1.

David Garland’s disturbing new book addresses the question why there are so many more people in jail in America and Britain than anywhere else. That, in any case, is its specific focus. Its broader concern is with “cultures of control,” how societies treat deviance and violence and whom they single out for what treatment. He deals with this politically sensitive subject less dramatically than Michel Foucault did in Discipline and Punish, which brought the subject into public debate in the 1970s.1 Garland brings a larger amount of factual information to bear, but Foucault’s influence shows in his account.

His argument is that by 1980, both countries established a new system of crime control, a system based almost exclusively on imprisonment. This system has continued unabated ever since, the current decade being the most punitive in US history. The new approach to managing crime, in Garland’s account, was an expression of the triumph of free-market political conservatism over the protest-generating upheavals of the late 1960s and 1970s. What finally emerged in both countries was a highly efficient and technically controlled system of crime management directed almost exclusively at protecting crime’s potential victims instead of coping with its causes. Its principal instruments, inevitably, were swift arrest, tough sentencing, and extensive incarceration. Penal welfare and rehabilitation got lost in the process. Moreover, the transformation took place with scarcely a murmur of public protest. It seemed to escape attention, except among those it affected personally.

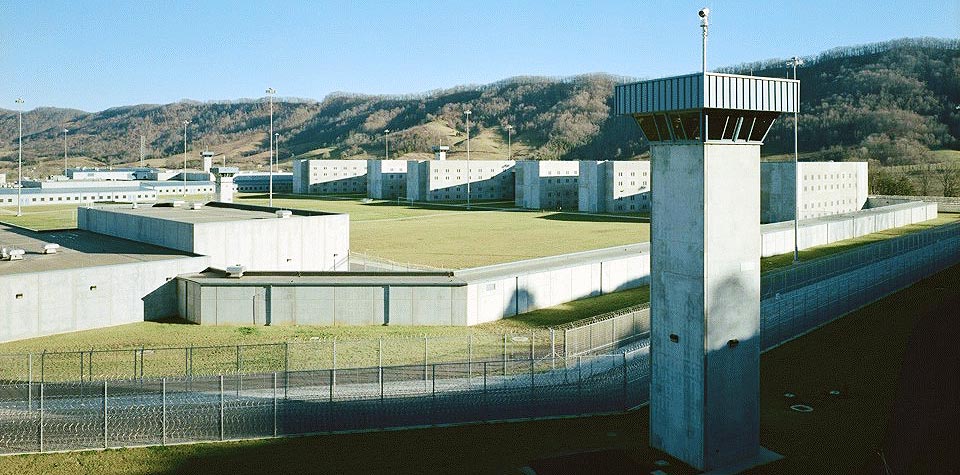

Here are some facts about skyrocketing imprisonment. There are approximately two million people in jail in America today, 2,166,260 at last count: more than four times as many people as thirty years ago.2 It is the largest number in our history. More than 500 in every 100,000 Americans are behind bars, between four and ten times the incarceration rate of any civilized country in the world. In Britain, the country with the second-steepest rise in the rate of imprisonment, the number of prisoners has climbed from about 70 per 100,000 in 1966 to 136 per 100,000 in 1998. Italy, by comparison, had 57 per 100,000 in jail in 1990, down from 79 in 1960, while Japan had halved its imprisonment rate over those same years from 66 to 32. And our incarceration practices are becoming well known, if not notorious, abroad. As witness a recent feature article in The Irish Times of Dublin (August 8, 2003): “Applying the US incarceration rate to Ireland would result in 27,500 people behind bars instead of 3,200 as at present.”

But gross numbers are only part of the story. The other part is racial imbalance. Twelve percent of African-American men between twenty and thirty-four are currently behind bars (the highest figure ever recorded by the Justice Department) compared to 1.6 percent of white men of comparable ages. And according to the same source, 28 percent of black men will be sent to jail in their lifetime.

What has caused this drastic rise in imprisonment? Is it an increase in crime, as one might assume? This explanation doesn’t adequately fit the facts. Something else has been going on as well. For crime rates in America, after rising sharply through the 1960s into the early 1970s, began leveling off in 1972 and stayed level for the two decades following—nobody quite knows why. It was not until crime rates had already leveled off that incarceration rates began their steady, year-by-year climb. Between 1972 and 1992, while the population of America’s prisons grew and grew, the crime rate as a whole continued at the same level, unchanged.

