“Up like a rocket, down like a stick”—thus, roughly, the multinational career of the Polish-American sculptor Elie Nadelman (1882–1946), whose present extensive exhibition at the Whitney Museum in New York projects, despite the jaunty flair and exquisite finish of many of its items, a shadow of melancholy. Nadelman was captivated by ideas, which inhibited and limited his work even as they inspired it. Born in Warsaw at a time when the Polish nation didn’t exist except as an idea, a language, and a fervent if wistful nationalism, and into an assimilated Jewish family whose one concession to their heritage was to name their youngest and seventh child Eliasz (Elijah), Elie Nadelman moved to Munich and then Paris in his early twenties, and to New York when he was thirty-two. He found the émigré artistic communities in these metropolises far from immune to the anti-Semitism that accompanied Polish nationalism; in later life he identified himself as a Pole rather than as a Jew, marrying a Catholic, Viola Spiess Flannery, in 1919, and raising their one child, a son, as a Christian.

In personality he was reticent, private, and formal; in a 1911 artistic credo he maintained, “The element that brings beauty in Plastic Art is logic, logic in the construction of form. All that is logical is beautiful, all that is illogical is inevitably ugly.” There is a hermetic quality to his statues, as if they have been sealed against infestations of illogical detail. In his later work, the layer of sealant gets thicker and thicker, and toward the end his figures, fingerless and all but faceless, seem wrapped in veils as thick as blankets.

Barbara Haskell’s catalog, in this day of ponderous catalogs composed like Dagwood sandwiches of disparate essays, has the rare virtue of being written by one person; with a brisk expertise she leads us through Nadelman’s early education and the artistic currents felt in fin-de-siècle Europe. Symbolism, the dreamy, semi-surreal countercurrent to naturalism, was felt to be expressive of the Polish soul as well as the individual inner life. Rodin’s contorted, vigorously thumbed forms dominated sculpture. Nadelman’s earliest three-dimensional works, three untitled plaster sculptures from 1903–1904 (lost but photographed for a Paris magazine), were Rodinesque in the extreme. But he had already received the aesthetic ideas of the Polish Stanisl/aw Witkiewicz, who wrote in 1891,

The value of a work of art does not depend on the real-life feelings contained in it or on the perfection achieved in copying the subject matter but is solely based upon the unity of a construction of pure formal elements.

In his six months spent in Munich, the young Nadelman encountered the rich trove of early classical Greek statuary in the Glyptothek, the decorative simplifications of German Jugendstil, and the theories of the Munich-based Adolf von Hildebrand, who in his 1892 book The Problem of Form in Painting and Sculpture proposed, much as Witkiewicz did, that, in Haskell’s paraphrase, “true art did not imitate nature…. Rather, art must obey its own internal structural laws in order to achieve its true content and immutable aim: formal unity…which was attainable only by means of distinct outlines, compact form, and smooth surfaces.”

In Paris Nadelman put these principles to work and in 1909, two years after Picasso had painted African masks into his large and discordant canvas Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, the Polish artist achieved a sensation with a show at the Galerie E. Druet, of thirteen plastic nudes and heads—life-size or smaller—evoking classic Greek models, plus one hundred radically formalized, rather attenuated drawings.1 Two years later, at London’s William B. Paterson Gallery, he exhibited ten female marble heads closely patterned after heads by Praxiteles; one viewer, the Polish cosmetics queen Helena Rubinstein, recognized in them a hymn to generalized beauty, and bought the entire show, as well as commissioning the artist to execute “a quartet of freestanding female figures engaged in the daily activities of bathing, combing their hair, and dressing.” Not yet thirty, the slender, wavy-haired, romantically handsome Pole was a success, an anti-Rodin offering the public an ideal of beauty harking back to the wellsprings of Western art.

