, on the way, hoodwinks “naive journalists”—in Barak’s phrase—like Sontag and officials such as former US National Security Council expert Robert Malley (who, with Hussein Agha, published another “revisionist” article on Camp David, “Camp David: The Tragedy of Errors”*). According to Barak:

What they [Arafat and his colleagues] want is a Palestinian state in all of Palestine. What we see as self-evident, [the need for] two states for two peoples, they reject. Israel is too strong at the moment to defeat, so they formally recognize it. But their game plan is to establish a Palestinian state while always leaving an opening for further “legitimate” demands down the road. For now, they are willing to agree to a temporary truce à la Hudnat Hudaybiyah [a temporary truce that the Prophet Muhammad concluded with the leaders of Mecca during 628–629, which he subsequently unilaterally violated]. They will exploit the tolerance and democracy of Israel first to turn it into “a state for all its citizens,” as demanded by the extreme nationalist wing of Israel’s Arabs and extremist left-wing Jewish Israelis. Then they will push for a binational state and then, demography and attrition will lead to a state with a Muslim majority and a Jewish minority. This would not necessarily involve kicking out all the Jews. But it would mean the destruction of Israel as a Jewish state. This, I believe, is their vision. They may not talk about it often, openly, but this is their vision. Arafat sees himself as a reborn Saladin—the Kurdish Muslim general who defeated the Crusaders in the twelfth century—and Israel as just another, ephemeral Crusader state.

Barak believes that Arafat sees the Palestinian refugees of 1948 and their descendants, numbering close to four million, as the main demographic-political tool for subverting the Jewish state.

Advertisement

Arafat, says Barak, believes that Israel “has no right to exist, and he seeks its demise.” Barak buttresses this by arguing that Arafat “does not recognize the existence of a Jewish people or nation, only a Jewish religion, because it is mentioned in the Koran and because he remembers seeing, as a kid, Jews praying at the Wailing Wall.” This, Barak believes, underlay Arafat’s insistence at Camp David (and since) that the Palestinians have sole sovereignty over the Temple Mount compound (Haram al-Sharif—the noble sanctuary) in the southeastern corner of Jerusalem’s Old City. Arafat denies that any Jewish temple has ever stood there—and this is a microcosm of his denial of the Jews’ historical connection and claim to the Land of Israel/Palestine. Hence, in December 2000, Arafat refused to accept even the vague formulation proposed by Clinton positing Israeli sovereignty over the earth beneath the Temple Mount’s surface area.

Barak recalls Clinton telling him that during the Camp David talks he had attended Sunday services and the minister had preached a sermon mentioning Solomon, the king who built the First Temple. Later that evening, he had met Arafat and spoke of the sermon. Arafat had said: “There is nothing there [i.e., no trace of a temple on the Temple Mount].” Clinton responded that “not only the Jews but I, too, believe that under the surface there are remains of Solomon’s temple.” (At this point one of Clinton’s [Jewish] aides whispered to the President that he should tell Arafat that this is his personal opinion, not an official American position.)

Repeatedly during our prolonged interview, conducted in his office in a Tel Aviv skyscraper, Barak shook his head—in bewilderment and sadness—at what he regards as Palestinian, and especially Arafat’s, mendacity:

They are products of a culture in which to tell a lie…creates no dissonance. They don’t suffer from the problem of telling lies that exists in Judeo-Christian culture. Truth is seen as an irrelevant category. There is only that which serves your purpose and that which doesn’t. They see themselves as emissaries of a national movement for whom everything is permissible. There is no such thing as “the truth.”

Speaking of Arab society, Barak recalls: “The deputy director of the US Federal Bureau of Investigation once told me that there are societies in which lie detector tests don’t work, societies in which lies do not create cognitive dissonance [on which the tests are based].” Barak gives an example: back in October 2000, shortly after the start of the current Intifada, he met with then Secretary of State Madeleine Albright and Arafat in the residence of the US ambassador in Paris. Albright was trying to broker a cease-fire. Arafat had agreed to call a number of his police commanders in the West Bank and Gaza, including Tawfik Tirawi, to implement a truce. Barak said:

I interjected: “But these are not the people organizing the violence. If you are serious [in seeking a cease-fire], then call Marwan Bargouti and Hussein al-Sheikh” [the West Bank heads of the Fatah, Arafat’s own political party, who were orchestrating the violence. Bargouti has since been arrested by Israeli troops and is currently awaiting trial for launching dozens of terrorist attacks].

