In the winter, the early mornings in Cairo are almost cool. The pollution, which normally hangs over the streets like a heavy yellow blanket, is light and at this hour the city is still and quiet. Long before it is properly day, the asylum seekers gather at the gates of the offices of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. There are the Dinkas of Sudan with their very long legs, and the elegant high-cheek-boned Somalis; some of the Sierra Leoneans have no arms or hands, the rebels there having decided that mutilating civilians is an effective way of terrorizing those who might be tempted to support the government.

Then there are the Ethiopians, whose ancient allegiance to Haile Selassie has branded them as traitors to the regimes that followed his, and men and women from Rwanda and Burundi, who have somehow managed to escape the killings, and other Sudanese, dissident survivors of torture in Khartoum’s security headquarters. They come at dawn to wait, in the hope that their names may feature on the new lists of those called for interview to determine whether or not they will be recognized as bona fide refugees, with a justified fear of persecution if they return home; or in the fear that they may learn that their appeal has failed and their file is closed, so that the future contains only statelessness or deportation.

The politics of the modern refugee world are not on their side. By the early 1990s, Africans seemed to be on the move, running from the civil wars that are consuming the continent, crossing from one country to another in search of sanctuary, seeking recognition under the 1951 Refugee Convention and its 1967 Protocol, which alone can confer a measure of protection, a little money, and the possibility of eventual resettlement in another country. According to UNHCR, the long wars of borders and ethnic supremacy have in recent years turned some 13 million Africans into displaced people. Many have gone to camps in Kenya and Tanzania; others live along the borders of Sierra Leone, Guinea, and Liberia. But a steady flow have migrated north, drawn by Egypt’s open door policy, not knowing that Egypt has neither the means nor the intention of looking after those they so hospitably allow in, and that the rest of the world has no plans to give them refuge either. Cairo, a city with one of the biggest refugee populations in the world, has become a waiting room. Neither beginning nor end of their odyssey, Cairo is where the international undertakings toward those who seek asylum are most clearly failing, and where the deficiencies of the UN agency set up fifty years ago this past December to care for them are most visibly exposed.

Most countries—the United States and Britain among them—carry out their own procedures for deciding who is and who is not a refugee, but Egypt is one of over fifty countries scattered all over the world who do not, whether because, like Pakistan, they have not signed the Refugee Convention, or, like Togo, Lebanon, and Egypt itself, they have simply relinquished the task to UNHCR. Throughout the 1990s, the asylum seekers kept on coming to Cairo, driven north by brutality, and since the numbers were manageable, many were sent abroad to new lives in the West after their interviews, while others were more or less absorbed by Cairo. But after the war in Sudan intensified, and fresh fighting broke out in Ethiopia, Somalia, Liberia, and Sierra Leone, their numbers grew ever more rapidly. They came to Egypt by a hundred different routes, most of them teenagers and young women with small children, single men and families, on foot, by train, on trucks and steamers and even on camels, from fifteen different African countries, believing that Egypt would be the first step toward a future, and that their past, as victims of the savagery of modern war, was somehow their passport to that future.

No one today has any idea how many asylum seekers and refugees are waiting in Cairo. There may be 200,000, or 300,000, or even half a million. In all, there are people from twenty-seven countries. There are, first of all, some 90,000 Palestinians, who arrived in waves over the years and whose position, as Arabs in another Arab country, has always been different, governed by the political negotiations over the future of Palestinians generally in the Middle East. The Ethiopians and the Somalis are said to number about 5,000 each; the Sierra Leoneans are far fewer, their journeys north being precarious and complicated. By far the largest number—perhaps as many as a quarter million or more—are Sudanese, most of them Christians from the South, arriving by boat from Wadi Halfa to Aswan, and then the night train to Cairo. Like mirrors to the world’s political upheavals, the successive waves of new arrivals reflect each new civil war, each fresh outbreak of fighting, each military coup.