The incidence of violent crimes during that tell-tale period is revealing. The homicide rate in the US remained steady at around 10 per 100,000 from 1972 to 1992, in spite of the four-fold increase in incarceration (from about 100 to 400 per 100,000), while the rates of robbery, rape, and aggravated assault actually went up by more than 50 percent.3 One might say, of course, that quadrupling the imprisonment rate was part of a largely failed effort to reduce the steady rate of crime, especially the violent crimes about which we’re most concerned. But twenty years of steadily increasing imprisonment with, at best, few results? It should also be remarked, by the way, that there has never been much substantial evidence that raising imprisonment rates reduces crime.

Starting around 1992 violent crime in America began declining and it is still going down—again, nobody is quite sure why. The homicide rate, for example, dropped from its two-decades-long 10 per 100,000 in 1992 to 6 per 100,000 in 2000. But despite that decline in violent crime over those years, the number of people in jail continued to rise steadily: from some 350 in 1992 to nearly 500 per 100,000 at the end of the millennium—an increment that adds up to tens of millions more days in prison.

Can we conclude, then, that the dramatic increase in imprisonment that began in 1972 belatedly began deterring violent crime in 1992, twenty years later, when crime rates started dropping?4 If this is the case, then why did the rate of imprisonment continue to increase after crime had begun declining?

Advertisement

Crime continues to be on the decline. Yet incarceration rates are still increasing, though they have begun leveling off, even declining slightly, in a few states, more as an economic measure than as one of changed attitudes toward the harshness of prison policies. Even so, the weekly increase in the number of jail beds needed between June 2000 and June 2001, for example, was 587: not as great as the 1,500 weekly increase in the 1990s, but still considerable. Why are there 30,000 additional jail beds per year while crime continues to decline?

2.

The new culture of control that emerged in the 1970s has turned out to produce even more racially imbalanced imprisonment than before. And it is particularly striking in those states with a prior history of lynching,5 as with Louisiana, for example, with 794 per 100,000 in prison, compared with Maine’s 141. Today, as already noted, three in ten black men between the ages of eighteen and thirty-five will have served time in jail or under criminal supervision in their lifetime. Our jails are full of poor, young blacks. Latino immigrants and their American-born children are second on the list, though well below the figure for blacks. Our policy has led a French critic, Loïc Wacquant, to ask whether America deals with its problems of poverty and race by building new jails rather than urban housing.6 And, indeed, huge imprisonment costs do siphon money away from more indirect forms of crime control, like New York City’s federally funded Ten-Year Plan for better housing and more available homeownership. During the decades of our recent jailing spree, for example, federal funds available for the Ten-Year Plan have dropped from $55 billion in 1980 to less than $15 billion today,7 while funding for prison construction and maintenance continue to grow.

Crime, to be sure, has always been associated with poverty and race in the Anglo-American world and elsewhere. But is our new system of crime management amplifying this phenomenon? Have we come to take “minority” crime (and perhaps crime generally) as inevitable and irremediable so that we just accept draconian “crime management” as its only remedy, much as we accept the Fed’s raising interest rates to control inflation? And have we accepted, as well, the “inevitability” of our racial imbalance in imprisonment? Are we simply refusing to acknowledge, whether out of guilt or indifference, the social consequences of locking away two million Americans in our jails, more than three quarters of them African-American?

Recall the mild and brief outcry in 1994 when California began spending more on its prisons than on its state universities. That pattern has continued since then. California’s jailing costs have grown steadily from $200 million in 1975 to $4.8 billion in 2000—now estimated at $21,400 annually per prisoner.8 California has at least taken some steps to cut these staggering costs. In a recent referendum, voters in California enacted a new state law requiring treatment rather than prison time for nonviolent drug crimes. But even so, California still has the largest prison system in the country, with 162,317 men and women behind bars in 2002.

To cut down its still overwhelming costs further, California, like other states, has taken to privatizing its prisons. The result is that incarceration is turning into a competitive and profitable industry. In the last fifteen years, some half-dozen “security firms” have come into well-financed existence. They now lock up about 150,000 of our two million prison inmates—more than the entire population of France’s jails. Middle-sized towns in search of jobs for their citizens now compete for new prisons and offer well-situated local sites at reduced prices. Commercial prisons boast of their lack of amenities, which amounts to drastically reduced rehabilitation and probation services.

