1.

In Jhumpa Lahiri’s first novel, a Bengali immigrant in America called Ashoke Ganguli is a fan of Gogol. When he was a student in India, his grandfather had told him to “read all the Russians, and then reread them.” Ashoke was particularly held by “The Overcoat,” the story of Akaky Aka-kyevich, a poor, much-trampled-upon petty clerk, who grows obsessed with a new overcoat, which he thinks would bring him dignity, and which, just after he has acquired it, is stolen from him. The character reminded Ashoke of his father, who had been a humble clerk in Calcutta. He broke down every time he read about the clerk’s humiliation and death. And the more he read, the more “elusive and profound” the story grew. “Just as Akaky’s ghost haunted the final pages, so did it haunt a place deep in Ashoke’s soul, shedding light on all that was irrational, all that was inevitable about the world.”

Much later in his life, when he is a professor of engineering in America, Ashoke quotes Dostoevsky to his uncomprehending, slightly resentful teen-age son, whom he has named after Gogol, and to whom he presents a volume of stories by the Russian writer. “Do you know what Dostoevsky once said?… We all came out of Gogol’s overcoat.” Gogol, saddled with a name he thinks he shares with no one in the world, is not impressed. “What’s that supposed to mean?” he asks before putting the book away, unread, on a “high shelf between two volumes of the Hardy Boys.”*

He doesn’t read “The Overcoat” even when it is prescribed in his high school English class, for he believes that “it would mean paying tribute to his namesake.” His American classmates have a different objection to the story. They find it “too long” and “hard to get through.” It seems that there is little they can relate to in the account of a drab, rather inarticulate man in nineteenth-century Russia sliding to his doom over the small matter of an overcoat.

A hundred and fifty years ago, the protagonist of Poor People (1846), the first novel by Dostoevsky, had no problem relating to “The Overcoat.” In fact, he found it uncomfortably close to his own experience. Like Akaky Akakyevich, he is a lowly clerk, and suspects that the story mockingly describes his own attempts to live an honorable life:

You hide sometimes, you hide, you conceal yourself inside whatever you’ve got, you are afraid at times to poke your nose out—because out of everything that could be found on earth, out of everything they’ll make you a satire, and then the whole of your civic and family life goes around in literature, everything is printed, read, mocked, gossiped about! And then you won’t even be able to show yourself in the street; I mean, it’s all so well demonstrated here, that now you can recognise the likes of us just by the way we walk.

Dostoevsky was still paying such backhanded tributes to his great precursor in a later novel, The Idiot. He was never less than aware that Gogol had first put a very ordinary person, “protected by no one, dear to no one, interesting to no one,” in the landscape of Russian fiction, and thereby made real whole lives and worlds that existed almost out of sight in Russia.

This achievement, for which the literary critic Belinsky praised Gogol and the early Dostoevsky, belongs these days to writers emerging out of the immigrant communities of Europe and America. It chiefly distinguishes the first novel by the Dhaka-born British writer Monica Ali, Brick Lane, which is named after a street in London’s East End that is known primarily for restaurants that offer mostly North Indian food and are more often than not run by Bangladeshis. Its main characters, like those of Jhumpa Lahiri, are Bengalis. But, unlike Ashoke Ganguli and his family, Chanu and Nazneen are Muslims from Bangladesh, and they belong to the lower, rather than middle, class, leading lives in contemporary London that seem no less covert and full of yearning than those of the petty officials of nineteenth-century St. Petersburg:

He started every new job with a freshly spruced suit and a growing collection of pens. His face shone with hope…. He worked hard for respect but he could not find it. There was in the world a great shortage of respect and Chanu was among the famished.

Much of the novel is told from the point of view of Chanu’s wife, Nazneen, who as a young woman surrenders herself to fate in the way her mother wants her to (“If God wanted us to ask questions, he would have made us men”). Only eighteen years old, she leaves Gauripur, her village in Bangladesh, after her arranged marriage to the forty-year-old Chanu, and travels to a wholly unknown and largely bewildering country.

