Between 1907 and 1908 the French publisher Plon brought out, under the title Récits d’une tante (Tales of an Aunt), the four volumes of the Memoirs of Adèle, Comtesse de Boigne; and a very remarkable book it is, with a remarkable subject. The comtesse, née Osmond, was born in 1781, the daughter of the Marquis d’Osmond, a descendant of an ancient Norman family, and of Eléonore Dillon, offspring of an influential Irish clan with Jacobite connections.1 One of Adèle’s great-uncles had been a popular figure in the Palais Royal circle,2 and through this connection and with the help of other Dillon relatives her mother secured the post of lady-in-waiting to Madame Adélaïde (1732–1800), one of Louis XV’s daughters.

This position entailed living at Versailles, which suited Adèle’s haughty mother ideally, though her father, an unassuming man, rather less so. However, in 1787, he left the army for the diplomatic service, being appointed minister to The Hague and then ambassador to St. Petersburg. He was an enduring, though never fanatical, royalist and legitimist, and Adèle idolized him.

As for Adèle herself, she was a pretty and precocious child, able to recite Racine at the age of three. Both her parents, so she says, adored her, and she became a favorite with Louis XVI and Queen Marie-Antoinette. “I was,” she writes, “brought up literally upon the knees of the royal family.”

In her chapters on her childhood days she gives a most touching picture of the desperate social awkwardness of the unfortunate King:

With the best intention of being courteous, he would walk toward a man until he had pushed him back to the wall; and if no remark occurred to him, as often happened, he would burst into a loud laugh, turn on his heel and walk off.

The victim would take his leave in fury, believing himself deliberately insulted.

Then in 1789 came the Revolution. Adèle’s father (there was now no question of his mission to Russia) helped Madame Adélaïde and her sister Victoire to escape to Italy and sent Adèle with her mother and brother to follow them, staying on in France for some months himself, to give what support he could to the King and Queen. The family was reunited in Rome, where they encountered a certain Sir John Legard, whose wife was a first cousin of Adèle’s mother. By now their money was running low, and they accepted an invitation from Sir John to accompany him to Naples and ultimately to take refuge on his estate in Yorkshire.

The talk of the town in Naples, at this moment, was the famous Lady Hamilton, wife of the English minister and later the lover of Horatio Nelson. Adèle has several irresistible pages about her: she had a unique talent, with the aid of a classical costume, some cashmere shawls, an urn, a scent-box, a lyre, and a tambourine, for what were known as “attitudes,” emerging eventually from her shawls as “a statue of most admirable design.”

Adèle sometimes acted with her as a subordinate figure. Once she placed Adèle on her knees before an urn, with hands clasped as in prayer, but suddenly grasped her by the hair,

with a movement so sudden that I turned round in surprise…which brought me precisely into the spirit of my part, for she was brandishing a dagger. There were cries of “Brava, Medea!” Then drawing me to her and clasping me to her breast as though she were fighting to preserve me from the anger of Heaven, she evoked loud cries of “Viva, la Niobe!”

During their ten months in Naples the Osmonds were taken up by the Queen, and the young Adèle began a long-lasting friendship with the Queen’s daughter, the Princess Marie-Amélie, who in 1830, as spouse of Louis-Philippe, was to become queen of the French.

Their stay in Yorkshire, which lasted a year or so, gave Adèle a vision, to the point of caricature, of the old English squire, whose nightly toast was “Old England for ever, the King and constitution, and our glorious revolution.” During this time Adèle’s father made her study eight hours a day, though, she records unresentfully, he allowed her to read only under his supervision. (“He would have been afraid to see false ideas growing in my young brain, if his wise reflections had not checked their development.”) She developed a taste for political economy, and, a little later, it made Calonne, the sometime French controller-general of finance, laugh to find her reading Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations. “This was my first intimation that such tastes were not usual in girls of fifteen.”

Her mother’s health was not good, and in 1795 they moved to London to be within easy reach of doctors. Her father took a three-year lease on a little house in Brompton. It was an action, writes Adèle, that would have injured his reputation with his fellow émigrés, who, in their madness, thought it more befitting to take lodgings for no longer than the week—so imminent was the counterrevolution.

Advertisement

Despite their lack of funds, the Osmonds kept open house on Sundays for a musical matinée, attracting a fashionable crowd. Adèle, who had a fine singing voice, figured prominently in these concerts; and in due course one of the regular attendants invited her mother to dinner and, the next day, sent a friend, Mr. O’Connell, to Adèle’s father to request her hand. The lover was General de Boigne, a very distinguished military man who, for twenty years, had served as commander in chief to the Mahratta prince Sindiah. He was by now forty-nine, lean, tall, and formidable, still vigorous though malarial, and, from his spoils in India, exceedingly rich.

