“Reade him, therefore; and againe, and againe.”1

1.

In 1811, Charles Lamb published his subtle and pugnacious essay “On the Tragedies of Shakspeare, considered with reference to their fitness for stage representation.” In it he argued not that Shakespeare’s tragedies should never be acted, but that they are made “another thing” by being acted. “Nine parts in ten” of what Hamlet does are “the effusions of his solitary musings, which he retires to holes and corners and the most sequestered parts of the palace to pour forth.” How, Lamb asks, “can they be represented by a gesticulating actor, who comes and mouths them out before an audience, making four hundred people his confidants at once?”2 And again:

To see Lear acted,—to see an old man tottering about the stage with a walking-stick, turned out of doors by his daughters in a rainy night, has nothing but what is painful and disgusting. We want to take him into shelter and relieve him. That is all the feeling which the acting of Lear ever produced in me. But the Lear of Shakspeare cannot be acted.

The contemptible stage machinery for imitating the storm falls as far short of the horrors of the real elements as any actor’s attempt to portray Lear:

They might more easily propose to personate the Satan of Milton upon a stage, or one of Michael Angelo’s terrible figures…. On the stage we see nothing but corporal infirmities and weakness, the impotence of rage; while we read it, we see not Lear, but we are Lear,—we are in his mind, we are sustained by a grandeur which baffles the malice of daughters and storms; in the aberrations of his reason, we discover a mighty irregular power of reasoning….

Goethe expressed a similar opinion, four years after Lamb, in his “Shakespeare and no End.” “Shakespeare’s fame and excellence,” Goethe tells us, “belong to the history of poetry. It is a mistake to suppose that his whole merits lie in his importance in the history of drama.” And again:

Shakespeare gets his effect by means of the living word, and it is for this reason that we should hear him read, for then the attention is not distracted either by a too adequate or by a too inadequate stage-setting. There is no higher or purer pleasure than to sit with closed eyes and hear a naturally expressive voice recite, not declaim, a play of Shakespeare’s.

Reading, in other words, whether we do it ourselves, or get a nonhistrionic friend to do it for us—reading and imagination are the keys to the essential Shakespeare.

The opposite view became well entrenched by the end of the twentieth century. No longer was it an open question whether certain of Shakespeare’s plays were performable: all were performable in principle, and all were indeed, with varying degrees of frequency, performed. Performance itself became the criterion for interpretation: “We must allow Shakespeare himself to decide what must be studied. Throw out those learned introductions to the text. We are to learn by doing, and the insights of actors are more likely to be right than those of scholars.”3 “A play has to be seen and heard in order to be understood.”4 “The stage expanding before an audience is the source of all valid discovery.”5

This seems to derive from a stage-struck scholarship, or from a critical orthodoxy that conveniently forgets how much a modern production of Shakespeare depends on scholarly and critical guidance. Actors are taught by directors, and directors are taught at universities. And if they happen not to be, it remains true that without scholarly editions neither actor nor director would have the foggiest notion of what crucial passages in the plays mean.

Shakespeare, we are told by Stanley Wells in his new book, Shakespeare for All Time, prepared none of his works, except the narrative poems, for publication:

He was above all a man of the theatre, writing scripts for performance, not for reading. Only about half of his plays appeared in print during his lifetime, in the flimsy little paperback form of the quarto, and there is no sign that he had anything to do with their publication.

The quartos were considered ephemeral. “Sir Thomas Bodley, founder of the Bodleian Library in Oxford, deliberately excluded plays from his collections….” The language of Shakespeare’s plays “needs to be apprehended as poetry and prose meant not to be read but to be heard in a theatre.” And on the same page the point is driven home that

reading plays calls for a kind of imaginative activity quite different from that required by the reading of lyric or epic poetry, or novels and discursive prose. Shakespeare’s prose and verse need to be judged by the standards of drama, not literature.

