PANIC

Philip Jenkins was a fairly obscure historian until 1996, when reactionary Catholics made him an improbable star. He began his career as a professor of criminal justice at Pennsylvania State University, specializing in the debunking of alleged “crime waves.” For criminological journals he wrote four articles on what he considered the unjustified fear of serial murderers in England.1 In his 1992 book, Intimate Enemies: Moral Panics in Contemporary Great Britain, he broadened his analysis of “constructed” social fears to cover “witch hunts” over Satanism, rape, incest, pedophilia, child pornography, homosexuality, and drugs. In each case an “imaginary menace” is manufactured by “moral entrepreneurs” as a form of “symbolic politics.”

These panics, he argued, are often interconnected: “There is a natural tendency for activists who have been successful in exploiting one fruitful issue to employ similar rhetoric and examples in related causes.” Jenkins calls this phenomenon “problem convergence.” Feminists, for instance, exploit the issues of rape, serial murder, child abuse, and pornography to promote their agenda. The state is often brought in to control these nonexistent threats, creating its own real threat of repression based on hysteria. The British pedophile scare, for instance, involved “a more or less covert assault on homosexual rights.” When the pedophilia involved Anglican choirboys, fears drew upon “a powerful image of anticlericalism.”

After Jenkins had established his libertarian and permissive standards, he made one exception to it in his 2001 book, Beyond Tolerance. Despite his criticism of panic over child pornography, he found one form of real exploitation on the Internet, filmed sexual acts with real prepubescent children. Even this he did not want to outlaw, since bringing in the state is an invitation to repression—current porn- ography laws, for instance, pose a threat to legitimate portrayals of adolescent sexuality like Lolita or American Beauty. Only China and Burma have suppressed child pornography—by suppressing freedom.

Jenkins thinks that much of the panic over child abuse is derived from a confusion of two different things, each going under the same name: pedophilia. For him, real pedophilia (child-love) concerns only prepubescents. He disapproves of this, but says that restraining it may threaten quite different sex acts with postpubescents, which he calls ephebophilia (boy-love). He holds that statutory rape laws should not outlaw such youth-love, since there is nothing in nature (as opposed to local custom) to deny the power of consent to even very young teenagers: in America “the age of consent for girls stood at ten years from colonial times until the 1880s.” Pornography involving teenagers is difficult to distinguish from Gap ads, and therefore from Internet pornography in general, on whose beneficial effects Jenkins is positively lyrical, contrasting it with the false prettiness of mainline pornography:

We can, in fact, argue that the highly democratic and easily accessible nature of sex on the Internet creates a social benefit by so frequently depicting real people, with all their visible flaws and imperfections, rather than the distorted and overidealized imagery that so long characterized X-rated magazines and movies.

He notes with approval that even plain and fat women have become sex stars on the Internet, affecting the norms of female beauty “in a way that many observers would consider highly positive,” since it makes smut more egalitarian. Playboy offered the girl-next-door image. The Internet brings us the slob next door, which Jenkins considers a great step forward.

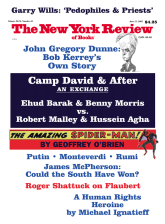

How did this praiser of pornography and boy-love become a hero to reactionary Catholics? The man who has devoted his professional life to denouncing the opportunism of those who create panics became, himself, the occasion for an anti-panic opportunism. Neglecting all the other things he has to say, and the reasons he has for saying things in general, conservative Catholic journals fastened on what they found useful in his 1996 book, Pedophiles and Priests. That book just applied to the American Catholic situation what he had said of secular and Anglican pedophiles in England. Since by his definition all such panics are artificial, one has only to apply the cui bono principle to see who is manufacturing any panic. The principal villains he found in the priest-pedophile crisis of the 1990s were anti-Catholics, greedy lawyers, self-promoting prosecutors, sensationalistic newspapers, therapists seeking clients, and feminists with their “theology of abuse.” He never seems to consider the possibility that the panic was not manufactured, or that many factors impeded rather than promoted the revelation of priestly misconduct. Reluctance to believe, report on, or expose priests is deeply built into American culture.

American bishops and their defenders gladly promoted Jenkins’s claim that there was nothing to the priest-pedophile phenomenon but bad faith on the part of those “exploiting” it. They even said that his testimony was stronger and more disinterested because Jenkins is not a Catholic. With his help they dismissed or minimized the “panic,” which allowed Cardinal Bernard Law and others to continue sending accused priests about their ordinary ministry with the results we have seen in Boston and elsewhere. When Cardinal Law in the 1990s called down God’s judgment on The Boston Globe, he was just putting in his own way Jenkins’s attack on “the political interests of the activists and groups who used the media to project their particular interpretation of the putative crisis.”