Arafat looked at me, with an expression of blank innocence, as if I had mentioned the names of two polar bears, and said: “Who? Who?” So I repeated the names, this time with a pronounced, clear Arabic inflection—“Mar-wan Bar-gou-ti” and “Hsein a Sheikh”—and Arafat again said, “Who? Who?” At this, some of his aides couldn’t stop themselves and burst out laughing. And Arafat, forced to drop the pretense, agreed to call them later. [Of course, nothing happened and the shooting continued.]

But Barak is far from dismissive of Arafat, who appears to many Israelis to be a sick, slightly doddering buffoon and, at the same time, sly and murderous. Barak sees him as “a great actor, very sharp, very elusive, slippery.” He cautions that Arafat “uses his broken English” to excellent effect.

Barak was elected prime minister, following three years of Benjamin Netanyahu’s premiership, in May 1999 and took office in July. He immediately embarked on his multipronged peace effort—vis-à-vis Syria, Lebanon, and the Palestinians—feeling that Israel and the Middle East were headed for “an iceberg and a certain crash and that it was the leaders’ moral and political responsibility to try to avoid a catastrophe.” He understood that the year and a half left of Clinton’s presidency afforded a small window of opportunity inside a larger, but also limited, regional window of opportunity. That window was opened by the collapse of the Soviet Empire, which had since the 1950s supported the Arabs against Israel, and the defeat of Iraq in Kuwait in 1991, and would close when and if Iran and/or Iraq obtained nuclear weapons and when and if Islamic fundamentalist movements took over states bordering Israel.

Advertisement

Barak said he wanted to complete what Rabin had begun with the Oslo agreement, which inaugurated mutual Israeli–Palestinian recognition and partial Israeli withdrawals from the West Bank and Gaza Strip back in 1993. A formal peace agreement, he felt, would not necessarily “end the conflict, that will take education over generations, but there is a tremendous value to an [official] framework of peace that places pacific handcuffs on these societies.” Formal peace treaties, backed by the international community, will have “a dynamic of their own, reducing the possibility of an existential conflict. But without such movement toward formal peace, we are headed for the iceberg.” He seems to mean something far worse than the current low-level Israeli–Palestinian conflagration.

Barak says that, before July 2000, IDF intelligence gave the Camp David talks less than a 50 percent chance of success. The intelligence chiefs were doubtful that Arafat “would take the decisions necessary to reach a peace agreement.” His own feeling at the time was that he “hoped Arafat would rise to the occasion and display something of greatness, like Sadat and Hussein, at the moment of truth. They did not wait for a consensus [among their people], they decided to lead. I told Clinton on the first day [of the summit] that I didn’t know whether Arafat had come to make a deal or just to extract as many political concessions as possible before he, Clinton, left office.”

Barak dismisses the charges leveled by the Camp David “revisionists” as Palestinian propaganda. The visit to the Temple Mount by then Likud leader Ariel Sharon in September 2000 was not what caused the intifada, he says.

Sharon’s visit, which was coordinated with [Palestinian Authority West Bank security chief] Jibril Rajoub, was directed against me, not the Palestinians, to show that the Likud cared more about Jerusalem than I did. We know, from hard intelligence, that Arafat [after Camp David] intended to unleash a violent confrontation, terrorism. [Sharon’s visit and the riots that followed] fell into his hands like an excellent excuse, a pretext.

As agreed, Sharon had made no statement and had refrained from entering the Islamic shrines in the compound in the course of the visit. But rioting broke out nonetheless. The intifada, says Barak, “was preplanned, pre-prepared. I don’t mean that Arafat knew that on a certain day in September [it would be unleashed]…. It wasn’t accurate, like computer engineering. But it was definitely on the level of planning, of a grand plan.”

Nor does Barak believe that the IDF’s precipitate withdrawal from the Security Zone in Southern Lebanon, in May 2000, set off the intifada. “When I took office [in July 1999] I promised to pull out within a year. And that is what I did.” Without doubt, the Palestinians drew inspiration and heart from the Hezbollah’s successful guerrilla campaign during 1985–2000, which in the end drove out the IDF, as well as from the spectacle of the sometime slapdash, chaotic pullout at the end of May; they said as much during the first months of the intifada. “But had we not withdrawn when we did, the situation would have been much worse,” Barak argues:

We would have faced a simultaneous struggle on two fronts, in Palestine and in southern Lebanon, and the Hezbollah would have enjoyed international legitimacy in their struggle against a foreign occupier.