Advertisement

The realist novel, a product of the European bourgeoisie, usually depends for its effect on a heightened consciousness of individuality, or on the struggle against fate that Nazneen’s mother thinks is futile. Ali set herself a difficult task in choosing as her main protagonist someone whose English consists of three words, “sorry” and “thank you,” and who, confined mostly to her small flat, knows no one apart from a handful of Bengali women.

In the early pages, which describe Nazneen’s arrival in a London of graffiti- and drug-ravaged housing developments, Ali compensates for the plainness of her character’s inner life with sharp perceptions of her dreary physical world and of the weird white people who live in it:

The women had strange hair. It puffed up around their heads, pumped up like a snake’s hood. They pressed their lips together and narrowed their eyes as though they were angry at something they had heard, or at the wind for messing their hair.

She is bemused, too, by her husband, Chanu, his obsession with promotion in his minor job with the London city council, his rants against the English people he describes as “ignorant types,” his readings in history and literature, his certificates in philosophy, and his authorship of a short story titled “A Prince among Peasants.”

She looked at him for a long time…. His eyes, small and beleaguered beneath those thick brows, were anxious or faraway, or both.

Nazneen is pursued by memories of the life she has left behind: of walking through the paddy fields with her sister, Hasina, of rain falling as she dresses her mother’s corpse for her funeral. “It beat down on the tin roof, it hit the ground and bounced jubilantly up, it hurled fat globs through the doorway.” She tries to suppress her panic and boredom through regular prayer and readings in the Koran. However, she seems more engaged by ice-skating on television:

While she sat, she was no longer a collection of the hopes, random thoughts, petty anxieties, and selfish wants that made her, but was whole and pure.

It is late in her time in London—fifteen years after her arrival, long after the death of her first child (powerfully evoked by Ali), when her two daughters are in their early teens—that she begins to step out of her insular world. And it may be that faced with the void of these uneventful years, no more bearable in fiction than in actuality, Monica Ali decided to give Nazneen’s sister, Hasina, who lives in Bangladesh, a large presence in the novel. Ali uses the old-fashioned device of letter-writing to present Hasina’s experience of life in Bangladesh; it helps her cover rapidly the long years during which Nazneen raises her two daughters, and move to the novel’s denouement in 2001.

Hasina rebelled early against her fate, but her choices have not worked out well. She elopes with a young man who turns out to be unstable and violent. She works at a garment factory in Dhaka, and is raped by an elderly benefactor, before being forced by poverty into prostitution. Her story may sound a bit too action-packed and lurid, but then life in places like Dhaka still tends to melodramatic brutality of the sort that began to fade out of European literary fiction in the nineteenth century.

Still, the effort to render a commonplace third-world atrocity in an European art form tells on Ali’s prose, which, suitably plain for the most part, struggles to find the correct register in Hasina’s letters, wavering, among other things, between the Trinidadian patois familiar to us from V.S. Naipaul’s early fiction (“she respectable like hell living in London and everything”) and an abrupt poetic ambition (“Mattress hold me like lover”). Then, at times, Hasina sounds more like a travel writer from England than an oppressed Bangladeshi woman, especially when she reports on the rickshaws in Dhaka painted with the face of Britney Spears.

Although Hasina’s letters expand almost unmanageably the scope of the novel, they also allow Monica Ali to highlight an irony. The woman in Bangladesh who rebels against her fate ends up longing for the security of convention. “Sister I know how you enjoy to leave your flat,” she writes after her second, more stable, marriage, “But I have come inside now. How I love the walls keep me here.” Nazneen herself is not sure whether the greater options of self-refashioning available, at least in the abstract, in the society she lives in necessarily lead to happiness:

In Gowipur, a sweetmaker was a sweetmaker, a shoemaker was a shoemaker, and a carpenter was a carpenter. They did not want to be teachers or librarians. They were not waiting for promotions. They did not make themselves unhappy.