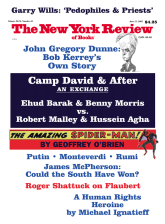

Advertisement

Not long ago, faced with a backlog of well over 10,000 first interviews and a waiting list dating back over eighteen months, UNHCR decided to recruit an extra six interviewers to help the five resident ones in Cairo make a fresh start. But world events flowed against them. Africa’s conflicts grew nastier. UNHCR’s worldwide budget was cut from over a billion dollars in 1999 to $852.9 million in 2001 because the ten principal donor countries felt short of cash themselves: the US, for instance, gave $293 million in 1999, and dropped to $244 million in 2001. And Africa has been the continent worst affected by the cuts. Constantly losing ground, the staff in Cairo have watched their waiting list grow longer, so that at the end of 2001 it stood at over 14,000 first interviews, with 4,000 appeal cases piled in boxes in the corridors, for the few minutes when the lawyers find time to review a file. They are said to complete fifty-six new interviews a week. Less than a third of those applicants will be accepted as bona fide refugees, and only some will receive monthly payments, and, even then, the amount of money available to help them has declined by nearly half in four years.

For the rest, for those who wait and those who are turned down, there is no money, no work permit, no schooling, no free health care, and nowhere to live. A few find occasional work in the underground economy, where, having no papers, they are grossly underpaid; some of the women take jobs as nannies and maids; the others live day by day, sharing among themselves, begging, often going hungry. In one derelict apartment in the city center in November, twelve young African men were sharing two rooms, all living off the $45 monthly allowance received by the only one among them who is a recognized refugee. It is not surprising, then, that the pressures on UNHCR, once revered for its mandate of protection but in Egypt occupying the anomalous and contradictory role of both prosecution and defense, have become insupportable, and that the atmosphere is one of growing prickliness and paranoia. It is not helped by the fact that the Refugee Convention is the only major human rights treaty in which no effort is made to ensure that states are held accountable for what they have signed up to do.

In 2000, 3,057 refugees left Egypt for new lives in seven Western countries. Of these, 2,719 went to the United States, which carries out its own second, detailed set of interviews before letting anyone in. Canada took 105, Britain 10, and Norway 1. After September 11, President Bush refused to set America’s quota for 2002, and for a while there was apprehension throughout the refugee world that the gates to America would never open again. But on November 21 came the announcement that a total of 70,000 refugees from all over the world would be taken in, a fall of some 10,000 from the figure for 2000.

Inside UNHCR’s offices in Cairo, where only those called for an interview ever penetrate, there is an air of embattlement. Doubtless few of the eleven young Egyptians employed to vet cases can enjoy pronouncing on whether the violence people suffered constitutes a degree of persecution extreme enough to make return too dangerous—the standard for deciding whether they qualify officially as refugees. In this daily listening for the nuances of deceit, the little lies that will mark a claim as false, something of UNHCR’s noble mandate is being lost, but it is wrong to blame those who listen, hour after hour, to these tales of bloodshed and torture. There are too many cases, too little time. It is not their fault that policies drafted in 1951, long before most of them were born, when the world was emptier, and still reacting to the Nazi atrocities, with room to take in those whom tyrannical states chose to persecute, are not attuned to the subtleties of modern repression.

Not long ago, an Ethiopian asylum seeker called Ayalnesh, who had been in Cairo illegally for some years, his claim having been refused, was picked up by the police and asked for his papers. Since he had none, he was taken to a police lock-up. He was particularly unlucky. The lock-up was more than usually brutal. The cell in which he was held for over a month with fifty others had neither lavatory nor beds, while the food consisted of a single meal a day of bread, thrown into the cell by a guard. He was sexually abused. From here, he was moved to a prison, sharing a cell with many Nigerians being held on drug charges. When he asked to be allowed to contact someone in the outside world, he was told that he had just two choices: a life sentence in an Egyptian jail, or deportation back to Ethiopia.

Advertisement

Deportations from Egypt are almost casual. There is no money to pay for plane fares to Mogadishu or Monrovia. But those who have no papers because they have been rejected by UNHCR are sometimes taken by truck or bus to the border with Sudan, and put across the frontier into the desert. The choice, then, is bleak: between the long journey home to probable persecution, or return to Cairo and fear of rearrest.

