On halcyon afternoons back in the Age of Pop, around 1966 or so, college students and other idlers—mostly male, as was and is the tendency—liked to use the latest stack of Marvel Comics as text for a free-floating commentary. The vantage point hardly mattered: aesthetics, Jungian psychology, the dynamics of American social life, the sexual implications of superhero costuming. Marvel’s creations were grist for any kind of rumination, high or low. They provided a shorthand for categorizing personalities and situations (an analogy for almost anything could be found somewhere within the rapidly expanding Marvel Universe), and, most satisfying of all, could be taken as frivolously or as seriously as you wanted. In those days it was not unusual to hear Stan Lee (then still the writer of almost all the company’s dozen or so titles) praised as a protean intelligence of near-Shakespearean dimensions, while the distinctive styles of Marvel’s artists—Jack Kirby, Steve Ditko, Jim Steranko, and many others—fueled hours of discussion about the nature of the line and the employment of space.

Here, many felt, was the real Pop Art, not the appropriation of mass culture by the likes of Lichtenstein and Warhol but a sophisticated reinvention of that culture by longtime veterans of its lowliest reaches. The simplistic charms of old-style superhero comics, with their infantile motivations and threadbare fantasy worlds, had been revamped by Stan Lee and his colleagues into an elaborate playing-out of the genre’s possibilities. Their superheros were self-conscious, plagued by doubts, subject to irrational obsessions, and the increasingly complex narratives in which they interacted were a knowing encyclopedia of all the elements of adventure serial and soap opera. Their main characters—the Fantastic Four, the Incredible Hulk, Dr. Strange (Master of the Mystic Arts), Iron Man, Thor, Sub-Mariner, and, most popular of all, Spider-Man—each had his own emotional shadings and fetishistic peculiarities. Best of all, the proceedings were bathed in a humor which, if not deathlessly witty, gave the proceedings a reliably jaunty cadence: “Though there be many writers, none but Stan Lee could have penned this tale! Though there be many artists, none but Steve Ditko could have drawn this tale! Though there be many letterers, none but Artie Simek was available when we needed him!”

Marvel Comics were overtly formulistic, drawing attention to their visual and narrative devices, and interlarding even the most portentous scenes with wisecracks from the sidelines. The reader was constantly reminded that the story was being invented from one frame to the next, and the result was a sense of complicity between reader and artist. At least at the outset, before they too evolved into a gigantic corporate enterprise, Marvel Comics were perceived as an antidote to the squareness and predictability of mass entertainment. At once good-natured and anti-heroic, they preserved the spirit of seat-of-the-pants inspiration associated with pulp magazines and B-movies; they had something of the free-flowing comic invention of the early days of Mad magazine, coupled with a serious absorption in the evolving mythology of their characters. If not homemade, they seemed at least made in a very small, congenially noisy workplace, full of jokes, kibitzing, and sudden bursts of collective enthusiasm. (In fact, the myth of such a workplace, as conveyed in the asides and intros of the episodes, may have been Stan Lee’s most convincing creation.)

And then there was the art. The stories were good for one go round, but the graphics often became permanent points of reference. A comic book was like a movie you could hold in your hand, contemplating the action as a series of immobilized moments of tension: in some ways it was better than a movie, because of the scope it offered to expand imaginatively on what the page offered. Even aside from the difficulties of staging the fanciful combats and intergalactic confrontations of the comics (now solved after a fashion by the advent of computerized special effects), it seemed unlikely that any movie could ever capture the way the best comics could feel lightweight and monumental in the same instant, while always remaining the direct handwritten evidence of a human touch. What movies gained in palpability they lost in the buoyancy of a world made with pen and ink.

Sam Raimi’s Spider-Man, which became the latest warm-weather blockbuster to break all previous first-weekend attendance records, adheres rather faithfully to the letter of the original comic book. Much of it is a straightforward recapitulation of the origin of Spider-Man, as recounted on his first appearance in Amazing Fantasy in August 1962: the transformation of serious, socially awkward science major Peter Parker by the bite of a radioactive (in the movie, genetically altered) spider into a superhero capable of climbing walls, swinging from building to building on webs, and sensing the approach of danger with his “spider sense.” The catch was that he was never quite able to make his peace with that transformation. At the time the idea of a teenage superhero was a novelty, and the idea of a neurotic teenage superhero, troubled by recurrent feelings of guilt and inadequacy, seemed positively revolutionary.

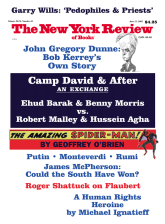

Advertisement

The crucial plot point in the original episode was that Peter Parker’s initial burst of unwonted arrogance on receiving his spider powers led through a sequence of ineluctable coincidences to the death of his beloved Uncle Ben. The notion of a moral lapse (his momentary hubris) that could never really be atoned for gave the comic book its air of perpetual dissatisfaction; being Spider-Man was not only a burden in itself but a perpetual reminder to the hero of his own shortcomings, a kind of penance. There was always the possibility that he would fail again, and so he was condemned to a vigilant monitoring of his own reactions and impulses. In such a situation an unqualified sense of triumph was by definition impossible. In its own goofy way, The Amazing Spider-Man acknowledged the tragic sense of life.