As it turns out, Ali doesn’t much dramatize these contrasting visions of human fulfillment. She seems more interested in making Nazneen undergo the sentimental education of characters in European and American novels. After Nazneen leaves her almost wholly secluded life she begins an affair with a younger Muslim called Karim. Ali describes sensitively the growth of physical attraction between Nazneen and Karim, and the racial politics of the East End—the stand-off between English Islamophobes and increasingly radicalized Muslim youth—that draws them closer together. However, as the relationship progresses, and Chanu continues to flounder, it is hard not to feel that as the housewife driven by boredom to illicit romance, Nazneen is a victim of Bovaryism, doomed to ineffectual remorse and, perhaps, suicide.

Advertisement

As the novel ends, it is surprising to see her emerging confidently from her affair. She discovers Karim is immature and drops him. She dances to pop music in her room and goes ice-skating. Her transformation seems a bit abrupt when she refuses to join Chanu in his endeavor to begin a new life in Ban-gladesh, preferring to be a single mother in London.

After denouncing Gogol for exposing his private life in “The Overcoat,” the protagonist of Dostoevsky’s Poor People concedes that “it would have been all right if towards the end he had at least improved, toned things down….” Ali succeeds brilliantly in presenting the besieged humanity of people living hard, little-known lives on the margins of a rich, self-absorbed society. But in the end, Ali’s empathy for disadvantaged Muslim women like Nazneen seems to have made her endow her fictional character with a will greater than what the reader of her novel has come to expect.

It is her husband, Chanu, who emerges as a fuller character in his unrelieved failure. This pompous man who refers to his wife as a “good worker” and beats his daughters even while exhorting them to read Tagore grows throughout the novel under Nazneen’s gaze, which is alternately diffident, skeptical, caustic, and affectionate. Frustrated in his professional ambitions by what he suspects is racism, he tries to assert his intellectual and moral superiority over his surroundings:

You see, they feel so threatened. … Because our own culture is so strong. And what is their culture? Television, pub, throwing darts, kicking a ball.

Things would be better for his daughters, who have grown up in a more self-consciously multicultural England. But Chanu, the first-generation immigrant, cannot avoid a sense of futility:

You see, all my life I have struggled. And for what? What good has it done? I have finished with all that now, I just take the money. I say thank you. I count it…. You see, when the English went to our country, they did not go to stay. They went to make money, and the money they made, they took it out of the country. They never left home. Mentally. Just taking money out. And that is what I am doing now. What else can you do?

2.

Traveling from India to Massachusetts in the 1960s, Ashoke and Ashima Ganguli, the Bengali couple in Jhumpa Lahiri’s The Namesake, have fewer causes of resentment. It is a bit cold, and Calcutta seems agonizingly far. But Ashoke is a middle-class professional, part of the Indian community that within two decades would become the richest ethnic minority in America. He lives with his wife, son, and daughter in a two-story house in a university town near Boston. The family possess a barbecue, roast turkey at Thanksgiving, celebrate Christmas, and “appear no different from their neighbors.”

Nevertheless, from the time she arrives from Calcutta, Ashoke’s wife, Ashima, feels that “being a foreigner is a sort of lifelong pregnancy—a perpetual wait, a constant burden, a continuous feeling out of sorts.” Like the English in India, and Chanu in London, the Gangulis have never quite left home. It is the fate of their son Gogol to live, as a second-generation immigrant, in America, without the comforting fantasy of returning to India. In prose that is as graceful as it is vivid, Lahiri charts his peculiarly solitary growth into adulthood and the confusing legacy of a mixed culture:

For their rest of his life he will remember that cold, overcast spring, digging in the dirt, collecting rocks, discovering black and yellow salamanders beneath an overturned slab of slate. He will remember the sounds of the other children in the neighborhood, laughing and pedaling their Big Wheels down the road. He will remember the warm, bright summer’s day when the topsoil was poured from the back of a truck, and stepping onto the sun deck a few weeks later with both of his parents to see thin blades of grass emerge from the bald black lawn.