Encountering these works nearly a century later is a mixed and somewhat frustrating experience. The bronze Suppliant (circa 1908–1909) greets us, arms lifted, hips invitingly tilted, as we step off the Whitney elevator. How could one not love her? True, her breasts seem a bit close together, and, though graceful from the front and back, she seems in the side view rather stiff and ungainly. Her supplicant gesture reaches for the timeless; unlike a nude by another anti-Rodin sculptor, Aristide Maillol, she does not make us think of the flesh-and-blood model who posed for this rendering. From the same 1908–1909 time frame, Nadelman’s smaller pearwood Standing Female Nude, with her tiny head and rubbery limbs, strikes the note of caricature that will flavor much of his best work; her sinuous, even agitated lines remind us that young Nadelman had opportunity to study the vivacious altarpieces of Germanic limewood sculptors like Veit Stoss (in Kraków) and Tilman Riemenschneider (in Munich). The bronze of a hefty, hunched nude alleged to be Gertrude Stein makes us smile, but her Junoesque mass is something that Nadelman will work his way back toward through the coming decades of distinct outlines and smooth surfaces.

Advertisement

His marble heads, of which more than Helena Rubinstein’s ten are displayed, confront us with a deliberate polished blankness. As in the drawings of Nadelman’s fellow Pole Bruno Schulz, the faces are downcast, the foreheads leading. When we stoop down and seek to look them in the eye, the eyes are not only pupil-less but, often, blurred as if blind. If, as I was told in a fine-arts class fifty years ago, the stone faces of medieval statues have an inner life not found in those of classical Greece, Nadelman’s managed to have even less inner life than their Greek prototypes. Rather desperately we rove from one to the other, hoping to penetrate their marmoreal opacity; some have noses a little broader than others, and some of the stylized, hat-like headdresses differ in detail, and the marble in which they have been carved varies in tint from bluish to brownish, but all have been sacrificed on the same high altar of impersonality, like so many heads severed in the cause of revolution. There is a soapy coldness to them, faintly interrupted by the Ideal Head of a Woman owned by the Mount Holyoke College Art Museum, whose big chin and dished face hints at individuality, as if a real woman momentarily distracted Nadelman from his quest for ideal beauty.

Beauty lives, surely, in a harmonious excitement of particulars. The spark of life comes in individual vessels. In some slightly later heads—the bronze from the Philadelphia Museum of Art (circa 1912–1913), and one of wood from the Whitney’s own collection (circa 1912–1913)—have a Modigliani-esque edginess, a hint of incipient motion, an impudent caricatural shrinkage of lips and the space of the upper lip, which animate them. Also highly animated are the five bronze nudes circa 1912–1913: the male, from a private collection, carries the restless mannerist line into a fine swagger, and the female nude from the Museum of Modern Art almost explodes into dance. This is the kind of visual jazz that Nadelman’s instincts called for but his formal puritanism kept repressing. The beat continues in the two draped, bare-breasted figures of the same years, one in bronze and one carved (circa 1915) from cherrywood; they are identical except for their medium, and the bronze surface is the one where the highlights swim and flow.

Nadelman was a tireless experimenter in materials; his method generally began with plaster models and could branch into wood, marble, or bronze in various patinas. The nudes mentioned above were done in a dark, almost black, bronze, while the Metropolitan Museum’s Standing Nude (originally Juggler, circa 1912) is painted with gilt, and the Two Standing Nudes (circa 1912)—a reserved but charming and lively work, one of his first linked duos—are golden-tinged gilt bronze. Like Brancusi, he manipulated a fi-nite number of motifs, varying the material and the size, though something authentically primitive in Brancusi avoided any impression of mass production or of seeking a serial approach to Platonic ideality.

Nadelman’s rocket was still ascending as World War I approached; his neomannerist pieces sold, and Guillaume Apollinaire in 1914 praised his early attempts to blend classical forms with contemporary clothing. The venture into such costume came about by way of the god Mercury’s brimmed helmet, which looked like a bowler hat (Mercury Petassos I and II, circa 1914) and led to the top hat of Le boulevardier (1914). Nadelman’s initial reaction to the guns of August was to want to travel through Germany and report for duty as a reservist in the Russian army; the authorities advised against so hazardous an enlistment, and Helena Rubinstein concocted a commission for him to create a plaster relief for her newly opening salon in New York. He left on the Lusitania, expecting to stay in America a few months. He stayed for the rest of his life.