Adèle was prompted to make what she later called a “grave, though generous, mistake.” She asked for twenty-four hours to consider the proposal and employed them to invite herself to the O’Connells to discuss things face-to-face with Boigne. She told him frankly that she did not care for him in the very least and thought it unlikely that she ever should, but if he would secure her parents’ independence she would be very happy to marry him. She named the figure, not only of her dowry but of a very substantial allowance to her parents and also one to her brother. But further, if Boigne’s biographer Henry Bordeaux is to be believed, she discussed with him the awkward fact that Boigne had brought back from India a Persian wife and two children, whom he had settled in comfortable style in Enfield, and they agreed that, though he would repudiate this earlier marriage as not valid under English law, Adèle should bring the children up as her own.3 Her terms were agreed on, and they were married twelve days later, with a prince of the blood, her uncle the Bishop of Comminges, and several other social luminaries in attendance.

Adèle’s Memoirs say nothing of the bargain about the children, and her own biographer, Françoise Wagener, wishes us to believe that she did not know about the earlier marriage until much later, when it came as a shattering surprise.4 At all events, the marriage was a disaster, and a long-running one—though after they agreed to separate in 1812 they began to see virtues in each other.

Adèle’s marriage is a rich subject, but impossible to explore here. I will content myself with two pieces of suggestive evidence. Adèle writes:

He [Boigne] was endowed with the most disagreeable character that Providence ever granted to man. He wished to arouse dislike as others wished to please. He was anxious to make everyone feel the domination of his great wealth, and he thought that the only mode of making an impression was to hurt the feelings of other people.

By contrast, the Baron Thiébault writes in his memoirs that

Madame Osmond and her daughter persecuted him [Boigne] to the point that he was obliged first to desert the conjugal home and then Paris, where he had hoped to live …and to take refuge in Savoy, his native land…. He could not make the slightest movement but these ladies mortified him in the cruellest manner. Did he cough? “But, monsieur de Boigne, no one coughs like that in good company.” Did he blow his nose?… “But, monsieur de Boigne, this is shocking.”5

Adèle returned to France in 1804 and managed to get her parents’ names erased from the list of proscribed émigrés, so they were able to join her in the following year. “I have always liked taking part in politics as an amateur,” she wrote later, and before long she was feeling very much at home in Paris, had made friends with opposition figures such as Madame Récamier and Germaine de Staël, and had established a largely political salon, frequented by a number of diplomats, including Count Tolstoy, Count Nesselrode, and Count Metternich. She writes, “I saw many members of every party, and was agreeable to them all. My opinions were known, but were not expressed with bitterness.” This political interest, fed day by day, was to be a leading feature of her life.

On the subject of Napoleon she long remained undecided. She admired him vastly as a reformer, sympathized wholeheartedly with his pragmatism and contempt for “idealists,” and compared him favorably with the miserable Bourbons—those brothers of Louis XVI, the Comte de Provence and the Comte d’Artois, who would later rule France as Louis XVIII and Charles X. She was amused, but also impressed, by Napoleon’s high-speed mode of entry into a ballroom:

Advertisement

He walked first with such speed that almost everybody, not excepting the Empress, was almost obliged to run to keep up with him. Dignity and grace were thus out of the question, but this rustling of skirts and rapid pace seemed to symbolize a dominant power which suited him. It was magnificent, though not in our way.

As the arbitrariness of his rule increased and the country grew weary of victories, she began to detest him, as most did. Nevertheless she calls his march from Cannes to Paris during the Hundred Days perhaps “the greatest personal achievement accomplished by the greatest man of modern times.”

Adèle’s father was appointed ambassador to the Kingdom of Sardinia in 1814, and thus the Hundred Days found the Osmonds in Turin, where the kingdom’s court was established. It was for Adèle, who disliked it, the quaintest, most antediluvian autocracy imaginable, the elderly king’s sole ambition being to restore the state of things as they were in “Novant-ott” (1798), i.e., before the French occupation. The French embassy was considered a seat of wickedness; it was decided to destroy the museums created by the French as works of Satan; and the only vent for deep political intrigue was the disposal of boxes at the opera house. Fortunately for Adèle, her father was then offered and accepted the ambassadorship to Great Britain, and between 1816 and 1819 the Osmonds took up residence in London.

A great subject throughout Adèle’s memoirs is the refugee and émigré mentality, which she had been so well placed to study both in England and in France. Shall we call her a historian? We would call Saint-Simon one, and her “secret histories” of court life, her grasp of a hidden chain of events, at once haphazard and logical, often remind us of him. Here is how she explains the “ultra” clericalism which in the end brought down the Bourbon monarchy. Louis XVI’s brother the Comte d’Artois, at one point, had to take refuge from his creditors in Holyrood Palace, in Edinburgh. There was a price to pay for this in that Scottish Catholics were zealous in taking him off to Mass in their private chapels, the services sometimes lasting five or six hours. Artois being more or less of a freethinker, this bored him dreadfully; so he decided to employ his own personal priest; and, on the advice of his mistress, Mme. de Polastron, he engaged a certain Abbé Latil, said to be a humble fellow who could be expected to take his meals with the servants.