Advertisement

WITCH HUNT

Despite the unhappy results of following Jenkins’s lead in the last decade, some conservatives continue to use his method in responding to the current situation. TV commentator Robert Novak repeats on Crossfire that Catholic liberals are just attacking Cardinal Law because of his strict stand against contraception—though it is mysterious why anyone should care about Law’s views when the vast majority of Catholics (up to 80 percent in some polls) ignore them. It is a strange liberal conspiracy against Law that has so many conservative Catholics calling for his resignation—William Buckley, William Bennett, Patrick Buchanan, and Bill O’Reilly among them. Even the far-right Manchester Union Leader has called for the resignation of New Hampshire’s Bishop John McCormack for his collaboration with Law in reassigning accused pedophiles. Others think that people need a liberal “agenda” in order to care about the molestation of the young. (“Agenda” is the current swear word—say anyone has such a thing and he or she is instantly disqualified from expressing an opinion. Apparently only the directionless or clueless are worth listening to.)

Actually, much of the defense of Cardinal Law has come from those not previously thought of as conservatives. The formerly liberal journal Commonweal has editorialized against the panic in a purely Jenkinsian mode, comparing it to “the anti-Communist witch hunts of the early 1950s.”2 Peter Steinfels, a religion editor at The New York Times who is married to the editor of Commonweal, wrote in his paper that Cardinal Law did a good job of cleaning out pedophile priests in the 1990s but made a mistake in not publicizing his effort, which gave lawyers an opportunity for “inflating charges and using the news media to play on public fears and prejudices in the hope of embarrassing the church into settlements.”3 Kenneth Woodward, the formerly liberal Catholic editor at Newsweek, told Don Imus that lawyers specializing in the defense of alleged victims should be ashamed to tell their children how they make their living.

This blackening of accusers’ reputations seems to go beyond a laudable concern for the rights of the accused, and it ignores the fact that only suits by the abused have forced the Church to reveal what was happening. Cardinal Roger Mahony of Los Angeles has latterly been boasting about the comprehensive plan he instituted last year for investigating and exposing pedophilia. He neglects to mention that this detailed eleven-point plan was forced on a reluctant diocese by one priest’s victim who made it a condition of settling his suit.4 He gets credit for not calling the crisis artificial—but only because legal pressure forced him to what he now calls the enlightened position. Woodward and Steinfels must, by the logic of their position, consider that the cardinal has now joined the “witch hunt.”

It is easy to stigmatize lawyers, of course, and some major firms have now taken up cases of alleged abuse. But people with small practices pioneered in bringing these suits, since the prospects of taking on the Catholic Church seemed so dim. The Dallas lawyer Sylvia Demarest took part in the effort that won record damages in a Dallas case in 1997 because she came to know the victims and their families. The jury was so outraged at what it took to be the bishop’s lies in that case that it wrote him a note of rebuke and awarded his priests’ victims $119 million. When the diocese pleaded that this would put undue hardship on it, the victims agreed to accept only a fourth of what was owed to them. But it should be remembered that private settlements involving large sums were sometimes proposed by the bishops, in order to avoid letting juries express their views by exacting even higher penalties and to make silence a part of the bargain, keeping the matter secret. That was the dynamic at play in Cardinal Mahony’s settlement involving new policies as well as an agreed-on sum of money.

There is good reason to fear false accusations, as in the attacks on day care centers that involved very young children with cultivated memory “recovery.” But most of the accusations against priests have not involved children with recovered memory but adolescents struggling to deal with shame and the minatory aura of the Church. The most recent thorough review of findings on pedophile cases in general suggests that about 5 percent of accusations have proved false.5 But that is a survey of cases with both male and female children victims, with both lay and clerical predators. It is probable that the number of false accusations is lower where only boys are at issue, where the pressures against resistance and revelation involve religious authority and familial disbelief in that authority’s errancy, and where a cultural bias against admitting to same-sex molestation is strong. Michel Dorais argues that the latter factor inhibits boy victims of men from speaking out, even where religion does not enter into the crime.6

Advertisement

Dorais also stresses the psychological importance of reaching financial settlements as a form of societal endorsement of their legal complaint’s validity. It is important that some authority endorse their condition, since the pedophiles rarely if ever do—and, in the case of priestly abuse, because the hierarchy has avoided admission or apology short of legal compulsion. Many parents of abused boys asked only for apology and assurance that the priest would be sequestered from children—and some sued only when they found that the apology was minimal or hollow and the assurance of sequestration was a lie. Dorais writes:

Certainly, material compensation cannot soften interior pain. It can, however, allow the seeking out of better services to help the victim face up to what he is going through. It is essential that the damages caused by sexual abuse be fully recognized. Too many abused boys feel that nothing has been done for them and never will be. Paradoxically, if they are to be allowed to turn the page, it must be first recognized that they have been victims.