Wells is an important and prolific Shakespeare scholar, here addressing a popular audience but elsewhere keen to preach the same doctrine. In 1986 he and Gary Taylor published the Oxford edition of Shakespeare, which provides the textual basis for the Norton edition and is thus widely used. (This is the edition that tried to persuade us to call, for instance, Henry VI Part Two “The First Part of the Contention of the Two Famous Houses of York and Lancaster.”) In the textual companion to this work, Taylor tells us that “Shakespeare intended his words to be acted: to be heard, not read. Shakespeare’s plays thus stand midway between Homeric epic (orally composed to be aurally apprehended) and modern novels (written to be read).”6

Advertisement

At the very least, there is more conjecture behind such statements than their certainty of tone would suggest. For just as we do not possess any tape recordings of the oral Homeric epic, but only manuscripts handed down by very long literary tradition, so we do not possess any authorial manuscript of a Shakespeare play, but rely on contemporary printed versions in quarto, for some of them, and the posthumous “First Folio” for the rest of the dramatic corpus. We rely on texts printed to be read for an argument that insists that Shakespeare did not write plays to be read.

Shakespeare died in 1616, and the First Folio was published in 1623, under the supervision of two of Shakespeare’s friends and fellow actors. It has proved exceptionally authoritative in one matter at least: by general scholarly agreement, no one has successfully added a whole Shakespeare play to its canon, and no one has removed one either. Wells himself says: “We don’t know when the Folio was first planned, but my guess is that Shakespeare discussed it with his colleagues during his last years.”

The notion that Shakespeare, in common with other dramatic poets of the day (Ben Jonson excepted), had no thought for posterity and was unconcerned with the circulation of his dramatic works through print asks us to believe first of all that quarto publication was ephemeral and beneath serious consideration. Sir Thomas Bodley, as already mentioned, is sometimes quoted as excluding such “riff raff Books” from his library: “I can see no good Reason, to alter my Opinion, for excluding such Books, as Almanacks, Plays, and an infinite Number, that are daily Printed, of very unworthy matters.” We have already seen Wells referring to the “flimsy little paperback form of the quarto” (although of course the distinction between paperback and hardback belongs to the modern era). But according to Lukas Erne, Bodley may have been exceptional in his fastidiousness. Now comes a work which challenges everything that Wells has been saying on this subject. In Shakespeare as Literary Dramatist, Erne, who teaches in Ge-neva, argues that Shakespeare, in addition to being a playwright who wrote theatrical texts for the stage, was also a self-consciously literary dramatist, producing reading texts for the page.”

Erne cites numerous counterexamples against Bodley. For instance Sir John Harington, the translator of Ariosto, who died in 1612, “purchased, bound and catalogued the great majority of all the playbooks published in the first decade of the seventeenth century, including no fewer than eighteen copies of Shakespeare’s plays.” Sir Edward Dering “recorded the purchase of no fewer than 225 playbooks in the years 1619 to 1624.” The poet William Drummond of Hawthornden, in the year 1606, read forty-two books, eight of which were plays.

Indeed, I find that Drummond expressed the opposite view to Bodley’s when, in his short essay “Of Libraries,” he wrote:

Libraries are as Forrests, in which not only tall Cedars and Oaks are to be found, but Bushes too and dwarfish Shrubs; and as in Apothecaries Shops all sorts of Drugs are permitted to be, so may all sort of Books be in a Library: And as they out of Vipers and Scorpions, and poisoning Vegetables, extract often wholesome Medicaments, for the Life of Mankind; so out of whatsoever Book, good Instructions and Examples may be acquired.7

The selection of “good Instructions and Examples” from Shakespeare’s plays is not some sentimental Victorian aberration. It began midway in his career. Erne prints a passage from Romeo and Juliet, anthologized in 1600 in a book called England’s Parnassus, or, The choycest flowers of our moderne poets:

Care keepes his watch in euery olde mans eye,

And where Care lodges, sleepe will neuer lie:

But where vnbruiz’d youth with vnstuft braine

Doth couch his limbs, there golden sleepe doth raine.

(It means that worrying keeps the old awake, while the young sleep soundly.) Shakespeare had ninety-five such passages in this anthology, many fewer than Edmund Spenser (386), Michael Drayton (225), William Warner (171), and Samuel Daniel (140), but not bad going for a poet supposedly unconcerned with posterity.

Advertisement

Two years before, Francis Meres had singled out six poets for special praise in his Palladis Tamia: Sir Philip Sidney and the aforementioned Spenser, Dan- iel, Drayton, Warner, and Shakespeare. Palladis Tamia is the famously boring (but not in this respect stupid) book that refers to Shakespeare’s “sugared Sonnets among his private friends” and calls the poet “our best for Tragedy.” Indeed, Wells quotes Meres thus: “As Plautus and Seneca are accounted the best for comedy and tragedy among the Latins, so Shakespeare among the English is the most excellent in both kinds for the stage.” Those who hold that this is not evidence of a literary reputation for Shakespeare are also obliged (as I see it) to add that it is not evidence for the literary reputation of Plautus and Seneca either.

