To the Editors:

Having been in a Belgian artillery unit in 1940, my limited recollections (like those of Stendhal’s Fabrice of Waterloo) dovetail with Tony Judt’s insightful “Could the French Have Won?” [NYR, February 22, 2001]. We had been trained for World War I. “The artillery never moves; be sure to shoot over the heads of our infantry!” As soon as the Germans unexpectedly crossed the Albert Canal (considered an extension of the Maginot Line) on May 10, 1940, we were confronted with the new tank-plane combination, and were sure all was lost. Morale had been low, especially among Flemish troops—easy prey of Goebbels’s radio propaganda: “Why are you fighting for Belgium, an artificial British creation?”

In accordance with King Leopold III’s policy of neutrality, in September 1939 our guns pointed westward—derided by most of us as one of the more incongruous aspects of the “phony war.” However, one month later we moved close to the Albert Canal to face Germany. The King did not capitulate “precipitatedly,” but had no choice under the circumstances. The reason he was forced to abdicate after the war was his unconstitutional refusal to join his government in London in June 1940.

It does not require “a long chain of one-directional ‘ifs'” to argue that the French could have won in 1936 when Hitler illegally occupied the Rhineland and France could have easily defeated Germany. This opportunity was missed, and the twentieth century took its tragic course.

Felix Oppenheim

Amherst, Massachusetts

To the Editors:

Tony Judt, in his fine review [NYR, February 22, 2001] of Ernest May’s book Strange Victory on France, Germany, and the outbreak of war in 1940, notes that the “eminently respectable Nouvelles économiques et financières” sneered at French Prime Minister Léon Blum as “the Jew Blum,” “our ex–prime minister whose real name is Karfunkelstein.”

Lest readers believe that this “respectable” newspaper knew what it was writing, I would point out that Blum came from a family of Alsatian Jews named Blum that traced its ancestry back at least two centuries. The name Karfunkelstein, allegedly from Bulgaria, was pinned on Blum when he, along with other French intellectuals such as Émile Zola and Jean Jaurès (to name but two), defended Colonel Alfred Dreyfus against French anti-Semites during the Dreyfus affair at the turn of the century.

I should point out that Nouvelles was not the only “respectable” publication to refer to Blum, France’s Popular Front leader after 1936, as “the Jew Blum.” Time magazine, in reports written by foreign editor Laird Goldsborough (no relation), a notorious defender of Hitler and Mussolini, used the same characterization consistently during the period.

James O. Goldsborough

The San Diego Union-Tribune

San Diego, California

Tony Judt replies:

I am grateful to Felix Oppenheim for confirming from his own experience my account of the disasters of 1940. And he is right to take me to task for suggesting that King Leopold’s surrender to the Germans was the chief source of his postwar fall from grace—the affair was a bit more complicated than that. Not only did the Belgian king (in contrast to the Dutch queen Wilhelmina) refuse to join his government in exile, but his subsequent relations with the occupying Germans were a little too accommodating for postwar Belgian comfort. That is why he lost his throne. However, his overhasty capitulation in May 1940 surely contributed—the Belgian military position was hopeless, yes, but Leopold’s failure to consult his allies before abandoning the struggle just made things worse for their retreating armies. This would not be forgotten.

The French could certainly have defeated Germany easily in 1936. But they would not have had to go to the trouble. If France had made clear that it would forcefully oppose Hitler’s remilitarization of the Rhineland in March 1936, the Nazi leader would undoubtedly have withdrawn his outnumbered troops—and he would have lost face, not least with his own skeptical officers. Who knows what might then have happened? But France did not oppose Hitler in 1936 (this is one reason why the Belgians, despairing of their erstwhile ally, declared themselves “neutral” thenceforth, with the absurd outcome noted by Mr. Oppenheim). Indeed, characteristically, France was between governments at the time and on the verge of a huge general strike. The men running French military and political affairs in March 1936 were in many cases those who would be influential in May 1940, not least General Gamelin himself. Their paralysis in 1936 derives from the same sources as their incompetence in 1940, and it is to these, rather than to the accidents of military misadventure in the Ardennes woods, that we must look if we seek to explain the Nazi victory.

I welcome Mr. Goldsborough’s letter. Sadly, the tale does not end in 1940, nor even in 1945. The “Karfunkelstein” myth was still alive in French reference works as late as 1960, according to Pierre Birnbaum in his authoritative account of political anti-Semitism in France (Un Mythe politique: La ‘République juive,’ 1988). A 1946 poll found that 43 percent of French respondents did not believe that a citizen of Jewish origin could be an “authentic” Frenchman. Léon Blum knew his country well—in 1946 he declined Charles de Gaulle’s invitation to head a government of postwar recovery. You need someone else, he replied—“I have been the most hated man in France.”

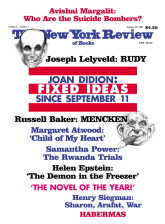

This Issue

January 16, 2003