The lack of international legitimacy, Barak stresses, following the Israeli pullback to the international frontier, is what has curtailed the Hezbollah’s attacks against Israel during the past weeks. “Had we still been in Leb-anon we would have had to mobilize 100,000, not 30,000, reserve soldiers [in April, during ‘Operation Defensive Wall’],” he adds. But he is aware that the sporadic Hezbollah attacks might yet escalate into a full-scale Israeli– Lebanese–Syrian confrontation, something the pullback had been designed—and so touted—to avoid.

As to the charge raised by the Palestinians, and, in their wake, by Deborah Sontag, and Malley and Agha, that the Palestinians had been dragooned into coming to Camp David “unprepared” and prematurely, Barak is dismissive to the point of contempt. He observes that the Palestinians had had eight years, since 1993, to prepare their positions and fall-back positions, demands and red lines, and a full year since he had been elected to office and made clear his intention to go for a final settlement. By 2002, he said, they were eager to establish a state,

which is what I and Clinton proposed and offered. And before the summit, there were months of discussions and contacts, in Stockholm, Israel, the Gaza Strip. Would they really have been more “prepared” had the summit been deferred to August, as Arafat later said he had wanted?

One senses that Barak feels on less firm ground when he responds to the “revisionist” charge that it was the continued Israeli settlement in the Occupied Territories, during the year before Camp David and under his premiership, that had so stirred Palestinian passions as to make the intifada inevitable:

Look, during my premiership we established no new settlements and, in fact, dismantled many illegal, unauthorized ones. Immediately after I took office I promised Arafat: No new settlements—but I also told him that we would continue to honor the previous government’s commitments, and contracts in the pipeline, concerning the expansion of existing settlements. The courts would force us to honor existing contracts, I said. But I also offered a substantive argument. I want to reach peace during the next sixteen months. What was now being built would either remain within territory that you, the Palestinians, agree should remain ours—and therefore it shouldn’t matter to you—or would be in territory that would soon come under Palestinian sovereignty, and therefore would add to the housing available for returning refugees. So you can’t lose.

But Barak concedes that while this sounded logical, there was a psychological dimension here that could not be neutralized by argument: the Palestinians simply saw, on a daily basis, that more and more of “their” land was being plundered and becoming “Israeli.” And he agrees that he allowed the expansion of existing settlements in part to mollify the Israeli right, which he needed quiescent as he pushed forward toward peace and, ultimately, a withdrawal from the territories.

Regarding the core of the Israeli-American proposals, the “revisionists” have charged that Israel offered the Palestinians not a continuous state but a collection of “bantustans” or “cantons.” “This is one of the most embarrassing lies to have emerged from Camp David,” says Barak.

I ask myself why is he [Arafat] lying. To put it simply, any proposal that offers 92 percent of the West Bank cannot, almost by definition, break up the territory into noncontiguous cantons. The West Bank and the Gaza Strip are separate, but that cannot be helped [in a peace agreement, they would be joined by a bridge].

But in the West Bank, Barak says, the Palestinians were promised a continuous piece of sovereign territory except for a razor-thin Israeli wedge running from Jerusalem through from Maale Adumim to the Jordan River. Here, Palestinian territorial continuity would have been assured by a tunnel or bridge:

The Palestinians said that I [and Clinton] presented our proposals as a diktat, take it or leave it. This is a lie. Everything proposed was open to continued negotiations. They could have raised counter-proposals. But they never did.

Barak explains Arafat’s “lie” about “bantustans” as stemming from his fear that “when reasonable Palestinian citizens would come to know the real content of Clinton’s proposal and map, showing what 92 percent of the West Bank means, they would have said: ‘Mr. Chairman, why didn’t you take it?'”