One day, the brother of another refugee came to the prison. Through him, Ayalnesh was able to make contact with UNHCR. One of the legal officers agreed to hear his appeal. He was taken, in handcuffs, to the office, where a busy and overworked interviewer made it plain that his appeal was extremely unlikely to succeed. On the way back to prison, he managed to slip his guard and disappear into the crowds. Next day he went back to UNHCR and forced his way into his interviewer’s office. She confirmed that he had indeed been rejected. Having spent the night considering his future, he had decided that he would rather die than spend the rest of his life in an Egyptian jail, and he knew that to return to Ethiopia would mean certain arrest and torture. Ayalnesh had come prepared. When told of the decision he took from his pocket a bottle of bleach and drank it. To his acute distress, he woke up some hours later in a hospital bed, under guard. Again he managed to escape and again he returned to UNHCR, to make one final appeal. This time the interviewer was unwilling even to see him. An interpreter warned him that the police had been called. He ran. Today he lives in hiding in a friend’s room. He has not left the house for many months.

There are thought to be fifty-one Liberians in Cairo; all but four are young men, the youngest seventeen, the oldest twenty-nine. One of them is Mustafa, a twenty-three-year-old teacher. When Mustafa arrived not long ago at the house of his friend, a tailor from Sierra Leone, he found no one there. He was surprised, because his friend was nearly always at home waiting for him with his supper, but he reasoned that the tailor might have had to make a long journey to the other side of Cairo for a fitting with a client. The room looked unusually neat and empty, but his place was laid, and there was dinner in a pot on the stove. On the table sat a brown paper parcel, tied with string. Mustafa sat and waited. When some time had passed, he began to grow anxious. He needed to eat and leave, to find a place to sleep that night; and, this being his only meal of the day, he was hungry. Finally, he ate. Then he waited some more.

It was now that he noticed that the packet had his name on it. He opened it. Inside were a newly made pair of trousers, a shirt, and a tie, folded neatly, with a letter on top. “Dear Mustafa,” it said. “Here is a present for you. Forgive me. I have wanted to tell you every day for many weeks now, but I have been too cowardly. I was chosen for resettlement in Canada. Today I am leaving.” Mustafa took the clothes his friend had made for him, put them on, threw away the frayed and filthy ones that he had been wearing for many months, and went back to the streets. He did not have the $15 a month he would have needed to take on his friend’s room. Unlike him, Mustafa has not even been recognized as a refugee yet.

Mustafa is one of the lost boys of Africa. Though the words have come to be used for the young Sudanese separated from their families during their flight from the civil war, who grouped together and made their way to refugee camps in neighboring countries and eventually to the United States, Cairo is full of lost boys, though most are no longer boys now but young men, from Sierra Leone and Liberia, Ethiopia and Eritrea, Sudan, Guinea, the Ivory Coast, Rwanda, and Burundi. Most are orphans. Some were child soldiers. If the lost boys have something in common, beyond a look of stunned and mistrustful defeat, a sort of hooded inwardness, it is that they have all witnessed acts of unconscionable cruelty, which they alone, out of their large families, have inexplicably survived.

The brightest boy in a family of Mendes—one of Liberia’s sixteen ethnic groups—born to the four wives of a prosperous farmer in Grand Capemount County, not far from Monrovia, Mustafa was the son chosen for further education and sent away to Sierra Leone. He was a studious boy and he learned good English and Arabic. When he was seventeen, he went home to teach in the local school and prepare to succeed his father as village elder. He was at home, with his pregnant new wife, sixteen-year-old Zainab, when Liberia’s civil war brought killers to Grand Capemount County. These soldiers wanted no elders and no educated Mendes in the new Liberia they planned under their leader, Charles Taylor, a man of mixed indigenous Gola and American Liberian parents, by whom the Mendes, like another ethnic group, the Mandigos, are regarded as enemies to be destroyed. The killing was slow and deliberate. First the women and the girls, after being raped; then the elders, their arms and legs chopped off with machetes; then the young men, shot with Kalashnikovs. Mustafa, in a line with four of his brothers, was the last. By the time the soldiers reached him, an officer had arrived. The killing was stopped.