At the same time, in 1598, four quarto editions were brought out with Shakespeare’s name on the title page. In the previous year both Richard II and Richard III had been published anonymously in quarto, as was the common practice. Now suddenly (for the second editions of both of these) it was worth putting a name to the text.

2.

Erne’s argument that Shakespeare’s plays were supposed to be read is made up of a multitude of details such as this, drawn largely from bibliography and, on their own, dry enough. But the case as it builds up is exceedingly interesting and, to a nonspecialist, convincing. Early on Erne points out that no fewer than twenty-eight of the sonnets deal prominently with the theme of poetry as the immortalization of the person in them. He cites J.B. Leishman writing in 1961:

So far as I am aware, no writer on the Sonnets has remarked upon that fact that [Shakespeare], who is commonly supposed to have been indifferent to literary fame and perhaps only dimly aware of the magnitude of his own poetic genius, has written both more copiously and more memorably on this topic [i.e., poetry as immortalization] than any other sonneteer.

Leishman goes on:

It seems to be generally assumed, in a vague sort of way, that most, perhaps all, sonneteers, English, French and Italian, perhaps even from Petrarch onwards, had written a great deal about their own poetry, and that Shakespeare was merely saying the sort of things they had said, but saying them better: this…is far from the truth.

I must admit that I had made exactly that assumption. More plausible is a Shakespeare with a strong sense of his ability to confer immortality through his poetry.

A Shakespeare, indeed, with a sense of his own merit—a figure more like Ben Jonson, who incurred mockery by publishing his collected works in folio. It is a part of our conception of the indifference of Shakespeare to his fame that we contrast it with Jonson’s perceived egotism, but Shakespeare resembles Jonson in at least one related respect: he wrote some plays that, although they are known to have been performed, seem rather too long for stage performance uncut. Very long, in the case of Jonson’s Bartholomew Fair, which would take more than five hours to perform. In Shakespeare’s case, Richard III (3,570 lines), Hamlet (3,537), Troilus and Cressida (3,323), and Coriolanus (3,279) are among the longest. Three thousand lines is a long play by the standards of the time. According to one calculation, there are 233 plays extant that were acted on the public stage in London between 1590 and 1616. Of these, twenty-nine are longer than three thousand lines. Of these twenty-nine long plays, only seven were not written by either Jonson or Shakespeare.

The phrase from Romeo and Juliet, “the two-hours’ traffic of our stage,” appears not to be a casual expression. Many other authors use its equivalent, and even if it is a stock expression, rather than an accurate standard performance length, there is evidence—mustered by Erne—to show that somewhere between two and three hours was what the Elizabethan audience expected or could take. Many of them, the groundlings, were standing. There was in the open-air theaters no stage lighting. The performances began in the afternoon, and must have ended by dusk. They “begin at two,” says one source, and “have done between four and five.” None of Shakespeare’s comedies presents a problem in this respect. It is the histories and tragedies that tend to be long.

Erne argues that these long plays were written both for the stage and for the page. Shakespeare knew they would be cut in performance, but the option was opening up, during the course of his stage career, to give the plays a double life. A note by John Marston to the second edition of Parasitaster, or The Fawn, draws an interesting distinction: “Comedies,” says Marston, “are writ to be spoken, not read: Remember the life of these things consists in action; and for your such courteous survey of my pen, I will present a Tragedy to you which shall boldly abide the most curious perusall.” He is excusing the shortcomings of a comedy when seen on the page, and at the same time promising the publication of a tragedy, Sophonisba, which he expects to survive the attention of the reader.

John Webster’s Duchess of Malfi was announced on its title page as “with diverse things Printed, that the length of the Play would not bear in the Presentment.” He apparently makes a distinction between the text as performed, which he calls the “Play,” and the “Poem,” which is his work alone, and which, as Erne puts it, “lives on in print in order to be read.” The address to the readers in the folio of Beaumont and Fletcher tells us that when these comedies and tragedies were presented on stage, the actors omitted some scenes and passages, with the author’s consent. When “private friends” asked for a copy, a transcription was made of what had been acted. But now, the passage continues, “you have both All that was Acted, and all that was not; even the perfect full Originalls without the least mutilation.”