REAL PEDOPHILIA

One reason the hierarchy’s defenders still rely on Jenkins’s Pedophiles and Priests is that they like the book’s distinction between pedophiles and ephebophiles. Kenneth Woodward in his frequent television appearances rarely fails to stress the importance of this distinction. If “real” pedophilia involves only the abuse of prepubescents, that instantly reduces the number of priests who can be called pedophiles. Those who “just” molest adolescents look less monstrous and even—somewhat—forgivable. As Cardinal Francis George of Chicago said in Rome, there is a difference between a pedophile and a priest who, “perhaps under the influence of alcohol, engages in an action with a 17- or 16-year-old young woman who returns his affection.”7Jenkins writes: “In the Catholic church law, the age of heterosexual consent is sixteen rather than the eighteen common to most American jurisdictions.”

Since the bishops’ defenders are making so much of the pedophile– ephebophile distinction, it is worth taking time to sort out the linguistics of the matter. The word at issue is Greek pais, with the stem paid- (boy) as in boy-training (paideia). Since it is the same word used in “pediatrics” (boy-healing) and “encyclopedia” (circle of boy-training), William Safire says we should pronounce the word “peedophile.” But then he would have to say peedantic and peedagogue. There is no linguistic norm to pronunciation here, only usage. Jenkins tries in Intimate Enemies to distinguish the pedophile from the pederast (or peederast)—the latter as another word for an ephebophile. There is no justification for this in the Greek phenomenon that gave us the words and the concept. The Greeks used paiderastia and paidophilia, with exactly the same meaning, for sexual interest in adolescents. They had, therefore, no need for the term “ephebophile,” which is a modern coinage and should be discarded.

For the Greeks, the adolescent boy loved could be a philos (dear one) as well as an eroåømenos (loved one), and both words referred to an adolescent. Theognis refers to the boy loved as philos, the lover as paidophileåøs, and the bond between them as philia. The word pais did not mean “child” (which was paidion) but “lad” (or sometimes “lass”), one able to acquire paideia, to herd swine (Iliad 21.282), to have sex (Lysistrata 595), to be Zeus’ wine steward (Ganymede). The word was even used, like garçon, for a servant of any age—the same as the old insulting use of “boy” for a black man in the South, or the use of “lads” for a leader’s underlings.

It is said that pedophilia is limited by some modern therapists to mean sex with prepubescents. That may be useful in sorting out different forms of treatment. But that is not the meaning of pedophilia in history nor in the broader culture. Jenkins claimed in Priests and Pedophilia that the National Catholic Reporter began calling priests who have sex with a teenager “pedophiles” as part of a rhetoric of denigration.8 But the word is not an invention of malice—it is used even by those who defend boy-love. See for instance, Harris Mirkin’s article on what he expressly calls pedophilia.9 The rhetorical dodges here are Jenkins’s own.

Admittedly, there is a difference between sex with young people before and after puberty. In the law, of course, they are both acts of sex witha minor. But the coercion is clearly greater with a child, and the adult is more clearly pathological. Nonetheless, the harm done is not of necessity always greater. Sex with a child, heinous though it is, may be for the child part of an inexplicable world not to be connected with other realities. Child psychologists point out that children can learn so much so rapidly because they are ruthlessly efficient in dismissing information not useful to them.10 But Michel Dorais, in his close study of abused boys, argues that abuse of adolescents is especially disorienting because it occurs at a time of challenged identity, uncertain standards, and shadowy guilt. It is all too clearly connected with other realities, mysterious in themselves. Those who argue that most priests’ crimes are with adolescents are actually granting that their memories are more trustworthy, since recovered memories are most questionable when they are recalled (supposedly) from early childhood.