Mustafa fled. Three days later, at the border with Sierra Leone, he found his wife; she had been raped twice but had not lost the baby. They crossed the frontier, and wandered in the bush, eating grass and roots, with his wife’s mother and a little girl of five, found abandoned along the way, whose parents had been murdered in front of her. One day rebels—for bands of soldiers roamed both sides of the border—caught his mother-in-law as she was gathering berries; they raped and mutilated her, and, in great pain, she died. Then Mustafa was captured, slapped about, scarred with the blade of a bayonet. But the baby, which was born under a tree soon afterward, survived, and they pressed on, hiding in the bushes, begging food from villagers. On the outskirts of Monrovia, they met a friend of Mustafa’s father, a Lebanese trader, who, knowing that Mustafa could not survive for long in a country run by Charles Taylor’s men, bought him a plane ticket and a visa for Egypt. He flew to Cairo, exhausted by months of fear.

That was three years ago. Today Mustafa is still alone in Cairo, stateless, without papers, work, a home, or his family. UNHCR has interviewed him and decided that he does not have a valid claim to be a refugee. He believes Zainab and the children have fled over the border into Guinea, where rape and casual murder are common. Mustafa is slowly shedding his hopes, one by one. He has accepted that he has nowhere to sleep, but has to move from week to week to the floors of other refugees’ rooms, always hiding, knowing that if he is picked up by the police without papers he may be deported; he has understood that he will still have to wait, perhaps for years, for UNHCR to decide whether or not what he witnessed and endured amounts to “justified fear of persecution”; he has accepted that he will find no work other than an occasional day as a laborer in the underground economy, and that he will be forced to beg and scrounge to keep alive.

Among the small community of Liberian lost boys he is seen as a loner. He prefers to put his energy into his dreams, alongside which Cairo, with its overcrowding and its incessant noise, its poverty and racism, its bullying police and indifferent aid workers, is a passing nightmare. Like many other Africans, he will not learn Egyptian Arabic, for to do so means that he has accepted that he will never leave. And so he does not seek out the company of the other Liberians, like Mohamed, a tall boy with a moon-like face who watched his adoptive mother’s head kicked around like a football, or Abu, the boy soldier, who was made to slit open a pregnant woman’s stomach. What these lost boys have seen and been forced to do is not something many care to talk about. “I prefer not to be reminded of the past,” Mustafa told me when I talked to him last November. “I have to believe that I will have a new life, one day, or I will go mad.” Like all the black Africans in Cairo I talked to, he has many stories of being shouted at, called names, even physically attacked; to be black in Cairo is to live in permanent apprehension of racial slights and attacks.

Despair, fear, memory, and expectations endlessly deferred rule in the quicksands of Cairo’s refugee world. Psychiatrists say that it is important for one’s peace of mind to live in the present, to come to terms with daily existence, and neither brood about the past nor attach too much meaning to the future; but the asylum seekers trapped in Cairo today, haunted by memories of loss and savagery, seduced by a longing for a world they perceive as stable and fulfilling, cannot accept the present. Cairo is a prison sentence, to be endured because there is no option. “The problem for refugees here,” a young man told a church worker not long ago, “is that they have no real existence: they live in their head.”

Like Mustafa, few Africans will consider learning Arabic: it is too potent a symbol of failure. The few Africans lucky enough to have the desperately desired blue refugee card are not always the happiest. They do not suffer the terrors of sudden arrest, but resettlement can take many years; the waiting becomes painful enough. There have been an unestimated number of suicides, people unable to wait any longer; they have used up their courage on their torturers and their journey to safety. When the refugees decide to die, they do so by jumping from the balconies of Cairo’s tall buildings; not long before I was there in November, a ten-year-old boy killed himself this way.

Cairo is not just one of the most polluted cities in the world. It is dirty, intensely overcrowded, broken down, and full of rubble, with roads built up on legs above other roads in an attempt to dispel the traffic jams that paralyze the city all day and most of the night. Occasionally, between the brick and the cement, you catch glimpses of filigreed minarets, delicately carved porticoes and arcades, stately façades and the traces of sumptuous courtyards, an earlier Cairo of the Islamic master craftsmen and Coptic merchants. It is the utterly derelict nature of the city today that partly makes possible its absorption of so many refugees and the fact that so many entrepreneurs keep constructing identical cinder-block buildings in ever-widening circles around the city’s edges, leaving the last layer always unfinished, so that more can be added year by year. From the top floors of the buildings along the Nile, on the rare moments when the smog lifts and the setting sun lights the horizon, you can see the Pyramids in Giza, framed by the jagged edges of unfinished blocks. Wherever the buildings are most derelict, the electricity supplies most sporadic, the water least reliable, there the refugees live.