The sense, then, that there might be an original script of a play, which represented the poet’s fullest intentions, is not the product of anachronistic thinking. Among the manuscripts of a play that might have been floating around when the First Folio was prepared, there might be the author’s original full script, the version as acted, and the acting version as copied (with full permission) for some person for his private enjoyment. The gap between performance and first printing in quarto might be accounted for as a period in which there was money or some other advantage to be gained by making these private transcriptions. The quarto was not, in Erne’s view, something that undermined the interests of the acting company: a quarto might indeed, by its publication, give publicity to the revival of a play.

The best way (in my opinion) for the modern reader to get a feeling for a Shakespeare tragedy as it was performed is to think of Macbeth: surprisingly short at just over two thousand lines, but even so with some odd material that is usually cut today, it seems to derive from an acting text, while the original could well have been a third as long again. Meanwhile we are allowed, once again, to do what Lamb and Goethe recommended, and what Heminge and Condell, Shakespeare’s close friends, asked us to do: to read him again and again. No doubt Erne’s book will in due course come under attack, or at least receive the reply it deserves from those whose propaganda it criticizes. It may seem crazy that a man has to sit down and write an exceedingly learned book to prove that Shakespeare is literature. But I must say I found this mustered evidence and these arguments completely gripping.

3.

Fintan O’Toole, theater critic and excellent biographer of Sheridan, first published his “Radical Guide to Shakespearean Tragedy” in 1990 under the title No More Heroes. The audience aimed at is young, and the tone adopted can be engaging: somewhat angry, contemptuous of those he considers enemies, often funny. He is violently opposed to the attempt to link Shakespearean tragedy to anything deriving from Aristotle. But listen to this:

Even the word “tragedy” itself is something that was forced on to Shakespeare’s plays long after they were written. The Stationers’ Register, which recorded the titles of his plays in Shakespeare’s own time, lists Hamlet as a “revenge,” King Lear as a “history,” Antony and Cleopatra as “a book called Antony and Cleopatra.” Othello is listed as a tragedy, but then so are Richard II and Richard III, which we now call “history plays.”

Students who rely on this passage may find themselves in trouble. The division of Shakespeare’s plays into comedies, tragedies, and histories was systematized in the First Folio, not “long after they were written.” On their “catalogue” page, Heminge and Condell list eleven tragedies. Eight of these, in Wells and Taylor’s “original titles” (in the edition O’Toole is using), feature the word “tragedy,” and the exceptions are not particularly interesting. And why, by the way, are young students being asked to pay such attention to the Stationers’ Register? Is it really such an illuminating document in the matter of genre?

It is right to warn students against using Aristotle as a guide to Shakespeare, quite misleading to say that Shakespeare “certainly knew that he was not writing the most respected and highbrow kind of tragedy of his day, the one which followed classical (mostly Roman) models.” Shakespeare was a classicizing author, and we have already seen him compared by one contemporary to Plautus and Seneca. Jonson in his tribute invokes the names of Aeschylus, Euripides, and Sophocles, to their disadvantage.

In 1963, in an anthology called Shakespeare’s Tragedies, Laurence Lerner printed a little text that he called “The Elizabethan View of Tragedy,” but which on closer inspection turned out to be an extract from a late Roman commentary on Terence, attributed to one Evanthius. Here it is:

Among the many differences between tragedy and comedy, the following is the principal one: that in comedy the characters are of moderate estate, the passions and dangers are mild, the outcome of the action is happy; but exactly the opposite is true of tragedy: the characters are great, the dangers severe, the conclusion sad. Furthermore, in comedy things are upset at the beginning and peaceful at the close, in tragedy things take place in the reverse order. Tragedies express the view that life should be rejected, comedies that it should be embraced. Finally, the events of comedy are always fictitious, those of tragedy are often true and taken from history.

Lerner did not claim this as a perfect fit for Elizabethan drama, but it is suggestive. In particular, the idea that tragedies are often taken from history chimes well with the (otherwise surprising) fact that, as O’Toole notes, Richard II and Richard III were originally published as tragedies. The two versions of Lear Wells and Taylor printed in the Oxford edition are respectively labeled History and Tragedy. The distinction would not have been important to Evanthius, and might not have mattered much to Shakespeare either, at certain points in his career. But it is perfectly possible that, if Shakespeare had a hand in the planning of the First Folio, the division of his dramatic oeuvre into comedy, history, and tragedy is his: looking back on the drama he had written, he saw it could be conveniently, if not ideally, distinguished in this way.