Though the United States struck him as “a country of bluffers and snobs and…still quite wild,” some of his most elegant and memorable sculptures date from his first years here: Man in the Open Air (circa 1915), insouciantly posed by a minimal tree, clad in no more than a bowler hat and a wire bow tie; the terrific larger black bronze Horse of 1914, a broad-chested, slim-legged, crop-tailed essence of equineness; the four taut and fine-boned figures of deer of 1916–1917, Standing Buck warily alert, Fawn and Resting Stag peaceably licking their feet, and, most dramatically, Wounded Stag, with its golden patina, bent back in agony, compactly contorted like a Celtic clasp. Such enlivening touches verge, for Nadelman, on the vulgar, or on rivalry with the American master of bronze animals, Paul Manship. A startling experiment, not repeated, mingles white marble and dark bronze in Sur la plage (1916–1917), a kitschy flirtation with the anecdotal. Nadelman still produced ideal heads, more Renaissance now than classical in feeling, and misty if not somnolent in expression, with headdresses like handles, and the marble so polished as to ape porcelain.

Advertisement

His marriage to the wealthy Mrs. Flannery opened to him a field of society portraits and, though not among Nadelman’s tickets to the annals of modernism, these portrait busts and heads gave value to their sitters: real likeness contends with Nadelman’s softening style. Francis P. Garvan Jr. and his sister Patricia (both circa 1920) emerge as eerie but actual children; the little girl Marie is darling in her pudgy contours; and the several classy adult females outface the half-melted look he gives them. Yet, while still enjoying social and critical esteem, Nadelman was about to take an enduring blow: he had developed a series of painted plaster figures drawn from the life around him, and it met with a surprisingly hostile reception. Most of these works survive only as photographs; Femme assise (1917), displayed as part of a war-relief benefit on the roof garden of the Ritz-Carlton Hotel, was knocked from its pedestal and shattered. It and his two other plaster pieces in the show were ridiculed in the press. Haskell reports, “In a satirical feature article they were singled out, along with work of Brancusi and Henri Matisse, as avatars of modern art’s preposterous incomprehensibility.”

So anti-modernism had caught up with the conservative Nadelman, and, though clothed and painted statues had a venerable artistic pedigree, he could never sell his. At a 1919 one-man show at M. Knoedler & Company, the plaster works went unbought and the option of ordering wooden or bronze duplicates went untaken. A 1925 show at Scott & Fowles of bronze and stained, gessoed, and painted wood figures sold a single piece, High Kicker (circa 1920–1924), and that one to Stevenson Scott, a partner in the gallery. The pieces were withdrawn to the basement and attic of the Nadelmans’ big Riverdale house, where they may have suffered dampness and damage.

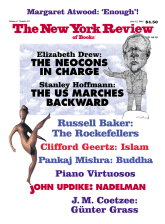

Seeing many of these spurned works at the Whitney, one wonders how such wit and sculptural élan could have been so thoroughly missed. Hostess, for example, comes right at you with social momentum, her white face turned as if to spot a new guest; Host is all heavily seated pomp; Tango (see the illustration on page 16), used for the catalog’s cover, has an apprehensive grace made haunting by the figures’ abraded faces and failure to touch hands; Woman at the Piano is iconic, an American maenad with her flailing hands and transfixed sideways stare, her feet up on their heels to press the invisible pedals. The bare-legged circus girls, the white-tied conductor, and a row of high-kicking dancers seem to pause and gyrate like figures on a music box.

The art public, accustomed to investing in enduring materials like marble and bronze, hung back from sculptures so modest in size (rarely more than three feet high) and means, their impermanence and fragility manifest in their flitting gestures, their scabbed and rubbed surfaces. Critics, according to the catalog, have revived Nadelman because the rough treatment in his later work anticipates Abstract Expressionism; early Pop Art better fits the case, as in the wooden sculptures of Marisol and the junky combines of Rauschenberg and Johns. The Nadelmans in their financial heyday collected folk art with an omnivorous zeal, on the theory that the formal basis of all art would emerge from a sufficient accumulation. In the meantime, Nadelman’s shapely sculptures bore an uncomfortable resemblance to the battered dolls to be found on flea-market tables.