Asylum seekers with families prefer to live in shantytowns on the outskirts of Cairo, where women with small children, whose husbands have been killed, share rooms without light or water. TB is endemic among these families; the children have open sores and scabies; they cough and scratch constantly. They do not go to school, and a whole generation is growing up illiterate. When the Sudanese women find work as maids, they lock the children for safety into the almost empty, dusty, box-like rooms, where they lie on blankets on the dirt floor. Apart from the shafts of light that filter through cracks in the door, it is quite dark; they stay there all day. At Arba Nous, where the desert begins, four hundred Sudanese families live and wait. At least three hundred will never get away.

The refugees are not absolutely without help. There is something in the utter desolation and loss of the refugee existence, the courage of the stories of endurance, that strikes a chord among those drawn to the world of human rights. A dozen or so young lawyers, both Egyptian and foreign, have gathered around Egypt’s fragile human rights movement to struggle to find answers to a situation that appears more intractable with every passing week. In shabby offices in various parts of the city they help the asylum seekers with their testimonies so that no opportunity will be lost when the date for an interview with UNHCR finally arrives. There are a few doctors who, in their spare time, treat those who have been most profoundly tortured and worry about increasing alcoholism among the men and how to alleviate the profound depression that afflicts so many refugees. But while the help of these few doctors and lawyers goes impartially to Muslims and Christians, what little material assistance is available goes almost exclusively to Christians. The Islamic world, which has its own and generous principles about charity, concentrates, in Cairo, on the many poor Egyptians. The Muslim refugees—the numbers are impossible to come by—are the most bereft of all.

In the great modern Coptic cathedral in Abbassiya, Father Anastasi gives money to the most destitute Sudanese families and sends his deacons to the shantytowns with mattresses and blankets; not far away, in Sakakiny, Father Claudio of the Sacred Heart Church runs a school for a thousand Sudanese children. At All Saints Cathedral in Zamalek, among some doctors and teachers, there is a woman who has decided that the best way to help those traumatized by what has happened to them is simply to sit and listen; and this she does, hour after hour. In Arba Nous, a middle-aged Egyptian Coptic woman runs a small food program. But these people are very few.

As the needs of the many Afghan refugees increase all the time, so Africa’s displaced people are becoming increasingly forgotten. There are too many of them, and no one wants them—not the West, where the effort today is concentrated on keeping them out; not UNHCR, which is battling to meet its obligations while trying to honor its mandate of protection; and certainly not Egypt, whose own weak economy is faltering in the wake of September 11. In Geneva and New York, where governments and UN agencies meet, the great international debates go on, about the future of political asylum, the trading in quotas, the many arguments about mandates and responsibilities, the haggling over economic migrants, the seminars about “irregular movers” and the “internally displaced,” the need to address conflict and human rights violations on the spot, so that fewer people will have to become refugees. And while the talking goes on, the asylum seekers of Cairo wait. “It is those who have been rejected who are worst off,” says Barbara Harrell-Bond, emeritus professor in refugee studies at the American University in Cairo. “In the last four years alone, UNHCR has made some 20,000 people illegal in Egypt.” These rejected people, as she points out, can neither go home, for fear of persecution or torture, nor leave to go elsewhere, for they have no passport, nor are they officially allowed to stay. They are truly in limbo.

Not long ago a Sudanese man, carrying a small girl in his arms, managed to get past the guards at UNHCR and into the office of a member of the staff. The child was crying loudly. The man was also crying. Arriving before the interviewer’s desk, he drew back the skirt of the girl’s dress and pointed to her legs: they were covered in open, bleeding, infected sores. “Help me,” he said to the woman. “Help me to do something, help me to get her to a doctor.” The woman, it seems, sat frozen, speechless. The man grew more agitated and insistent. Still, she did nothing. At last, despairing, beyond endurance, he pulled from his pocket the blue refugee card he had fought so long and so hard to obtain, and tore it in shreds. “I am now,” he cried out, trying to explain an act so symbolic and so momentous in words that nothing could make strong enough, “I am now ashamed to be a refugee.”

This Issue

June 13, 2002