To the Editors:

Russell Baker, in his commentary on The Great Unraveling by Paul Krugman [NYR, November 6], has, no doubt, touched all the bases, while at the same time he has managed to raise quite a few serious questions on the constraints journalists face, as well as the limits they have to put upon themselves, because of their own monetary considerations. Point in question is the failure of journalists, especially those working for the video media, to expose the great economic chicanery perpetrated by Mr. Bush—with an expressed view of stimulating economic growth—by cutting taxes, that benefited mostly those who could afford to pay not less, but a little more. This, Mr. Baker suggests, was because these TV stars that work as newscasters are in the upper bracket of wage earners; that made them also the beneficiaries in this legislation.

I wonder whether job security had played any part in the silence of the journalists on this matter. Yes, we know, Mr. Baker will claim that the journalists are intrepid in pursuit of discharging their duties, which are to uphold the rights of the people to know the truth, and to maintain their journalistic freedom.

To prove my point, I am citing the following examples. We all know the philosophies of the O’Reillys and Limbaughs. Though they go on spewing venom against the Democrats, most notably against the liberals, I wonder if anyone with a liberal bent will be allowed to speak in the same vein, and can still hope to keep his job. It is also surprising that Mr. Novak, after outing a CIA agent, can still carry on what he does best, that is, to bash the liberals. The journalistic courtesy accorded to him by his peers is mind-boggling.

Or let us take the case of Mr. Daniel Schorr. He was not seen on CBS since the day he had a run-in with Mr. Helms, the then CIA director. After Garry Trudeau, in his cartoon, made an unflattering comment about Bush Sr.’s manhood, his wife Jane Pauley became a casualty, perhaps, as she was removed from The Today Show by the NBC network. Connie Chung was, similarly, perhaps, dropped as a co-anchor on the CBS Evening News, after she had revealed that the mother of Newt Gingrich had called Mrs. Clinton a bitch. These may be just conjectures; but they are too obvious to be dismissed as coincidences.

Most of the media in our country are the possessions of big conglomerates. Surely, these corporations are in the market, just like all others, with the same goal, which is to earn a good profit on their investments. Could it be that journalistic freedom plays a secondary role to earning a profit? Or, for that matter, could job security be also playing a significant part in modifying the opinions of the journalists? Thank God, because of journalists like Mr. Krugman, who also happens to have a day job at one of the prestigious universities, like Princeton, we know when to call a spade a spade.

Mohammad A. Meah, MD

Paramus, New Jersey

Russell Baker replies:

Dr. Meah is right about the journalist’s job-security problems, but something more fundamental than household economics may be reshaping journalistic attitudes toward public issues. Today’s top-drawer Washington newspeople are part of a highly educated, upper-middle-class elite; they belong to the culture for which the American political system works exceedingly well. Which is to say, they are, in the pure sense of the word, extremely conservative.

Most probably passed childhood in economically sheltered times, came to adulthood in the years of plenty, went to good colleges where they developed conventionally progressive social consciences, and have now inherited the comforting benefits that sixty years of liberal government have created for the middle class.

This is not a background likely to produce angry reporters and aggressive editors. If few made much fuss about President Bush’s granting boons to those already rolling in money, their silence may not have been because they feared the vengeance of bosses, but only because the capacity for outrage had been bred out of them. Belonging to the upper-middle-class elite may do that.

The accelerating collapse of the American health care system may illustrate how journalism’s disconnection from the masses will produce an inert state. If every journalist in the District of Columbia had to have his health insurance canceled as a requirement for practicing journalism in Washington, quite a few might refuse to flee, but stay on, get to know what anger is, and discover that something is catastrophically wrong with the health care system.

This is no more likely to happen than Congress and presidents are likely to be stripped of their government-financed health and hospital care after the insurance industry takes over the remainder of the health industry.

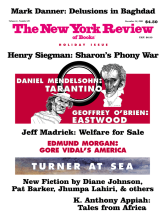

This Issue

December 18, 2003