And what about the prisoners who are increasingly crowded into our jails? Who are they? Henry Ruth and Kevin Reitz, in their new The Challenge of Crime, give this account:

From the early 1970s to the mid-1980s, the US prisons expanded because the courts were sending more “marginal” felons to prison than they had in the past. Many burglars or auto thieves who might have been put on probation in the 1950s or 1960s were instead sentenced to incarceration…. Then, from the mid-1980s to the early 1990s, prison growth was driven most forcefully by the war on drugs…. In the 1990s, the primary cause of prison growth changed again. For the first time in the expansionist era, the chief engine of the prison build-up became longer sentences rather than more prison admissions.9

As one might suspect from these figures, a very small part of this increase in imprisonment has had any impact on violent crime. Indeed, as one well-known study has shown, California’s tripling of its jail population in the 1980s affected the rate of violent crime insubstantially if at all.10 Breaking state figures down crime by crime, some 3.9 crimes per year are believed to have been prevented by each year of imprisonment per person, of which 3.25 (90 percent) are nonviolent burglaries and larcenies. Only 0.007 homicides and 0.055 rapes were prevented per prisoner-year.

Advertisement

3.

How did America (and Britain to a lesser degree) come to embrace the new style of crime management? The culture of control of these past three decades surely was not unprecedented, however much its efficiency may be brand new. As Garland writes, it is the reemergence of an older “just-desserts” ideology of retribution, reinforced by a deep-seated if well-concealed racial bias. The new lockup approach simply takes the appropriateness of retribution for granted, without considering whether it is morally justified. Protecting the public (rather than reducing crime) is “business.”

This approach, moreover, depersonalized crime management by making it increasingly technological—as with the NYPD’s fabled COMSTAT, the computerized network for keeping current the flow of crime information, even (or especially) on the policeman’s beat. And depersonalization fits the efficient ideology of new, conservative theories of crime control, well exemplified by James Q. Wilson’s enormously influential Thinking About Crime.11 Politicians and legislators, sensing the change in social mood, were quick to accommodate it by passing tougher criminal laws.

But there is a longer history as well. Locking people up for extended periods is almost exclusive to the more developed, urbanized world. While its object has always been to punish, imprisonment also takes for granted that jailing criminals dissuades them from committing further crimes later on. And jailing obviously keeps criminals from preying on the rest of us. It was not until the late nineteenth century that liberal prison reform—ideas like rehabilitation and “reformatories”—was widely put into effect. The story of these changes is well told in Michel Foucault’s celebrated book.

The new reforms grew fast. By 1950, as Garland notes, prison welfare had become a standard feature of penal practice. Through flexible sentencing, supervised parole, treatment for drug dependency, psychological counseling, and job training, the prisoners, so it was intended, were to leave behind a life of crime and reenter everyday society. So well accepted had prison welfare become by mid-century that its quick undoing still surprises some penologists.

The first angry explosion of doubt about the entire system of prison welfare came at the end of the 1960s when crime was still rising. It was, ironically, set off by a 1971 report issued by a study group of the American Friends Service Committee, Struggle for Justice. The report lashed out at the criminal justice system’s unbounded power to repress blacks, the poor, and the young, not only through imprisonment but through “paternalistic” practices of “individual” rehabilitation. Society, not individuals, needed rehabilitating. Bitter debate followed. There ensued what Garland calls the “nothing works” era. Everything in the criminal justice system was scorned, reviled. Academic criminology even accused itself of having fallen prey to a hegemonic system for victimizing the poor, the weak, minorities.

This bitter wave of attacks from the “liberal” side, Garland believes, had an odd but not altogether surprising effect on the law enforcement establishment. It discouraged prison reform and gave support to the belief, expressed up to that time by only the most skeptical and conservative scholars and politicians, that the only way to deal with crime was by keeping criminals safely behind bars. By the mid-1970s, indeed, law enforcement authorities in both the US and Britain were beginning to conclude (however reluctantly at first) that high crime rates were here to stay. In Garland’s words,

The last quarter of the twentieth century saw the emergence of non-correctionalist rationales for crime control—new criminologies, new philosophies of punishment, new penological aims, and objectives. Over the same period there was also an attempt on the part of politicians and others to improve the fit between crime policy and the new political and cultural context in which it operates—to invent new and more effective mechanisms of crime control as well as new ways of representing crime and justice.