Raimi is finely attuned to those nuances, but what once were unanticipated tweaks of characterization have over time become nearly solemn. It was amusing in the mid-Sixties to juxtapose Stan Lee with Shakespeare, to find an analogy between Shakespeare’s multifariousness and Lee’s populous mythology, and contrariwise between Lee’s sure instinct for entertainment and Shakespeare’s unwavering theatricality. But that doesn’t mean that Spider-Man can assume the gravitas of Lear or Hamlet, even with Danny Elfman’s somber theme music stirring up a mood of troubled pensiveness. The problem is partly one of scale. If you compare Steve Ditko’s art for that first Spider-Man episode with the visual look of Raimi’s film, it’s like putting the drawing on a 1950s matchbox next to one of the immense digital displays that now define the landscape of Times Square. Ditko’s boxy little frames, however, have a quirky vigor and caricatural grace that let us know a live hand is tracing them, and when those scrawny miniature figures are forced to contend with moral dilemmas they acquire a quixotic stature. Such is the odd intimacy that comics can command.

Raimi’s film, on the other hand—and the same could be said of most such contemporary films—looks like what it is, a work of large-scale industry. If you admire it, it’s in the same way you might admire a World’s Fair or a suspension bridge. The Amazing Spider-Man came up from the bottom; not many people were looking for original invention in ten-cent comics in 1962. Spider-Man, the movie, descends from above, trailing clouds of magazine covers and licensed toys, and thus has a ponderousness its model altogether lacked. The scenes of digitally simulated combat—like most scenes of digitally simulated combat—have little more life to them than the rapidly shifting arrangements of numbers on the screen of an electronic calculator. Not for one moment do we believe that any entity is colliding with any other entity: the heft of actual being and actual contact is replaced by a terminally weightless play of microdots. The action scenes certainly lack the humorous inventiveness of the whirling and careening body parts in Sam Raimi’s breakthrough feature, the low-budget horror picture The Evil Dead (1983), a movie whose nonstop carnival of demonic possession in a haunted cabin was much closer in its freewheeling spirit if not its gruesome content to Marvel Comics at their best.

It must also be said that the enactments of aerial assault—for instance in the endlessly protracted scene where the Green Goblin, Spider-Man’s psychotic nemesis, massacres the board of directors of a technology corporation in the midst of a public festival—have a brutality of tone that nearly sinks the mood of fantasy. Perhaps it is only because I watched the film in a recently reopened movie theater directly overlooking Ground Zero that such evocations of urban structures demolished by flying objects felt less than diverting. At any rate I did not feel alone in an audience that seemed clearly unexhilarated by the numbing digitalized intimations of bludgeoning impact.

The paradox of digital effects is that the more real they look the less real they feel; the most primitive models and painted backdrops of the early silent era convey far more of a sense of events occurring in actual space, and thus far more possibility of emotional consequence. Like the digital Rome of Gladiator, which never looked like anything other than an architect’s blueprint, the aerial ballets of Spider-Man lack a crucial element: air. Raimi’s film is something of an epic of New York, but despite all the elaborate (and elaborately altered) location work it can’t help feeling like anything more than a simulacrum.

Advertisement

Marvel’s original Spider-Man by contrast got much of its edge from the intersection of comic-book absurdity with the commonplaces of New York in the Lindsay years. No-nonsense cab drivers, hot dog stands, The Ed Sullivan Show: it was amid such familiar cultural markers that Spider-Man waged his annihilating battles against the Vulture or the Kingpin or Doctor Octopus. It hardly mattered that New York was depicted in a thoroughly stylized fashion; the fact that it was indicated at all was as bracing a blast of reality as the steam from a Con Ed work site. J. Jonah Jameson, the short-tempered, cigar-chewing newspaper publisher (who gets sadly short shrift in the movie version), embodied something of the ambience of those unventilated back rooms where you could imagine the old-time comic books being cranked out.

Raimi is on much surer ground with the soap opera elements—Peter Parker’s invalid aunt, his girlfriend troubles, his simmering jealousies and resentments—that were probably the secret reason for the comic’s special appeal. There are even moments when Raimi seems to be evoking the mood of curdled domesticity that he cultivated to such ominous effect in the underrated thriller A Simple Plan, as if to defy the inevitable moment of heartwarming emotional outpouring which all American movies now require. The Amazing Spider-Man was essentially a romance comic disguised as a superhero comic, a secret feminization of the man-of-steel tradition, and Tobey Maguire’s incarnation of Peter Parker has a cuddly charm that will doubtless lead to many sequels, even if his performance lacks the quality of nerdy anguish so well expressed by Steve Ditko’s primitively expressive artwork. Maguire looks a little too capable of enjoying himself, with the result that it’s hard to believe the final act of romantic renunciation, when he chooses to give up the girl of his dreams to follow a more ascetic path of lonely heroism. Willem Dafoe’s fire-eating performance as the Green Goblin is on the other hand almost too fully achieved; he makes everybody else look as if they’re just rehearsing.

Overall Raimi has done the sort of unimpeachably professional job that means we are probably witnessing the birth of another highly profitable franchise. As an entertainment Spider-Man has pretty much everything it needs; it lacks only that factor of eccentricity, that wild card of random improvisation that made the comics so much fun in the first place. That would of course be too much to expect. If Spider-Man had been filmed back in the Sixties, we might have gotten something like Joseph Losey’s Modesty Blaise (1966) or Mario Bava’s Danger: Diabolik (1967), obtrusive exercises in applying primary-colored Pop Art style to every frame, with results that were eye-popping if not necessarily moving or even absorbing; if it had been filmed in the Seventies or Eighties it would probably have been a tacky production filmed on location in a developing country and jazzed up with a little gratuitous nudity or a bit of martial arts. What we get now is Spider-Man as narrative theme park, cautious, respectful, planned down to the last dangling coil of webbing, realized by the usual coordinated teams of disciplined professionals, and pre-sold with the skill that is an art in itself to a global audience that will wake up to find that this is what it was waiting for all along.

This Issue

June 13, 2002