O’Toole is very keen to attack A.C. Bradley, whose Shakespearean Tragedy is still apparently (or was still in 1990) the bane of Irish classrooms. I say: fine. If Bradley is getting between Shakespeare and Irish youth, go for him by all means: tear him limb from limb. I notice, however, the following passage in Lawrence Danson’s Shakespeare’s Dramatic Genres. Danson points out how much Bradley excludes from his definition of Shakespearean tragedy:

Romeo and Juliet may be a “pure tragedy” but it is “an immature one”; Richard III, Richard II, Julius Caesar, Antony and Cleopatra, and Coriolanus “are tragic histories or historical tragedies,” which owe too much to their sources “to be judged by the standards of pure tragedy”; Titus Andronicus lacks Shakespeare’s “characteristic tragic conception,” and much of Timon of Athens should (Bradley thinks) “be attributed to some other writer.” We are left with Hamlet, Othello, King Lear and Macbeth. Bradley did not invent this distinction between the Big Four and all the rest, but he gave it an authority which still shapes, or distorts, our notion of Shakespearian tragedy as a whole.8

O’Toole, after his introductory section, devotes one chapter each to Hamlet, Othello, King Lear, and Macbeth. To this extent he turns out to be a crypto-Bradleian.

The most modest contributions to the definition of English tragedy may at the outset be the most helpful to the student. English tragedy, like Spanish drama of the same period, mixes high and low, comic and serious. Unlike the Spanish, however, it does not tell biblical stories. Nor is it written with actresses in mind. It favors variety of action, and can accommodate extended time-schemes. It is not dependent on scenery or the elaborate effects associated with masks. It is not Aristotelian. It may mix verse and prose. Fighting and killing may take place on stage (indeed, fencing is an important part of the English classic actor’s skill).

The characteristics of Shakespearean theater can be overt and unmistakable. If you went to a Russian opera house and saw Boris Godunov played, and you had no Russian and no knowledge of the piece, you would nevertheless be able to detect the influence of Shakespeare on the drama. You would see that there was a monarch of some kind, and that there was a beggar or fool, some sort of destitute figure who seemed to have important things to say. You would get a sense of the passing of time, of a shifting of scene, of high life and low life, of the domestic apartment of some kind of palace as well as perhaps a council chamber, of quarrels among noblemen. The clues would be overt.9

Why it happened that English and Spanish tragedy both characteristically mix serious and comic material must have something to do with the kind of theaters in which they performed. Frank Kermode, in The Age of Shakespeare, his admirable short introduction to the whole subject, reminds us that

if the Globe ever had a full house and an attendance of three thousand, it is a safe bet that around 2,700 of them were not scholars, not the kind of auditors Gabriel Harvey had in mind when he remarked that Hamlet was a play to “please the wiser sort.” It had to please others not warranting that description. Consequently the respect for classical antecedents—Ovid, Seneca, Plautus—had to be consistent with the telling of a good story; and the dramatists, valuing their freedom as well as their obligation, ignored these august precedents whenever they felt it advisable to do so. So a play that is based upon a tragic story, and begins tragically, may have a happy ending (The Winter’s Tale, for instance), and English writers wrote tragicomedy without consulting elaborate Italian theories about that genre.

The few things that Kermode says about genre in this book (it is not a question which overworries him) are always interesting:

Cymbeline and The Winter’s Tale can reasonably be called tragicomedies, although insofar as there were prescriptions for tragicomedy Shakespeare violated the one that says that in this genre characters are brought near to death but do not die; for Cloten dies in Cymbeline and Mamillius in The Winter’s Tale. Cymbeline was included among the tragedies in the Folio of 1623. Nomenclature is a minor problem.

My emphasis. Yes, indeed, nomenclature is a minor problem, but the fact that ambiguities can arise, that Troilus and Cressida can be described variously as tragedy or comedy or history, is one of the characteristics of the English drama of the time.

Kermode’s book comes in the series of short introductory books called Modern Library Chronicles. It is more personal than an encyclopedia article, but not so polemical as to forget the interests and the rights of the reader who really is turning to this subject for the first time, or who wants up-to-date guidance. Kermode devotes some time and sympathetic consideration to a theory he nevertheless does not believe in: that Shakespeare in the “Lost Years” was working as a teacher in Lancashire in recusant (Catholic) circles—indeed, that he may have been a Catholic himself. The caution displayed here is of particular interest, since Kermode’s other researches have made him alive to biblical and theological questions, and the religious background of the period receives some attention.