Mme. de Polastron, however, was deeply impressed when, her cousin the Duchesse de Guiche being on her deathbed, Latil took charge of the situation, bringing about her conversion and only allowing her lover into her room on condition of his sharing in this conversion. Unknown to Artois, Mme. de Polastron thereupon entrusted her own heart and conscience to the abbé. She was ill herself and, after Artois brought her to London, she began to have extravagant fancies, said to be a symptom of consumption. They proved very expensive, so Artois’s major-domo devised a scheme to pay for them. It was to announce an imminent royalist rising in the Vendée or Brittany and secure some thousands of pounds from the British government to support it. “Two or three hundred were given to some poor wretch who went to meet his death on the coast,” writes Adèle, “and the rest was swallowed up by the caprices of Mme. de Polastron…. The émigrés in England were accustomed to regard English money as their legitimate prey to be secured by any means.”

Mme. de Polastron’s health gradually sank. She became too exhausted to talk, so the devoted Artois would read religious books to her; then this task was taken over by Latil, who added his own pietistic commentaries; and at the moment of her death, Mme. de Polastron took Artois’s hand and, placing it in Latil’s, said, “My dear Abbé, here he is: I give him to you, take care of him.” Latil did not lose a moment. He carried Artois off to a church, where he made him confess and kept him for several hours:

From that moment, his influence was such that with a mere glance at the Prince, he could make him change his conversation.

Latil went on to become archbishop of Rheims and a duke.

Mme. de Boigne is intensely quotable. Her tone, very often, is sardonic, and she has a gift for an unexpected flick of irony. Thus, concerning Talleyrand’s wife: “The remains of her great beauty adorned her stupidity with a fair amount of dignity.” On the subject of Chateaubriand she is more elaborately malicious, though it must be said sometimes very funny. Finding himself left out of the Martignac ministry formed in January 1828,

M. de Chateaubriand was so furious that he nearly choked with rage: it was necessary to place leeches round his neck, and others on his temples when these proved inadequate. The next day his bile had gone into the blood, and he was as green as a lizard.

Her character studies, especially of the royal household, are long-meditated, developing from volume to volume, and are often surprisingly tolerant.6 She was, moreover, very capable of self-criticism. She speaks of her shame at her own “dreadful feeling of delight” when, during the Hundred Days, she learned of the condemnation of the Comte de Labédoyère for his betrayal of the city of Grenoble by turning it over to Napoleon—a hideous example, as she told herself, of “partisan passion.”

In a way the most fulfilled part of Adèle’s long life (she died in 1866 at the age of eighty-five) came in its last thirty years, when she became the close friend and crony of Baron (later Duke) Pasquier (1767–1862), sometime minister of the interior, president of the Chamber of Peers, and, from 1837, chancellor of France. They would write to each other every morning, about events of the day, and he would join her salon each evening—or in summer they might stay at her country mansion at Chatenay. He was an “indispensable” of the political scene, under any régime, and she thought him infinitely knowledgeable.

Adèle, as the French title indicates, had thought of her book as addressed to her nephew, Rainulphe d’Osmond. However, falling out bitterly with Rainulphe, she disinherited him and, instead, left her manuscript to his son Osmond d’Osmond. Osmond, who came into the inheritance in 1881, was not a very literary person, so it was agreed that a close friend of his, a historian named Charles Nicoullaud, should edit the memoirs. However, as Nicoullaud says in his introduction, they felt scared to bring them out at once, there being “too many private interests and personal rights to be considered,” not to mention political dangers—for royalist and clerical passions were running high in these decades of the secularization of French education and the Dreyfus affair. Accordingly, they agreed to postpone publication for twenty-five years. This, in effect, muffled the impact of the book.

All the same, Nicoullaud and Osmond had reason to be nervous. In 1909, in his book Belles du vieux temps, the Vicomte de Reiset, an ardent legitimist, published a blistering attack on Mme. de Boigne and her Memoirs. “Her intelligence and penetration are incontestable,” he wrote, “but what is even more incontestable is her partiality and injustice, her total lack of good faith. She is a ‘plague,’ knowingly and deliberately mischievous.”7 What particularly galled Reiset was her account of the Duchesse de Berry, mother of the Bourbon “Pretender” the Comte de Chambord; and indeed Mme. de Boigne’s portrait of the Duchess, who nearly precipitated a civil war in 1832, is one of her most absorbing and satirical.