Adolescent guilt and inhibition were especially powerful for Catholic boys raised in a culture of sexual ignorance and guilt. Nuns were reluctant to speak about sex except in vaguely threatening language. Priests were mechanically judgmental in the confessional. The ignorance of the Catholic culture about sex was brought home to me and my wife-to-be in 1959. We were ordered by our parish priest to attend a “Cana Conference,” the lay-taught marriage preparation course set up in most parishes. There we were separated by gender, to be told “the facts of life” by a husband-wife team as if we knew nothing about sex. Besides being warned against contraceptives, we were given how-to tips on happy married life. The men’s group was advised to be tender in hugging and praising a wife, since that was all she was going to get—women are incapable of orgasm. My wife and I were in our twenties, and could afford to laugh at this officially sponsored stupidity. And I’m sure the same was true of most of the eighteen-year-olds attending. But what ignorance could a predatory priest rely on when dealing with fifteen-year-olds in such a culture?

What is shocking in the currently revealed cases is not the number of Catholic priests who have preyed on children—though that is dismaying enough—but the repeated loosing of these predators (whatever their number) for numerous repeated acts on such a vulnerable population as Catholic boys disarmed by benighted instruction or lack of instruction on sexuality. To say that this is not so bad since it is not “real pedophilia” is a further violation and abuse of the victims.

CONSENTING VICTIMS

A serious temptation, for those who (like Kenneth Woodward) favor the fake category of ephebophiles, is to blame the victims, saying that, unlike children, they must have granted some degree of assent to what was done to them. Cardinal George limited his charge of complicity to a sixteen-year-old girl, but a monsignor in Dallas who helped shuffle a pedophile priest from parish to parish went further. Father Robert Rehkemper said of the victims: “They…knew what was right and what was wrong…. Anybody who reaches the age of reason shares responsibility for what they do. So that makes all of us responsible after we reach the age of 6 or 7″—the age at which Catholic children were considered responsible enough to own up to sins in the confessional.11

The monsignor is more permissive even than Jenkins, who at least rules out prepubescents as candidates for consensual sex. But some Catholic apologists are lending tentative support to the Jenkins view of minors’ ability to consent—a position now energetically defended by some. Judith Levin, like Jenkins, dismisses “the pedophile panic” in her book Harmful to Minors. She studies at great length the case of a thirteen-year-old girl who met a twenty-one-year-old man on the Internet, fell in love with him, ran off, and remains true to him, though her parents had the man pursued, tried, and imprisoned, where he might become the victim of sex not as voluntary as hers was. Levin introduces only indirectly and in muted ways the fact that the man involved had been unable to hold jobs, had conceived two children in abusive relations, and had a history of mental disturbance as well as a “fairly hefty sheet of [criminal] charges pending against him.” She thinks it a mitigating rather than an aggravating factor that, despite the nine years’ difference between them, the man was close to the girl’s age “emotionally and intellectually.” Levin thinks that the parents were at fault in persecuting this Romeo and Juliet, in “demonizing” the man, treating him as a monster—as if they had no responsibility for trying to save their daughter from the consequences of an irresponsible choice. Asked by Salon what she would do if her own daughter were in such a situation, Levin said that she would use persuasion on her.

Though Levin is very good on certain aspects of our society’s attitude toward sex—especially on the absurdities of the Republican success in equating sex education in the public schools with abstinence promotion—she often reads evidence selectively. After telling us that we should listen to teens, to find out what they really want, she dismisses a survey that has shown that women regret having sex at an early age. This just shows, according to Levin, how our culture imposes guilt feelings where they are inappropriate. So much for listening.

Harris Mirkin’s case for what he frankly calls pedophilia is that women’s rights and homosexuality were once considered unnatural but then won acceptance, so the same thing is bound to happen to pedophilia. One could as well argue that incest and murder have been considered unnatural, so they are bound to become respectable. Once again, one has to wonder what conservative Catholics are doing in this company. One answer is that they were shepherded there by Philip Jenkins, who seemed to offer their priests an escape from the charge of pedophilia. It looks like a step up for priests to be having sex with “consenting” partners, not helpless children. They are still doing something wrong. But they are not monstrous.

Admittedly, it is possible for an older adolescent who is gay to have a tender relationship with an older man; but the power disparity between the two always makes questionable the quality of consent in the boy and of responsible love in the adult, especially where religious authority is involved. Objections to teacher–student sex, or even to employer–employee sex where the employee is an adult, have a certain force—but not nearly the force that applies between priest and boy. Besides, the cases at issue are ones where the accusers are claiming a measure of coercion, not of trusting love.