In one other important way the “revisionist” articles are misleading: they focused on Camp David (July 2000) while almost completely ignoring the follow-up (and more generous) Clinton proposals (endorsed by Israel) of December 2000 and the Palestinian– Israeli talks at Taba in January 2001. The “revisionists,” Barak implies, completely ignored the shift—under the prodding of the intifada—in the Israeli (and American) positions between July and the end of 2000. By December and January, Israel had agreed to Washington’s proposal that it withdraw from about 95 percent of the West Bank with substantial territorial compensation for the Palestinians from Israel proper, and that the Arab neighborhoods of Jerusalem would become sovereign Palestinian territory. The Israelis also agreed to an international force at least temporarily controlling the Jordan River line between the West Bank and the Kingdom of Jordan instead of the IDF. (But on the refugee issue, which Barak sees as “existential,” Israel had continued to stand firm: “We cannot allow even one refugee back on the basis of the ‘right of return,'” says Barak. “And we cannot accept historical responsibility for the creation of the problem.”)

Had the Palestinians, even at that late date, agreed, there would have been a peace settlement. But Arafat dragged his feet for a fortnight and then responded to the Clinton proposals with a “Yes, but…” that, with its hundreds of objections, reservations, and qualifications, was tantamount to a resounding “No.” Palestinian officials maintain to this day that Arafat said “Yes” to the Clinton proposals of December 23. But Dennis Ross, Clinton’s special envoy to the Middle East, in a recent interview (on Fox News, April 21, 2002), who was present at the Arafat–Clinton White House meeting on January 2, says that Arafat rejected “every single one of the ideas” presented by Clinton, even Israeli sovereignty over the Wailing Wall in Jerusalem’s Old City. And the “Palestinians would have [had] in the West Bank an area that was contiguous. Those who say there were cantons, [that is] completely untrue.” At Taba, the Palestinians seemed to soften a little—for the first time they even produced a map seemingly conceding 2 percent of the West Bank. But on the refugees they, too, stuck to their guns, insisting on Israeli acceptance of “the right of return” and on Jerusalem, that they have sole sovereignty over the Temple Mount.

Several “revisionists” also took Barak to task for his “Syria first” strategy: soon after assuming office, he tried to make peace with Syria and only later, after Damascus turned him down, did he turn to the Palestinians. This had severely taxed the Palestinians’ goodwill and patience; they felt they were being sidelined. Barak concedes the point, but explains:

I always supported Syria first. Because they have a [large] conventional army and nonconventional weaponry, chemical and biological, and missiles to deliver them. This represents, under certain conditions, an existential threat. And after Syria comes Lebanon [meaning that peace with Syria would immediately engender a peace treaty with Lebanon]. Moreover, the Syrian problem, with all its difficulties, is simpler to solve than the Palestinian problem. And reaching peace with Syria would greatly limit the Palestinians’ ability to widen the conflict. On the other hand, solving the Palestinian problem will not diminish Syria’s ability to existentially threaten Israel.

Barak says that this was also Rabin’s thinking. But he points out that when he took office, he immediately informed Arafat that he intended to pursue an agreement with Syria and that this would in no way be at the Palestinians’ expense. “I arrived on the scene immediately after [Netanyahu’s emissary Ronald] Lauder’s intensive [secret] talks, which looked very interesting. It was a Syrian initiative that looked very close to a breakthrough. It would have been very irresponsible not to investigate this because of some traditional, ritual order.”

The Netanyahu-Lauder initiative, which posited an Israeli withdrawal from the Golan Heights to a line a few kilometers east of the Jordan River and the Sea of Galilee, came to naught because two of Netanyahu’s senior ministers, Sharon and Defense Minister Yitzhak Mordechai, objected to the proposed concessions. Barak offered then President Hafiz Assad more, in effect a return to the de facto border of “4 June 1967” along the Jordan River and almost to the shoreline at the northeastern end of the Sea of Galilee. Assad, by then feeble and close to death, rejected the terms, conveying his rejection to President Clinton at the famous meeting in Geneva on March 26, 2000. Barak explains,

Assad wanted Israel to capitulate in advance to all his demands. Only then would he agree to enter into substantive negotiations. I couldn’t agree to this. We must continue to live [in the Middle East] afterward [and, had we made the required concessions, would have been seen as weak, inviting depredation].

But Barak believes that Assad’s effort, involving a major policy switch, to reach a peace settlement with Israel was genuine and sincere.