Stop crime in its tracks, get it off the streets, keep it behind bars. Probation, treatment, and rehabilitation were largely abandoned.

Ways of fighting crime can, of course, be as irrational as crime itself. They’re rarely subjected to public debate, except when a disaster such as the uprising at Attica Prison in 1971 forces them into the open. In neither Britain nor America has there ever been a well-reasoned, official statement of imprisonment policy. Indeed, a British White Paper in 1964, The War Against Crime, while acknowledging the rising crime rate at the time, made no explicit statement about imprisonment policy and expressed full confidence in the traditional system then in force. In America, in any case, imprisonment policy (varying widely from state to state, as we’ve seen) would be impossible to formulate consistently.

Without a national policy for punishing and coping with crime, “local demands” take over and almost invariably ignore long-range consequences, such as racial imbalances in imprisonment and what their effects may be. Three quarters of those in jail in America are black, and yet we don’t seem to realize, or at least care, how these numbers might cause the black population generally to feel alienated from American society. Nor do we seem concerned whether a system that seems obsessed with punishment and retribution, and that virtually ignores the awful conditions in prisons, might intensify this alienation. With two million Americans locked away, hundreds of thousands of them, many of whom have forever lost the right to vote, return to civil society each year to tell their often embittered stories. Ought not such matters concern us?

There are some signs, perhaps, that this dismal and embittering state of neglect and indifference in our overcrowded prisons is beginning to get some public attention—even if it takes shock treatment to wake us up. The recent brutal murder in a Massachusetts Correctional Center by a homophobic fellow inmate of the ex-priest child molester John Geoghan made plain how far our system of incarceration has given up on the ideal of rehabilitation. As an editorial in The New York Times (August 26) put it, the “violent death was eminently preventable…. If elected officials insist on sending so many people to prison, they must be willing to pay the bill for maintaining minimum safe and decent standards.” Up to now, alas, they have not been willing to provide even adequate prison medical care, as a disturbing article in the August 2003 Harper’s magazine reports.

Garland’s more detailed diagnosis of the present state of things is revealing. He quotes Raymond Aron on great social transformations, that they are “born of general causes [and] completed as it were, by accidents.” What, then, in Garland’s view, are the general causes and accidents in this pe-riod of wholesale jailing? He sees the quarter-century from 1950 to 1973 as an “unfolding dynamic of capitalist production and exchange” with its “ethos of consumption and consumerism” during “three decades of uninterrupted expansion and prosperity,” when “monopoly capitalism reinvented itself as consumer capitalism.”

But by the mid-1970s, a change began setting in:

While the best-qualified strata of the work force could command high salaries,…at the bottom of the market were masses of low-skilled, poorly educated, jobless people,…a large part of them young, urban, and minority… with continuous unemployment a long-term prospect.

Britain suffered the decline a bit sooner than America did, but we quickly caught up. Our uneven distribution of wealth can match any in the civilized world. That was one element of destabilization.

Family life changed at the same time. In Britain, for example, the ratio of divorces to weddings shifted from 1 to 58 in 1938 to 1 to 1.22 in the mid-1980s. By the 1990s, a third of American children were born to single mothers, nearly three quarters of them African-American. Household size shrank in the UK from 3.4 people to 2.7 in the last half of the century. Urban renewal had the inadvertent effect, particularly in the 1950s and 1960s, of destroying established neighborhoods in both countries, replacing them with high-density, violence-breeding housing projects. And there was unprecedented “white flight” to the suburbs, leaving Chicago, Los Angeles, Newark (or the “sink estates” in Britain) with unmanageable black ghettoes.

Not surprisingly, welfare grew beyond anything envisaged in Britain’s Beveridge Report of 1942 or in American forecasts, and with it middle-class discontent with a rising tax burden. A new middle-class bitterness was developing. These were the years, between the mid-1950s and early 1970s, when the crime rate soared. Crime, Garland believes, was also indirectly encouraged by opportunity. The middle class developed more extravagant consumer habits, and opportunities for theft increased as the amount of portable high-value goods increased. Robberies rose with the growing number of well-stocked, day-long deserted middle-class homes. And with a steady increase in unsupervised baby-boom teenage boys, their parents away at work, criminals had no lack of young recruits. Add to all this the beginning of drug abuse, and crime was almost bound to rise in the troubled 1950s and 1960s.