His financial fortunes followed his artistic. The Nadelmans’ wealth was hit so hard by the Depression they had to sell their folk art and some of their real estate. Then the war came, bringing Nadelman sympathetic pains for the fate of Poland and its Jews, though he avoided specifically Jewish causes. He joined the war effort as best he could, serving as an air warden and volunteering to teach sculpture and drawing in the occupational therapy division of the Bronx Veterans Hospital. He tried to ignore a heart condition, calling it “my amusing pain,” but failing health drove him to take his own life in the last days of 1946. Within a week Lincoln Kirstein, art critic and general director of the New York City Ballet, who had never met Nadelman, began a twenty-five-year campaign of study, preservation, and promotion of the nearly forgotten artist.

During the Depression and the war Nadelman had become reclusive, refusing the few invitations to exhibit that came his way, dropping out of his posh clubs, and trying to hang on in Riverdale. His experiments with plaster continued, however; from 1925 to 1927 he worked on what he called “galvano-plastiques”—large electroplated plaster figures, ten of which were exhibited in 1927 at M. Knoedler. They failed to sell at the bargain price of one thousand dollars each. Next, he took to laminating large hollow-core plaster shapes with brownish papier-mâché, giving them the warm, clumsy look of terra cotta. In the early Thirties he did small ceramic figures, often pairs of women, with scanty, festive costumes painted on. Lastly, from 1938 to his death, he devoted himself to very small plaster figures, multiply cast in molds and then worked over with a file, fork, or penknife. Inches long, unable to stand on their own, reminiscent of prehistoric fertility charms, these figurines, forty or so of which are collected in the exhibit’s last room, radiate the fitful unease of a man at the end of his tether amusing himself, an obsessed hobbyist gouging away at problems only he can discern.

But the larger works, the galvano-plastiques and papier-mâché giants, called “circus women” but more like lounging goddesses, have an air of arrival, of self-careless triumph. They are fat, by a sculptor whose slender, nervously dwindling legs amounted to a signature. They are the culmination of Nadelman’s drive toward the undefined, the blurred, the featureless generic. They suggest George Segal’s white body-casts, Botero’s unembarrassed tubs, and Nikki de St. Phalle’s jubilantly bulbous women. Not that these figures of Nadelman’s are jubilant; they are eyeless, groping in a kind of dark. But they have a monumentality not present in his work before, and the papier-mâché women are grander and vaguer still.2 Two foot-high marble statues called Standing Nude (circa 1930–1935) achieve the same formlessness, weirder in marble than in ceramic. The impulse behind such blobbiness, such reverse refinement, like that behind the monotonous repetition of pseudo-classical heads, baffles and mocks a critic’s expectations of—what?—of declaration, of thereness. As the stick of his rocket descended, Nadelman’s figures seem to sink back into the all-dissolving waters of being. Perhaps, having early turned against the amorphous ethos of Symbolism—Munch’s swooning women, Moreau’s luminous nebulae of impasto—the sculptor yearned to revert to it, an inner world devoid of formal logic.

This Issue

June 12, 2003

-

1

Nadelman placed a high value on these drawings. Writing for an exhibit in 1923, he claimed, “These drawings, made sixteen years ago, have completely revolutionized the art of our time. They introduced into painting and sculpture abstract form, until then wholly lacking. Cubism was only an imitation of the abstract forms of these drawings and did not attain their plastic significance.” Two years later, he asserted, “Picasso is not the originator of Abstract Form, he merely exaggerated the abstract forms discovered by me, and not knowing their workings, piled up pell-mell abstract forms… with a result which is meaningless and unsignificant from the point of view of plastic art and is merely a sensational novelty.”

↩ -

2

Two Circus Women, which measures about five feet tall, was, with Kirstein’s approval, posthumously cast in bronze for Nelson Rockefeller, and then subjected to a three-fold enlargement in marble for the New York State Theater at Lincoln Center. This rendition, though a spectacular homage, is at considerable variance with Nadelman’s usual scale, and with the peculiar warmth, the delicate earthiness, of the papier-mâché-over-plaster original.

↩