Bibliographically speaking, the Memoirs and their translation present some puzzles. The French original of 1907– 1908 was, as we saw, published in four volumes and took the story up to and beyond the Revolution of 1848. Rather surprisingly Heinemann published an excellent translation of the first three volumes in the very same years, 1907– 1908, taking the story to 1830; they did not, however, publish the translation of the concluding volume until 1912 (under the title Recollections of a Great Lady: Being More Memoirs of the Comtesse de Boigne). Moreover, they failed all along to give the name of the translator, or even to mention the book’s being a translation. Also, to confuse matters further, a “Publisher’s Note” said that “their [the Memoirs‘] existence has been referred to in innumerable memoirs published during the latter part of last century.” Given Nicoullaud’s anxious protectiveness over the manuscript, this must certainly be untrue.

We seem to have here the explanation of a serious weakness in the new two-volume abridged version edited by Anka Muhlstein, i.e., that it stops—for no good reason so far as one can see—at 1830, though Mme. de Boigne had many striking things to say about the ensuing July monarchy and its fall. Apart from this, the new abridgment has a lot to recommend it. The abridging itself is very tactfully and sensitively done, though it entails leaving out the two fascinating opening chapters and dropping many of Mme. de Boigne’s longer anecdotes and novella-like stories. This seems perfectly reasonable, though it is not a matter of cutting out dead wood, for really there is none. The discreet Nicoullaud disguised certain names with an “X” or a “Z” or a dash and also replaced a few embarrassing phrases and sentences by dots, but both were spelled out fully in subsequent French editions. Muhlstein has thus been able to fill in the missing names, though she does not reinstate the passages concealed by dots. She cuts most of Nicoullaud’s copious notes but provides a very helpful “Dictionary of Characters.” Her edition forms a physically very pretty book, with a charming and inventive use of civilité type.

“The most careful reader of Mme. de Boigne’s Memoirs was Marcel Proust,” writes Muhlstein in her introduction. Far from it. It is true that Proust published an article about the Memoirs in Le Figaro of March 20, 1907, but I get a strong impression that he hardly read a word of them. It was a brilliant article—much of it, to his rage, cut by the editor, though luckily the manuscript has survived.8 It argued the fantastic thesis that in “the immense catacombs of the past,” nothing is ever lost. (As one might put it, time is not “lost” but merely mislaid.) This leads him on to a dissertation, close to a passage in his novel, about the “bluff” by which an author of memoirs can make it appear that her salon was the last word in fashionable brilliance, when in fact it was a second-rate affair, boycotted by the truly elegant. This indeed, he argues, is what drives such women to write, and it is true of almost all this class of memoirists, except perhaps Mme. de Boigne (my italics). He goes on to speak of memoir-writers who “often have a long liaison with an elderly statesman, who comes to talk politics with her every evening.” This, evidently, is the seed of Mme. de Villeparisis’s liaison with Monsieur de Norpois in Proust’s novel. But Proust knew about Adèle’s friendship with Pasquier from Sainte-Beuve, who wrote about the chancellor several times. (Proust speaks with extreme admiration of a letter Adèle wrote to Sainte-Beuve at the time of Pasquier’s death.) No one who has actually read Adèle’s Memoirs could possibly class them, as he might seem to, as “charming frivolous recollections”—nor in fact, as I have shown, does he. Not reading them proved quite as fruitful for him as reading them.

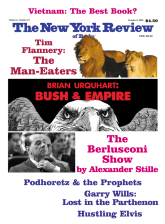

This Issue

October 9, 2003

-

1

A great-grandfather of Adèle’s was tutor to the Old Pretender.

↩ -

2

The Palais Royal was the headquarters of the Orléans family, a junior branch of the Bourbons, descended from Louis XIV’s brother.

↩ -

3

See Henry Bordeaux, Le Comte de Boigne (Paris: Hachette, 1956), chapters 14 and 15.

↩ -

4

See Françoise Wagener, La Comtesse de Boigne (Paris: Flammarion, 1997), p. 90.

↩ -

5

Mémoires du Général Baron Thiébault, edited by Fernand Calmettes (Paris: Plon, 1894), Vol. 3, pp. 538–539.

↩ -

6

Though Charles Nicoullaud, the original editor of the memoirs, admits in his introduction that, when she has to speak of unworldly and saintly souls, “her judgments are formulated in such language that it has been necessary to soften them.”

↩ -

7

Marie Antoine, Vicomte de Reiset, Belles du vieux temps (Paris: Émile Paul, 1909), p. 261.

↩ -

8

See Proust’s Contre Sainte-Beuve, edited by Pierre Clarac and D’Yves Sandre (Paris: Bibliothèque de la Pléiade, 1971), pp. 924–929, where the omitted portion is printed.

↩