Barak appears uncomfortable with the “revisionist” charge that his body language toward Arafat had been unfriendly and that he had, almost consistently during Camp David, avoided meeting the Palestinian leader, and that these had contributed to the summit’s failure. Barak:

I am the Israeli leader who met most with Arafat. He visited Rabin’s home only after [the assassinated leader] was buried on Mount Herzl [in Jerusalem]. He [Arafat] visited me in my home in Kochav Yair where my wife made food for him. [Arafat’s aide] Abu Mazen and [my wife] Nava swapped memories about Safad, her mother was from Safad, and both their parents were traders. I also met Arafat in friends’ homes, in Gaza, in Ramallah.

Barak says that they met “almost every day” in Camp David at mealtimes and had one “two-hour meeting” in Arafat’s cottage. He admits that the time had been wasted on small talk—but, in the end, he argues, this is all part of the “gossip,” not the real reason for the failure. “Did Nixon meet Ho Chi Minh or Giap [before reaching the Vietnam peace deal]? Or did De Gaulle ever speak to [Algerian leader] Ben Bella? The right time for a meeting between us was when things were ready for a decision by the leaders….” Barak implies that the negotiations had never matured or even come close to the point where the final decision-making meeting by the leaders was apt and necessary.

Barak believes that since the start of the intifada Israel has had no choice—“and it doesn’t matter who is prime minister” (perhaps a jab at his former rival and colleague in the Labor Party, the dovish-sounding Shimon Peres, currently Israel’s foreign minister)—but to combat terrorism with military force. The policy of “targeted killings” of terrorist organizers, bomb-makers, and potential attackers began during his premiership and he still believes it is necessary and effective, “though great care must be taken to limit collateral damage. Say you live in Chevy Chase and you know of someone who is preparing a bomb in Georgetown and intends to launch a suicide bomber against a coffee shop outside your front door. Wouldn’t you do something? Wouldn’t it be justified to arrest this man and, if you can’t, to kill him?” he asks.

Barak supported Sharon’s massive incursion in April—“Operation Defensive Wall”—into the Palestinian cities—Nablus, Jenin, Bethlehem, Ramallah, Qalqilya, and Tulkarm—but suggests that he would have done it differently:

More forcefully and with greater speed, and simultaneously against all the cities, not, as was done, in staggered fashion. And I would argue with the confinement of Arafat to his Ramallah offices. The present situation, with Arafat eyeball to eyeball with [Israeli] tank gun muzzles but with an in-surance policy [i.e., Israel’s promise to President Bush not to harm him], is every guerrilla leader’s wet dream. But, in general, no responsible government, following the wave of suicide bombings culminating in the Passover massacre [in which twenty-eight Israelis were murdered and about 100 injured in a Netanya hotel while sitting at the seder] could have acted otherwise.

But he believes that the counter-terrorist military effort must be accompanied by a constant reiteration of readiness to renew peace negotiations on the basis of the Camp David formula. He seems to be hinting here that Sharon, while also interested in political dialogue, rejects the Camp David proposals as a basis. Indeed, Sharon said in April that his government will not dismantle any settlements, and will not discuss such a dismantling of settlements, before the scheduled November 2003 general elections. Barak fears that in the absence of political dialogue based on the Camp David–Clinton proposals, the vacuum created will be filled by proposals, from Europe or Saudi Arabia, that are less agreeable to Israel.

Barak seems to hold out no chance of success for Israeli–Palestinian negotiations, should they somehow resume, so long as Arafat and like-minded leaders are at the helm on the Arab side. He seems to think in terms of generations and hesitantly predicts that only “eighty years” after 1948 will the Palestinians be historically ready for a compromise. By then, most of the generation that experienced the catastrophe of 1948 at first hand will have died; there will be “very few ‘salmons’ around who still want to return to their birthplaces to die.” (Barak speaks of a “salmon syndrome” among the Palestinians—and says that Israel, to a degree, was willing to accommodate it, through the family reunion scheme, allowing elderly refugees to return to be with their families before they die.) He points to the model of the Soviet Union, which collapsed roughly after eighty years, after the generation that had lived through the revolution had died. He seems to be saying that revolutionary movements’ zealotry and dogmatism die down after the passage of three generations and, in the case of the Palestinians, the disappearance of the generation of the nakba, or catastrophe, of 1948 will facilitate compromise.

I asked, “If this is true, then your peace effort vis-à-vis the Palestinians was historically premature and foredoomed?”