I don’t see much about the sonnets; but Kermode tentatively suggests that Shakespeare’s original motive in coming to London might have been, as a poet, to seek a patron, “having somehow got wind of one.” On this view, he drifts into play writing in the way that modern poets and novelists drift into book reviewing. Kermode’s Shakespeare never retires—he spends more time in Stratford, but he does not necessarily leave London. Among the fascinating facts, we learn that

Charles I took a copy of the Second Folio into captivity—it is now in the library of Windsor Castle—and altered the titles of the plays to suit his preferences, so that Twelfth Night is renamed “Malvolio,” and Much Ado about Nothing became “Benedick and Beatrice.” The wit combats of these characters were apparently what pleased most.

John Gross, in his anthology After Shakespeare, tells us that Charles’s love of plays was cited by his enemies as evidence of his depravity: “Had he but studied Scripture half so much as Ben Jonson or Shakespeare…” is the Puritan line, in a sentence that ends, presumably, “we wouldn’t have had to chop his head off.” Gross quotes a “positively sinister gloss” put by Milton on Charles’s love of Shakespeare. Milton wrote a pamphlet called Eikonoklastes, replying to the King’s Eikon Basilike (meaning “royal image”; it contained meditations purportedly by him):

I shall not instance an abstruse author, wherein the King might be less conversant, but one whom we well know was the closet companion of these his solitudes, William Shakespeare; who introduces the person of Richard the Third, speaking in as high a strain of piety, and mortification, as is uttered in any passage in this book [Eikon Basilike]; and sometimes to the same sense and purpose with some words in this place. “I intended,” saith he, “not only to oblige my friends but mine enemies.” The like saith Richard, Act 2, Scene I:

I do not know that Englishman alive

With whom my soul is any jot at odds

More than the infant that is born tonight;

I thank my God for my humility.Other stuff of this sort may be read throughout the whole tragedy….

Milton seeks, by verbal parallels, to turn Charles I into a tyrant counterfeiting religion, like Shakespeare’s Richard. Recalling Milton’s tribute to Shakespeare in the Second Folio, which he also prints, Gross comments that this is “a far cry from ‘What needs my Shakespeare for his honoured bones’ or the ‘sweetest Shakespeare fancy’s child’ of L’Allegro.” True: Milton comes across here as a particularly dangerous sort of hypocrite. Gross’s anthology is full of interesting and unusual material such as this. It is learned, ludic, and likable.

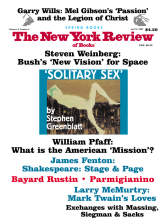

This Issue

April 8, 2004

-

1

John Heminge and Henry Condell’s address “To the Great Variety of Readers,” in the First Folio, 1623.

↩ -

2

Abridged versions of Lamb’s and Goethe’s essays are printed in Jonathan Bate’s useful collection The Romantics on Shakespeare (Penguin, 1992).

↩ -

3

J.L. Styan, Perspectives on Shakespeare in Performance (Peter Lang, 2000), p. 17.

↩ -

4

John Russell Brown, William Shakespeare: Writing for Performance (St. Martin’s, 1996), p. viii.

↩ -

5

Styan quoted by Lukas Erne, Shakespeare as Literary Dramatist, p. 22. Erne says that Styan is paraphrasing and agreeing with John Russell Brown.

↩ -

6

Stanley Wells and Gary Taylor with John Jowett and William Montgomery, William Shakespeare: A Textual Companion (Oxford University Press, 1987), p. 3.

↩ -

7

The Works of William Drummond of Hawthornden (Edinburgh, 1711) p. 223.

↩ -

8

Lawrence Danson, Shakespeare’s Dramatic Genres (Oxford University Press, 2000), p. 115.

↩ -

9

With good reason. Pushkin, who wrote the play on which the opera is based, consciously emulated Shakespeare. He wrote that he was “firmly convinced that the popular rules of Shakespearian drama are better suited to our stage than the courtly habits of the tragedies of Racine and that any unsuccessful experiment can slow down the reformation of our stage.” See Pushkin on Literature, translated and edited by Tatiana Wolff (London: Methuen, 1971), p. 248.

↩