As an adolescent, Gogol is not particularly rebellious, except about his name, which he changes to “Nikhil.” His exasperation with his old-fashioned parents, who continue to call him Gogol, is tinged with affection. He refuses to read his namesake; but then he doesn’t seem to read much.

In fact, he appears rather passive, even more so than Nazneen, as he goes through the motions prescribed by his East Coast, Indian-American background: success at high school is followed by Yale and Columbia, and then a career as an architect in New York, an apparently unexacting progression which is accompanied by some obligatory pot-smoking and dating and Bob Dylan and Nietzsche.

As a successful and good-looking Indian-American in New York, he awakens swiftly to the variety of pleasures he is entitled to: sex, good food, wine, arty cinema. He is helped in this self-discovery by white American women, particularly Maxine Ratliff, the daughter of a rich and stylish couple called Gerald and Lydia, who, with their five-story townhouse in Chelsea, interests in Antonioni and I, Claudius, and polite curiosity about Hindu fundamentalism, seem to have emerged out of the fantasies of advertisers in The New Yorker.

The Ratliffs have a lakeside house in New Hampshire, to which Nikhil travels with Maxine one summer. On the way, he visits his aging parents. Lahiri describes this awkward meeting with the same susceptibility to mood and alertness to the smallest tremor of feeling that marked her short-story collection, The Interpreter of Maladies. The Indian food at lunch is “too rich for the weather.” The chairs are “uncomfortab[ly] high-backed” and the seats “upholstered in gold velvet.” Nikhil becomes “overly aware” that his parents “are not used to passing things around the table, or to chewing food with their mouths fully closed.” He notices that “they avert their eyes when Maxine accidentally leans over to run her hand through his hair.” He knows that his parents will not open or enjoy the gift pack Maxine bought at Dean and DeLuca.

Eager to move away from his Indian ancestry, Nikhil is aware of how Maxine has “the gift of accepting her life” and that “she has never wished she were anyone other than herself raised in any other place, in any other way.” In New Hampshire, he wonders about the bare, even joyless, life his parents have known:

They would not want to go hiking, as he and Maxine and Gerald and Lydia do almost every day, up the rocky mountain trails, to watch the sun set over the valley. They would not care to cook with the fresh basil that grows rampant in Gerald’s garden or to spend a whole day boiling blueberries for jam. His mother would not put on a bathing suit or swim. He feels no nostalgia for the vacations he’s spent with his family, and he realizes now they were never really true vacations at all. Instead they were overwhelming, disorienting expeditions, either going to Calcutta, or sightseeing in places they did not belong to and intended never to see again.

Later, while Nikhil is feasting in Chinatown on “flowering chives and salted squid and the clams in black bean sauce that Maxine loved best,” his father, who is temporarily working alone in Cleveland, has a heart attack. Lahiri evokes movingly the desolation of Ashoke’s death in midwinter Ohio, and the suppressed grief of his family in a house overcrowded with mourners. She names no emotion, but by patiently accumulating details and scenes—the bleakness of the dead man’s apartment, an old memory of a walk with him on the beach—makes us inhabit Nikhil’s guilt-ridden state of mind. He seems to be acting perfectly in accordance with it when he breaks off his relationship with Maxine, and starts going out with, and eventually marries, Moushumi, a Bengali woman recommended to him by his mother.

Lahiri’s delicately omniscient irony is unlikely to let Nikhil settle blandly into a semi-arranged marriage with a fellow Bengali. As it turns out, his wife, Moushumi, a graduate of Brown University and a doctoral student of French literature at NYU, has aspirations to a bohemian-academic style. Soon Nikhil is attending with Moushumi and her academic friends

an endless stream of dinner parties, cocktail parties, occasional after-eleven parties with dancing and drugs to remind them that they are still young, followed by Sunday brunches full of unlimited Bloody Marys and overpriced eggs.

Nikhil and Moushumi move to an apartment in the Twenties, off Third Avenue. “They spend a few weekends taking the shuttle bus to Ikea and filling up the rooms: imitation Noguchi lamps, a black sectional sofa, kilim and flokati carpets, a blond wood platform bed.” Their best friends are Donald, a painter, and Astrid, a teacher of film theory at the New School, a “languidly confident couple, a model, Gogol guesses, for how Moushumi would like their own lives to be.”

