To the Editors:

“In the study of anything outside human affairs, including the study of complexity, it is only simplicity that can be interesting.” This is Steven Weinberg’s credo [“Is the Universe a Computer?” NYR, October 24, 2002]. The main difficulty with this attitude is that it does not recognize that science itself is a human activity—whose aim is to answer our questions and whose content satisfies the human desire for understanding and explanation. We are necessarily separated from raw nature by our perceptual and cognitive limitations. The theories and even the “laws” we discover are not identical with nature. They serve our purposes. Thus, we do not know a priori whether digital or continuous variables are most useful in modeling certain phenomena or—as Wolfram challenges—whether the mathematical equations of traditional science will be successful in describing all systems of scientific interest. As in “human affairs,” the “truly fundamental” that Weinberg seeks may not always be simple.

Harvey Shepard

Professor of Physics

University of New Hampshire

Durham, New Hampshire

Steven Weinberg replies:

In his eloquent letter, Professor Shepard follows the lead of numerous postmodern philosophers and cultural critics by refusing to draw a distinction between the process and the product of scientific research. Certainly scientific research is a human activity, whose complexity gives the history of science much of its interest. And we can’t be sure that what we learn is uncolored by our human limitations. But we try to organize what we know about the world in theories that are as simple and objective as possible. Otherwise, what would be the point of it all?

The “credo” I expressed in my article is not limited to particle physicists like myself. In an 1861 letter to a friend, Charles Darwin remarked,

About thirty years ago there was much talk that geologists ought only to observe and not theorise; and I well remember some one saying that at this rate a man might as well go into a gravel pit and count the pebbles and describe the colours. How odd it is that anyone should not see that all observation must be for or against some view if it is to be of any service!

This is not the issue on which I disagree with Wolfram. He too seems to me to be searching for simplicity underlying the apparent complexity of nature. Nor do I claim to know a priori that the mathematical equations of traditional science will be successful in describing all systems of scientific interest. My point was that there is no reason to suppose that Wolfram’s automata represent a promising alternative.

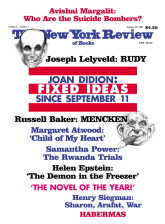

This Issue

January 16, 2003