THE GAY MENACE

A second temptation for conservatives who adopt an ephebophile strategy—after blaming the victim—is a tendency to think that homosexuality leads to child molestation. If the teenagers are consenting, what is wrong with the act? Conservatives have been quick to say that it is not sex that is wrong but same-gender sex. For them, teen sex acts or adult sex acts are both wrong if they are homosexual acts. In order to blame gay men, some would attribute the abuse cases to the high number of homosexuals in the priesthood. This has assumed a conspiratorial air in right-wing circles. Michael Rose argues, in Goodbye, Good Men, that the priesthood is being tacitly dismantled in seminaries by gay priests who want to destroy the Church’s doctrine not only on sexual matters but on other beliefs.

Calmer Catholics, like Cardinal Avery Dulles, claim that gay and radical people were admitted to the seminaries in the evil Sixties, but that the conservative direction of the present pope is slowly remedying this situation.12 But Rose paints a picture of good and faithful candidates for the priesthood still being turned away from the seminaries or driven out of them. Both the calm and the hysterical conservatives imagine that there is a pool of people in the Catholic populace who do not agree with the 80 percent or so who have rejected the papal teachings. They also neglect the fact that many of the pedophiles apprehended entered the seminary before the Sixties.

There is no reason to think that homosexuality of itself, any more than heterosexuality of itself, makes a man a child molester. But the pressures to cover up priestly molestation are greater in the Catholic Church than in secular life, or in other religions, which do not condemn homosexuality. Other Christian denominations have openly debated the ministry of gays, and some have gone on to admit them as pastors. That kind of open discussion has been aborted for Catholics by the Vatican’s blanket condemnation of all homosexual activity, making gay priests live furtive lives, participating in the cover-up of other things by the hierarchy.

The current scandal is not a sex scandal. It is a dishonesty scandal. It entails what I described, two years ago in my book Papal Sin, as “structures of deceit.” Until the hierarchy can “come clean”—to themselves, to the faithful, to the world—an instinct toward shifted blame and righteous denunciation will stand between it and the truths it claims to preach. The problem is not with the Church, with the people of God, but with those who claim to be the Church, in a structure honeycombed with pretense, hypocrisy, and evasion. The core of solid belief, the common sense of the faithful, the deep belief in the saving truths of the creed, will stand more solid after this clumsy scaffolding of lies thrown up around it has collapsed.

—This is the second of two articles on pedophilia in the Church.

This Issue

June 13, 2002

-

1

“Myth and Murder: The Serial Murder Panic of 1983–1985,” Criminal Justice Research Bulletin, Vol. 3 (1988); “Serial Murder in England, 1940– 1985,” Journal of Criminal Justice, Vol. 16 (1988); “Sharing Murder: Understanding Group Serial Homicide,” Journal of Crime and Justice, Vol. 13 (1991); “Changing Perceptions of Serial Murder in Contemporary England,” Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice, Vol. 7 (1991).

↩ -

2

“The Whole Story,” Commonweal, April 5, 2002.

↩ -

3

Peter Steinfels, “Beliefs,” The New York Times, February 9, 2002.

↩ -

4

William Lobdell, “Diocese’s Policies Reflect Settlement,” Los Angeles Times, April 28, 2002.

↩ -

5

M.D. Everson and B.W. Boat, “False Allegations of Sexual Abuse of Children and Adolescents,” Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Vol. 28 (1989), pp. 230– 25.

↩ -

6

Michel Dorais, Don’t Tell: The Sexual Abuse of Boys translated by Isabel Denholm Meyer (McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2002), pp. 42–48.

↩ -

7

Catherine Caporusso Harman, “NOW Shoots First,” Chicago Tribune, April 27, 2002.

↩ -

8

Jenkins repeated this charge against the National Catholic Reporter in a Wall Street Journal article (March 26, 2002), “The Catholic Church’s Cultural Clash.”

↩ -

9

Harris Mirkin, “The Pattern of Sexual Politics: Feminism, Homosexuality, and Pedophilia,” Journal of Homosexuality, Vol. 37 (1999), pp. 1–24.

↩ -

10

Alison Gopnik, Andrew N. Meltzoff, Patricia K. Kuhl, The Scientist in the Crib: Minds, Brains, and How Children Learn (Morrow, 2000), pp. 45–52.

↩ -

11

Ed Housewright, “Parents of Abused Boys Share Blame in Kos Case, Ex-Diocese Official Says,” Dallas Morning News, August 8, 1997.

↩ -

12

Avery Dulles, S.J., “The Jesuit Enigma,” First Things, April 2002.

↩