Barak: “No, as a responsible leader I had to give it a try.”

In the absence of real negotiations, Barak believes that Israel should begin to unilaterally prepare for a pullout from “some 75 percent” of the West Bank and, he implies, all or almost all of the Gaza Strip, back to defensible borders, while allowing a Palestinian state to emerge there. Meanwhile Israel should begin constructing a solid, impermeable fence around the evacuated parts of the West Bank and new housing and settlements inside Israel proper and in the areas of the West Bank that Israel intends to permanently annex (such as the Etzion Block area, south of Bethlehem) to absorb the settlers who will be moving out of the territories. He says that when the Palestinians will be ready for peace, the fate of the remaining 25 percent of the West Bank can be negotiated.

Barak is extremely troubled by the problem posed by Israel’s Arab minority, representing some 20 percent of Israel’s total population of some 6.5 million. Their leadership over the past few years has come to identify with Arafat and the PA, and an increasing number of Israeli Arabs, who now commonly refer to themselves as “Palestinian Arabs,” oppose Israel’s existence and support the Palestinian armed struggle. A growing though still very small number have engaged in terrorism, including one of the past months’ suicide bombers. Barak agrees that, in the absence of a peace settlement with the Palestinians, Israel’s Arabs constitute an irredentist “time bomb,” though he declines to use the phrase. At the start of the intifada Israel’s Arabs rioted around the country, blocking major highways with stones and Molotov cocktails. In response, thirteen were killed by Israeli policemen, deepening the chasm between the country’s Jewish majority and Arab minority.

The relations between the two have not recovered and the rhetoric of the Israeli Arab leadership has grown steadily more militant. One Israeli Arab Knesset member, Azmi Bishara, is currently on trial for sedition. If the conflict with the Palestinians continues, says Barak, “Israel’s Arabs will serve as [the Palestinians’] spearpoint” in the struggle:

This may necessitate changes in the rules of the democratic game …in order to assure Israel’s Jewish character.

He raises the possibility that in a future deal, some areas with large Arab concentrations, such as the “Little Triangle” and Umm al-Fahm, bordering on the West Bank, could be transferred to the emergent Palestinian Arab state, along with their inhabitants:

But this could only be done by agreement—and I don’t recommend that government spokesmen speak of it [openly]. But such an exchange makes demographic sense and is not inconceivable.

Barak is employed as a senior adviser to an American company, Electronic Data Systems, and is considering a partnership in a private equity company, where he will be responsible for “security-related” ventures. I asked him, “Do you see yourself returning to politics?” Barak answered,

Look, the public [decisively] voted against me a year ago. I feel like a reserve soldier who knows he might be called upon to come back but expects that he won’t be unless it is absolutely necessary. But it’s not inconceivable. After all, Rabin returned to the premiership fifteen years after the end of his first term in office.

At one point in the interview, Barak pointed to the settlement campaign in heavily populated Palestinian areas, inaugurated by Menachem Begin’s Likud-led government in 1977, as the point at which Israel took a major historical wrong turn. But at other times Barak pointed to 1967 as the crucial mistake, when Israel occupied the West Bank and Gaza (and Sinai and the Golan Heights) and, instead of agreeing to immediate withdrawal from all the territories, save East Jerusalem, in exchange for peace, began to settle them. Barak recalled seeing David Ben-Gurion, Israel’s founder and first prime minister (1948–1953 and 1955– 1963), on television in June 1967 arguing for the immediate withdrawal from all the territories occupied in the Six- Day War in exchange for peace, save for East Jerusalem.

Many of us—me included—thought that he was suffering from [mental] weakness or perhaps a subconscious jealousy of his successor [Levi Eshkol, who had presided over the unprecedented victory and conquests]. Today one understands that he simply saw more clearly and farther than the leadership at that time.

How does Barak see the Middle East in a hundred years’ time? Would it contain a Jewish state? Unlike Arafat, Barak believes it will, “and it will be strong and prosperous. I really think this. Our connection to the Land of Israelis is not like the Crusaders’…. Israel fits into the zeitgeist of our era. It is true that there are demographic threats to its existence. That is why a separation from the Palestinians is a compelling imperative. Without such a separation [into two states] there is no future for the Zionist dream.”

This Issue

June 13, 2002

-

*

The New York Review, August 9, 2001.

↩