During the same period, of course, came the rise in anti-authoritarian sentiment among the young—the Paris uprising, the Red Brigades, sit-ins, the New Left. Whether it encouraged crime is difficult to know. But it did make law enforcement authorities warier and more distrustful and more defensive. With welfare costs, taxes, immigration, and disorder rising in both Britain and America by the 1960s, conservative politics began having more appeal.

Crime had in fact been rising steadily from the mid-1950s; now it had become an issue of intense political concern, if not obsession. And it was in 1972 that incarceration rates started rising, and kept rising for three decades, through the Reagan/Thatcher era and beyond.

Fortunately, crime continues to decline, though the US incarceration rate continues to rise (by 2.6 percent last year, the largest increase since 1999). As a nation, we could eventually be more deeply injured socially by mass imprisonment than by moderate crime. For imprisonment amplifies the alienation that so often fuels crime, particularly when imprisonment is so racially imbalanced.

I mentioned earlier the deplorable epidemic of lynching in the South in the 1890s and in the three decades following (the subject of the book David Garland is currently working on). Has imprisonment now become the covert but official method of dealing with “disorderly” blacks in America, with capital punishment its extreme expression? Is “indifference” to the huge imbalance of blacks in our prisons less an expression of “indifference” than of denial, of wanting to turn away from the problems of race in America? After all, the Supreme Court affirmed the principle of integration in Brown v. Board of Education in 1954: it’s up to “them” now. To paraphrase Loïc Wacquant’s remark, mentioned earlier, yes, we build prisons to provide housing for the black poor. And yes, of course, we have come to accept better-educated blacks who have made it. Prison is for the blacks who haven’t. Is this progress?

David Garland has done us a great (if distressing) service with his important book. The time is surely long overdue for a fresh look at what he calls the culture of control, and how it can make more trouble for us than it cures.

This Issue

September 25, 2003

-

1

Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison (Pantheon, 1978).

↩ -

2

This is the figure given by Fox Butterfield, “Study Finds 2.6% Increase in US Prison Population,” The New York Times, July 28, 2003.

↩ -

3

Nonviolent property crimes fell during this period. As Henry Ruth and Kevin R. Reitz write in their new book, The Challenge of Crime: Rethinking Our Response (Harvard University Press, 2003, p. 101), “From 1973 to 2000, a quadrupling of US incarceration rates corresponded with a 71 percent reduction in burglary and a 65 percent reduction in theft, with these declines accumulating fairly steadily over the entire period.”

↩ -

4

In The Challenge of Crime, Ruth and Reitz deal particularly with the issue of whether incarceration has had any effect on crime.

↩ -

5

Lynching in the South flourished from 1890 through the first quarter of this century. It ended when it was made a federal offense in 1936, with conspiring local officials held liable as well as the citizens to whom they handed over suspected black criminals.

↩ -

6

See Loïc Wacquant, Prisons of Poverty (University of Minnesota Press, 2001). A broader picture can be found in Mass Imprisonment: Social Causes and Consequences, edited by David Garland (London: Sage, 2001).

↩ -

7

See Ingrid Ellen, Michael Schill, Amy Schwartz, and Ioan Voicu, “The Role of Cities in Providing Housing Assistance: A New York Perspective,” a working paper presented at the NYU Law Faculty Workshop, November 12, 2001.

↩ -

8

In December 2002, California Governor Gray Davis proposed severe cuts in his midyear budget proposal, sharply reducing public welfare payments for dental care, for subsidized child care for welfare recipients, and even reducing state funding for state highway construction. But the budget of the Department of Correction, which runs California’s prisons, was virtually untouched. According to the Sacramento Bee, “Davis said he would not balance the budget by jeopardizing public safety.”

↩ -

9

Ruth and Reitz, The Challenge of Crime, pp. 95–96.

↩ -

10

Franklin E. Zimring and Gordon Hawkins, Incapacitation: Penal Confinement and the Restraint of Crime (Oxford University Press, 1995).

↩ -

11

Basic Books, 1983.

↩