Forever in need of guidance, Moushumi dips into The Red and the Black before embarking on an affair with a fellow academic, a reader of The Man Without Qualities. Nikhil finds out about it; the marriage ends quickly, and, like much else in Lahiri’s fiction, quietly, its dark emotions unexpressed on the page but fully present in the reader’s mind. On the last pages of the novel, Nikhil returns to his parents’ old home in order to say goodbye to his mother, who has decided to spend half of the year in India.

At one point in his marriage, when he is beginning to feel stifled by the need to “swear by a certain bakery on Sullivan Street, a certain butcher on Mott,” Nikhil comes across an English translation of a French novel. Lahiri doesn’t reveal its title. The clues she gives—an “unhappy love story” in which the main characters have no names and are referred to as He and She—point to Georges Perec’s novel Things. Reading this ironical account, published in the 1960s, of a frantically trendy French couple enjoying the affluence of postwar France, Nikhil is relieved by the absence of names and wishes that “if only his life were so simple.”

He is beginning to find out that you don’t gain a fresh identity or a fuller life by changing the name your parents gave you. It is no consolation to him that when his mother, who is the only person who still calls him Gogol, leaves America, his break from the past will be complete:

Without people in the world to call him Gogol, no matter how long he himself lives, Gogol Ganguli will, once and for all, vanish from the lips of loved ones, and so, cease to exist. Yet the thought of this eventual demise provides no sense of victory, no solace. It provides no solace at all.

Liberation from the bonds of the old world, such as that achieved by Nazneen in Brick Lane, has left him adrift and anxious. When on the last page of The Namesake he sits in his room, “thirty-two years old, and already married and divorced,” reading Gogol at last, he knows that he does not possess the “stamina” with which his parents have lived out their lives in America.

“Read all the Russians, and then reread them. They will never fail you.” This excellent advice may be more readily followed by young writers of Asian and African background than by their American or English peers, in whose hands the novel often appears a private, whimsical form. As the examples of Brick Lane and The Namesake prove, writers trying to describe the people who lie smudged behind such journalistic labels as “underdeveloped” “third world,” and “Islamic fundamentalism” often begin where the Russian writers so beloved of Nikhil’s grandfather and father began: with the small, poignant dreams of ordinary people.

But what happens when those dreams are realized, or, as in Brick Lane, partially fulfilled? Nazneen becomes a person by rejecting the authority of her past and by following the desires that she feels in her new world. However, the hopeful ending her creator contrives for the novel through an adulterous affair and ice-skating doesn’t stop one from thinking that a more arduous life for Nazneen is just about to begin, in which she would know, sooner or later, that to become an independent person in the modern world does not necessarily mean escaping the roles other people have set out for you.

This is the melancholy awareness that suffuses Lahiri’s catalogs of desirable things and people. And so while such obvious underdogs as Nazneen and Chanu arouse pity and indignation, an overprivileged immigrant like Ni-khil leaves one with more disturbing feelings: an intimation, such as the one his father once had, of “all that was irrational, all that was inevitable about the world”; a suspicion that “all men are mild lunatics engaged in pursuits that seem to them very important while an absurdly logical force keeps them at their futile jobs.” It is as if we have been given a glimpse not so much of an unjust social or political setup as of what Nabokov, writing about “The Overcoat,” called “flaws in the texture of life itself.”

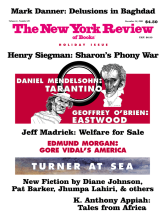

This Issue

December 18, 2003

-

*

Cheap and easily available Soviet translations meant that educated Indians in previous decades often knew Gogol and Dostoevsky better than they knew Flaubert and Henry James, and some of them in the Communist-dominated states of Kerala and West Bengal even named their children after their favorite authors: a large number of Gogols, and, more disconcertingly, Lenins and Stalins, exist in India today.

↩